Archive

How Harvest Rains Destroy Coffee Crops

Harvest time in El Salvador is November to February/March. It’s a cool, dry season perfect for the picking of coffee cherries. Yet this year it’s already been marked by heavy rains.

While in El Salvador for the first PDG Micro Coffee Festival, we saw rainfall strike suddenly and dramatically. Coffee flowers were opening on the trees even as pickers were harvesting cherries – something you might expect to see in Colombia, but not El Salvador. Carlos Pola of Finca Las Brisas told me, “It’s like snow in June. It never rains at this time of year.”

This isn’t just a freak weather phenomenon. This is a serious concern for many producers, who face decreased income this year and an irregular harvest next year.

A Rainy Harvest Means Damaged Coffee

While rain is important for growing high yields of well-developed coffee, it poses a threat for ripe cherries. They may fall from the ground, where if left too long they will begin fermenting.

In other cases, the cherries may stay on the branch but start cracking. This happens when a lot of water is quickly absorbed and so the cells in ripe cherry peel are forced apart. The sweet mucilage seeps out of the cracks, resulting in a lower weight and a worse cup score. “It loses all its honey,” Rafael Silva of SICAFE explained.

On a night visit to Cuatro M processing mill as part of the Micro Coffee Festival, we saw how coffee cherries are graded based on ripeness. The ideal lot has many ripe red cherries, few over-ripe ones, few pink ones, and no under-ripe ones. “Tomorrow, we’ll pick pink because of the rain,” Roberto, the General Manager, told me. “It’s a risk, waiting for the cherries to become ripe.”

Picking pink will mean a lower cup score and price. But waiting to pick red risks losing large portions of the harvest or seeing a lower cup score. It’s a lose-lose situation.

Issues at the Mill

Rain doesn’t just cause problems on the farm. It’s also an issue at the mill. Rafael explained that, for recently picked coffees, it’s okay if they get a little wet – but that for those that are nearly at the right moisture level to be bagged and exported, it can have a serious impact. “You need to dry them again,” he said. “It needs a second processing. That causes quality issues.”

Even if you only have freshly picked coffees drying on your patio, heavy rain can still cause problems. “You need to put wood between the lots, or they can mix,” Rafael told me. “Then you cover them. But when it comes down this fast… ” He gestures at the rain around us. “Then you don’t have time to do that.”

The rain’s sudden appearance is one of its most damaging aspects. Even those with coffee in GrainPro channels, designed to protect the beans from rain, stood to suffer: at Micro Coffee Festival, they didn’t have time to close the bags before significant amounts of water had already drenched them.

“This is the peak time for mills right now,” Rodrigo Silva of SICAFE said. “And so it’s the hardest time to deal with rain.”

The Financial Impact on Coffee Producers

Those processing natural and honey coffees are the worst hit, along with smallholder farmers with less staff, resources, and financial breathing space.

Rafael and Rodrigo told me that rains like this can see cupping scores decrease by a few points or more. The market price for coffee is approx. $1.30-1.35/lb right now; specialty is $2.50-3.00/lb. Specialty coffee cups at 80 points or higher, but many roasters will only purchase single origins that are 84+. The difference between a 79 and an 82, or an 82 and an 85, is costly.

And smallholder farmers in particular may be left with no choice but to watch their coffee depreciate in quality. “We have to call our mills to have them separate and cover coffee,” Rafael told me. “And to move nearly ready cherries inside the greenhouse… [But] smaller farmers just have to pick up all their cherries the very next thing.”

Issues Extending Into Next Year

“Next year, we’ll be harvesting in August.”

It’s a comment I heard multiple times during Micro Coffee Festival El Salvador. Heavy rains caused coffee flowers to appear on the branches early – but the appearance of flowers is linked to the development of cherries. While it varies, depending on variety and location, Arabica cherries typically appear nine months after the appearance of the coffee flower.

With the high probability of this year’s crop being both lower quality and lower yield, some low-income farmers might appreciate an earlier harvest next year. It may help stave off the “thin months”, that period before the harvest when money for food has run out.

But an early harvest will impact on supply and demand, as Salvadoran coffees compete with those that normally appear in August – such as Peruvians, Brazilians, and Kenyans. Less demand and more supply means lower prices and so those thin months might last even longer.

Typically, an early harvest could also lead to a shortage of pickers, as it is seasonal work. However, since coffee leaf rust (la roya) hit hard in 2012, affecting yield as well as quality, there has been a surplus of coffee pickers – one producer estimated there to be 25% more pickers than is needed.

Even this silver lining merely cloaks a nasty reality, however: if the harvest starts early, it will probably end early. Pickers who normally hope to work until February or even March may find themselves out of a job come December. And the gap between the 2017 and 2018 harvest will be wider, meaning the length of those thin months is likely to increase.

A Blind Specialty Industry?

Rodrigo Silva of SICAFE told me, “Genuine buyers don’t get to see these problems. When they come to the farms, it’s not rainy season. And so they have no idea of the problems a simple rain can bring.”

Only twenty minutes earlier, Jesús Salazar of Cafeólogo discussed the reasons why some coffee producers may prefer to work with local “coyotes” than with specialty buyers. One of the reasons is that there’s less risk: if it rains, the coyote will still buy the coffee.

There is no easy answer to the problem of harvest rains. The specialty industry must continue to care about quality – but we cannot ignore the welfare of the producers and farm workers to do so. We need to ask ourselves what more we can do to provide income stability, not just when the weather is good, but also when rain, wind, or disease destroys crops.

Paying higher prices, aiding producers in purchasing equipment to keep coffee dry, offering loans against future crops… No method will solve the issue of harvest rains, but there are many ways we can attempt to support producers in the face of inconsistent weather conditions.

A Coffee Producer’s Guide to Soil Management & Farm Conditions

Our coffee can only be as good as the land that it’s grown on – but by my calculations, nearly 35% of coffee crops are produced in the wrong environmental conditions.

I’m talking about something called life zone, which refers to the temperature, luminosity/solar brilliance, rainfall, relative humidity, and soil characteristics that are best suited to coffee farming.

As an agronomist, allow me to take you through the ideal life zone for growing coffee – and what poor conditions will mean for your harvests.

The Ideal Coffee-Growing Conditions

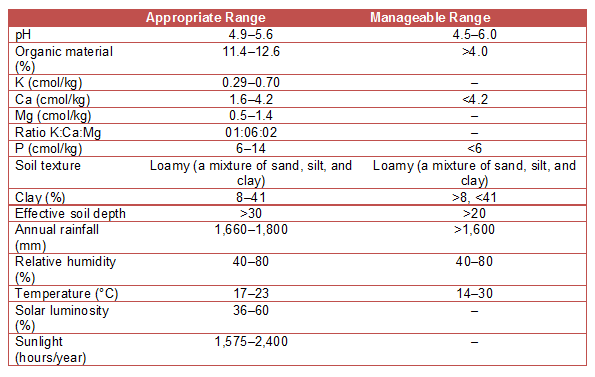

According to Dr. Gloria Gauggel, the ideal life zone for Arabica coffee is as follows:

Let’s break down some of these qualities in a little more detail.

Effective Soil Depth

When it comes to your soil, you need to consider both its structure (which includes the soil texture) and chemistry (essential elements and minerals).

These two factors are connected because of the coffee tree’s root structure. As the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) explains, each tree will have multiple types of roots. The tap roots will grow down deep. However, there are also many secondary roots.

The secondary roots lie within the top 30 cm of soil and their role is to recover water and nutrients from the soil. As of such, the essential elements are key – and a loamy soil of the right pH ensures that the coffee tree can absorb the nutrients well.

Essential Elements & Minerals

The coffee tree requires 16 essential elements for its proper nutrition. These can be divided into four groups, based on their function and importance.

Group 1: Carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen. These elements are present in water and air, which is why the life zone is so important.

Group 2: Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. These are also called “macronutrients,” due to the large amount of them that healthy coffee trees need.

Group 3: Calcium, magnesium, and sulphur. These are called “secondary elements,” because they are needed in lesser amounts than the macronutrients.

Group 4: Zinc, boron, manganese, molybdenum, iron, copper, and chlorine. These are called “microelements,” because even less of them is required – although they are still essential for coffee plant nutrition.

The importance of all these factors is visible in the plant’s harvest. Growing coffee in an adequate life zone reduces costs, makes work easier, and increases yield. In turn, this lowers risk levels and makes coffee production more financially sustainable.

For this reason, it’s important that producers plant coffee within an adequate life zone. Of course, within this life zone, there will still be variation in terms of soil conditions, hours of sunlight, rainfall, and more. These will require producers to adapt their farm management further (ideally with the assistance of an agronomist).

35% of Coffee Grown in The Wrong Life Zone

From an analysis of these factors, I have calculated that nearly 35% of the world’s coffee crops are outside the adequate life zone. During the past 10 years, I’ve visited 16 coffee-producing countries across three continents (America, Asia, and Africa). On these trips, I’ve worked on farm management, project development with small and medium-sized producers, and crop research.

That research involves the analysis of 22 aspects of coffee farming, ranging from the agronomical and environmental to the economic. My team analyzes one hectare per thousand hectares of coffee plantations in each country. We take as a reference the thermal zones and compare them to the physiological behavior of coffee trees, based on temperature and rainfall as the most relevant indicators.

From here, we reached the conclusion that 35% of coffee crops are planted outside the adequate life zone. Of that 35%, 30% are completely outside the ideal life zone. The remaining 5% are where farms are mostly within the ideal life zone but the producers have extended their plantation outside of it.

So what does it mean for producers if a farm is outside of the ideal life zone? Let’s take a look.

Growing Coffee in Poor Conditions

If a farm is in an upper marginal zone, i.e. it exceeds the figures in the table, you can expect:

- Slower tree growth

- Lower productivity

- A lower fruit yield with higher weight and density

- Higher susceptibility to diseases

- In the wet season, a higher risk of disease and pests

- Better sensory qualities for the coffee

- Increased production costs compared to crops within the adequate life zone

And if it’s in a lower marginal zone?

- More aggressive tree growth

- Higher productivity

- Lower yield made up of low-density fruit

- Higher susceptibility to pests and diseases

- In drought seasons, a high risk of losing all or some of the plantation and/or harvest

- Reduced sensory qualities

- Increased production costs compared to crops within the adequate life zone

Of course, you should remember that you may also see these traits on farms in the adequate life zone if there are problems with the farm management. Healthy coffee plants are a result of many factors, including farming practices, life zone, and more.

It’s important that we consider the ideal farm location and soil condition for coffee production. Planting in the right zones can help producing families to realize greater profit margins on their crops. It can also stabilize climate conditions as the local ecosystem will be more balanced.

For producers, there’s so much more to consider than just the farm location and soil condition: asset management, financial restructuring, varieties, processing methods, laborers… But the life zone is an important starting point.

How Field Mapping Can Increase Profitability For Coffee Producers

How can you achieve both higher productivity and improved quality on your coffee farm? By using field mapping. The method can help you better understand your land, improve yield and quality, and create an opportunity to match both your specialty and commodity coffee to its correct market.

Take a look at what field mapping is, how it works, and what is preventing it from being more widely used.

What Is Field Mapping?

Field mapping is agricultural data analysis. By gathering and analysing data about your coffee crops, you can introduce more precise management plans, monitor quality, and potentially increase yield. The coffee can then be sold as either commodity or specialty grade to the relevant market.

In simple terms, field mapping allows you to match the right coffee to the right part of your land and understand what it needs to thrive.

Through data analysis, you can mark lots with high potential for additional investment of resources. Lots with lower potential may receive lower investment, in line with their predicted profitability. After harvesting and processing, each lot is sold to its appropriate market.

By using methods such as soil analysis and visual data, field mapping can save producers time, effort, and money.

Why Use Field Mapping?

In 2016, the global coffee yield average was 17 bags per hectare. This varied wildly from 42 bags per hectare in Vietnam, 23 bags per hectare in Brazil, to 8 bags per hectare in Ethiopia. The ICO attributed this variation to poor farming practices. It stated that “less than 10% of smallholders in Africa use crop protection or fertilisers, and most tend not to utilise basic agronomic techniques”.

At the fourth World Coffee Conference, in 2016, Geraldine Joselyn Fraser-Moleketi, presenting as the Special Envoy on Gender of the African Development Bank, stated “we must support farmers to achieve higher coffee productivity and improved quality through better farm management practices”.

These better farm management practices include field mapping. Let’s look at the practical benefits, some real-life examples, and what field mapping involves.

Field Mapping Means Better Quality

Fazenda Santa Jucy is a farm in São Paulo state, Brazil that produces Arabica. The director, Alexandre Provencio, tells me that he introduced field mapping four years ago. He says that before doing so, the farm management plans on Santa Jucy were limited, with up to 20 hectares of land used to grow one variety of coffee.

After analysing the soil and cupping and classifying each crop, he found that “a field of about 20 hectares [had] about four different types of characteristics”. Each of these characteristics changed the way the same variety of coffee grew.

Armed with his new knowledge about the land, Alexandre split this 20 hectares into smaller lots based on the different characteristics. He has since been able to better direct his resources. Rather than applying fertiliser to all 20 hectares, he can use it only on the specific lots that need it. This reduces costs and allows each lot of coffee to thrive.

Matching Coffee to Its Correct Market

Alexandre tells me that the same site has the potential to produce exceptional specialty coffee, specialty coffee, and commodity coffee. The challenge at Santa Jucy, he says, is to keep the specialty percentages high. To achieve this, lots with potential to produce specialty grade coffee are treated differently to those predicted to produce commodity grade coffee.

It’s a skilful way to manage a farm. Rather than investing time and money into trying to get specialty grade coffee from all of a large lot, why not determine where it makes sense to focus on specialty and where lends itself to commodity grade coffee? And then treat each lot according to its final market.

Through soil testing, you can determine the best variety of coffee for each area of your farm and pinpoint where to use fertilisers. Rather than viewing commodity and specialty as better or worse than one another, think of it as matching the land to its best coffee and then that coffee to the right market. Ideally, the two crops should support one another. Alexandre even says that you that “you cannot have specialty without commodity”.

Without field mapping, the coffee from all 20 hectares of Alexandre’s field might have been sold as commodity grade, despite having areas of specialty grade coffee. Field mapping can help you to better understand your land and coffee, and to more accurately predict profits.

How Field Mapping Works

Field mapping can be split into two areas of data analysis: agronomic and visual. The most common form of agronomic field mapping is soil analysis.

Let’s look at a concrete example. Nitrogen is necessary for healthy crop growth, but too much nitrogen in the later stages of growth can reduce the final size of the cherry. With soil analysis, you can check the nitrogen levels in your land and treat the soil accordingly. The final cherries will be larger, and the crop more profitable. Field mapping takes soil analysis a step further – rather than looking at soil quality in one area, it is the idea of looking at how soil varies across your farm and identifying how to best use each lot.

Manuel Ramos is the coordinator of the One by One sustainability programme in Guatemala. The initiative teaches smallholder farmers how to field map. He tells me that One by One teaches farmers to measure pH levels and nutrients in the soil, and then group their crops according to their deficiencies. Producers can then apply the right type and amount of fertiliser to the right lot.

For larger farms, visual field mapping through GIS technology can be more effective. Jarvis Technologies uses GIS and drone technology to analyse crops on large coffee farms. The company’s CEO, Luis Gomez, tells me that this technology is able to produce high-resolution images, GIS-interactive maps, and 3D models of farms.

Luis says that it can take one or two months to manually map a farm, but that with GIS and drone technology, 100 hectares can be captured within 30 minutes. Results can be delivered to producers within a day or two.

This quick turnaround is essential for preventing the spread of visible diseases. Leaf rust, for example, can spread across a farm in as little as 15 days. With GIS mapping, you can see the exact coordinates of affected areas and know precisely where to apply fungicides.

The Costs and Practicalities of Field Mapping

Although field mapping is useful for both smallholders and large-scale farmers, and can be applied to both commodity and specialty crops, its use is limited by expense. At present, there is a lack of affordable technology designed for smallholder farmers and access to technology is limited.

But there are affordable ways to start introducing the principles to your farm. Consider which crops grow best in which area and look into basic soil testing. By identifying nutritional deficiencies, you can choose which variety of coffee will best fit each lot of your land and where to invest more resources. You can also cup coffees from each lot and evaluate the quality to give you insight into which area suits which variety.

Field mapping can enable you to better understand your land, direct resources, and market the final coffee – whether it is commodity, specialty, or both.

Should We Pay More For Coffee?

In the current age of going green and sustainability permeating every facet of our daily routine, the coffee industry is one that has taken the mission to heart, incorporating the concept into every aspect of the supply chain, from seed to cup. But for all of its efforts, one fact that stubbornly remains is that by nature coffee is a fundamentally unsustainable product: environmentally, socially, and economically.

I often lament how little the average consumer knows about and respects the amount of work that went into that cup of coffee they so desperately need to get them through their morning. Coffee, being easily one of the most labour-intensive agricultural products in the world, is grown exclusively in developing countries, populated by a great many of the three billion people in the world living on less than $2 a day.

The economics of coffee for the producers is untenable as it is, for one simple reason — we don’t pay them enough for their product. Five dollar lattes and Fair Trade premiums notwithstanding, coffee is disturbingly inexpensive when you take a closer look at the numbers.

The cost of production of a pound of coffee is around $2.00/lb (this varies greatly country by country). Most farmers make a very small profit when they sell their coffee to the first of many middlemen that stand between them and you. When it finally gets to a café in Toronto, the cost of the beans is around $8.00/lb, which will make 30 good, strong cups of liquid coffee at about $0.27 per cup. The café has additional costs, like milk, labour, rent, etc., but a cup of black coffee still has one of the highest profit margins in the food industry.

Now, imagine for a minute that the entire coffee community could get together and agree to pay $1 more per pound, all of which was guaranteed to get into the farmers’ hands. With that cost being passed all the way through the chain to the end consumer, that now $9.00/lb coffee would raise the cost per cup by just $0.03.

Think of the good we could do when considering a few more numbers: Canadians drink just shy of three cups of coffee per day, so with the $0.03 extra per cup, that would amount to $30.66 ($0.03x3x365) out of your pocket per year. Canadians alone drink in the neighbourhood of 14 billion cups of coffee every year, so just considering our consumption here, that extra three cents could conceivably result in $420,000,000 flowing directly into the hands of those who need it most — the rural, the marginalized, those who have the least access to social programs or government assistance, and who are the most difficult to reach through development projects.

And it should be said that, while development work is crucial, the people that know the needs of third-world farmers the best are the farmers themselves, many of whom face a difficult question every year when they are paid for their crop: do I feed my family or my farm?

This idea may sound like international wealth redistribution, but really, it’s more akin to a long-overdue market correction – fixing the lopsidedness of an industry that has been built on an intensive agricultural product being treated as an easy-to-manipulate commodity. So while this dollar-more-per-pound-model is not perfect, or even feasible at the moment, it illustrates a point.

We are facing a new reality in not just the coffee industry, but the food system as we know it: the things that we consume are simply going to cost more than they have in the past. Not only because costs of production are constantly rising, but because that market correction isn’t just something that should happen… it’s something that needs to happen to fix what has become an unsustainable agricultural model.

Buying great quality coffee is one way to ensure we’re paying more for it — as with anything, growing something of great quality costs money. But quality shouldn’t be the only reason we pay more. Bad farmers don’t grow bad coffee. In fact, little if any coffee is grown by bad farmers. Some grow quantity, some grow quality, and many fall somewhere in between. While there is no doubting that a higher quality of product deserves a higher price, the average price must come up to ensure that every coffee farmer’s quality of life improves.

We need to create, or rather adapt to, a truly sustainable business model for coffee; one where the producer, consumer, and everyone in between are all financially, environmentally, and socially stable. I know I can comfortably speak for the coffee industry by saying that we’re actively working on it, every single day.

What can the average coffee drinker do to support this? There is no one answer, yet. So buy your daily cup(s) of coffee from roasters and shops that are going above and beyond for the benefit of the farmers that are producing their coffee — they’re quite easy to find with just a little bit of research. And the next time you see an infomercial that asks you if you are willing to save a child’s life for “just the cost of a cup of coffee a day,” think about just how much more good you could do by spending an extra $0.03 on your actual cup of coffee every day.

“Sustainability Looks Different Wherever You Are”: Coffee Production Practices in a Risky Landscape

The coffee sector indeed appears to be in its heyday, but what do consumption and production trends tell us of its long-term sustainability?

The annual World of Coffee event, held in early June in Berlin, Germany, is known as the largest professional conference devoted to the coffee sector in Europe, where the sheer breadth and depth of the sector can be seen in full force.

A wide range of attendees converged on Messe Hall: everyone from baristas competing for who can make the best “latte art,” to farmer organizations presenting their products and approaches to coffee cultivation, to brewing machine manufacturers exhibiting their wares.[i]

The coffee sector indeed appears to be in its heyday: coffee consumption is on the rise and is no longer concentrated in just the traditional markets of North America and Europe.[ii] The International Coffee Organization (ICO) found that global coffee consumption hit a record of over 160 million bags of coffee in 2017/18, with much of that coffee traded across national borders.[iii]

Yet the buzz around the growing demand for coffee belies some of the sector’s many challenges, which were raised by research organizations, non-profit organizations and sustainability advocates during the lecture series held within the Berlin event, as well as at the International Coffee Congress on Sustainability held the day before by the German Coffee Association in cooperation with the World of Coffee and organized by the Specialty Coffee Association.[iv]

Consumption and Demand Trends

Currently, coffee production is heavily concentrated among a select set of countries: only five countries account for nearly three quarters of overall production in 2015.[v] With consumption on the rise, the world will need at least 21 million more bags of coffee produced per year by 2031—a number that could double, or even triple, depending on growth trends.[vi]

Coffee production needs to diversify among more countries and producers to meet this demand, while ensuring that growth does not lead to severe environmental strain. This has proven difficult: despite the growth in coffee consumption, which is due largely to having greater retail options available, the production side of the sector struggles constantly with uncertainty due to years of volatile prices, along with the effects of changing weather patterns on coffee yields.[vii] Many coffee farmers, for their part, have a challenging time making ends meet, and in some cases find it too expensive to stay in the coffee sector at all. Some of these farmers, both in the world’s least-developed countries and in many emerging economies, still live in poverty.

Moving the sector toward a wider uptake of sustainable production practices in this landscape is thus a challenging but necessary task, despite the costs of investing in these practices. Speakers at two of the Berlin lectures found that there are some promising signs across different coffee-producing countries that speak to the interest in and benefits of moving in this direction.

Looking more closely at coffee production, recent figures suggest that the level of certified coffee has been on the rise in recent years.[viii] Coffee that complies with one or more voluntary sustainability standards (VSSs) can be identified by a seal or other type of labelling to denote that the product in question has undergone a process that is mindful of environmental and social impacts, as well as a rigorous VSS certification process. In the coffee sector, the main VSSs include primarily 4C, UTZ/Rainforest Alliance,[ix] Fairtrade and Organic.[x]

“Coffee is a particularly strong example of the potential for certified product,” said International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Associate Laura Turley in Berlin while presenting the inaugural Global Market Report: Coffee. The report is published by IISD’s State of Sustainability Initiatives as part of a series devoted to providing a market performance overview for key VSS-compliant agricultural commodities.[xi],[xii] “The trends that we’ve noticed in this report is that the growth of VSS-compliant coffee outpaces conventional coffee growth. In this period, from 2008–2016, conventional production is down by 8 per cent, while VSS-compliant production is up by 24 per cent,” she continued, referring to the compound annual growth rates measured over that time.

While coffee consumption is on the rise, getting consumers to pay for certified coffee rather than conventional coffee is another challenge, with the demand for certified coffee often not matching up with the growing supply. In 2016, where the latest data is available, 34.5 per cent of the coffee market overall was compliant with at least one VSS.[xiii] This share may actually be even higher: up to 21.4 per cent of the coffee market may be compliant with one of these standards, but data limitations make it difficult to know for sure.[xiv]

The production of conventional coffee does not account for environmental and social costs, and therefore neither does its price. Conventional coffee therefore appears to be cheaper to produce than certified coffee, and thus have a lower price when being sold. Given that overall price environment for coffee, most farmers will often produce coffee at prices that are actually below their production costs.

Until end consumers are willing to pay the higher price for certified coffee, farmers who choose to meet VSS requirements can find it difficult to recoup the investments they have made in meeting those standards. There are also well-documented cases of certified coffee ultimately being sold as conventional coffee, which some research suggests could be a product of end consumers not being fully aware of the label and what it means, and therefore not willing to pay the higher price.xv]

“There seems to be an oversupply of VSS-compliant coffee, which is good for end-users, but for producers this is a real challenge: we’re making this effort, we’re taking these steps, but where is the demand? Who is buying this compliant coffee?” Turley said, describing some of the challenges facing sustainable coffee production.

Growing Interest in Sustainable Practices

According to sustainability advocates, the growing demand for coffee overall will need to be matched with a boost in consumption of VSS-compliant coffee, particularly given that the supply of this certified coffee is already on the rise. If these efforts are successful, they can have important implications for the social and environmental contexts in which farmers live and work, especially in countries that are facing a suite of developmental challenges, such as biodiversity loss, income inequality and environmental degradation.

“If this trend in VSS-compliant coffee continues to grow, then maybe we should look at the potential for low human development countries (LHDCs) and not just the top growing countries,” said Steffany Bermúdez, a data collection and analysis specialist at IISD who co-authored the Global Markets Report: Coffee.[xvi]

The Global Market Report: Coffee found that LHDCs represent 11 per cent of total coffee production, but the growth in VSS-compliant coffee production in those countries has been significant. The report showed a compound annual growth rate in VSS-compliant coffee of 19 per cent in LHDCs from 2008 to 2016, much higher than the growth seen in those same countries for conventionally produced coffee.[xvii]

“We know that there are existing challenges in developing this potential [in LHDCs],” Bermúdez added. Among these challenges are the high cost of certification, the multiple certifications available, meeting the “sometimes complex criteria for VSS” and the need for “supportive services” to implement these requirements at the farm level. Boosting demand for certified coffee across the value chain is also crucial, she said, as is dealing with the existing environmental challenges that many farmers deal with.

The multiple VSS certifications mean that farmers are often juggling several costly processes at once; at the same time, the number of certifications available does speak to the private sector’s interest in VSS-compliant coffee.

“There are a lot of other companies that are playing around with having some certified coffee, companies investing in their own systems and their own sourcing and standards systems, with the idea that it’s cheaper and more efficient than adhering to the existing standards systems,” said Sjoerd Panhuysen from Hivos, a Dutch-headquartered development organization devoted to social change. Panhuysen works with Hivos’s productive landscapes program and is the lead author of the Coffee Barometer 2018.[xviii]

“What we see in the sector is a lot of double, triple and even quadruple certification,” said Panhuysen in Berlin. “There are a lot of underlying, different standards, which are aligned with Fairtrade and Rainforest, and then you get double- and triple-certified farms.” Moreover, there is clear evidence of a gap between how much standard-compliant coffee is available at the producer level, relative to the volumes procured in practice by the buyer as standard compliant. That gap is growing, though the statistics are not sufficiently clear due to problems in recording data when multiple certifications are involved. One example, he noted, is that the figures for Organic coffee are believed to overlap by some 50 to 70 per cent with coffee that is certified under the Fairtrade standard.

Research by IISD’s State of Sustainability Initiatives has also highlighted the importance of making sure that new initiatives, including industry ones, have the necessary third-party overview and the appropriate governance structures in place, with stakeholders’ involvement from the standards’ design through to their implementation and audits.[xix],[xx]

Norbert Schmitz, of 4C, noted during a separate presentation that despite these challenges, there have been signs of how producing certified coffee can boost crop yields, farmer incomes and the implementation of conservation measures. This does not ignore the fact that certification has yet to live up to its full potential, as shown by farmer incomes not matching up with the efforts they make in producing sustainably, and the costs of implementing these requirements not being compensated by the market. Poorer smallholders often cannot undergo these certification processes, and certification audits are costly and difficult.

Farmers bearing the cost and risk of trying to produce sustainably must be able to sell their products at sufficiently high prices to recoup the costs of their investments and earn a sufficient profit; in addition, these prices must be consistent enough that they can make long-term business decisions. Cooperation and collaboration across the value chain will thus be crucial in addressing those challenges, so that this clear interest in VSS-compliant production, despite the associated difficulties, is not lost.

Adapting to Different Circumstances and Sharing Risks

Looking ahead, the challenges that are involved in transitioning to more sustainable coffee production practices cannot be addressed solely in the aggregate, and sustainability, while now a common term, actually can hold varying definitions depending on the starting point of the countries and coffee producers involved.

“Sustainability looks different wherever you are,” said Miguel Zamora, Director of Market Transformation at Rainforest Alliance, in Berlin.[xxi] More specifically, the challenges that farmers face in different countries, and therefore the solutions that need to be developed, will often vary, such as when it comes to improving land ownership and labour rights regimes in their respective countries. This holds especially true for LHDCs.

“What we have found in some of the challenges to help producers to become certified is that smallholders in Ethiopia and Uganda are small in terms of the land they own,” Zamora added. “That makes it more expensive to get them to trainings, to get the investment they need to be compliant [with these sustainability standards]. […] We want to make sure producers have the chance to choose the sustainability path that brings the most value to them.”

Growing coffee is an activity that is indeed fraught with risk: the coffee sector is famous for its price volatility, for example, with prices fluctuating regularly and, at times, wildly. According to José Dauster Sette, Executive Director of the International Coffee Organization, the ICO composite indicator price shows an “almost continuous drop” since the start of 2016, and that price in January sat at 32 per cent below the 10-year average.

The implications of this price volatility are damaging both for producers and for the coffee value chain overall, Dauster Sette said in Berlin. Not only does price volatility create an economic disincentive for coffee producers, but it has also been linked to increased migration from coffee-producing countries, especially in Central America; greater social unrest; the “pauperization” of rural areas; and environmental harm, due partly to producers being increasingly concentrated in certain countries.

Climate change is also making its mark on the sector, with multiple examples already demonstrating how changing weather patterns or freak weather events can hurt coffee yields or create marked differences in coffee quality.[xxii] This risk also tends to affect farmers first, rather than being spread out across the coffee value chain.

“What we see, when we talk about risk sharing, is that there is no risk sharing: the risk is pushed toward the farm at this moment,” said Panhuysen. While some research is trying to quantify the environmental and social risks that farmers face, those risks have yet to translate into an appropriately representative “price definition.”

“A farmer actually takes a certain amount of risk going into a trajectory to become certified, which comes back every year. It comes at a cost to the farmer,” who expects these efforts to translate into a better income, Panhuysen continued. The success of these VSSs requires that all stakeholders in the coffee sector are committed to the necessary capacity-building supports and measures, as well as trade relations, to ensure that farmers and the communities in which they live ultimately see improved livelihoods as well as working, social and environmental conditions.

Private and Public Sector Actions, Options: Looking ahead

Current trends confirm that there is a need to increase coffee supply to meet demand, especially in the near term, which will require expanding production beyond the traditional countries and actors to newer participants. Whether this will require the uptake of VSSs or other approaches, and what role certification will have in this context, remains to be seen. These are important questions to consider going forward. To ensure that this supply involves sustainably produced coffee, however, it is essential to find ways to make these production methods more profitable for farmers and draw in investments. It will also involve ensuring that the coffee produced is of high quality, and that farmers have access to both alternative income sources and to high-value market segments.

To ensure that farmers have the incentive to adopt more sustainable production methods, despite their costs, also requires making sure that consumers, including end consumers, show a higher demand for sustainable, certified coffee, rather than their conventionally produced equivalent. Sustainability advocates argue that this change in consumer preferences is vital to ensuring that there is a high incentive to produce sustainably, even with the level of investments required.

Mechanisms for sharing risks will also be vital, sustainability experts say, and require actors from across the value chain to take action. Governments must adopt practices and policies that provide an enabling environment for coffee production, especially sustainable production, to thrive. Among the options that are being debated by policy-makers is establishing a minimum price, which Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire have recently announced they will do with cocoa.[xxiii] Those governments have also pledged to communicate that price information to producers, among a host of other steps to address price volatility for that sector. Governments also have a role in developing legal and regulatory frameworks that support the uptake of sustainable coffee production practices, including when it comes to improving labour and environmental laws and practices, making it easier for female farmers to obtain credit and other productive inputs, and facilitating access to markets.[xxiv]

Another option could involve finding ways to ensure that farmers can cultivate larger plots of land, potentially making it easier to reap the returns of their investments and any support they receive. Tackling costs and mapping out the impact that certification has in practice will also be key, and some promising steps have emerged in this respect, such as the use of new technologies by 4C and Rainforest Alliance to capture information about deforestation and other key metrics about supply chain traceability and sustainability. These are just a few examples; context and collaboration are key to making sure the right tools are chosen for the right situation.

Some of the steps that the private sector can take include providing better support to smallholder farmers, improving chemicals management in production and pushing for biodiversity conservation, according to Nanda Bergstein, Director of Corporate Responsibility at Tchibo, a coffee retailer headquartered in Germany that sells products such as coffee machines. Tchibo is one of the top roasters and retailers globally, as ranked by Euromonitor.[xxv] Speaking in Berlin, Bergstein also raised the point that any private sector initiative would need to cater to farmer needs, rather than what the private sector assumes their needs to be.

The private sector has a role to play in ensuring that end consumers, as in those people that buy and consume coffee as part of their daily lives, show the necessary interest in buying more sustainable products, even if it means paying a higher price. The private sector also needs to consider ways to share some of this risk so that it does not fall solely or primarily on farmers.

Ultimately, the various challenges that the coffee sector faces —price volatility, climate variations, consumer preferences—make the road to adopting more sustainable production methods difficult. However, there is a clear interest in many developing countries, and the benefits could far outweigh the costs in the medium and long terms. The growing demand from non-traditional markets provides a clear window of opportunity for expanding coffee production into newer markets, including in poorer countries that already have some share of global coffee production. This transition, however, will involve the uptake of sustainable production practices in those newer markets, which will need to be adapted to those producer countries’ particular needs. It will also require new approaches to collaboration among value chain actors that focus on supporting farmers as they adopt these practices, thus averting environmental and social harm and ensuring that they receive the necessary returns on their investments.

Looking ahead, this collaboration across value chain actors will be vital in safeguarding against risk and in ensuring that the efforts of producing sustainably can ultimately reap the desired rewards. Communication channels will need to be open and experiences and ideas must be shared regularly among industry players. This should go beyond just the major players in the industry, such as the top roasters and retailers, to include everyone from smallholder coffee producers to government officials to baristas to end consumers. Transparency along all steps of the value chain could play an important role in changing consumer preferences, so that the end consumer is ultimately aware of the benefits of certified coffee and willing to pay that higher price point, whether at the store or at their local coffee shop.

[i] World of Coffee. (2019). Home. Retrieved from https://www.worldofcoffee.org/

[ii] Voora, V., Bermúdez, S., & Larrea, C. (2019). Global market report: Coffee. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/ssi-global-market-report-coffee.pdf

[iii] International Coffee Organization (ICO). (2018, October). Record exports in coffee year 2017/2018. Coffee Market Report. Retrieved from http://www.ico.org/documents/cy2018-19/cmr-1018-e.pdf

[iv] International Coffee Congress on Sustainability (2019, June 5). Home Retrieved from https://congress-on-sustainability.com/index.php

[v] Voora et al., 2019.

[vi] ICO, 2018.

[vii] Panhuysen, S., & Pierrot, J. (2019). Coffee barometer. Retrieved from https://www.hivos.org/assets/2018/06/Coffee-Barometer-2018.pdf

[viii] Voora et al., 2019.

[ix] UTZ and Rainforest Alliance were merged in 2017 under one certification.

[x] Voora et al., 2019.

[xi] Voora et al., 2019.

[xii] State of Sustainability Initiatives. (n.d.) About SSI. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/ssi/

[xiii] Voora et al., 2019.

[xiv] Voora et al., 2019.

[xv] State of Sustainability Initiatives. (2014). Chapter 8. Coffee market. SSI Review. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/pdf/2014/ssi_2014_chapter_8.pdf

[xvi] The term “LHDC” is a category from the UN’s Human Development Index, which ranks countries based on a combination of factors, such as life expectancy, education and national income per capita.

[xvii] Voora et al., 2019.

[xviii] Panhuysen & Pierrot, 2019.

[xix] State of Sustainability Initiatives. (n.d.). Credibility: Conformity assessment. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/ssi/credibility-2/

[xx] International Institute for Sustainable Development. (2019). Voluntary sustainability standards. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/topic/voluntary-sustainability-standards

[xxi] Rainforest Alliance. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved from https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/

[xxii] Panhuysen & Pierrot, 2019.

[xxiii] Government of Ghana. (2019). Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire sign agreement on cocoa. Retrieved from http://www.ghana.gov.gh/index.php/news/4512-ghana-cote-d-ivoire-sign-agreement-on-cocoa

[xxiv] Sexsmith, K. (2019). Leveraging voluntary sustainability standards for gender equality and women’s empowerment in agriculture: A guide for development organizations based on the sustainable development goals. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/library/leveraging-voluntary-sustainability-standards-gender-equality-and-womens-empowerment

[xxv] Euromonitor. (2017). Tchibo GmbH in hot drinks. Retrieved from https://www.euromonitor.com/tchibo-gmbh-in-hot-drinks/report

By Sofia Baliño, Steffany Bermúdez on July 17, 2019

Coffee and the Countryside: Small Farmers and Sustainable Development in Las Segovias de Nicaragua

In San Juan del Río Coco, located in the Las Segovias region of northern Nicaragua, farmers have good reason to doubt the integrity of cooperative organizations. Since the electoral defeat of the Sandinista Revolution in 1989, farmers’ organizations have fought to provide access to better markets, improved productive practices, and models for democratic organization to traditionally marginalized coffee farmers in remote regions of Nicaragua’s highlands. Cooperative organization is not new to the region, but the role and focus of grower cooperatives have changed, and not for the better. Since the time of revolutionary leader Augusto Sandino in the 1930s, Las Segovias has been an area of campesino1 organizing (Macauley 1967).

During my fieldwork from 2001 to 2006, I experienced firsthand the gains and frustrations of agricultural development experienced by international development agents contracted through USAID to promote organic agricultural production in rural Nicaragua. CLUSA, the Cooperative League of the United States of America,2 penetrated remote and impoverished agrarian zones to teach organic agricultural practices to farmers who were willing to comply with its strict production, farm management, and quality standards.

All farmers make sacrifices and take huge risks in order to succeed in the coffee industry, and none more than small-scale farmers. These farmers live between bankruptcy and bonanza all year long. The facets of production that are outside the farmers’ reach, such as quality control, exportable percentages, drying, threshing, marketing, and shipping, leave farmers dependent on others whose actions they cannot control. As a result the outcomes often fall short—sometimes far short—of the farmers’ needs. This Study is an account of a remote community that struggles against a tradition of marginalization, subjugation, and deceit.

During seven years of collaboration and cooperation with small-scale coffee farmers of San Juan del Río Coco, I recognized the volatility of their economic situation. I wondered why these farmers continued to produce for an exploitative industry in support of a government that largely ignored their interests. In Las Segovias, there are no safeguards for small farmers or their families. Unforeseen illness, misfortune, or natural disasters are common causes for foreclosure. Many farmers from San Juan had sold their land to larger producers when times were tough. Many more have abandoned their parcels to seek better payment for manual labor in nearby El Salvador or Costa Rica. The risk incurred while traveling with so few resources and no insurance would be unthinkable by my North American standards.

Also, it is important to keep in mind that the Contra War between government forces and the revolutionary Sandinistas took place in this very region. I do not devote much space here to the dynamics of life and work in a former conflict zone, but the aftershocks of a war in this community had still not worn off, fifteen years after peace was settled. Impressively, among the farmers with whom I worked were both former Sandinistas, or compas, and Contra soldiers. Many of them had fought against each other in nearby arenas of battle. Because I too lost family and loved ones as a result of that war, I find it significant that these people can work to heal past wounds by supporting each other in generating productive activity, managing land, and conserving the local ecosystem.

Patrick Staib (2012) Coffee and the Countryside: Small Farmers and Sustainable Development in Las Segovias de Nicaragua

Sustainability Measurement for Small-Scale Coffee Roasters

Sustainability in Business and Agriculture

Sustainability is more than just a buzzword that businesses have latched onto for marketing appeal. Research across industries has consistently shown that a solid sustainability strategy can create value for a company’s stakeholders, help manage supply chain risk, improve employee and customer retention, and ultimately increase a company’s financial performance. In most cases, climate change is the driving force behind the concern for sustainability. In CDP’s most recent Supply Chain Report, 76 percent of the suppliers claimed that they have identified “inherent climate change risks” that could impact their profits or operations and 52 percent of suppliers have integrated climate change concerns into their business because of this (CDP, 2018). The strategic reasons to incorporate sustainability into traditional business models are clear and compelling. Business strategy aside, integrating sustainable practices can also be justified at the most basic level by the original United Nations call for sustainable development in the 1987 Brundtland Report: as a way of meeting the “needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (UN WCED, 1987).

While consideration of sustainability in supply chains is the first move in the right direction, proper sustainability assessment is the second, more crucial step towards business and global prosperity for years to come. The familiar ideology “what gets measured, gets managed” is just as true for sustainability as it is for the business applications for which the phrase was originally intended. Companies need quantitative assessment of sustainability to inform responsible decisions going forward, but also as a way to provide supportive evidence of any sustainably-focused mission statements they make. With increased focus on sustainability in recent decades has come an increased pull for accountability from businesses. A company needs to “know internally” that they are acting in such a way that is responsible and sustainable, but needs to be transparent and “show externally” that this is the case as well.

Internal accountability and consumer scrutiny are two of the major motivations behind the creation of sustainability reporting and certification programs. However, the choice of exactly which issues to report on and which metrics are the best indicators of these issues is a source of confusion for companies across sectors. The difficulty of deciding which metrics to use, when to use them, and how to measure them poses a challenge for green supply chain management. Further complicating the discussion is the fact that it is often not just one group of stakeholders who need to reach this agreement. Actors throughout the supply chain must negotiate which metrics to report using which data.

Global agricultural value chains are particularly complex, which makes sustainability assessment even more challenging. The value chains of agricultural commodities are typically characterized by low-value end products, expansive and nonlinear networks of actors, strong social and economic drivers on the producer and consumer ends, and wide variability due to environment and climate (Higgins et al., 2010). The complexity of the geographic and key actor networks of agricultural sustainability also increases the risk that the issues and indicators prioritized in sustainability assessment do not take into consideration multiple stakeholder perspectives. Sustainability issues considered important by executives of large agribusiness corporations or owners of agricultural product small businesses may differ from those considered important by farmers in developing countries.

Agriculture’s vulnerability to climate change is another reason why sustainability is so important in the industry, yet so difficult to define and assess. In the agricultural raw materials, beverage, and food sectors, climate change poses a threat by altering growing conditions, increasing pests and disease, and decreasing crop yields. A substantial portion of the supply chains of these sectors depend on natural resources and processes such as biodiversity, groundwater availability, air quality, and weather conditions. With this multitude of factors related to climate change and sustainability, it is easy to be overwhelmed when deciding which quantitative indicators of these factors to record and track.

Ultimately, businesses that rely on agricultural value chains attempt to choose a set of metrics that depict a story related to their product or make a compelling argument for their product’s sustainability or company’s sustainability as a whole.

Coffee Sector Context

Coffee is a prime example of a commodity crop that has a complex global value chain and is subject to the confusion surrounding sustainability efforts and measurement. Coffee beans are produced by the genus of plants Coffea, which includes anywhere from 25 to 100 species of coffee plants, specifically (NCA, n.d.). The two most common species in the commercial coffee industry are Arabica, which represents approximately 70 percent of the world’s coffee production, and Robusta, which accounts for roughly 30 percent of the global market (NCA, n.d.). Robusta is the heartier of the two species, as it prefers higher temperatures and is able to thrive at lower altitudes. Arabica, on the other hand, requires more specific growing conditions at higher altitudes and in rich soil, making it more difficult and expensive to cultivate (NCA, n.d.).

Coffee is grown worldwide in the equatorial zone located between 25 degrees North and 30 degrees South, an area also known as the “Bean Belt” (NCA, n.d.). This includes over 50 coffee producing countries around the world, according to the National Coffee Association of the U.S.A. (NCA, n.d.). The “Bean Belt” region can be seen in Figure 1, which depicts the major coffee exporting countries and members of the International Coffee Organization (ICO).

In 2018, over 168 million bags (60 kilograms, 132 pounds each) of coffee were produced by coffee exporting countries (ICO, 2019). The volume and geographic spread of coffee production is impressive, but the industry is also an economic powerhouse. According to Michigan Institute of Technology’s Observatory of Economic Complexity, the coffee industry represented $30.4 billion in exports as of 2017. Brazil, Vietnam, and Colombia were the top exporting countries of coffee in 2017 while the United States, Germany, and France were the top importing countries.

Despite the large volume of coffee traded worldwide, the price of coffee in the commodities market has suffered in recent years. In August of 2018, the international price of coffee, otherwise known as the C-price, dropped below $1 per pound for the first time in over a decade and has remained there ever since. While some industry actors say this is an urgent cause for concern, others are less worried, citing that the C-price is based on speculation and short-term projections which make it hard to accurately judge the state of the market.

The current state of the coffee industry has a lot to do with how the industry approaches sustainability today, but the complex network of entities in the coffee value chain is an inherent characteristic that motivated the industry’s interest in sustainability in the first place. Coffee is handled by a number of entities from “seed to cup”, and a single bag can have far-reaching effects even outside of its supply chain. It is important to acknowledge the various stakeholders involved and understand the details of their integrated roles before looking deeper into sustainability strategies for the industry.

Read more

Gerard, A., Lopez, M. C., & McCright, A. M. (2019). Coffee Roasters’ Sustainable Sourcing Decisions and Use of the Direct Trade Label. Sustainability, 11(19), 5437.

Elliott, K. A. (2018). What Are We Getting from Voluntary Sustainability Standards for Coffee. CGD Policy Paper. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, 34.

Collective Action Milieus and Governance Structures of Protected Geographical Indications for Coffee in Colombia, Thailand and Indonesia

Collective action is carried out by a group to pursue the members’ shared interests (Scott and Marshall 2009). According to Ostrom (1990, 29), “collective action takes place when a group of principals can organize and govern itself to obtain continuous joint benefits when all principals face temptations to free-ride, shirk, or act opportunistically in another way”. This paper addresses attempts by coffee producers to take collective action to safeguard Geographical Indications. Additionally, defending a collective reputational resource allows producers to cope with coffee market liberalization and protect well-known geographical names after the dismantling of quotas under the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) in 1989 and the accompanying shift in power to downstream roasters and retailers in the value chain (Daviron and Ponte 2005; Grabs and Ponte 2019).

Grabs and Ponte (2019) depict three main phases to understand the power dynamics along the global value chain for coffee: the ICA phase from 1962 to 1989; the liberalization phase from 1989 to 2008; and the diversification and reconsolidation phase (2008 to present). Earlier, Daviron and Ponte (2005) emphasized how value was increasingly embedded in the symbolic quality and in-person services (intangible quality attributes) of coffee. This implies that producers need to assume greater control of these immaterial or in-person means of quality production rather than selling a highly commercialized and standardized product (Samper et al. 2017) and this has manifested in various attempts at product differentiation, some of which are producer-driven (Fischer 2017; Jaffee 2007). These attempts include voluntary sustainability and quality standards such as Fairtrade, Organic, and Rainforest Alliance, but also include Geographical Indications (GIs) and producer involvement in “Cup of Excellence” events (Neilson et al. 2018; Quiñones-Ruiz et al. 2015; Teuber 2010).

The ability of sustainability standards, however, to induce significant change for producers has been increasingly questioned due in part to their mainstreaming and inability to ensure quality differentiation at the producer level (Bray and Neilson 2018; Grabs 2018; Mutersbaugh et al. 2008). Disillusionment with standards has encouraged some roasters to engage in direct “relationship coffees” to improve both producers’ livelihoods and their corporate images (Vicol et al. 2018). However, the Indonesian cases presented by Vicol et al. (2018) show that although initially participating producers (usually gathered into producer groups) are marginally better off, benefits from these relationships eventually accrue primarily to local elites. While sustainability standards and relationship coffees are essentially institutions designed and maintained by actors in the Global North, the protection of Geographical Indications (GIs) is distinct in that they involve standards framed, established and implemented by the producers themselves. As such, GI protection offers a possibility for producers to partake in symbolic quality construction and then protect those symbolic quality attributes through collective action and self-governing of rules for production, marketing, labelling, and surveillance.

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is a multilateral legal agreement between all member nations of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It provides an umbrella legal framework for GIs internationally, since it requires all signatory states to establish a national legal framework for GIs, although these vary considerably between countries. Under Article 22 of TRIPS, GIs are considered “indications which identify a good as originating in the territory of a Member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin”. This link between specific quality attributes and geography applies to all producers within a territory and so the explicit aim of quality differentiation requires collective action. GI protected goods are thus themselves collective goods derived from the use of shared local resources and assets (the place name), which require the cooperation and collective action of producers and processors (Barham 2003; Biénabe et al. 2013; Bowen and Mutersbaugh 2014). Biénabe et al. (2013) highlight the Karakul case as a “tragedy of the commons” that could have been avoided by designing collective institutional frameworks. Considerable rules, monitoring and sanctioning efforts are needed to preserve the identity and specific quality of the GI products, to develop their reputation and to effectively exclude illegitimate users. Indeed, the necessary institutions for collective action dealing with intellectual property rights are seen as an increasingly important focus within the commons’ literature (see van Laerhoven et al. 2020).

This paper sheds light on the types of actors involved and their role within the GI registration process, as explained by the institutional arrangements reached under the lens of collective action. It is noteworthy that according to the regulatory framework of the studied countries (Colombia, Indonesia and Thailand),1 group of producers (or government authorities on their behalf) are entitled to apply for GIs. Therefore, our premise for starting this article is based on the expectations within national legislations that collective action processes will be pursued. Our goal is to examine these collective action processes in greater detail. This analysis is based on Ostrom’s work dealing with collective action to analyze institutions, understood as “human-constructed constraints or opportunities within which individual choices take place and which shape the consequences of their choices” (McGinnis 2011, 170). As with the collective management of natural resources, GI protection also requires the design of specific rules for GI use (Quiñones-Ruiz et al. 2015, 2016). Factors both internal and external to the group, such as types of actors and their roles (attributes of the community), biophysical conditions, and rules-in-use (institutional arrangements) shape the structure of action situations (Ostrom 2010). Poteete et al. (2010) consider action situations as social places where actors make decisions, solve problems, fight and interact – linked to potential outcomes, costs and benefits. Actors represent various participants who individually take part in these specific action situations (Ostrom 2011).

We aim to understand the role of collective action and the nature of governance structures followed by producer groups for Protected Geographical Indications (PGI) in the coffee sector through a cross-country comparative study. This study addresses PGI protection following registration under the EU GI law only – not the mutual recognition that follows bilateral agreements between the EU and other countries. A particularity of EC Council Regulation 1151/2012 is its needed requirement for collective action when registering GIs, whether as Protected Geographical Indications (PGI) or as Protected Designations of Origin (PDO). This requirement is indicated by Article 49 of the Regulation, which states that “Applications for registration of names under the quality schemes referred to in Article 48 may only be submitted by groups who work with the products with the name to be registered.” The need for GI collective action is to be pursued by a ‘group’, which is understood as “any association, irrespective of its legal form, mainly composed of producers or processors working with the same product” (under Article 3). Furthermore, according to Article 7, the Product Specification, which is the basis for the GI registration and protection, should include: the name to be protected as a designation of origin or GI; a description of the product; the definition of the geographical area; evidence that the product originates in the defined geographical area; a description of the production method; the link between the quality or characteristics of the product and the geographical environment; the link between the quality of the product and the geographical environment or where appropriate, the link between the given quality, the reputation or other characteristic of the product and the geographical origin, and the name and address of the authorities or the bodies verifying compliance with the provisions of the Product Specification. PDOs are linked to a product that originates in a specific place and all production steps have to occur in the delimited geographical area, whereas under PGI protection only one production step is required to occur in the defined geographical area. In this paper, we examine four case studies where conformance to EU GI requirements (510/2006 and 1151/2012) is a common factor, and seek to understand how this particular need for collective action under EU law has manifested within coffee GIs, and to what effect. Our comparative study covers coffee producers in Colombia (one case), Thailand (two cases) and Indonesia (one case) who have registered PGIs in the EU in 2007, 2015 and 2017 respectively.

We apply a comparative case study approach drawing upon Ostrom’s (2007) IAD framework and the work done by Quiñones-Ruiz et al. (2016). While Quiñones-Ruiz et al. (2016) illustrated the transaction efforts and outcomes of diverse GI registration processes, we focus on the understanding of the collective action in coffee chains (e.g. actors involved, institutional arrangements and the outcome of the collective interactions among actors).

We apply a cross-country comparative case study approach. Indeed, Flyvbjerg (2006, 1) suggests “that a scientific discipline without a large number of thoroughly executed case studies is a discipline without systematic production of exemplars, and that a discipline without exemplars is an ineffective one”. The motivation to carry out this study commenced with an examination of Café de Colombia, which was the first PGI registered for coffee in the EU (Quiñones-Ruiz et al. 2015). By means of the DOOR database (an EU database that publishes and manages all registered PDOs/PGIs; EC 2019), we subsequently identified registered PGIs for coffee in Thailand and Indonesia, which had been less thoroughly analyzed than the relatively well-studied Café de Colombia PGI.

We therefore adopted a comparative approach to examine all four EU-registered PGIs for Arabica coffee (as of October, 2019): Café de Colombia PGI (2007), Kafae Doi Tung and Kafae Doi Chaang from Thailand (2015) and Kopi Arabika Gayo from Indonesia (2017). All four EU registrations followed an earlier registration within origin countries (Table 1), and were each coordinated by a leading organization: the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (FNC, thereafter called the “Federation”); the Mae Fah Luang Foundation under Royal Patronage (thereafter called the “MFLF”); the Doi Chaang Coffee Original Company, Ltd. (thereafter called the “DCCO”), and the Masyarakat Perlindungan Kopi Gayo (Gayo Coffee Protection Society, thereafter called the “MPKG”).

Prior to the fieldwork2 we carried out a literature review on GIs for coffee in general with a special focus on the selected cases and analyzed relevant documents such as registration documents found in the DOOR database (EC 2019). We conducted semi-structured interviews with value chain actors, experts and government authorities (Table 2). We aimed to collect a broad range of different insights and perspectives about the characteristics and dynamics of collective action among the diverse local actors. All questions were formulated in a non-directive open-ended manner, starting from simple to more complex questions. It was important to let the interviewee talk freely without interference. Translations were necessary in all cases (e.g. from Spanish to English; Bahasa Indonesia, and Gayo to English; Thai, Akha, Lisu, and Lahu to English). We used qualitative content analysis in which the meaning and interpretation of the text was the central aspect of the analysis (Patton 2002).

Based on the work done by Quiñones-Ruiz et al. (2016), and drawing upon Ostrom’s IAD framework, we present the four cases through the following common analytical approach: i) contextual setting of product and territory; ii) actors involved in the collective action (i.e. who was included and excluded and who initiated the process; iii) institutional arrangements (rules in use)3 and action arena where collective action efforts are designed and effected; and iv) the outcome of these arrangements for collective action. Additionally, cross-case triangulation and reflective loops (i.e. discussion of results with international and local experts and key informants) were aimed to support the validity of the overall comparative analysis (Yin 2009).

Protecting Geographical Indications Across Three Countries

Café de Colombia

Contextual setting of product and territory. Jesuits introduced Arabica coffee to Colombia in 1723, when it was first cultivated in the northeast – in los Santanderes (Palacios 1979). In 1927, growers founded the Federation, which has become perhaps the world’s longest-standing coffee producer organization, and which now represents the interests of Colombia’s estimated 540,000 coffee growers, 90% of whom are small and medium-sized landholders. Colombia is the third largest producing country after Brazil and Vietnam (ICO 2018), and domestic coffee consumption continues to increase (FNC 2013; Ocampo-López and Álvarez-Herrera 2017). Colombia has a solid reputation for quality and “Colombian Milds” are a key global price indicator for quality Arabica. According to the Product Specification found in the DOOR database (EC 2019; FNC 2007, 6), coffee cultivation covers an area of approximately 800,000 hectares throughout the mountainous regions of Colombia. The coffee-growing area is characterized by common climatic and orographical conditions, producing coffee beans with a clean taste, of medium/high acidity and body, and a full and pronounced aroma. Accordingly, the quality of Colombian coffee also depends on common factors such as the wet processing method, selective harvesting involving a significant amount of manual labor, cultivation by long-established and skilled producers, and the use of careful selection and classification processes (FNC 2007).

Actors involved in the collective action. GI protection was a producer-led effort (Quiñones-Ruiz et al. 2015) embedded in the institucionalidad cafetera, a well-organized and robust structure consisting of 376 Municipal Committees, 15 State Committees, a Steering Committee, the National Coffee Committee and the National Congress of Coffee Producers. The Congress, which meets annually, is the peak authority of the Federation and is comprised of delegates of the state committees. The Federation has set up partnership agreements with organizations such as Almacafé (quality control), Cenicafé (research center) and cooperatives (coffee purchasing points) (Barjolle et al. 2017; Quiñones-Ruiz et al. 2015), which enables the management of coffee production, quality control and commercialization. The role and responsibility of Colombian public authorities, such as the Superintendence of Industry of Commerce (SIC) was confined to national registration processes only.

Institutional arrangements (rules in use) and action arena. There were several important antecedents to GI registration, including the branding of Colombian coffee using the Juan Valdez symbol in 1959, and its subsequent protection as a trademark in 1960 (Reina et al. 2007). The Federation thus became familiar with trademarks and certification marks in the United States of America and Canada, which have historically constituted important export markets for Colombian coffee. Therefore, GI protection was considered as a strategic opportunity to safeguard Colombian origin and quality (reputation) both domestically and abroad (Quiñones-Ruiz et al. 2015). In the 2004 Coffee Congress, their members jointly decided to pursue GI protection. This required a significant administrative and financial effort by the Federation staff to navigate through the legal framework, engage lawyers, accumulate GI knowledge, elaborate protocols on registration procedures, sample collection and analysis (Quiñones-Ruiz et al. 2015) in order to comply with EU GI law. There are three issues to highlight regarding registration: i) since Café de Colombia covers all coffee-producing states, there were no conflicts between producers (in contrast to the later GI registration of Café de Nariño, see Giovannucci et al. 2009); ii) the GI strategy was primarily conceived and decided by Federation staff who work on behalf of producers; iii) not all value chain actors were initially involved in the GI project, as it excluded buyers, traders, exporters, and roasters, for whom rules governing the use of the PGI were established post hoc (Quiñones-Ruiz et al. 2015). During the annual Coffee Congress in 2004, it was jointly decided to start the GI process only under the producers’ lead and later allow access to international players to become voluntary GI users. This was one of the main independent institutional decisions made by Federation staff prior to registration.

The outcome of these arrangements for collective action. Although the owner of the GI right is the government, the Federation is entitled to administer and manage the GI. Any value chain actor (e.g. any coffee producer irrespective of size of holding, trader or roaster) who follows the GI rules (Product Specification) can become a GI user. The Federation has been instrumental in supporting GI registration not only in Colombia and the EU, but also in Switzerland, Ecuador and Peru. Following Café de Colombia PGI registration, six local GIs have been subsequently protected: Café de Nariño; Café de Cauca; Café del Huila; Café de Santander; Café de la Sierra Nevada; and Café del Tolima (FNC n. d.).

Thailand (Kafae Doi Tung, Kafae Doi Chaang)