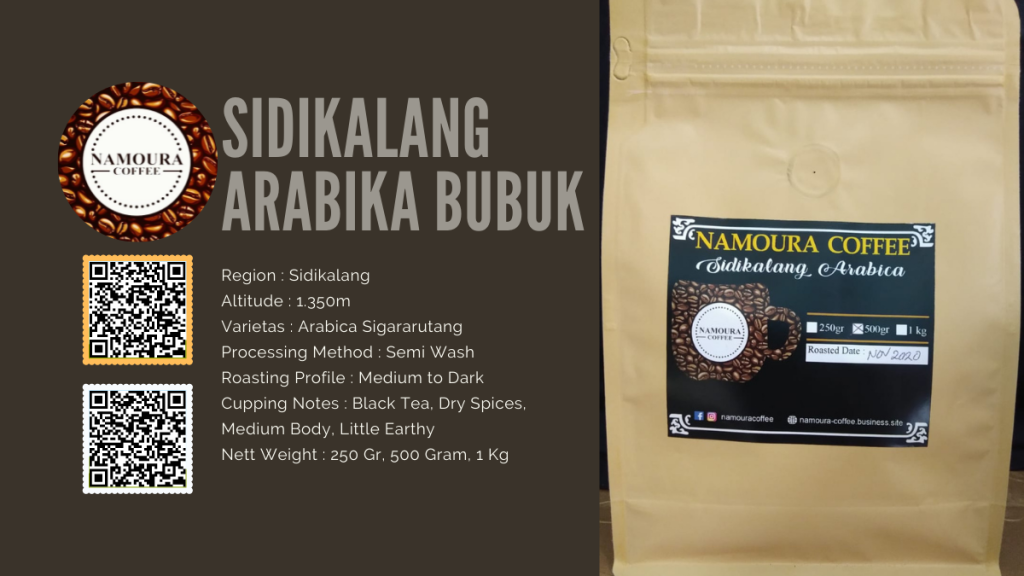

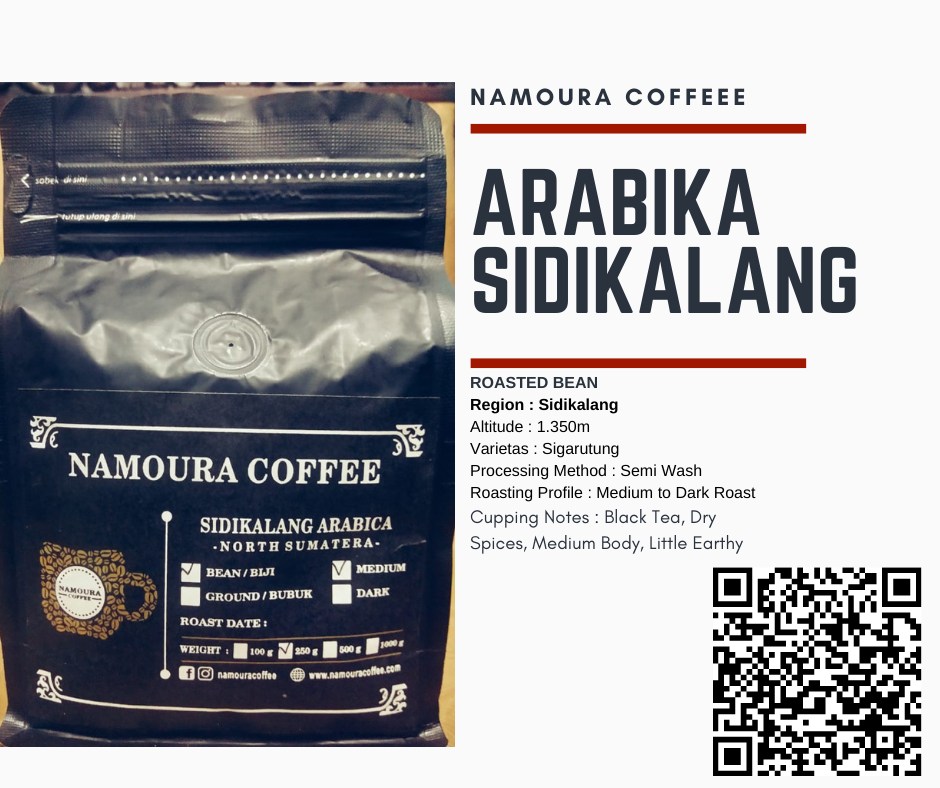

Namoura Arabika Sidikalang Bubuk

Mengenal beragam jenis kopi yang sudah mendapat predikat sebagai kopi terbaik tentu tak lepas dari jenis kopi satu ini, kopi Sidikalang. Jenis kopi satu ini ternyata tidak kalah populer dengan jenis kopi yang lain seperti kopi Luwak. Sama sama berasal dari Indonesia, kopi Sidikalang ternyata juga mendapat pengakuan dari banyak pencinta kopi tidak hanya di Indonesia tapi juga di negara negara lain seperti negara Amerika Serikat. Pertanyaannya, lalu apa yang menjadikan kopi Sidikalang ini begitu spesial?

Kopi Sidikalang ini juga sangat terkenal akan cita rasanya yang unik dan lezat. Kopi Sidikalang berasal dari Sumatera, tepatnya di sebuah ibukota kabupaten Dairi, Sumatera Utara.

Selain mendapat pengakuan dari para penikmat kopi di negeri sendiri, negeri Indonesia, kopi Sidikalang ternyata mampu bersaing dengan jenis kopi lain termasuk kopi Brazil. Hal ini tentunya bukan sesuatu yang mengejutkan karena kopi Sidikalang memiliki cita rasa khas yang tidak dimiliki oleh jenis kopi lain. Di tempat asalnya sendiri, pulau Sumatera, boleh dibilang kopi Sidikalang adalah rajanya kopi.

Namoura Coffee dengan bangga menghadirkan ikon kopi sumatera ini untuk kalian para penikmat kopi berkualitas, Arabika Sidikalang Bubuk yang memiliki kadar kafein lebih tinggi dibanding jenis kopi lain pada umumnya, aroma khasnya adalah manis karamel yang berpadu dengan sedikit rasa rempah. Kemudian, after taste khasnya adalah perpaduan antara citrus, dark chocolate dan fruity yang cukup segar. Ikon kopi Sumatera ini kami hadirkan dalam bentuk tiga kemasan, yakni: 250 gram, 500 gram, dan 1 Kg.

Namoura Gayo Arabics

Coffee from Takengon, Center of Aceh or commonly called Aceh Gayo coffee is already famous in the world. As the name implies, this coffee is managed by the Gayo people who are original Aceh residents. This type of coffee is one of the most widely consumed coffees as well as exported abroad. Premium product quality, with professional quality control, Quality control by machine and manual sorting process (Double Picked).

Specifications:

- Single Origin Aceh Gayo Arabica Coffee with Grade 1 quality

- Processing Method: Semi-washed

- Altitude: +/- 1,400m

- 11-13% Moisture; Defect 0-3%

- Quality guaranteed

- Suitable for roasters and also coffee connoisseurs who like to roast by themselves

Come join us here with our Namoura Gayo Arabics.

Can Democracy Reduce Inequality

Despite two decades of social policies targeting poverty and inequality, Latin America remains one of the most economically unequal regions in the world. Recurrent protests motivated by economic grievances have been a regular reminder of this reality. The ongoing health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic has disproportionately harmed already vulnerable populations, undoing some of the progress made. At the same time, democracy has taken root in the region, and participation in elections is growing. Then why hasn’t democracy been more effective in resolving Latin America’s persistent inequality?

Research shows voters are not able to make their demands for greater redistribution heard, while governments are not implementing redistributive policies at the desired pace. Reasons include unequal political participation, institutional bias against redistribution, and vote buying. Until such impediments are removed, democracy’s impact on inequality will remain limited.

Between 2000 and 2018, income inequality in Latin America, as measured by the Gini index, gradually fell from 53.3 to 45.7. During the same period, government spending on social protection steadily increased by almost one percentage point of GDP. While these trends seem promising, inequality in Latin America remains high and social spending low by the standards of more advanced economies. For example, the thirty-six countries of the OECD reported a Gini index of only 33.2 in 2018. That is puzzling, given that at least on paper, Latin America is built on similar economic and political principles—market economies and representative democracies. One would expect that the democratic process, which by design is based on the egalitarian principle of “one person, one vote”, would lead to policies that reduce market inequalities. In other words, in a well-functioning democracy, inequality should to some extent be self-correcting. Why isn’t this happening to a greater degree in Latin America?

Weak Voter Demand for Policies that Lower Inequality

A first explanation is that voter demand for inequality-reducing policies remains relatively weak. Lack of voter pressure can be seen in limited and unequal political participation. Despite the widespread use of compulsory voting, voter turnout in the region has remained below 70% on average. More importantly, turnout is biased in a way that is detrimental to the poor, as voting is less common among the less educated and the less wealthy.

Even when they do vote, the less well-off are less informed, and thus less effective in choosing candidates that represent their economic interests. The poor are the greatest beneficiaries of basic public services, such as public education and health care. Unfortunately, voter demand for government investments in these public goods is tenuous, either due to low trust in the ability of public officials to spend public resources in these areas effectively, or due to a preference for immediate benefits such as cash transfers, at the expense of longer-term benefits such as high-quality education and public safety.

Weak Supply of Policies Designed to Reduce Inequality

A second explanation is that the policymaking process may fail to internalize popular demand for redistribution. In some cases, this occurs because political institutions can be manipulated by incumbents to retain power, for example through legislative malapportionment. Others argue that elements of the elite gain access to and remain in power using campaign donations from narrow interest groups, obviating the need to rely on broad popular support.

More recent research has shown that vote buying by political candidates, a prevalent phenomenon in many Latin American democracies, subverts the normal functioning of the budget process. Voters targeted with vote buying prior to an election may receive no government benefits after the election. As poorer voters are more susceptible to vote buying, they are often left unrepresented in the subsequent negotiations over the budget. Thus, vote buying crowds out redistributive spending that could reduce inequality.

Stronger Democracies Better Alleviate Inequality

In a chapter of the recent IDB report entitled The Inequality Crisis I present new data patterns that support the idea that the strength of democracy matters for the alleviation of inequality. I use the Economist Intelligence Unit democracy index to rank democratic quality along five dimensions. Among Latin American countries, stronger democracies provide more redistributive spending. At one end of the spectrum, Nicaragua spends less than 1% of GDP on social protection, compared to almost 7% in Uruguay, at the other end of the spectrum. Interestingly, stronger democracies are also characterized by higher voter turnout and fewer protests. This suggests that voting, rather than protesting, is a catalyst for government redistribution. Protests appear to be a symptom of unmet economic expectations.

Some development institutions, such as the UNDP, have suggested that inequality may be one of democracy’s greatest weaknesses. As the less well-off are economically marginalized, they become more disengaged with the democratic process. However, a weaker democracy may also fail to alleviate inequality. Overcoming this vicious circle remains a challenge for Latin America’s young democracies. Political and civic leaders in the region should renew their commitment to strengthening democratic institutions, chief among them free elections, civic liberties, and independent media. Over time, better-functioning democracies should improve economic equity. Democracy can certainly reduce inequality, as long as it functions as intended.

The Wage Curve across the Wealth Distribution

The uneven distribution of wealth in society is commonly perceived as a matter of concern per se for inequality-averse policymakers. However, being wealth-poor or wealth-rich is also correlated with outcomes in the labour market. This column examines how wages and unemployment vary across the relative distribution of personal wealth in Norway, focusing on the wage-to-unemployment ratio across the different percentiles of the wealth distribution. It finds that wealth-poor individuals cannot escape low labour incomes regardless of the unemployment rate they face, while the unemployment elasticity of wages is substantially higher for wealth-rich individuals.

Economists have long come to accept inequality in the pace of wealth accumulation across the wealth distribution as a more accurate measure of inequality than income (Mankiw 2015).

However, the academic debate has in recent years focused on documenting the extent to which both capital income and wealth are concentrated in the hands of a few individuals (Piketty 2014, see also König et al. (2020) for a recent survey).

Stiglitz (2015) highlights the need to document the changing distribution of income and wealth, but also calls for new complementary facts to be studied. In their Vox column, Kanbur and Stiglitz (2015) conclude: “We need to focus on the interaction between income from physical and financial capital and income from human capital in determining snapshot inequality”.

Along these same lines, our research highlights the extent to which the distribution of wealth holdings is unambiguously associated with outcomes in the labour market (Iacono and Ranaldi 2020). We argue that the relative distribution of personal wealth is relevant not only per se but also to better comprehend the role of wealth in shaping individuals’ working trajectories over the life cycle.

Personal wealth and the labour market

The empirical relationship between gross wages and the unemployment rate (the so-called wage curve) is a matter of great relevance to policymakers and has been studied extensively by economists. Do wages respond to changes in the unemployment rate, for instance? I.e. do wages adjust if there is an unexpected surge in unemployment, as in the current pandemic? Does the unemployment rate vary when wages rise? This wage curve has been estimated previously across space, both at the national (Blanchflower and Oswald 1994) and regional levels (Blanchflower and Oswald 1995). In our paper, we estimate the wage curve through the lens of the personal wealth distribution. Ranking individuals according to their wealth holdings allows us to uncover several stylized facts related to labour market outcomes that are associated with wealth, rather than with traditional explanatory variables such as educational attainment or parental background. Thanks to the rich and fine-grained administrative data on personal wealth in Norway, our sample covers the entire population of residents between 2000 and 2015. Based on this large-scale sample, we document several novel facts about the wage curve across the wealth distribution.

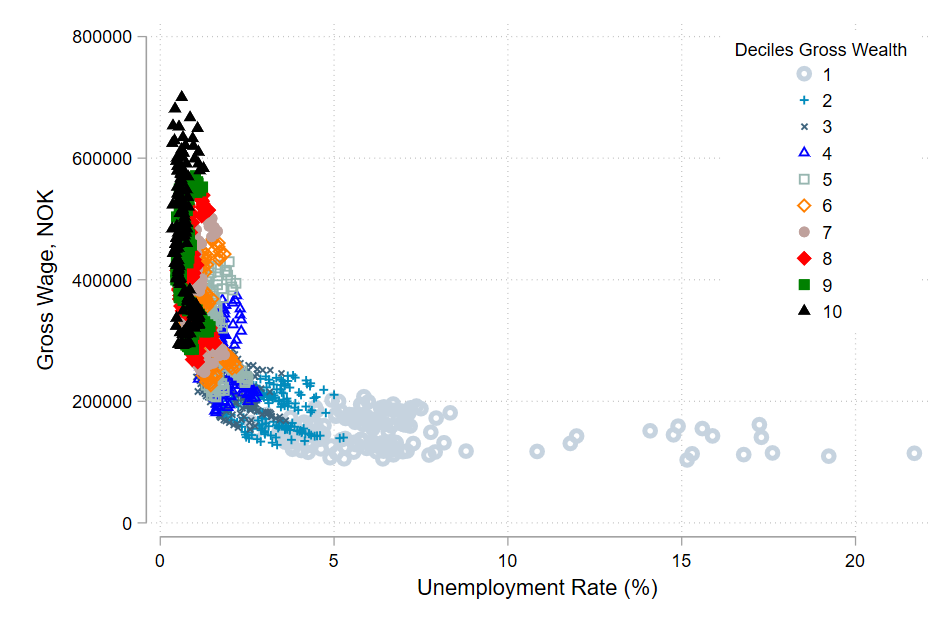

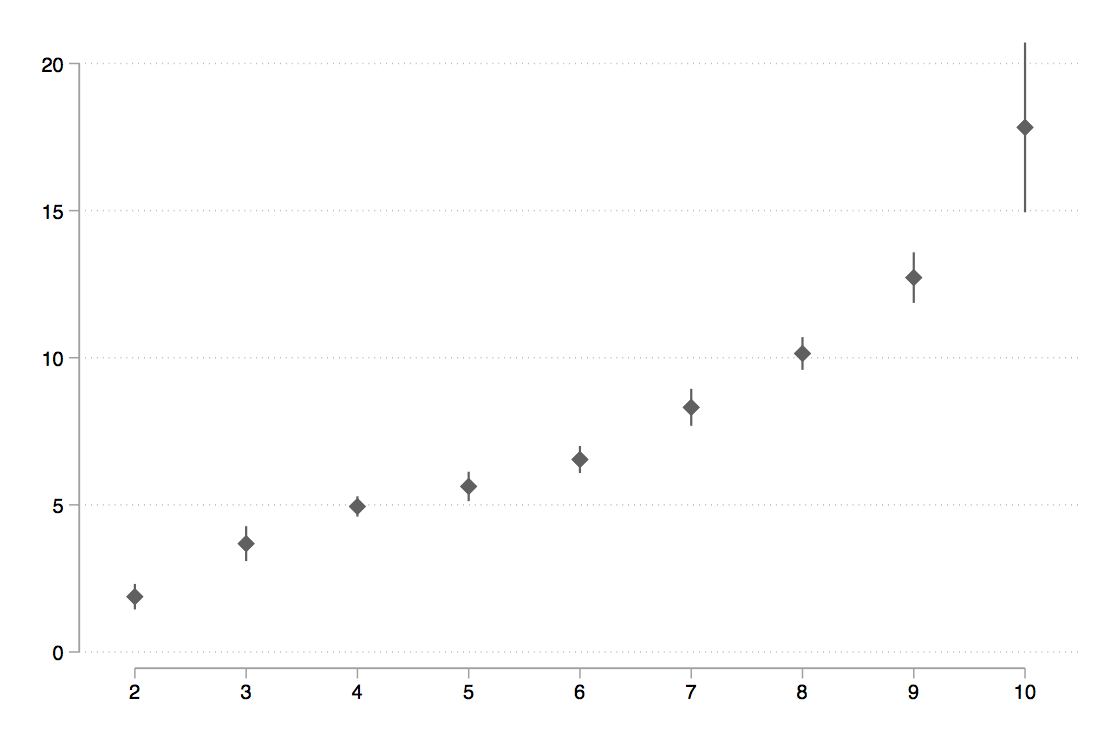

The first stylised fact shows that the elasticity of the wage curve – how gross wages change with a change in the unemployment rate – increases monotonically with gross wealth, as shown in Figure 1.

This figure shows that wealth-poor individuals cannot escape low labour incomes regardless of the unemployment rate they face (a sort of double poverty trap in the sense of low income and low wealth), while variation in unemployment is much lower for wealth-rich individuals. The latter enjoy a higher range of wage incomes, regardless of the unemployment rate they face. Note that we always compare individuals in the same percentiles of the wealth distribution in our analysis.

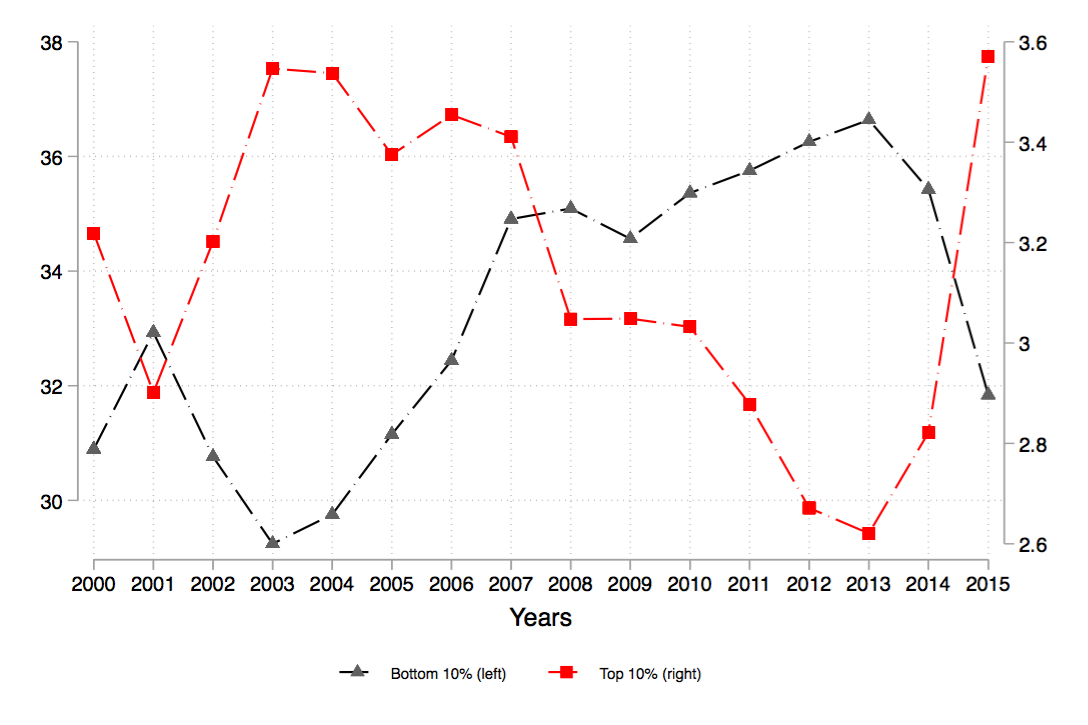

Second, we highlight that the distribution of unemployment across the wealth ladder is highly uneven when comparing the bottom with the top of the wealth distribution. In fact, we construct the first distribution of unemployed individuals across the wealth ladder between 2000 and 2015 in Norway and show that the share of unemployed individuals in the bottom 10% of the wealth distribution is ten times larger than the share in the top 10% of the distribution in Norway (compare Figure 2).

In our view, the unemployment share at the bottom of the wealth distribution can be considered a measure of the vulnerability of the unemployed. Assume that two countries have the same overall unemployment rate but a different share of unemployed at the bottom of the wealth distribution; then, an economic shock might be more harmful to the country with a higher share of unemployed at the bottom of the distribution. In fact, if an economic shock, such as a financial crisis or a pandemic, should suddenly occur, the ability to economically overcome that shock is a positive function of the wealth held by the unemployed.

We also analyze how the relationship between wages and unemployment changes when individuals move along the wealth ladder. To answer this question precisely, one would ideally need to follow the same individuals across the life cycle to disentangle the effect of switching from one decile of the wealth distribution to another. Alternatively, we provide a first step in this direction by estimating the relationship between wealth deciles (our preferred measure of wealth status) and the wage-to-unemployment ratio, summarizing the principal labour market characteristics. Whenever the wage-to-unemployment ratio is low, we have a labour market with rather stagnant wages and sustained rates of unemployment. In contrast, a high wage-to-unemployment ratio is associated with high wages and rather low unemployment rates. Figure 3 confirms the findings presented in Figure 1 of this column, showing that the wage-to-unemployment ratio (vertical axis) increases across wealth deciles (horizontal axis), indicating that belonging to higher deciles of the wealth distribution is associated with better wages and lower unemployment.

All in all, these findings show the extent to which wealth inequality shapes labour market outcomes. This further motivates the need to better design wealth redistribution policies. In addition, the stylized fact that wealth-poor individuals are trapped in a state of low income regardless of the unemployment rate does not easily follow from standard competitive labour market modelling. Hence, we advocate for more evidence on the matter, not only to inform public policies aimed at improving employment opportunities but also to improve the macroeconomic modelling of the labour market. Moreover, we think that our main result, whereby the slope of the wage curve is a positive function of gross wealth, can be incorporated in any macroeconomic model of the labour market that wishes to account for wealth inequality in its dynamics.

Concluding remarks

The new stylized facts of our column on wealth and its role in the labour market can be summarised as follows:

- The distribution of unemployed people across the wealth ladder in Norway is highly uneven.

- The negative slope of the wage curve, previously estimated in the national or regional space, is also confirmed within the (distributive) wealth space.

- The wage-to-unemployment ratio increases monotonically with increasing gross wealth.

- Wealth-poor unemployed individuals are substantially more vulnerable to economic shocks than wealth-rich individuals since the former also receive lower wages in the labour market.

References

Blanchflower, D G and A J Oswald (1994), “Estimating a Wage Curve for Britain 1973-90”, The Economic Journal 104 (426): 1025–1043.

Blanchflower, D G and A J Oswald (1995), “An introduction to the wage curve”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 9(3): 153-167.

Iacono, R and M Ranaldi (2020), “The Wage Curve across the Wealth Distribution”, Economics Letters 196, 109580.

Kanbur, R and J Stiglitz (2015), “Wealth and income distribution: New theories needed for a new era”, VoxEU.org, 18 August.

König, J, C Schröder and E N Wolff (2020), „Wealth Inequalities“, In: Zimmermann, K F (eds) Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics, Springer.

Mankiw, N G (2015), “Yes, r > g. So What?”, American Economic Review 105 (5): 43-47.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the XXIst Century, Harvard University Press.

Stiglitz, J E (2015), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals: Parts I-IV”, NBER Working Papers 21189-21192.

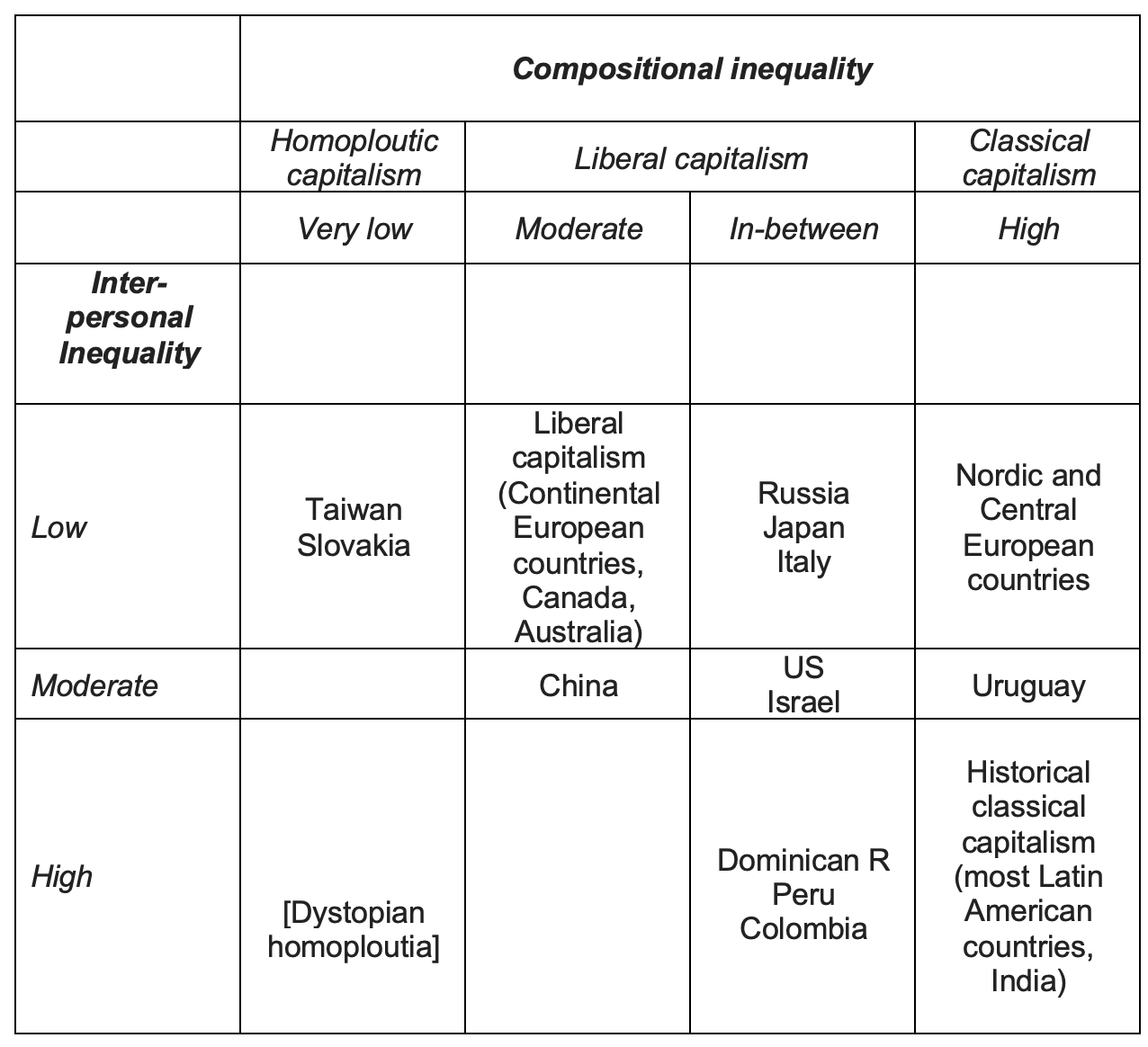

Capitalist Systems and Income Inequality

Similar levels of income inequality may coexist with completely different distributions of capital and labor incomes. This column introduces a new measure of compositional inequality, allowing the authors to distinguish between different capitalist societies. The analysis suggests that Latin America and India are rigid ‘class-based’ societies, whereas in most of Western European and North American economies (as well as in Japan and China), the split between capitalists and workers is less sharp and inequality is moderate or low. Nordic countries are ‘class-based’ yet fairly equal. Taiwan and Slovakia are closest to classless and low inequality societies.

Similar levels of income inequality may be characterised by completely different distributions of capital and labour. People who belonged to the highest income decile in the US before WWII received mainly capital incomes, whereas in 2010 people in the highest decile earned both high labour and capital incomes (Piketty 2014). Yet the difference in their total income shares was small.

Different distributions of capital and labour describe different economic systems. Two polar systems are particularly relevant. In classical capitalism – explicit in the writings of Ricardo (1994 [1817]) and Marx (1992 [1867], 1993 [1885]) ¬– a group of people receives incomes entirely from ownership of assets while another group’s income derives entirely from labour. The first group (capitalists) is generally small and rich; the latter (workers) is generally numerous and poor, or at best with middling income levels. The system is characterised by high income inequality.

In today’s liberal capitalism, however, a significant percentage of people receive incomes from both capital and labour (Milanovic 2019). It is still true that the share of one’s income derived from capital increases as we move higher in the income distribution, but very often the rich have both high capital and high labour incomes. While inter-personal income inequality may still be high, inequality in composition of income is much less.

The purpose of our study is to introduce a new way of looking at inequality that allows us to classify empirically different forms of capitalism. In addition to the usual inter-personal income inequality, we look at inequality in the factoral (capital or labour) composition of people’s incomes. The class analysis (where class is defined narrowly depending on the type of income one receives) is thus separated from the analysis of income inequality proper.

Which countries around the world are closer to classical, and which to liberal capitalism? Does classical capitalism display higher inter-personal income inequality than liberal capitalism? Can we find what we term ‘homoploutic’ societies – where everyone has approximately the same shares of capital and labour income? Would such homoploutic societies display high or low levels of income inequality?

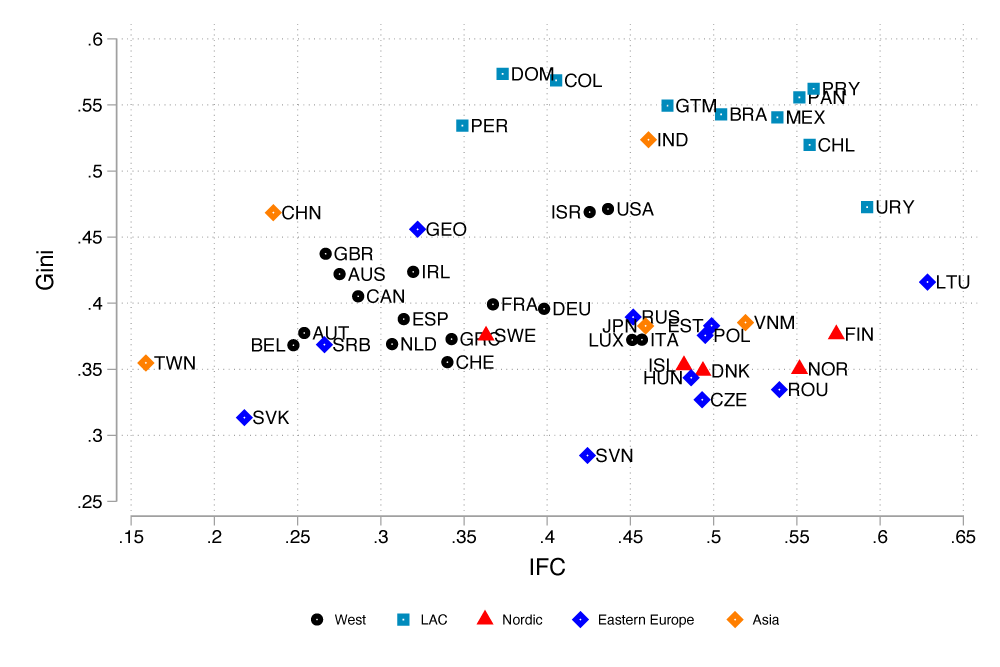

To answer these questions, in Ranaldi and Milanovic (2020) we adopt a new statistic, recently developed by Ranaldi (2020), to estimate compositional inequality of incomes: the income-factor concentration (IFC) index. The income-factor concentration index is at the maximum when individuals at the top and at the bottom of the total income distribution earn two different types of income, and minimal when each individual has the same shares of capital and labour income. When the income-factor concentration index is close to one (maximal value), compositional inequality is high, and a society can be associated to classical capitalism. When the index is close to zero, compositional inequality is low and a society can be seen as homoploutic capitalism. Liberal capitalism would lie in-between. Negative values of the income-factor concentration index, which describe societies with poor capitalists and rich workers, are unlikely to be found in practice.

By applying this methodology to 47 countries with micro data provided by Luxembourg Income Study from Europe, North America, Oceania, Asia, and Latin America in the last 25 years and covering approximately the 80% of world output, three main empirical findings emerge.

First, classical capitalism tends to be associated with higher income inequality than liberal capitalism (see Figure 1). Although this relationship was implicit in the minds of classical authors like Ricardo and Marx, as well as in recent studies of pre-WWI inequality in countries that are thought to have had strong class divisions (Bartels et al. 2020, Gómes Léon and de Jong 2018), it was never tested empirically.

Second, three major clusters emerge at the global scale. The first cluster is the one of advanced economies, which includes Western Europe, North America, and Oceania. Relatively low to moderate levels of both income and compositional inequality characterize this cluster. The US and Israel stand somewhat apart from the core countries since they display higher inequality in both dimensions.

Latin American countries represent the second cluster, and are, on average, characterised by high levels in both inequality dimensions.

The third cluster is composed of Nordic countries and is exceptional insofar as it combines low levels of income inequality with high compositional inequality. This is not entirely surprising: Nordic countries are known to combine wage compressions with ‘socially acceptable’ high returns to capital (Moene and Wallerstein 2003, Moene 2016). Such compromise between capital and labour (reached in the early 1930s) has put a cap on earning inequality within the region (Fochesato and Bowles 2015) but has left wealth inequality untouched (Davies et al. 2012). By drastically reducing the progressivity of capital income taxation (Iacono and Palagi 2020), income tax reforms during the 1990s have worked in the same direction.

Several other results are found. Many Eastern European countries are close to the Nordic cluster. Some (Lithuania and Romania) have very high compositional inequality, likely the product of concentrated privatisation of state assets. India is very similar to the Latin American cluster, displaying a class-based structure with high levels of income inequality.

Taiwan and Slovakia are, instead, the most ‘classless’ societies of all. They combine very low levels of income and compositional inequality. This makes them ‘inequality-resistant’ to the increase in the capital share of income. In other words, if capital share continues to rise due to further automation and robotics (Baldwin 2019, Marin 2014), it will not push inter-personal inequality up: everybody’s income would increase by the same percentage. The link between the functional and personal income distribution in such societies is weak – the topic of a previous VoxEU column by Milanovic (2017b). It is also interesting that Taiwan is both more ‘classless’ and less unequal than China.

The third, and perhaps most striking result that emerges from our analysis is that no one country in our sample occupies the north-west part of the diagram. We find no evidence of countries combining low levels of compositional inequality (like those of Taiwan and Slovakia) with extremely high levels of income inequality (like in Latin America).

To conclude, we propose a novel taxonomy of varieties of capitalism on the basis of the two inequality dimensions (Table 1). We believe such taxonomy brings a strong empirical and distributional focus into the literature on the varieties of capitalism, as well as a larger geographical coverage.

References

Baldwin, R (2019), The Globotics Upheaval: Globalization, Robotics and the Future of Work, Princeton University Press.

Bartels, C, F Kersting and N Wolf (2020), “Testing Marx: Inequality, Concentration and Political Polarization in late 19th Century Germany”, German Institute for Economic Research.

Davies, J, R Lluberas and A Shorrocks (2012), Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report 2012.

Fochesato, M and S Bowles (2015), “Nordic exceptionalism? Social democratic egalitarianism in world-historic perspective”, Journal of Public Economics 127: 30-44.

Gómes Léon, M and H J de Jong (2018), “Inequality in turbulent times: income distribution in Germany and Britain, 1900–50”, Economic History Review.

Iacono, R and E Palagi (2020), “Still the Lands of Equality? On the Heterogeneity of Individual Factor Income Shares in the Nordics”, LIS working papers series 791.

Marin, D (2014), “Globalization and the Rise of the Robots”, Vox.EU.org, 15 November.

Marx, K (1992 [1867]), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy 1, translated by B Fowkes, London: Penguin Classics.

Marx, K (1993 [1885]), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy 3, translated by D Fernbach, London: Penguin Classics.

Milanovic, B (2017a), “Increasing Capital Income Share and its Effect on Personal Income Inequality”, in H Boushey, J Bradford DeLong and M Steinbaum (eds) After Piketty. The Agenda for Economics and Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Milanovic, B (2017b), “Rising Capital Share and Transmission Into Higher Interpersonal Inequality”, Vox.EU.org, 16 May.

Milanovic, B (2019), Capitalism, Alone, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Moene, K O and M Wallerstein (2003), “Social democracy as a development strategy”, Department of Economics, University of Oslo 35/2003.

Moene, K O (2016), “The Social Upper Class under Social Democracy”, Nordic Economic Policy Review 2: 245–261.

Ricardo, D (2004 [1817]), The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, London: Dover publications.

Ranaldi, M (2020), “Income Composition Inequality”, Stone Center Working Paper Series 7.

Ranaldi, M and B Milanovic (2020), “Capitalist Systems and Income Inequality”, Stone Center Working Paper Series 25.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, translate by A Goldhammer, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

How Inequality Undermines Democracy?

Inequality has been on the rise over the last three decades, and has been a pervasive issue in the recent U.S. national election. On one level, income inequality is a non-issue in a market economy where there will always be winners and losers. In a market where individuals are free to make choices and reap the rewards of the choices they make, it is a given that some will wind up with more than others. We cannot all be equal because we don’t all have the same natural endowments. Those with certain skills and abilities will often wind up with more than those without. And those who went to school to train for specific occupations that pay well will earn more than those who did not. In short, skilled workers will earn more than non-skilled workers. Consequently, in an increasingly global economy where there will be two classes — skilled and educated workers at the top earning high wages and unskilled and poorly educated workers at the bottom earning low wages — there is bound to be inequality. Moreover, as these trends continue, the gap between the top and the bottom is only bound to grow. On another level, however, income inequality is a seminal issue because of what it really speaks to: the disappearance of the middle class. Inequality per se may not be the problem; rather it is the rate of increase in inequality. In this essay, I argue that to the extent that inequality effectively speaks to a shrinking middle class it represents a threat to democracy.

Rising Inequality

Income inequality is an amorphous concept. When we talk about income inequality we are often talking about the gap between the top and the bottom. The extent to which it is a problem is contingent on just how it is measured. General income inequality, as measured by the ratio of the incomes of the top fifth of the population to those of the bottom fifth, for instance, includes in all income; not just income earned laboring. For those at the top this can include wages, interest and dividend income.[i] For those at the bottom this can include income supports, which are usually subsidies or in-kind assistance that has the effect of boosting the wages of those at the bottom or their effective purchasing power. Income at the bottom, then, often includes wages plus these supports, whether through public assistance transfer programs and/or disability programs. Therefore, wage income will not be the same as income inequality, and this gap between the top and bottom will tend to be less.

General income inequality has in recent decades been on the rise. Those at the top of the distribution have seen their incomes increase while those at the bottom have seen their incomes decrease in real terms. Prior to 1973, the incomes of families in the bottom fifth of the income distribution in the U.S. grew more rapidly than the income of families in other countries. After 1973 low-income families in the U.S. experienced a steady decline in real income, especially from the late 1970s through the middle of the 1990s. Between 1979 and 2007, the top one percent of families had 60 percent of the income gains while the bottom 90 percent only had about 9 percent of those income gains (Belman and Wolfson 2014). Income inequality, especially after 1980, exploded with the top decile share of the national income rising to between 45-50 percent in the 2000s. This may nonetheless understate the problem, which in recent years has been couched as the very top pulling away from the rest because a subclass of “supermanagers” — those at the top of the distribution with great ability and talent, who in some cases were viewed as “superstars” because they were able to make their companies profitable and return a high rate of return to shareholders — emerged who were earning extremely high compensation (Hacker and Pierson 2010; Piketty 2014).

The Threat to Democracy

Democratic theory assumes a society of free, equal, and autonomous individuals. Although democracy may have different meanings for different people, an ideal of democracy is that all individuals are supposed to have equal standing. This means that each individual is equal before the law, has the same vote as other individuals, the same right to express oneself in the political sphere, and perhaps most importantly the same potential to influence what government does, even if they opt not to exercise that potential. All citizens, then, have the same access to governing institutions. Within this theoretical construct, which may also characterize American democracy, money is supposed to be irrelevant to one’s standing. Both the rich and the poor are equal before government (Hacker and Pierson 2010). This conception of equality, otherwise known as procedural equality is not usually concerned with how resources, wealth and income are distributed, but with how individuals stand in relation to one another. Individuals can have more than others so long as they are equal in terms of their legal and political standing. Procedural equality is especially critical to democratic society because it serves to secure another essential condition: personal freedom, which is also a necessary condition for individuals to function autonomously. The greater their autonomy, the more likely they are to participate in the democratic process. Individuals are free to pursue their goals and objectives—i.e. self-interests—so long as their pursuit does not interfere with others’ ability to pursue their own goals and objectives. In a very basic sense, and certainly within the context of classical political thought, this is what it means to talk about personal independence or autonomy. But as Tocqueville observed there cannot be real political equality without some measure of economic equality as well, because a society with great concentrations of poor people can be dangerous (Zetterbaum 1987). Therefore, economic inequality could pose serious problems in a procedural democracy.

Why, then, might inequality be so dangerous to democracy? According to Acemoglu and Robinson (2006), unrest is often a consequence of inequality. And yet, changes are more likely to occur in those societies with greater inequality between elites and citizens. The more equals the society, the less likely are the masses to demand democratization. Democratization requires that society be sufficiently unequal so that the threat of revolution is credible. Therefore, elite may be willing to begin a transition by extending the right of franchise because it is in its interests to do so. The transition effectively preserves the status quo by staving off the threat of revolution, which in the end may preserve the power base of the elite. Yet, the elite only democratizes to the degree necessary to stave off the threat of revolution, because the former effectively limits the power of the majority by diluting popular pressure and undermining the power of the majority. Democratization refers to achieving voice through fair procedures. But democratization could mean achieving greater equality through the redistribution of resources aimed at achieving equality of result.

Economic equality, then, effectively promotes democracy because it effectively reduces the pressure for redistribution, which could occur as a byproduct of mass revolution and the subsequent creation of an authoritarian regime (Boix 2003). More unequal distribution of wealth increases the redistributive demands of the population and the ultimate level of taxes in a democratic system. But what happens when the political system is unresponsive to a so-called democratic vote on the tax rate?

A truly democratic regime would not simply take away from the wealthy elite for the benefit of the masses, but it might set a higher tax rate for purposes of redistribution. In a democracy, everybody votes on the tax rate in accordance with what is known as the median voter theorem. This holds that the more inequality there is the greater will be the distance between the median income and society’s average income. The greater the distance, the more calls there are for redistribution, and it is the distance itself that effectively determines the tax rate (Meltzer and Richard 1981).

On an individual level, unequal distribution of wealth and income, however, may adversely affect individuals’ ability to participate in the democratic process as equals. It may result in procedural inequality to the extent that those lacking in wealth and income may not enjoy the same access to political and policy officials as those who possess wealth and income enjoy. With a greater concentration of wealth at the top, elites are in a better position to use their wealth toward the attainment of their political and other ideological objectives (Bachrach and Botwinick 1992: 4-5). Those at the top of the distribution often enjoy inordinate power and are able to not only limit redistribution, but shape the rules of the game in favor of those with more resources (Stiglitz 2012). Various studies have found legislative bodies to be more responsive to affluent constituents than to non-affluent constituents (Bartels 2008; Gilens 2012; Volscho and Kelly 2012).

Inequality, especially in its extreme form of poverty, does in the end deprive us of our capabilities, which is said to be a kind of freedom. To the extent that individuals at the bottom of the income distribution could be said to be poor, poverty deprives individuals of their capabilities. Therefore, there is a strong case to be made for judging individual advantage in terms of the capability that a person has — “the substantive freedoms he or she enjoys to lead the kind of life he or she has reason to value” (Sen 1999, p.87). Such freedoms are the basis of individual autonomy. Those with more resources may be better positioned to pursue their goals and objectives, while those with fewer resources may find that their ability to pursue their goals and objectives are limited.

An individual’s ability to pursue their goals and objectives is important to democracy for yet another reason. A democracy, especially as its legitimacy and power are derived from popular consent, assumes that individuals have the capacity to reason for themselves, i.e. to deliberate in the public square, and to act on that capacity in a responsible manner. They cannot effectively participate, whether it be in full policy discussions or selecting their own representatives, if they cannot deliberate in a rational manner. As democracy requires that individuals execute their agency, human agency must be protected. But this human agency also presupposes that basic material needs will have been met, which may be less likely given ever widening disparities in wealth and income. Democracy also requires a measure of trust between people, and growing income inequality is said to threaten trust as various groups, mainly those at the bottom, experience political alienation and perceive the system not to be fair. As social capital is the glue that holds society together (Stiglitz 2012), if individuals believe that the economic and political system is unfair, the glue does not work and society does not function well. This is because institutions effectively promote trust. A trusting population tends to be more cooperative, and governments with trusting populations tend to be less corrupt and function with less conflict and greater responsiveness (Uslaner 2008).

Impact of Inequality on Civic Participation

Income inequality not only distorts democracy in terms of how institutions and political actors respond to different levels of income, but it may have a profound effect on the development of social capital, which affects civic engagement. Democracy requires the active participation of citizens in the affairs of their communities, which extends beyond mere voting. Underlying social capital is the notion that civic virtue is most powerful when it is embedded in a dense network of social relations. American civil society has been defined by its associative life, in which Americans belong to voluntary organizations. And through these organizations, they participate in the affairs of their communities (Putnam 2000).

In a study of the relationship between income inequality and civic engagement, Levin-Waldman (2013) found that in 2008 individuals in households with different levels of income had different levels of civic engagement. Six measures of civic engagement were considered: daily discussions of politics, daily reading of newspapers — which were intended to speak to one’s knowledge about and interest in politics — involvement in protests, attendance at political meetings, visiting public officials, and participating in civic organizations. Participation was found to be greater on all measures of participation among those in households earning more than $100,000 a year than among those earning less than $30,000. Those at the highest end of the distribution were not necessarily more likely to be engaged than those between $30,000 and $99,999, but those in households between $30,000 to $59,999 were considerably more likely to be engaged than those in households below $30,000. Participation appeared to improve dramatically when one was in a household with income greater than $30,000. These differences alone would suggest that entry into the middle class might result in greater levels of civic participation. Moreover, logistical regressions found that those with higher incomes were more likely to be civically engaged, and that those earning less than a minimum wage were least likely to be engaged.

Aside from the adverse impact that income inequality has on civic engagement, it could also lead to political anomie. As family income inequality increases, those families below the median are further from the social norm than before. Similarly, those at the top of the distribution see a larger gap between themselves and the rest of the population. Families at the bottom of the distribution may end up drifting further from the mainstream, and thus may also experience greater alienation as those with greater resources may come to see them as both more distinct and undeserving. This may also have consequences for how citizens in turn view the potential role and functions of government (Haveman, Sandefeur, Wolfe, and Voyer 2004). Poor people experience greater social alienation because of their tendency to participate less, which means that they may be out of touch with common interests. But participation is also less likely because the alienation coming from social isolation will lead many to the conclusion that there really is no benefit from participation in the common project of which they are part. When resources are unequally distributed, those at the top and the bottom might not see themselves as sharing the same fate. Consequently, they have less reason to trust people of different backgrounds. Where inequality is high, people may be less optimistic about being masters of their own fate. Increasing inequality results in less participation because of declining trust (Uslaner and Brown 2005).

Conclusion

With rising inequality, it ought to be clear that there are serious challenges to democracy. It cannot be predicted with certainty just how disruptive inequality will be to democracy, as this is contingent on the fragility of democracy. In the U.S., we are clearly seeing an erosion in democracy in that elected representatives no longer represent all people equally. Rather there is greater responsiveness to those with resources, especially those contributing to political campaigns. Increasingly those without resources find themselves frozen out. In more fragile democracies, the response is unrest. And even in the U.S. we see some of that with various social protest movements. Although the results of the 2016 national election were not necessarily a response to rising income inequality, they were clearly a response to the larger economic conditions of which rising income inequality has been a symptom. Specifically, voters appeared to be rebelling against political elites who apparently were unable to deliver good job growth with rising wages. Voters chose a candidate who, rhetorically at least, was opposed to open borders and free trade, and were effectively challenging the commitment of elites to globalism — the same globalism that has resulted in the two-tier economy with highly skilled and paid workers at the top and poorly skilled and paid workers at the bottom. It might be a stretch to conclude that the election of Donald Trump represents a desire for authoritarianism. And yet, his critics view him as such, and if the voters were not choosing what they might have thought were authoritarian solutions to economic conditions, they were clearly responding to the very economic conditions that have been the source of rising inequality in recent years.

Notes and References

[i] Dividend income is income from stocks and/or other types of investments.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. 2006. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bachrach, Peter and Aryeh Botwinick. 1992. Power and Empowerment: A Radical Theory of Participatory Democracy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Bartels, Larry M. 2008. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Belman, Dale and Paul J. Wolfson. 2014. What Does the Minimum Wage Do? Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Boix, Carles. 2003. Democracy and Redistribution. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gilens, Martin. 2012. Affluence & Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton and New York: Princeton University Press/Russell Sage Foundation.

Hacker, Jacob S. & Paul Pierson. 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer — And Turned its Back on the Middle Class. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Haveman, Robert, Gary Sandefeur, Barbara Wolfe, and Andrea Voyer. 2004. “Trends in Children’s Attainments and Their Determinants as Family Income Inequality Has Increased.” in Kathryn Neckerman ed., Social Inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Levin-Waldman, Oren M. 2013. “Income, Civic Participation and Achieving Greater Democracy. Journal of Socio-Economics. 43,2:83-92.

Meltzer, Alan H. and Scott F. Richard. 1981. “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government.” Journal of Political Economy. 89,5: 914-927.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2012. The Price of Inequality. New York: W.W. Norton.

Uslaner, Eric. 2008. “The Foundations of Trust: Macro and Micro.” Cambridge Journal of Economics. 32:289-294.

—————– and Mitchell Brown. 2005. “Inequality, Trust, and Civic Engagement.” American Politics Research. 33,6 (November):868-894.

Volscho, Thomas W. Jr. and Nathan J. Kelly. 2012. “The Rise of the Super-Rich: Power Resources, Taxes, Financial Markets, and the Dynamics of the Top 1 Percent, 1949-2008.” American Sociological Review. 77,5:679-699.

Zetterbaum, Marvin. 1987. “Alexis De Tocqueville.” In Leo Strauss and Joseph Cropsey eds., History of Political Philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

The Greatest Reshuffle of Individual Incomes since the Industrial Revolution

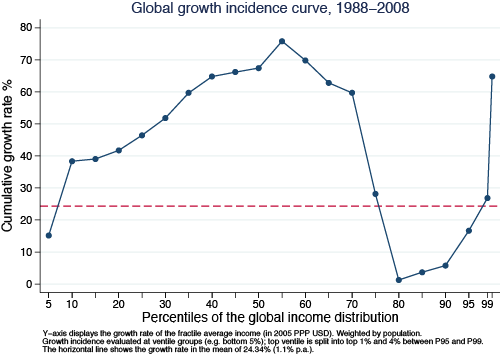

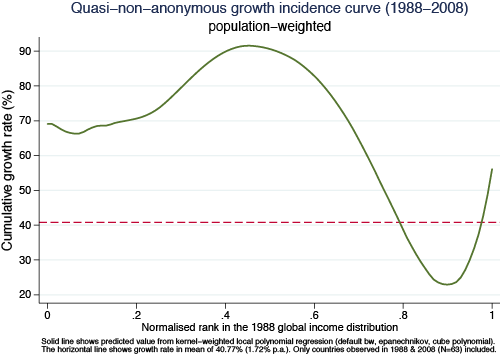

The effects of of globalization on income distributions in rich countries have been studied extensively. This column takes a different approach by looking at developments in global incomes from 1988 to 2008. Large real income gains have been made by people around the median of the global income distribution and by those in the global top 1%. However, there has been an absence of real income growth for people around the 80-85th percentiles of the global distribution, a group consisting of people in ‘old rich’ OECD countries who are in the lower halves of their countries’ income distributions.

The effects of trade, or more broadly of globalization, on incomes and their distribution in the rich countries have been much studied, beginning with a number of works on wage distributions in the 1990s, to more recent papers on the effects of globalization on the labour share (Karabarbounis and Neiman 2013, Elsby et al. 2013), wage inequality (Ebenstein et al. 2015), and routine middle class jobs (Autor and Dorn 2010).

In joint work with Christoph Lakner (Lakner and Milanovic 2015) and in a recently published book, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (Milanovic 2016), Milanovic take a different approach of looking at real incomes across the world population. This is made possible thanks to the data from almost 600 household surveys from approximately 120 countries in the world covering more than 90% of the world population and 95% of global GDP. Since household surveys are not available for all countries annually, the data are ‘centred’ on benchmark years, at five-year intervals, starting with 1988 and ending in 2008. I report the results for up to 2011 in Milanovic (2016), while Lakner has an unpublished update for 2013. The updates confirm, or reinforce, the key findings for 1988-2008 that I discuss here.

The advantage of a global approach resides in its comprehensiveness and the ability to observe and analyze the effects of globalization in many parts of the world and on many parts of the global income distribution. While the true or putative effects of globalization on working class incomes in the rich world have become the object of fierce political battles – especially in the wake of the Brexit vote and the rise of Donald Trump to political prominence in the US – the overall effects of globalization on the rest of the world have received less attention, and when they have, were studied separately, as if independent, from the effects observed in the rich word.

Figure 1 – dubbed by some ‘the elephant graph’ because of its shape – shows real income gains realized at different percentiles of the global income distribution between 1988 and 2008. Income is measured in 2005 international dollars and individuals are ranked by their real household per capita income. The results show large real income gains made by the people around the global median (point A) and by those who are part of the global top 1% (point C). It also shows an absence of real income growth for the people around the 80-85th percentile of the global distribution (point B).

Who are the people at these three key points? Nine out of ten people around the global median are from Asian countries, mostly from China and India. Their gains are not surprising, given that Chinese and Indian GDP per capita has increased by 5.6 and 2.3 times, respectively, over the period. Thus, for example, the person at the median of the Chinese urban distribution in 1988 was then also at the global median, but rose to the 63rd global percentile in 2008 and was above the 70th percentile in 2011. She thus leapfrogged, in terms of income, some 1.5 billion individuals. Such dramatic changes in relative income positions, over a rather short time period, have not occurred since the Industrial Revolution two centuries ago.

The people around the global median are, however, still relatively poor by Western standards. This emerging ‘global middle class’ is composed of individuals with household per capita incomes of between 5 and 15 international dollars per day. To put these numbers into perspective, one should recall that the national poverty lines in rich countries are often higher than 15 dollars per person per day.

The global top 1% is composed overwhelmingly of the people from the advanced economies – one half of the people in that group are Americans, or differently put, 12% of Americans are part of the global top 1%. China and India have many billionaires (in effect, according to the 2015 Forbes list, China and India have more than 300 billionaires versus more than 500 for the US), but compared to the ‘old rich’ world, Asian countries still do not have sufficient numbers of ‘comfortably rich’ or affluent households. In 2008, the threshold for being in the global top 1% was 45,000 international dollars per person per year which, translated into a traditional family structure of two partners and two children, implies an after-tax income of $180,000 (or, using the approximate tax rates of the rich countries, a before-tax income of more than $300,000).

The point that attracts most attention is B. Seven out of ten people at that point are from the ‘old rich’ OECD countries. They belong to the lower halves of their countries’ income distributions, for in effect the rich countries’ income distributions start only around the 70th percentile of the global income distribution. (For some especially rich and egalitarian advanced economies, that start-up point is even higher – Denmark’s distribution begins around the 80th global percentile.)

The contrast between the unambiguous success of people at point A and the relative failure of people at point B allows us to look at the effects of globalization more broadly. Not only can we see them more clearly when thus juxtaposed, but it enables us to ask whether the two points are in some sense related: is the absence of growth among lower middle classes of the rich world the ‘cost’ paid for the high income gains of the national middle classes in Asia? It is unlikely that one can provide a definitive answer to that question, since establishing causality between such complex phenomena that are also affected by a host of other variables is very difficult and perhaps impossible. However, the temporal coincidence of the two developments and the plausible narratives linking them, whether made by economists or by politicians, make the correlation in many people’s mind appear real.

In addition to looking at the global reshuffle of income through the nation-state lenses (are the ‘losses’ of UK working class related to the gains of the Chinese?), we can look at it through a purely cosmopolitan lens where all individuals are treated equally, and the same-percentage income gains realized by the poorer people are valued more than those made by the rich. With such a perspective in mind, it would be hard to dismiss the period 1988-2008 (and as our results for up to 2013 confirm, the period all the way to the present) as being one of failure. One could, despite the rising income share of the global top 1%, argue the opposite by pointing to the close to doubling of real incomes realized by some one-fifth of the world population that lies between the 45th and 65th global percentiles. It is their real income growth that has driven the first decline in global inequality since the Industrial Revolution (Milanovic 2016, Chapter 1).

The issue, however, is that such a cosmopolitan approach is a very abstract way to look at the matters of distribution. Most people are concerned with their incomes as compared to their national peers. Milanovic and Roemer (2016) show that what seems a very positive development (that is, lower global inequality) when individuals are assumed to be concerned solely with their absolute incomes becomes much less positive when we also include in their welfare functions a concern with relative positions in national income distributions. Then the dominant feeling across the world, reflecting increasing national income inequalities, becomes one of a relative loss.

The political implications of a global ‘elephant graph’ are being played out in national political spaces. In that space, rising national inequalities, despite being accompanied by lower global poverty and inequality, may turn out to be difficult to manage politically.

References

Autor, D. and D. Dorn (2010), “The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of US labor market”, American Economic Review 103(5): 1553-97.

Ebenstein, A., A. Harrison, M. McMillan and S. Phillips (2014), “Estimating the Impact of Trade and Offshoring on American Workers Using the Current Population Surveys”, Review of Economics and Statistics 96(4): 581–595.

Elsby, M. W. L., B. Hobijn, and A. Şahin (2013), “The Decline of US Labor Share,” paper prepared for the Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, September 2013.

Karabarbounis, L. and B. Neiman (2013), “The Global Decline of the Labor Share”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(1): 61–103.

Lakner, C. and B. Milanovic (2015), “Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession”, World Bank Economic Review 30(2): 203-232.

Milanovic, B. (2016), Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, Harvard University Press.

Milanovic, B. and J. Roemer (2016), “Interaction of global and national income inequalities”, Journal of Globalization and Development, forthcoming.

Introducing Kuznets Waves: How Income Inequality Waxes and Wanes over the Very Long Run

The Kuznets curve was widely used to describe the relationship between growth and inequality over the second half of the 20th century, but it has fallen out of favour in recent decades. This column suggests that the current upswing in inequality can be viewed as a second Kuznets curve. It is driven, like the first, by technological progress, inter-sectoral reallocation of labour, globalization, and policy. The author argues that the US has still not reached the peak of inequality in this second Kuznets wave of the modern era.

In 1955 when Simon Kuznets wrote about the movement of inequality in rich countries (and a couple of poor ones), the US and the UK were in the midst of the most significant decrease of income inequality ever registered in history, coupled with fast growth. It thus seemed eminently reasonable to look at the factors behind the decrease of inequality, and Kuznets famously found them in expanded education, lower inter-sectoral productivity differences (thus the rent component of wages would be equalized), lower return to capital, and political pressure for greater social transfers. He then looked at (or rather imagined) the evolution of inequality during the previous century and thought that, driven by the transfer of labour from agriculture to manufacturing, inequality rose and reached its peak in the rich world sometime around the turn of the 20th century. Thus, he created the famous Kuznets curve.

The Kuznets curve was the main tool used by inequality economists when thinking about the relationship between development or growth and inequality over the past half century. But the Kuznets curve gradually fell out of favor because its prediction of low inequality in very rich societies could not be squared with the sustained increase in income inequality that started in the late 1970s in practically all developed nations (see the long-run graphs for the US and the UK). Many people thus rejected it.

The Upswing in Current Inequality as a Second Kuznets Curve

In a new book (Milanovic 2016), I argue however that we should see the current upswing in inequality as the second Kuznets curve in the modern times, being driven, like the first, mostly by a technological revolution and the transfer of labour from more homogenous manufacturing into skill-heterogeneous services (and thus producing a decline in the ability of workers to organize), but also (again like the first) by globalization, which has both led to the famous hollowing out of the middle classes in the west and to a pressure to reduce high tax rates on mobile capital and high-skilled labour. The elements listed here are not new. But putting them together (especially viewing technological progress and globalization as practically indissoluble, even if conceptually different) and viewing this as part of regular Kuznets waves is new. It has obvious implications for the future, not the least that this bout of inequality growth will peak like the previous one and eventually go down.

But before I address that part, let us consider recent important work done by economic historians such as van Zayden (1995); Nogal and Prados (2013); Alfani (2014) and Ryckbosch (2014), who have documented periods of waxing and waning inequality in pre-modern Europe. The interesting part is that Kuznets cycles in pre-modern societies basically replicate the Malthusian cycles because they take place in conditions of quasi-stationary mean income. The pre-modern Kuznets cycles are not driven by economic factors but by epidemics and wars. Both lead to a decrease in population, an increase in mean income, higher wages (because of labour scarcity) and thus lower inequality, that is, until population growth in a Malthusian fashion reverses all these gains.

Thus, we can observe Kuznets waves over some six or seven centuries of European history. In pre-modern times, they are observable against time because mean income is more or less constant (it is just one point on the x-axis). After the Industrial Revolution, however, we see the waves responding to economic factors (e.g. technological change, transfer of labour), and can plot them as Kuznets thought against mean income. This is shown here in the graphs for the US and the UK (Figure 1 and 2). In addition, I show in my book long-term inequality cycles for Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, Japan, Brazil, Chile, and over a shorter period for China.

While Kuznets’ explanation was focused almost entirely on economic and thus ‘benign’ forces, he was wrong to overlook the impact of ‘malign’ forces (especially wars) that are powerful engines of income equalisation. I find this somewhat puzzling because Kuznets himself, having worked during World War II in the US Bureau of Planning and Statistics, must have noticed how the war led to the compression of income through higher taxation, financial repression, rationing, price controls, and even sheer destruction of physical assets (as in Europe and Japan).

Inequality May Not Be Overturned Soon

Which leads us to the present. How long will the current upswing of the Kuznets wave continue in the rich world, and when and how will it stop? I am skeptical that it will be overturned soon, at least not in the US where I see four powerful forces that keep on pushing inequality up. I will just list them here (they are, of course, discussed in the book):

- Rising share of capital income which is in all rich countries extremely concentrated among the rich (with a Gini in excess of 90);

- Growing association of high incomes from both capital and labour in the hands of the same people (Atkinson and Lakner 2014);

- Homogamy (the educated and the rich marrying each other); and

- Growing importance of money in politics which allows the rich to write rules favourable to them and thus to maintain the inequality momentum (Gilens 2012).

The peak of inequality in the second Kuznets wave should be lower than in the first (when in the UK, it was equal to the inequality level of today’s South Africa) because the rich societies have in the meantime acquired a number of ‘inequality stabilizers’, from unemployment benefits to state pensions.

The pro-inequality trends will be very hard to overturn during the next generation, but eventually they may be – through a combination of political change, pro-unskilled labour technological innovations (which will become more profitable as skilled labor’s price increases), dissipation of rents acquired during the current bout of technological efflorescence, and possibly greater attempts to equalize ownership of assets (through forms of ‘people’s capitalism’ and workers’ shareholding).

Now, these are of course the benign factors that, I think, will ultimately set inequality in rich countries on its downward path. But history teaches us too that there are malign factors, notably wars, in turn caused by domestic maldistribution of income and power of the elites (as was the case in the World War I), that can also do the job of income levelling. But they do it at the cost of millions of human lives. One can hope that we have learned something from history and would avoid this destructive path to equality in poverty and death.

References

Alfani, G (2014), “Economic inequality in the northwestern Italy: a long-term view (fourteenth to eighteenth century)”, Dondena Working Paper No. 61, Bocconi University, Milano.

Alvarez-Nogal, C and L Prados de la Escosura (2013), “The rise and fall of Spain (1270–1850),” Economic History Review, vol. 66(1), pages 1-37.

Atkinson, A and C Lakner (2014), “Wages, capital and top incomes: The factor income composition of top incomes in the USA, 1960-2005”, November version.

Gilens, M(2012), Affluence and Influence, Princeton University Press.

Kuznets, S (1955), “Economic growth and income inequality”, American Economic Review, March, pp. 1-28.

Milanovic, B (2016), Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization, Harvard University Press.

Ryckbosch, W (2014), “Economic inequality and growth before the Industrial Revolution: A case study of Low countries (14th-16th century), Dondena Working Paper No. 67, Bocconi University, Milano.

van Zanden, J L (1995), “Tracing the beginning of the Kuznets curve: western Europe during the early modern period”, The Economic History Review, vol. 48, issue 4, pp. 1-23. November.

Wealth and Income Distribution: New Theories Needed for a New Era

Growth theories traditionally focus on the Kaldor-Kuznets stylised facts. Ravi Kanbur and Nobelist Joe Stiglitz argue that these no longer hold; new theory is needed. The new models need to drop competitive marginal productivity theories of factor returns in favour of rent-generating mechanism and wealth inequality by focusing on the ‘rules of the game.’ They also must model interactions among physical, financial, and human capital that influence the level and evolution of inequality. A third key component will be to capture mechanisms that transmit inequality from generation to generation.

Six decades ago, Nicholas Kaldor (1957) put forward a set of stylized facts on growth and distribution for mature industrial economies. The first and most prominent of these was the constancy of the share of capital relative to that of wealth in national income. At about the same time, Simon Kuznets (1955) put forward a second set of stylized facts — that while the interpersonal inequality of income distribution might increase in the early stages of development, it declines as industrialized economies mature.

These empirical formulations brought forth a generation of growth and development theories whose object was to explain the stylised facts. Kaldor himself presented a growth model which claimed to produce outcomes consistent with constancy of factor shares, as did Robert Solow. Kuznets also developed a model of rural-urban transition consistent with his prediction, as did many others (Kanbur 2012).

Kaldor-Kuznets Facts No Longer Hold

However, the Kaldor-Kuznets stylized facts no longer hold for advanced economies. The share of capital as conventionally measured has been on the rise, as has interpersonal inequality of income and wealth. Of course, there are variations and subtleties of data and interpretation, and the pattern is not uniform. But these are the stylized facts of our time. Bringing these facts centre stage has been the achievement of research leading up to Piketty (2014).

It stands to reason that theories developed to explain constancy of factor shares cannot explain a rising share of capital. The theories developed to explain the earlier stylized facts cannot very easily explain the new trends, or the turnaround. At the same time, rising inequality has opened once again a set of questions on the normative significance of inequality of outcomes versus inequality of opportunity. New theoretical developments are needed for positive and normative analysis in this new era.

What sort of new theories? In the realm of positive analysis, Piketty has himself put forward a theory based on the empirical observation that the rate of return to capital, r, systematically exceeds the rate of growth, g; the famous r > g relation. Much of the commentary on Piketty’s facts and theorizing has tried to make the stylized fact of rising share of capital consistent with a standard production function F (K, L) with capital ‘K’ and labour ‘L’. But in this framework a rising share of capital can be consistent with the other stylised fact of rising capital-output ratio only if the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour is greater than unity, which is not consistent with the broad empirical findings (Stiglitz, 2014a). Further, what Piketty and others measure as wealth ‘W’ is a measure of control over resources, not a measure of capital K, in the sense that that is used in the context of a production function.

Differences between K and W

There is a fundamental distinction between capital K, thought of as physical inputs to production, and wealth W, thought of as including land and the capitalized value of other rents which give command over purchasing power. This distinction will be crucial in any theorizing to explain the new stylized facts. ‘K’ can be going down even as ‘W’ increases; and some increases in W may actually lower economic productivity. In particular, new theories explaining the evolution of inequality will have to address directly changes in rents and their capitalized value (Stiglitz 2014). Two examples will illustrate what we have in mind.

- Consider first the case of all sea-front property on the French Riviera.

As demand for these properties rises, perhaps from rich foreigners seeking a refuge for their funds, the value of sea frontage will be bid up. The current owners will get rents from their ownership of this fixed factor. Their wealth will go up and their ability to command purchasing power in the economy will rise correspondingly. But the actual physical input to production has not increased. All else constant, national output will not rise; there will only be a pure distributional effect.

- Consider the case where the government gives an implicit guarantee to bail out banks.

This contingent support to income flows from ownership of bank shares will be capitalised into the value of these shares. Of course, there is an equal and opposite contingent liability on all others in the economy, in particular on workers — the owners of human capital. Again, without any necessary impact on total output, the political economy has created rents for share owners, and the increase in their wealth will be reflected in rising inequality. One can see this without going through a conventional production function analysis. Of course, the rents once created will provide further resources for rentiers to lobby the political system to maintain and further increase rents. This will set in motion a spiral of increasing inequality, which again does not go through the production system at all — except to the extent that the associated distortions represent a downward shift in the productivity of the economy (at any level of inputs of ‘K’ and labour).

Analysing the role of land rents in increases in inequality can be done in a variant of standard neoclassical models — by expanding inputs to include land; but explaining increase in inequality as a result of an increase in other forms of rent will need a theory of rents which takes us beyond the competitive determination of factor rewards.

Differences in Inequality: Capital Income versus Labour Income

The translation from factor shares to interpersonal inequality has usually been made through the assumption that capital income is more unequally distributed than labour income. Inequality of capital ownership then translates into inequality of capital income, while inequality of income from labour is assumed to be much smaller. The assumption is made in its starkest form in models where there are owners of capital who save and workers who do not.

These stylised assumptions no longer provide a fully satisfactory explanation of income inequality because: (i) there is more widespread ownership of wealth through life cycle savings in various forms including pensions; and (ii) increasingly unequal returns to increasingly unequally distributed human capital has led to sharply rising inequality of labour income.

Sharply rising inequality of labour income focuses attention on inequality of human capital in its most general sense:

- Starting with unequal prenatal development of the foetus;

- Followed by unequal early childhood development and investments by parents;

- Unequal educational investments by parents and society; and

- Unequal returns to human capital because of discrimination at one end and use of parental connections in the job market at the other end.

Discrimination continues to play a role, not only in the determination of factor returns given the ownership of assets, including human capital; but also on the distribution of asset ownership.

- At each step, inequality of parental resources is translated into inequality of children’s outcomes.

An exploration of this type of inequality requires a different type of empirical and theoretical analysis from the conventional macro-level analysis of production functions and factor shares (Heckman and Mosso, 2014, Stiglitz, 2015).

In particular, intergenerational transmission of inequality is more than simple inheritance of physical and financial wealth. Layered upon genetic inequalities are the inequalities of parental resources. Income inequality across parents, due to inequality of income from physical and financial capital on the one hand, and inequality due to inequality of human capital on the other, is translated into inequality of financial and human capital of the next generation. Human capital inequality perpetuates itself through intergenerational transmission just as wealth inequality caused by politically created rents perpetuates itself.

Given such transmission across generations, it can be shown that the long-run, ‘dynastic’ inequality will also be higher (Kanbur and Stiglitz 2015). Although there have been advances in recent years, we still need fully developed theories of how the different mechanisms interact with each other to explain the dramatic rises in interpersonal inequality in advanced economies in the last three decades.1

High Inequality: New Realities and Old Debates

The new realities of high inequality have revived old debates on policy interventions and their ethical and economic rationale (Stiglitz 2012). Standard analysis which balances the tradeoff between efficiency and equity would suggest that taxation should now become more progressive to balance the greater inherent inequality against the incentive effects of progressive taxation (Kanbur and Tuomala,1994 ).

One counter argument is that what matters is not inequality of ‘outcome’ but inequality of ‘opportunity’. According to this argument, so long as the prospects are the same for all children, the inequality of income across parents should not matter ethically. What we should aim for is equality of opportunity, not income equality. However, when income inequality across parents translates into inequality of prospects across children, even starting in the womb, then the distinction between opportunity and income begins to fade and the case for progressive taxation is not undermined by the ‘equality of opportunity’ objective (Kanbur and Wagstaff 2015).

Concluding Remarks

Thus, the new stylised facts of our era demand new theories of income distribution.

- First, we need to break away from competitive marginal productivity theories of factor returns and model mechanisms which generate rents with consequences for wealth inequality.

This will entail a greater focus on the ‘rules of the game.’ (Stiglitz et al 2015).

- Second, we need to focus on the interaction between income from physical and financial capital and income from human capital in determining snapshot inequality, but also in determining the intergenerational transmission of inequality.

- Third, we need to further develop normative theories of equity which can address mechanisms of inequality transmission from generation to generation.2

References

Bevan, D and J E Stiglitz (1979), “Intergenerational Transfers and Inequality”, The Greek Economic Review, 1(1), August, pp. 8-26.

Heckman, J and S Mosso (2014), “The Economics of Human Development and Social Mobility”, Annual Reviews of Economics, 6: 689-733.

Kaldor, N (1957), “A Model of Economic Growth”, The Economic Journal, 67(268): 591-624.

Kanbur, R (2012), “Does Kuznets Still Matter?” in S. Kochhar (ed.), Policy-Making for Indian Planning: Essays on Contemporary Issues in Honor of Montek S. Ahluwalia, Academic Foundation Press, pp. 115-128, 2012.

Kanbur, R and J E Stiglitz (2015), “Dynastic Inequality, Mobility and Equality of Opportunity“, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 10542.

Kanbur, R and M Tuomala (1994), ‘‘Inherent Inequality and the Optimal Graduation of Marginal Tax Rates”, (with M. Tuomala), Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 96, No. 2, pp. 275-282, 1994.

Kuznets, S (1955), “Economic Growth and Income Inequality”, The American Economic Review, 45(1): 1-28.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Piketty, T, E Saez, and S Stantcheva (2011), “Taxing the 1%: Why the top tax rate could be over 80%”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Roemer, J E and A Trannoy (2014), “Equality of Opportunity”, in A B Atkinson and F Bourguignon (eds.) Handbook of Income Distribution SET Vols 2A-2B. Elsevier.

Stiglitz, J E, et. al. (2015) “Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy“, Roosevelt Institute.

Stiglitz, J E (1969), “Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, Econometrica, 37(3), July, pp. 382-397. (Presented at the December 1966 meetings of the Econometric Society, San Francisco.)

Stiglitz, J E (2012), The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, New York: W.W. Norton.

Stiglitz, J E (2014), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, paper presented to the International Economic Association World Congress, Dead Sea, June and forthcoming in Inequality and Growth: Patterns and Policy, Volume 1: Concepts and Analysis, to be published by Palgrave MacMillan.

Stiglitz, J E (2015), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals: Parts I-IV”, NBER Working Papers 21189-21192, May.

Footnotes

1 For early discussions of such transmission processes, see Stiglitz(1969) and Bevan and Stiglitz (1979).

2 Developments in this area are exemplified by Roemer and Trannoy (2014).

Income Inequality and Citizenship: Quantifying the Link

Our level of income is unarguably dependent on where we live in the world. But evidencing this is tricky. This Posting presents a model that explains global income variability using one variable only – where you live. The results suggest that we might want to reassess how we think about both economic migration and global inequality of opportunity.

It is as obvious as it is well known that the world is unequal in terms of individuals’ incomes (e.g. Mohammed 2015). But it is unequal in a very particular way – when split into ‘inequality within countries’ and ‘inequality between countries’, the latter accounts for by far the biggest gap.