Archive

Kopi Dalam Gempuran Perubahan Iklim

Indonesia saat ini merupakan eksportir kopi nomor empat di dunia setelah Brazil, Vietnam dan Kolombia. Ini menunjukkan bahwa kopi sudah memberikan devisa berharga bagi negeri ini. Produksi kopi dalam 12 tahun cendrung menurun dengan laju 0.7% per tahun. Pada tahun tertentu penurunan bisa lebih besar akibat penyimpangan iklim yang cukup ekstrim. Perubahan iklim diperkirakan akan meningkatkan frekuensi dan intensitas iklim ekstrim yang dapat menurunkan panen kopi secara signifikan. Hal yang lebih mengkhawatirkan, kenaikan suhu yang terus terjadi dapat menyebabkan kopi tidak lagi dapat berproduksi dan pada saatnya nanti kita tidak lagi dapat menikmati lezatnya secangkir kopi.

Kopi Indonesia sudah lama terkenal di dunia dengan citarasa yang khas dari setiap daerah penghasil kopi. Kopi Gayo – Aceh, Sidikalang – Sumatera Utara, Pangalengan – Jawa Barat, Kintamani – Bali, Toraja – Sulawesi Selatan, Wamena – Papua, dan kopi dari daerah lainnya di Indonesia memiliki rasa yang berbeda. Keanekaragaman rasa kopi di Indonesia menjadi salah satu daya tarik sehingga penikmat kopi tidak pernah bosan dan selalu mencoba berbagai rasa. Beragamnya rasa kopi dari setiap daerah disebabkan oleh sifat biofisik yang berbeda seperti jenis tanaman dan satwa yang mendiami daerah tersebut.

Kopi yang hidup pada dataran tinggi akan berbeda rasanya dengan kopi dataran rendah. Kopi yang bersimbiosis dengan tanaman hutan akan berbeda rasanya dengan kopi yang berdampingan dengan pohon mangga, durian atau pohon buah-buahan lainnya. Begitu pula interaksi dengan fauna lainnya yang turut berpengaruh. Selain itu tentu saja kondisi iklim juga memberikan dampak terhadap rasa kopi dan produktivitasnya. Kopi tertentu tidak bisa berproduksi atau produksi sangat rendah karena berubahnya kondisi iklim.

Pengamatan di Afrika selama 49 tahun terakhir menunjukkan adanya kenaikan suhu yang cukup konsisten dan menyebabkan penurunan produktivitas kopi yang cukup signifikan yaitu sebesar 46%. Wilayah pertanaman yang sesuai untuk tanaman kopi juga semakin terbatas. Di Indonesia, wilayah pertanaman kopi utama untuk jenis arabika umumnya pada wilayah dengan ketinggian di atas 1000 m d.p.l. sedangkan robusta antara 400-800 m d.p.l.

Upaya adaptasi yang dilakukan petani dengan naiknya suhu udara dan berubahnya pola hujan akibat perubahan iklim ialah mengembangkan wilayah pertanaman kopi baru ke wilayah yang lebih tinggi. Wilayah dengan ketinggian di atas 1000 m d.p.l. umumnya di Indonesia umumnya masih berupa hutan dan berada pada kawasan lindung. Penelitian yangh dilaksanakan oleh Tim peneliti IPB di wilayah Toba, Sumatera Utara, menemukan bahwa sudah banyak petani yang mengembangkan kebun kopinya ke wilayah yang lebih tinggi dan masuk ke wilayah hutan lindung, karena suhu lebih rendah dan masalah hama relatif lebih rendah.

Pada saat ini, sekitar 62% kebun kopi petani di Kabupaten Samosir berada di kawasan lindung. Hasil prediksi yang dilakukan oleh Tim Peneliti IPB, apabila tidak ada upaya pencarian varietas yang lebih adaptif terhadap suhu tinggi, wilayah yang sangat sesuai (‘very suitable’) untuk pertanaman kopi yang sesuai di wilayah Toba akan bergeser ke ketinggian di atas 1500 m d.p.l. Wilayah yang saat ini sangat sesuai untuk tanaman kopi akan menjadi tidak sesuai (unsuitable). Hal ini berarti akan mengancam keberadaan hutan lindung.

Tantangan lain, terjadinya kenaikan suhu akibat perubahan iklim juga akan meningkatkan serangan hama penggerek buah kopi. Pengamatan selama 10 tahun terakhir di wilayah Toba menunjukkan adanya tren kenaikan tingkat serangan hama ini. Hasil proyeksi tim peneliti IPB menunjukkan bahwa tingkat serangan hama penggerek buah kopi akan semakin besar ke depan. Terjadinya kenaikan suhu akan menurunkan lama waktu yang diperlukan untuk menggandakan diri.

Pada saat ini di wilayah pertanaman kopi arabika (ketinggian 700-1500 m d.p,l), waktu yang diperlukan hama penggerek buah kopi untuk menggandakan diri antara 10 sampai 12 hari (hijau), di masa yang akan datang akan lebih singkat, yaitu hanya sekitar 4-5 hari (merah). Dapat dibayangkan semakin cepatnya pertumbuhan populasi hama penggerek buah kopi, maka tingkat serangan hama akan semakin tinggi, dua sampai tiga kali lebih parah dari saat ini dan dapat membuat petani kopi tidak dapat lagi memanen kopinya. Lebih lanjut hasil prediksi tim IPB, penurunan produktivitas kopi akibat perubahan iklim dapat mencapai lebih dari 50%. Tanpa upaya adaptasi, produktivitas kopi pada wilayah pertanaman kopi saat ini tidak akan melebihi 0.5 t/ha.

Prasyarat Internasional

Dunia internasional saat ini semakin menyukai kopi Indonesia. Namum demikian, dunia internasional memiliki prasyarat-prasyarat dalam mengkonsumsi berbagai komoditi termasuk kopi. Perhatian negara-negara Eropa dan Amerika terhadap isu lingkungan akhir-akhir ini semakin besar. Untuk itu kopi Indonesia harus mulai membenahi produksi kopi khususnya pada tahap budidaya dan pasca panen. Negara-negara maju semakin peduli dengan isu deforestasi dan degradasi lahan. Terjadinya perubahan iklim diprediksi akan membatasi wilayah pengembangan kopi ke wilayah yang lebih tinggi yang umumnya berada pada kawasan lindung dan berhutan.

Perilaku budidaya kopi pada daerah lindung dan konservasi dengan karbon tinggi akan berpengaruh terhadap perubahan iklim (PI). Negara-begara Uni Eropah pengimpor komoditas pertanian mensyaratkan bahwa dalam pengembangan kebun atau lahan pertanian tidak menyebabkan terjadinya konversi atau pemanfaatan lahan-lahan yang memiliki cadangan karbon tinggi seperti hutan. Apabila pola pengembangan kebun kopi dengan pemanfaatan atau pembukaan lahan berhutan terus berlanjut maka akan berdampak pada citra kopi Indonesia di mata internasional. Untuk itu dibutuhkan strategi dalam pengembangan dan kajian teknologi sehingga kopi Indonesia lebih adaptif terhadap perubahan iklim dan produksinya meningkat dengan citarasa terjaga, sehingga tetap laku di dunia.

Teknologi Adaptif Iklim untuk Petani Kopi

Beragamnya pengaruh perubahan iklim terhadap tanaman kopi, menimbulkan kekhawatiran banyak Negara penghasil kopi dan sudah barang tentu bagi para pencandu kopi. Hilangnya kopi dengan cita rasa tertentu karena tidak lagi bisa dikembangkan akibat perubahan iklim, sudah menjadi perbincangan dunia. Berbagai media melaporkan bahwa perubahan iklim sudah mengancam kopi. Tanpa ada upaya adaptasi, bukan tidak mungkin dalam 30 tahun ke depan, banyak negara penghasil kopi saat ini tidak lagi bisa berproduksi, bahkan diprediksi 50 tahun ke depan, kita tidak lagi bisa menikmati secangkir kopi karena kopi tidak lagi bisa ditanam karena dengan terjadinya perubahan iklim, tidak ada lagi lokasi yang bisa ditanami kopi.

Oleh karena itu, diperlukan adanya varietas atau jenis kopi yang lebih tahan suhu tinggi, teknologi yang adaptif, tahan terhadap serangan hama dan memiliki produksi yang tinggi. Petani menunggu bimbingan dari parapihak, pemerintah dan ahli kopi. Dari pengamatan lapangan, sebagian besar petani kopi di wilayah Toba masih banyak yang belum menerapkan praktek-praktek budidaya pertanian dan manajemen yang baik. Kegiatan pemangkasan misalnya jarang dilakukan petani, kalaupun ada tidak dilakukan secara kontinu atau bagian-bagian tanaman yang dipangkas tidak menentu, sehingga tanaman menjadi tinggi yang menyulitkan pada saat panen, cabang-cabang meranggas sehingga komposisi antara cabang-cabang bawah, tengah dan atas tidak seimbang dan proporsional lagi.

Kondisi ini menyebabkan umur ekonomisnya menjadi lebih singkat. Penggunaan naungan juga banyak yang belum melakukannya, sementara tanaman kopi sangat memerlukan kondisi ini. Pengendalian hama penggerek buah juga relatif tidak dilakukan dengan baik. Buah yang rusak dan diserang penggerek buah banyak ditinggalkan dibiarkan jatuh di tanah sehingga menjadi sumber makanan bagi hama untuk terus berkembang. Pengelolaan yang baik, ialah dengan memutus siklus hama dengan cara mengambil semua buah yang ada pada tanaman maupun yang jatuh di tanah dan dimusnahkan. Cara pengendalian ini akan efektif apabila dilakukan oleh semua petani dalam suatu hamparan yang sama, kalau tidak hama PBKo hanya akan pindah dari satu kebun ke kebun lainnya. Kurang diterapkannya praktek-prekter pertanian yang baik membuat tanaman kopi semakin rentan terhadap dampak perubahan iklim.

Momentum tingginya permintaan kopi dalam negeri, luar negeri dan persepsi positif masyarakat terhadap kopi yang ditandai dengan maraknya berbagai café-café kopi perlu disikapi dengan melakukan edukasi pada petani kopi. Petani yang terlanjur melakukan budidaya kopi pada areal konservasi dan lokasi yang memiliki stok karbon tinggi diharapkan tidak mengembangkan lagi pada daerah lain dengan kondisi sama. Perlu dicarikan lokasi budidaya kopi berupa daerah terdeforestasi atau stok karbon rendah dan dalam pengembangannya menggunakan tanaman naungan multiguna yang dapat menciptakan kondisi iklim mikro yang sesuai bagi kopi. Namun demikian, pengembangan kebun kopi ke dalam wilayah berhutan tanpa merusak hutannya melalui program perhutanan sosial juga dapat dilakukan.

Prof. Dr. Rizaldi Boer, Direktur Eksekutif CCROM SEAP IPB

Capital, Science, Technology

Understanding the way in which contemporary capitalism—which Samir Amin insightfully characterized as the era of generalized monopolies—organizes productive forces is crucial to grasping both the forms of domination defining imperialism today and the profound metamorphoses that monopoly capital has undergone during the last three decades.1

The concept of general intellect, put forward by Karl Marx, is a useful starting point for the exploration of the organization of productive forces. Let us take the example of one of the most “advanced” innovation systems today: Silicon Valley’s Imperial System. Our analysis seeks not only to reveal the profound contradictions of capitalist modernity, but also to highlight the significant transmutation that today’s monopoly capital is undergoing. Far from acting as a driving force for the development of social productive forces, it has become a parasitic entity with an essentially rentier and speculative function. Underlying this is an institutional framework that favors the private appropriation and the concentration of the products of general intellect.

Capital, General Intellect, and the Development of Productive Forces

Capitalism is characterized by the separation of the direct producers from their means of production and subsistence. This separation broke violently into the embryonic phase of capitalist development with the process that Marx referred to as “so-called primitive accumulation” (more correctly translated as “so-called primary accumulation”). It is not just a foundational process, external or alien to the dynamics of capitalism, but one that reproduces itself over time and is accentuated through new and increasingly sophisticated mechanisms with the advent of neoliberal policies, so much so that David Harvey proposed the category “accumulation by dispossession” in his book The New Imperialism to refer to this incessant phenomenon.2

Importantly, the primal separation of the direct producer that Marx describes in chapters 14 and 15 of the first volume of Capital is only formal. In the early stages of industrial capitalism, even if the direct producers did not own the means of production—which they considered foreign property and an external force of domination—they maintained some control over their working tools in the production process. Thus, the separation was not wholly complete until the appearance of large-scale industry in the second half of the twentieth century, which radically changed the situation. The production of machines by machines—that is, the use of an integrated machinery system, as a totality of mechanical processes distributed in different phases moved by a common motor—gave way to a complete separation between workers and their tools. This brought the optimal conditions for a second and deeper dispossession, relegating labor to a subordinated role in the production process and converting the worker into an appendage of a machine. It is worth mentioning, however, that the use of this metaphor by Marx does not mean that the direct producer is unable to eventually contribute to the attainment of an improvement or a technological innovation. There are several historical examples that account for this possibility.

Nevertheless, in terms of the theory of value, there is a general movement toward the predominance of dead labor, objectified in the machine, over living labor—in other words, the prevalence of relative surplus value in the dynamics of capitalist accumulation. The emergence of machinery and large-scale industry meant that capital managed to create its own technical mode of production as the foundation of what Marx conceives in the unpublished sixth chapter of Capital, volume 1, as the real subsumption of labor under capital; in other words, the “specific capitalist mode of production.” As Marx wrote, “the historical significance of capitalist production first emerges here in striking fashion (and specifically), precisely through the transformation of the direct production process itself, and the development of the social productive powers of labour.”3

This process originated during the second half of the First Industrial Revolution and deepened during the Second Industrial Revolution (1870–1914), where science and technology appear as engines of production, forcing development as the so-called first globalization was occurring. Since then, the growth of capital has been directly associated with the development of production forces and the consequent expansion of surplus value, mainly in the form of relative surplus value. At the same time, this is marked by the continuous increase in the organic composition of capital (the relation between capital invested in the means of production and that invested in the labor force), where “the scale of production is not determined according to given needs but rather the reverse: the number of products is determined by the constantly increasing scale of production, which is prescribed by the mode of production itself.”4 This inherent contradiction in the specifically capitalist mode of production is related, in turn, to (1) the trend of concentration and centralization of capital that accompanies accumulation dynamics and (2) the concomitant tendency toward absolute impoverishment of the working class, in what Marx conceives as the general law of capitalist accumulation:

The greater the social wealth, the functioning capital, the extent and energy of its growth, and, therefore, also the absolute mass of the proletariat and the productiveness of its labor, the greater is the industrial reserve army. The same causes which develop the expansive power of capital also develop the labor power at its disposal. The relative mass of the industrial reserve army increases, therefore, with the potential energy of wealth. But the greater this reserve army in proportion to the active labor army, the greater is the mass of a consolidated surplus population, whose misery is in inverse proportion to its torment of labor. Finally, the greater the growth of the misery within the working class and the industrial reserve army, the greater the official pauperism.5

The trend toward the complete separation of the worker from the means of production is consolidated into what Victor Figueroa described as follows:

The factory offers us the image of a production center that does not demand workers’ awareness or knowledge of the production process.… As if the factory, being itself the result of the productive application of knowledge, demanded for the knowledge to be developed outside and, therefore, independently to the workers it houses, where immediate labor is presumably a mere executor of the progress forged separately by science.6

In Labor and Monopoly Capital, Harry Braverman described this fissure as an essential part of the scientific and technological revolution that detached the subjective and objective content of the labor process.

The unity of thought and action, conception and execution, hand and mind, which capitalism threatened from its beginning, is now attacked by a systemic dissolution employing all the resources of science and various engineering disciplines based upon it. The subjective factor of the labor process is removed to a place among its inanimate objective factors. To the materials and instruments of production are added a “labor force,” another “factor of production,” and the process is henceforth carried on by management as the sole subjective element.… This displacement of labor as the subjective element of the process, and its subordination as an objective element in a productive process now conducted by management, is an ideal realized by capital.7

In the face of these circumstances, derived from the technical and social division of labor inherent to the specifically capitalist mode of production, it is worth asking ourselves: In what way does capital, beyond the immediate work that is deployed in the factory, organize the development of the productive forces? What kinds of workers, universities, and research centers participate in this process? What is the role of the state and other institutions? What role do accumulated social knowledge, basic and applied science play? What types of intangible and tangible products are generated? What are the mechanisms and mediations involved in the transformation of scientific and technological work to productive forces? What kind of profit enters the scene and how does it affect the dynamics of social surplus value distribution, concentration, and centralization of capital?

Although Marx does not explicitly address this issue in Capital except in marginal footnotes, in the Grundrisse’s “Fragment on Machines,” he coined the category of general intellect and made some considerations, in the form of notes, that provide important clues to help us understand the subject.

Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. These are products of human industry; natural material transformed into organs of the human will over nature, or of human participation in nature. They are organs of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified. The development of fixed capital indicates to what degree general social knowledge has become a direct force of production, and to what degree, hence, the conditions of the process of social life itself have come under the control of the general intellect and have been transformed in accordance with it. To what degree the powers of social production have been produced, not only in the form of knowledge, but also as immediate organs of social practice, of the real-life process.8

From this, we can infer that fixed capital, or constant capital, is condensed into past material and immaterial labor (dead labor). Consequently, accumulated social knowledge is objectified in the means of production and becomes an immediate force of production. In other words,

general intellect is a collective and social intelligence created by accumulated knowledge and techniques. This radical transformation of the workforce and the incorporation of science, communication and language within the productive forces has redefined the entire phenomenology of labor and the entire global horizon of production. General intellect means that the general form of human intelligence becomes a productive force in the sphere of global social labor and capitalist valorization. The power of science and technology are put to work.… With the concept of general intellect, Marx refers to science and consciousness in general, that is, the knowledge on which social productivity depends.9

With the advent of the capitalist mode of production, a new and particularly significant division was created between what could be called immediate labor and scientific-technological labor. While the former unfolds in the factory, the latter is carried out separately and under different, although complementary, forms of organization, with both converging in the critical function for capitalist development: the increase of surplus value. If immediate labor is actually subsumed by capital, scientific and technological labor can only be, at best, formally subsumed, becoming what Figueroa calls a workshop of technological progress to distinguish it from the way immediate labor in the factory is organized.10 However, the way general intellect is structured, in its quest to accelerate the development of productive forces, acquires increasingly sophisticated and complex modalities, as in the paradigmatic case of the Silicon Valley Imperial Innovation System.

The growing importance of immaterial work in the production process does not imply a “crisis” of the law of value, as suggested by Antonio Negri.11 Rather, it implies that an increasing proportion of the social surplus value and the social surplus fund captured by capital and the state is redistributed toward activities aimed at promoting the development of productive forces. In other words, immediate labor and scientific-technological labor interweave dialectically to broaden the scope of capital valorization through the deepening of exploitation. In this sense, under the prism of the theory of value, the general intellect contributes to increasing the organic composition of capital with a powerful leitmotif: the appropriation of extraordinary profits, that is, profits greater than the average profit, commonly conceived as technological rents. In this aspect, the Ecuadorian-Mexican philosopher Bolívar Echeverría specifies that there are

two poles of monopoly property to which the group of capitalist owners must acknowledge rights in the process of determining the average profit. Based on the most productive resources and provisions of nature, land ownership defends its traditional right to convert the global fund of extraordinary profit into payment for that domain, in other words, into ground rent. The only property that is capable of challenging this right throughout modern history and has indefinitely imposed its own, is the more or less lasting domain over a technical innovation of means of production. This property forces the conversion of an increasing part of extraordinary profit into a payment for its dominion, in other words, into a “technological rent.”12

It is worth noting that Echeverría brackets the notion of technological rent, associating it with ground rent—or surplus associated with the ownership of a monopolizable good that does not derive from incorporated labor during the production process. Under the new forms of general intellect organization, monopoly capital appropriates profit through the acquisition of patents, without implying investments in the promotion and development of the productive forces, behaving in this sense as a rentier agent.

Unlike immediate labor, the subordination of scientific and technological labor to capital is extremely complex, especially because the value that the scientific and technological labor force incorporates into the production process is not immediately objectified; it is the product and result of social knowledge expressed in the market once new commodities, new production processes, and new ways of organizing and increasing labor productivity are concretized. Pablo Míguez refers to this phenomenon not as “a simple subordination to capital, but an independent relation to labor time imposed by capital, making it increasingly difficult to distinguish working time from production time or leisure time.”13

From the theory of value perspective, the process of valorization of scientific and technological labor is materialized in the production and circulation sphere, but in the distribution sphere of valorized capital, that social surplus value, mediated by intellectual property, is issued in the form of a rent. In this sense, it is important to emphasize the fundamental role held by states in the distribution of social surplus to promote basic and applied science, supporting public and private universities, as well as research centers. The state also contributes to creating institutions and policies that allow for the private appropriation of rent to come out of the general intellect. These institutions become crucial to the dynamics of accumulation and uneven development characterizing contemporary capitalism and imperialism.

The transformation of the general intellect into an immediate productive force, materialized in new commodities and new ways of organizing the labor process, requires the mediation of patents and a patenting system. In the capitalist mode of production, the creation of intellectual property through patents or patenting systems acquires a strategic importance in relation to the control and orientation of productive forces. This becomes a key element both for the private appropriation of products that emanate from the general intellect, and for the organization of innovation systems. In this sense, national and international patent legislations constitute a mechanism that enables the privatization and commodification of common goods, hindering potentially beneficial innovations for society.14 For example,

The legal mechanisms for the private appropriation of scientific-technological labor, with the patent as a nodal part in the restructuring of innovation systems, becomes a basic piece for the withholding of extraordinary profits made possible through global corporate regulation in tune with the imperial State policies.… Hence, international law functions as a core piece of private control of scientific-technological labor through a series of intellectual property and international trade regulatory agreements.15

Following this idea, Míguez argues that, in the context of contemporary capitalism, “intellectual property is reinforced as it is the only mechanism that allows for the private appropriation of increasingly social knowledge in its incessant quest to valorize capital.”16

The development of the productive forces in contemporary capitalism—and the course followed by the general intellect—cannot be understood separately from the contemporary domination of monopoly capital. This hegemonic fraction of capital—ubiquitous in contemporary capitalism—finds its raison d’être in the appropriation of extraordinary profits and technological rents through monopoly prices, among other processes. According to Marx, monopoly appropriation of profit through prices refers to prices that rise above the cost of production and the average profit together, enabling monopoly capital to appropriate a relatively greater portion of social surplus value than the one that would correspond to conditions of free competition.

Another fundamental feature of monopoly capital, as a sine qua non condition for obtaining profits, is its need to maintain lasting advantages over other possible participants in a particular branch or branches where it operates. Such advantages can be natural or artificial, depending on the combination of forms of surplus profit, which, in turn, configure particular monopolistic practices. One of these forms is related to capitalism’s revolutionary development of productive forces, as envisioned by Marx: technological change. In this regard, Joseph A. Schumpeter—far from intending to identify his vision of technological change with that proposed by Marx in Capital—sets forth the existence of a positive relationship between innovation and monopoly power, arguing that competition through innovation or “creative destruction” is the most effective means of acquiring advantages over potential competitors. Furthermore, Schumpeter argues that innovation is both a means of achieving monopoly profit and a method of maintaining it.

It should be noted, however, that in the Marxist conception, there is no mechanical or direct identification of technological change with a positive vision of progress. On the contrary, being governed by the law of value and the necessity of capital to broaden accumulation, technological change does not escape the contradictions of capitalist modernity, which, as Echeverría emphasizes, “leads itself, structurally, by the way in which the process of reproduction of social wealth is organized…to the destruction of the social subject and the destruction of nature where this social subject affirms itself.”17

The appropriation of extraordinary monopoly profits produced by means of intellectual property is accompanied in contemporary capitalism by a profound restructuring of this hegemonic fraction of capital, through a process of hyper-monopolization, where three additional forms of profit appropriation stand out:18

- The formation of monopoly capital global networks, commonly known as global value chains, through the geographic expansion of corporate power by transferring parts of production, commercial, and financial service to peripheral countries in search of cheap labor.19 Basically, it is a new nomadism in the global production system based on the enormous wage differentials that persist between the Global North and the Global South (the global labor arbitrage). This restructuring strategy has deeply modified the global geography of production to the degree that just over 70 percent of industrial employment is currently located in peripheral or emerging economies.20

- The predominance of financial capital over other factions of capital.21 In the absence of profitable investments in the productive sphere due to the overaccumulation crisis triggered in the late 1970s, capital began moving toward financial speculation, creating strong distortions in the sphere of social surplus value distribution through the financialization of the capitalist class, which has led to an explosion of fictitious capital—financial assets without a counterpart in material production.22

- The proliferation of extractivism by monopolizing and controlling land and subsoil by monopoly capital.23 In addition to accentuating the dynamics of accumulation by dispossession, the growing global demand for natural resources and energy has led to an unprecedented privatization of biodiversity, natural resources, and communal goods benefiting mega-mining and agribusiness. This implies the appropriation of huge extraordinary profits in the form of ground rent (unproduced surplus value) that translates into greater ecosystem depredation, pollution, famine, and disease with severe environmental implications, including global warming and worsening extreme climatic events that jeopardize the symbiosis between human society and nature.24

The predominance and metamorphosis of monopoly capital under the neoliberal aegis has brought about far-reaching transformations in the organization of production and the labor process. These transformations are integral to the global capitalist system’s geography, leading to a fall of the welfare state, an increase in social inequalities, and the emergence of a new international division of labor, where the labor force becomes the main export commodity. This, in turn, gives way to new and extreme forms of unequal exchange and transfer of surplus from the periphery to the core economies of the system. In this context, the irruption of the technoscience revolution has generated new ways of promoting scientific and technological creativity, of organizing the general intellect on a global scale and of appropriating its products.

Untangling Silicon Valley’s Imperial Innovation System

A strategic dimension of capitalist development in the era of generalized monopolies corresponds to the extraordinary dynamism that the development of productive forces achieves through a rampant rate of patenting. Hence, it is vital to understand the characteristics of the most advanced innovation system today, hegemonized by the United States and georeferenced in Silicon Valley, which operates as a powerful patenting machine and has tentacles in various peripheral and emerging countries. The organizational architecture of the general intellect in this complex economic terrain enables corporate control over scientific and technological labor of an impressive mass of intellectual workers trained in different countries around the world, both in core and periphery economies. In this system, a wide range of agents and institutions interact to speed up the dynamics of innovation, reducing the costs and risks associated with inventors and independent entrepreneurs—organized through innovative embryonic companies known as startups—to be capitalized by large corporations through the acquisition or appropriation of patents.25

Some of the most outstanding features of what we conceive as the Silicon Valley Imperial Innovation System are:

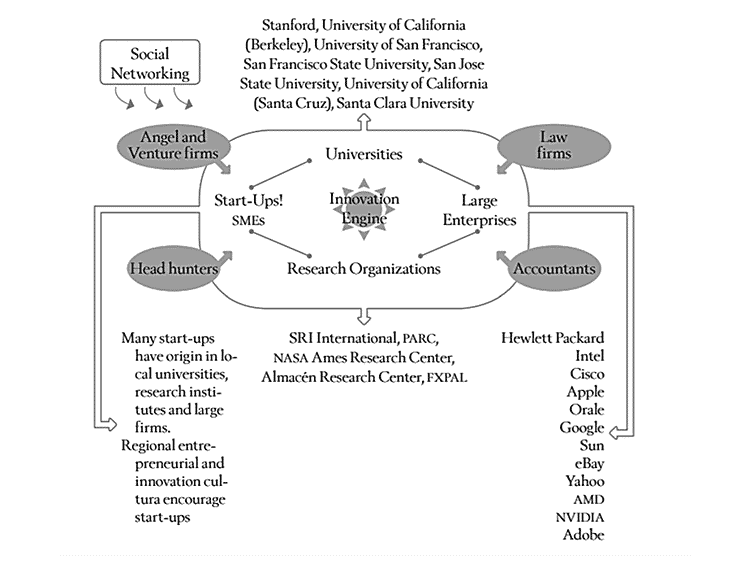

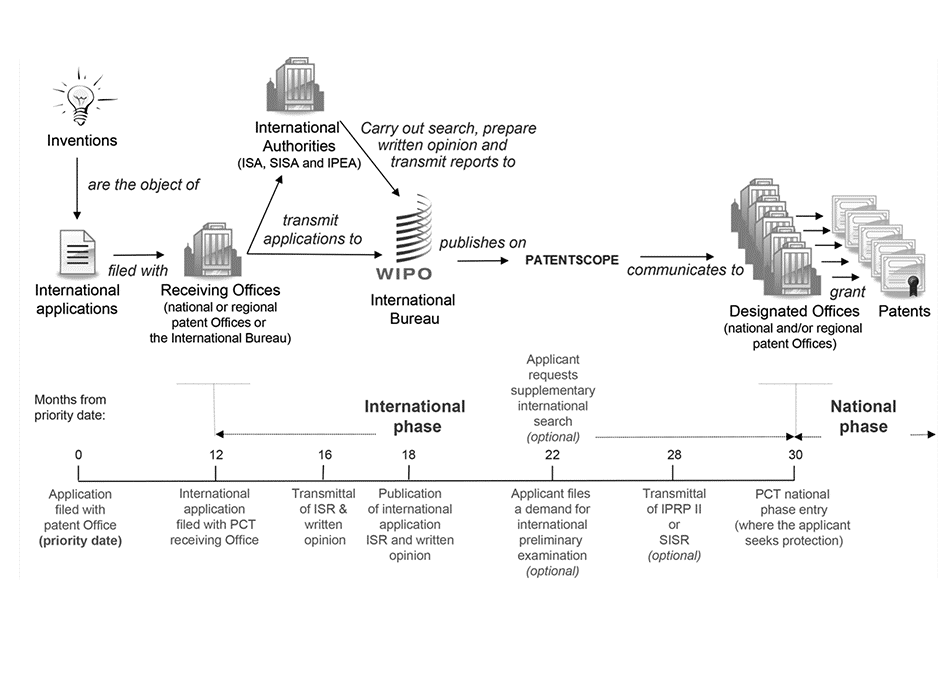

- The internationalization and fragmentation of research and development activities under “collective” methods of organizing and promoting innovation processes: peer to peer, share economy, commons economy, and crowdsourcing economy, through what is known as Open Innovation. These are forms of scientific and technological inventions produced outside the boundaries of multinational corporations, which involve the opening and spatial redistribution of knowledge-intensive activities, with the increasing participation of partners or external agents to large corporations, such as startups that operate as privileged cells of the new innovative architecture, venture capital, clients, subcontractors, head hunters, law firms, universities, and research centers.26 This new form of organizing the general intellect has given way to the permanent configuration and reconfiguration of innovation networks that interact under a complex interinstitutional fabric commanded together by large multinational corporations and the imperial state (see Chart 1). This networked architecture has deeply transformed previous ways of driving technological change. It is worth noting that, in this context, scientific and technological labor carried out by startups is not formally subsumed to capital as inventors are not direct employees of large corporations. Hence, subsumption is subtle and indirect, backed by an institutional framework established by the Patent Cooperation Treaty of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and a sophisticated ecosystem network that fosters the collective development of products emerging as part of the general intellect on a planetary scale and its private appropriation through patents and other proprietary mechanisms mediated by law firms responding to large multinational corporation interests. As a result, accumulated social knowledge—a collective drive accelerated by networks of scientists and technologists—ends up in corporate hands through juridical mechanisms.27

- The creation of scientific cities such as Silicon Valley in the United States and new “Silicon Valleys” recently established in peripheral areas or emerging regions, mainly in Asia, where collective synergies are created to accelerate innovation processes. As Annalee Saxenian highlights, it is a new georeferenced paradigm that moves away from the old research and development models and opens the way for a new culture of innovation based on flexibility, decentralization, and the incorporation, under different modalities, of new and increasingly numerous players that interact simultaneously in local and transnational spaces.28 Silicon Valley became the pivot point of a new global innovation architecture, around which multiple peripheral links are woven to operate as a sort of scientific maquiladora located in regions, cities, and universities around the world. This gives rise to a new and perverse modality of unequal exchange, through which the costs of forming and reproducing a highly skilled workforce involved in the dynamics of scientific innovation are transferred from core economies to peripheral and emerging countries, generating extraordinary profits via monopolistic technological rents.

- New forms of control and appropriation of scientific labor products by large multinational corporations, through various forms of subcontracting, associations, and management and diversification of venture capital. This control is established through a two-way channel. On the one hand, it is established through specialized teams of lawyers thoroughly familiar with the institutional framework and operating rules for patents imposed by the Patent Cooperation Treaty and WIPO, serving the interests of large corporations. Under this complex and intricate regulatory framework (see Chart 2), it is practically impossible for independent inventors to register and patent products on their own. On the other hand, this is done through teams of lawyers who operate as headhunters, contractors, and subcontractors working though “strategic investment” to appropriate and gain control over general intellect products.29

The way in which large multinational corporations participate in the dynamics of innovation incubated and deployed through the Silicon Valley matrix reveals that, more than development driven to facilitate social productive forces, monopolistic capital operates as a rentier agent that appropriates the products of the general intellect without participating in the production process of its development. In other words, the extraordinary profits that constitute the leitmotif of monopoly capital become technological rents in accordance with the meaning that Marx attributes to ground rent: the possibility of demanding a significant portion of social surplus value by virtue of owning a product, in this case the patent, though not acquiring it through a production process that incorporates value through labor. Hence, in the era of generalized monopolies, monopoly capital ceases to be a progressive agent in the development of the productive forces and becomes a parasitic entity that even decides, as owner of intellectual property, which products are potentially significant in the market and which will remain petrified in the freezer of social history.30 - A North-South horizon expansion of the workforce in areas of science, technology, innovation, and mathematics, and increasing recruitment of a highly skilled workforce from the peripheries through outsourcing and offshoring mechanisms. In this sense, highly skilled migration from peripheral countries plays an increasingly relevant role in global innovation processes, generating a paradoxical and contradictory dependence of the South on the North, where patent inventors more often reside in peripheral and emerging countries. In fact, this trend can be seen as part of a higher stage in the development of global value chains—what we prefer to call global monopoly capital networks—as the new international division of labor moves up the value-added chain to the scientific and technological sphere, and while monopoly capital moves to capture profit derived from productivity and knowledge contributed by a highly qualified workforce from the Global South.31 This trend can be found in different sectors of the global economy, including agricultural biotechnology and biohegemony in transgenic crops, as well as the appropriation of Indigenous knowledge related to seed technology.32

Chart 1. Graphic Representation of the Silicon Valley Innovation System

Source: Produced based on information gathered from Strategic Business Insights.

Chart 2. World Intellectual Property Organization Patent Cooperation Treaty

Source: Image adapted from the World Intellectual Property Organization Patent Cooperation Treaty, 2015, http://www.wipo.int.

A key piece that supports the new geopolitics of innovation is the creation of an ad hoc institutional framework aimed at the concentration and appropriation of general intellect products through patents under the tutelage and supervision of the WIPO in agreement with the World Trade Organization (WTO).33 Since the late 1980s, there has been a trend toward generating legislation in the United States, in tune with the strategic interests of large multinational corporations in the field of intellectual property rights.34 Through rules and regulations promoted by the WTO, the scope of this legislation has been significantly expanded. The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative has taken on the role of promoting the signing and implementation of free trade agreements, since intellectual property disputes within the WIPO/WTO tend to be enormously complex due to their multilateral nature. The U.S. strategy also includes bilateral free trade agreement negotiations as a complementary measure to control markets and increase corporate profits. The regulations established by the Patent Cooperation Treaty, amended in 1984 and 2001 within the framework of the WIPO and WTO, have contributed significantly to the strengthening of this trend.

In addition, according to the nature and characteristics of the Imperial Innovation System, the United States appears as the leading capitalist power in innovation worldwide, absorbing 23.9 percent of the total patent applications registered in the WIPO from 1996 to 2018. However, in the same period, China surpassed the United States in patent applications, with 23.1 percent compared to the U.S. 21.7 percent (Table 1).

Table 1. Requested and Granted Patents: Total and 10 Main Countries, 1996–2018

| Patents: Granted | Requested | Distribution (%) | Granted | Distribution (%) | Percent Granted | Rank |

| Total | 45,361,224 | 100.0 | 19,447,764 | 100.0 | 42.9 | |

| Subtotal | 37,412,593 | 82.5 | 15,696,151 | 80.7 | 42.0 | |

| China | 10,497,318 | 23.1 | 3,138,160 | 16.1 | 29.9 | 3 |

| U.S.A. | 9,862,774 | 21.7 | 4,646,826 | 23.9 | 47.1 | 1 |

| Japan | 8,627,834 | 19.0 | 4,093,992 | 21.1 | 47.5 | 2 |

| Korea | 3,534,255 | 7.8 | 1,811,789 | 9.3 | 51.3 | 4 |

| Germany | 1,406,340 | 3.1 | 357,246 | 1.8 | 25.4 | 7 |

| Canada | 842,421 | 1.9 | 388,204 | 2.0 | 46.1 | 6 |

| Russian Federation | 831,702 | 1.8 | 622,539 | 3.2 | 74.9 | 5 |

| India | 652,043 | 1.4 | 130,933 | 0.7 | 20.1 | 13 |

| United Kingdom | 601,246 | 1.3 | 165,056 | 0.8 | 27.5 | 12 |

| Australia | 556,660 | 1.2 | 341,406 | 1.8 | 61.3 | 8 |

Source: SIMDE-UAZ. Estimations using data by WIPO, 1996–2018.

In the era of generalized monopolies, the development of productive forces has entered a point of no return in which the contradictions between progress and barbarism embodied in capitalist modernity have become more evident than ever before. The historical mission of progress attributed to capitalism in the development of the productive forces of society has turned into its opposite: a regressive path that threatens nature and humanity. In this context, the current dispute between the United States and China is uncertain. While there are signs that the United States still maintains leadership in strategic fields of innovation, China has been gaining ground and contesting the U.S. scientific-technological preeminence and global hegemony. Under the conditions of this disputed scenario, the COVID-19 pandemic opens a great question, where the only certainty is uncertainty.

Notes

- ↩ David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- ↩ Karl Marx, chap. 6 in El capital (1867; repr. Mexico: Siglo XXI, 1981), 60.

- ↩ Marx, chap. 6 in El capital, 76.

- ↩ Karl Marx, El capital, tomo 1, vol. 3 (1867; repr. Mexico: Siglo XXI, 2005), 804.

- ↩ Victor Figueroa, Reinterpretando el subdesarrollo: Trabajo general, clase y fuerza productiva en América Latina (Mexico: Siglo XXI, 1986), 40.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Elementos fundamentales para la crítica de la economía política 1857–1858 (Grundrisse), tomo 2 (1858; repr. Mexico: Siglo XXI, 1980), 229–30.

- ↩ Antonio Gómez Villar, “Paolo Virno, lector de Marx: General Intellect, biopolítica y éxodo,” SEGORÍA: Revista de Filosofía Moral y Política 50 (2014): 306.

- ↩ Figueroa, Reinterpretando el subdesarrollo: trabajo general, clase y fuerza productiva en América Latina, 41.

- ↩ Antonio Negri, Marx más allá de Marx (Madrid: Akal, 2001).

- ↩ Bolívar Echeverría, Antología: Crítica de la modernidad capitalista (La Paz: Oxfam, Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2011): 78–79.

- ↩ Pablo Míguez, “Del General Intellect a las tesis del Capitalismo Cognitivo: Aportes para el estudio del capitalismo del siglo XXI,” Bajo el Volcán 13, no. 21 (2013): 31.

- ↩ Guillermo Foladori, “Ciencia Ficticia,” Estudios Críticos del Desarrollo 4, no. 7 (2014): 41–66.

- ↩ Julián Pinazo Dallenbach and Raúl Delgado Wise, “El marco regulatorio de las patentes en la reestructuración de los sistemas de innovación y la nueva migración calificada,” Migración y Desarrollo 27, no. 32 (2019): 52.

- ↩ Míguez, “Del General Intellect a las tesis del Capitalismo Cognitivo,” 39.

- ↩ Echeverría, Antología, 173.

- ↩ Francisco Javier Caballero, “Replanteando el desarrollo en la era de la monopolización generalizada: Dialéctica del conocimiento social y la innovación” (PhD dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Mexico, 2020).

- ↩ Raúl Delgado Wise and David Martin, “The Political Economy of Global Labor Arbitrage,” in The International Political Economy of Production, ed. Kees van der Pijl (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2015), 59–75.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster, Robert W. McChesney, and R. Jamil Jonna, “The Global Reserve Army of Labor and the New Imperialism,” Monthly Review 63, no. 6 (November 2011): 1–15.

- ↩ Walden Bello, “The Crisis of Globalist Project and the New Economics of George W. Bush,” in Critical Globalization Studies, ed. Richard P. Appelbaum and William I. Robinson (New York: Routledge, 2005),101–9.

- ↩ Robert Brenner, The Boom and the Bubble: The U.S. in the World Economy (New York: Verso, 2002); John Bellamy Foster and Hannah Holleman, “The Financialization of the Capitalist Class: Monopoly-Finance Capital and the New Contradictory Relations of Ruling Class Power,” in Imperialism, Crisis and Class Struggle: The Enduring Verities and Contemporary Face of Capitalism, ed. Henry Veltmeyer (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

- ↩ James Petras and Henry Veltmeyer, Extractive Imperialism in the Americas (Leiden: Brill, 2013).

- ↩ Guillermo Foladori and Naina Pierri, ¿Sustentabilidad? Desacuerdos sobre el desarrollo sustentable (Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa, 2005).

- ↩ Raúl Delgado Wise, “Unraveling Mexican Highly-Skilled Migration in the Context of Neoliberal Globalization,” in Social Transformation and Migration: National and Local Experiences in South Korea, Turkey, México and Australia, ed. Stephen Castles, Derya Ozkul, and Magdalena Arias Cubas (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015): 201–18; Raúl Delgado Wise and Mónica Guadalupe Chávez, “¡Patentad, patentad!: Apuntes sobre la apropiación del trabajo científico por las grandes corporaciones multinacionales,” Observatorio del Desarrollo 4, no. 15 (2016): 22–30; Míguez, “Del General Intellect a las tesis del Capitalismo Cognitivo.”

- ↩ Henry Chesbrough, “Open Innovation: A New Paradigm for Understanding Industrial Innovation,” in Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm, ed. Henry Chesbrough, Wim Vanhaverbeke, and Joel West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 1–14.

- ↩ Guillermo Foladori, “Teoría del valor y ciencia en el capitalismo contemporáneo,” Observatorio del Desarrollo 6, no. 18 (2017): 42–47.

- ↩ AnnaLee Saxenian, The New Argonauts: Regional Advantage in a Global Economy (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2006).

- ↩ Titus Galama and James Hosek, S. Competitiveness in Science and Technology (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2008).

- ↩ Foladori, “Teoría del valor y ciencia en el capitalismo contemporáneo.”

- ↩ Raúl Delgado Wise, “El capital en la era de los monopolios generalizados: Apuntes sobre el capital monopolista,” Observatorio del Desarrollo 6, no.18 (2017): 48–58; Rodrigo Arocena and Judith Sutz, “Innovation Systems and Developing Countries” (DRUID Working Paper 02–05, Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics, Aalborg, 2002).

- ↩ Laura Gutiérrez Escobar and Elizabeth Fitting, “Red de semillas libres: Crítica a la biohegemonía en Colombia,” Estudios Críticos del Desarrollo 7, no. 11 (2016): 85–106; Pablo Lapegna and Gerardo Otero, “Cultivos transgénicos en América Latina: Expropiación, valor negativo y Estado,” Estudios Críticos del Desarrollo 6, no. 11 (2016): 19–44; Renata Motta, “Capitalismo global y Estado nacional en las luchas de los cultivos transgénicos en Brasil,” Estudios Críticos del Desarrollo 6, no. 11 (2016): 65–84.

- ↩ Wise and Chávez, “¡Patentad, patentad!”

- ↩ Peter Messitte, “Desarrollo del derecho de patentes estadounidense en el siglo XXI. Implicaciones para la industria farmacéutica,” in Los retos de la industria farmacéutica en el Siglo XXI: Una visión comparada sobre su régimen de propiedad intelectual, ed. Arturo Oropeza and Víctor Manuel Guízar López (Mexico: UNAM–Cofep, 2012),179–200.

The Impact of Covid-19 on the Global Economy

The Covid-19 pandemic has triggered the sharpest and deepest contraction of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) in the history of capitalism as globalisation has gone into reverse. International supply chains, which were once the exemplars of organised production and the backbone of trade, have collapsed; an emphasis on the national economy is back. Overseas travel and tourism have almost stopped entirely. Within the last few weeks, tens of millions of workers have become unemployed and millions of small businesses and their suppliers have closed down. In Europe, the banks, railways, airlines, airports, hotels, restaurants, and pubs are on the verge of bankruptcy. The global financial markets have been plunged into turmoil, share prices have collapsed, and foreign capital investment has halted. Oil prices have crashed on international markets as demand for crude evaporates. This fall has been exacerbated by an inopportune price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Although some countries are now beginning to move slowly towards easing lockdown restrictions the effects of the pandemic have already destroyed the livelihoods of many and have damaged the prospects for future growth. Key components of globalisation have either ceased to function properly or have disappeared completely.

The world’s highest official coronavirus death tolls have been seen in two countries, namely the United States and the United Kingdom. This was unexpected because both of these countries had time to prepare after warnings from scientists and cautionary examples from China and Italy. Moreover both countries have a strong research base, access to vast resources, and millions of scientists, engineers, and medical professionals, yet were still unable to deal with the pandemic effectively.

Global Economic Crisis

The question is how bad will the downturn become? And how soon will the economic recovery begin? Will the recession be double dip, also known as W-shaped downturn, i.e., drop twice before it recovers to its previous growth rate, or more like an L-shaped scenario, otherwise known as a ‘depression’ i.e., a deep recession with no recovery for several years, just as Japan witnessed since the early 1990s (Siddiqui, 2015a). All indicators tell us so far that the crisis is going to deepen and will most likely resemble the L-shaped scenario. We should not expect a return to business as usual.

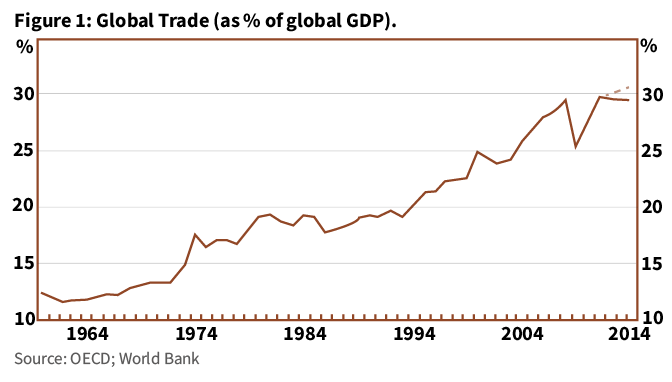

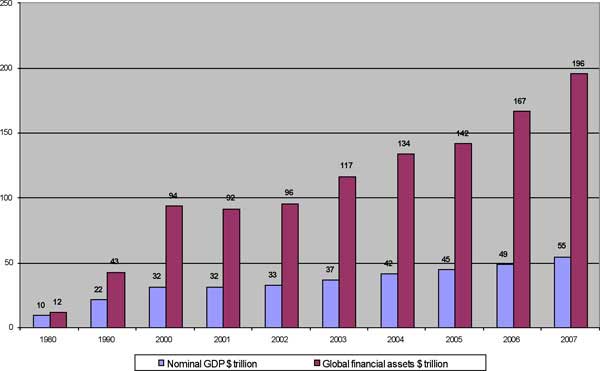

Last week the IMF (International Monetary Fund) warned that the world economy is facing its worst recession since the ‘Great Depression’ of the 1930s with output likely to fall sharply by as much as 6.5% in 2020. Gita Gopinath, the IMF’s chief economist, said the crisis could knock US$ 9 trillion (£7.2 trillion) off global output within the next two years. (See Figure 1 and Figure 3) For all of us who lived through the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, these warnings will bring back stark memories of currency crashes, property prices tumbling and millions out of work and the wealth that was built up in decades disappearing in a matter of months. The covid-19 pandemic economic crisis will be even worse – our generation’s Great Depression.

The IMF says governments must help these households and firms survive because the impact of the coronavirus will be “severe, across the board and unprecedented”. The IMF also predicts that the annual growth of the emerging economies will fall sharply. (see Figure 3) The Fund said this scenario could trigger a downward spiral in heavily-indebted economies. It said investors might be unwilling to lend to some of these nations, which would push up borrowing costs. In fact, only a few countries in the world have that sort of financial power to deal with this. Many are grappling with huge populations, limited financial resources, and the very real possibility of political instability as their people get sick, hungry or both.

The US economy is expected to contract around 6% by the end of this year (Siddiqui, 2019a), which is its biggest decline since 1929 and an evaporation of 30% of aggregate demand over the next three months is anticipated. However, a quick return to work could lead to an increase of number of deaths in the US, with little or no reversal in these projected economic outcomes.

To understand the adverse impact of the corona pandemic on the economy, we need to analyse its effect on different industries. Consumption makes up 70% of the US GDP, but consumption has dropped as businesses close and as households postpone about major purchases as they worry about their finances and their employments. In the US, investment makes up 20% of GDP, but businesses are postponing future investment as they wait for full picture of the corona. Tourism music, sports, entertainment, and restaurants constitute 4.2% of GDP. With restaurants and film theatres are closed and the manufacturing sector constitute nearly 11% of the GDP, but most of this is now disrupted, because global supply chains industries and companies have shut down in anticipation of reduced demand.

According to the IMF forecast, the US economy will shrink by almost 6% this year, compared with a contraction of about 7% in the EU countries and 5% in Japan, while the other experts estimated an annualised second-quarter decline in the US could be as much as 40%. However, if the government were not spending several trillion US dollars to keep businesses afloat, wages to unemployed and benefits to poor sections of the society, the damage would be worse. Over six weeks has passed since national lockdown was declared in UK to limit the spread of Covid-19, during which time it has become clear that the country is also heading for its deepest recession since the ‘Great Depression’.

The US and UK governments have pumped trillions of dollars into their economies and have reduced interest rates to combat recession. For instance, the UK government has launched a job retention scheme to pay up to 80% of the workers’ wages. Nearly 400,000 companies have applied to pay nearly 3 million people through furlough payments, which have cost the UK government £2 billion until now. There is also a similar scheme to compensate five million self-employed workers. Unfortunately, many millions will not be covered under such plans. For businesses, the government has provided up to £300 billion of loans although few of these have so far been awarded by the banks responsible for processing them.

The Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) has predicted that the pandemic crisis could cause a 35% fall in GDP. In fact the economic loss depends on the length of lockdown measures. If lockdown lasts for three months, then GDP will shrink by 13% for 2020. The OBR also predicted more than 2 million people could lose their jobs. David Blanchflower, a former Bank of England rate-setter, has predicted 6 million job losses (i.e. 21% of the workforce). The budget deficit will rise to an unprecedented level and could reach £273 billion by the end of 2020, which is nearly 14% GDP.

The impact of the virus and lockdown has been very different across industries and parts of the UK. Tourism, hotels, restaurants, entertainment, and transport are among the long list of sectors which have been hardest hit by this pandemic. Furloughing is also relatively higher in the North East of England and in London, and South-East England. These current economic variations highlight the need for recovery policy which takes account of local socio-economic needs. Corona pandemic has highlighted the importance of skills. Over decades, in the UK the neoliberal policies, including austerity and over-reliance on the market have proved to be ineffective. But currently millions are facing unemployment, the government need to find ways of help people to find jobs.

The South European countries namely Greece, Italy and Spain, could see their economies contract by as much to 9-10 percent by next spring, while unemployment rates could reach as high as to 19-20% (See Figure 2). The Chinese economy is expected to expand only 1.2% by the end of 2020, which is China’s slowest growth since it embarked economic reforms in 1978 (See Figure 3).

Due to the fall in the demand, the factories are stopping to produce and they do not carry out production. As a result, investments decline, there would be another round of reduction in incomes and consumption levels. So, if jobs and incomes collapse, so do consumptions and savings. But, some consumption has to continue, so people withdraw their savings and past deposits from the banks and financial institutions. A vast majority of the workers in the developing countries are working in the unorganised sector and the poor have low incomes and as their incomes stop, their consumption drastically falls. For example, in India at present, the workers who are now migrating from the big cities to their villages where they feel that their families will at least get food. This model of uneven development, which forces people to migrate to big cities to find employment, has to be re-examined after the pandemic.

In India, the world’s second largest population faces coronavirus with too little money and too few resources for the needs of its people and economy (Siddiqui, 2019b). A large number of people are facing hunger, unemployed, and complete loss of income (Siddiqui, 2019e). The government money offered to support businesses and workers is insufficient to the task and nearly half of the package of measures consists of things already included in an existing scheme. The Indian government does have 77 million tons of grain in buffer stocks, which means there is plenty available for distribution without risking inflation, but the government is reluctant to distribute food among the poor households.

Once lockdown is slowly lifted in India, the government must put more money into village-based employment programmes so that immigrant workers who have returned to their villages from mega-cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Bangalore and Chennai can find some means of livelihood. Subsidies should also be extended to SMEs, especially those supplying essential goods and services. There is a need to reorient India’s economic growth strategy on the basis of its strong internal market in agriculture, which provides jobs to nearly half the country’s workforce. Agricultural growth has the potential to boost demand and thus employment in other sectors too (Siddiqui, 2018a; also see 2017). A great deal of attention paid to economic growth rates in India in recent years, while the on-going agrarian crisis is being ignored (Siddiqui, 2015b).

During the last two decades the agriculture sector in India has witnessed crisis in such as decline in rates of growth, rising numbers of farmers’ suicides, declining prices of several crops, and a widening gap between the agriculture and non-agriculture sectors. The agriculture sector is experiencing unprecedented crisis with stagnation or declining rural employment growth and as a result, food security and employment opportunities for the rural poor have been eroded. The agriculture sector plays an important role in the Indian economy and its better performance is crucial for inclusive growth. This sector at present contributes only 17% of the GDP, while it provides employment to 57% of the Indian work force (Siddiqui, 2019b).

For successful inclusive growth and development, agricultural growth is a pre-requisite. It is important to implement land reforms, improve institutional credits and increase investment in rural infrastructure, to assist small and marginal farmers and also to diversify the rural economy. Until a level playing field is created across the world, otherwise trade liberalisation in agriculture will simply prop-up developed countries farmers at the expense of farmers in the developing countries like India. The neglect of agriculture in India could and must be reversed through a policy of government remuneration procurement prices along with the use of tariffs to insulate domestic food grain prices from world price fluctuations. Furthermore, planting trees on unused lands could improve the quality of air and the overall environment whilst also providing additional employment opportunities in areas where they are now sorely needed.

At present in India, there is a large stock of foodgrains with the government and also bumper autumn crops are being harvested, which means there no danger of inflation. The levels of inequality are very high in India, and the wealth taxes are non-existence. There is the current low level of India’s tax-to-GDP ratio, then when the recovery begins taxes on the rich has to be raised to mobilise the resources to repay the debts. However, if debt-financed expenditures are not undertaken, then recession will intensify and turns into a depression. Therefore, a large fiscal stimulus is an absolute necessity in the current context and without such a stimulus, the humanitarian crisis would intensify.

In India, as elsewhere, the lockdown has reduced social interaction, leading directly to a fall in output and employment. This measure mitigates the physical impact of disease but exacerbates the economic crisis. Hence, the government must intervene to flatten the recession curve to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic.

The coronavirus was detected last December in China and the world had time to prepare for the pandemic in the manner China had shown to be effective in confronting it. Other East Asian governments, such as Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Vietnam, adopted highly successful policies to fight the spread of Covid-19 without causing massive economic disruption. However, the West refused to learn from these examples and failed to take any strong measures to prepare for and to act against the spread of the coronavirus. The two countries supposedly best prepared for a pandemic, the US and the UK, ranked first and second in the Global Health Security Index, performed poorly and proved incapable of handling a rapidly-developing emergency situation. Eventually, the clear evidence of success in East Asia and also in Germany forced even the most reluctant governments to impose lockdowns and to increase the number of people tested for coronavirus. Even so, testing and personal protective equipment (PPE) remained restricted owing to the lack of strategic stockpiles and national manufacturing capability and therefore health staff were left to cope with excessive workloads without the health and safety provisions they had a right to expect.

Economic Policy Failure?

The bankruptcy of neoliberalism is clearly exposed by vastly different responses to the covid-19 pandemic of the world’s two most economically powerful countries. The US was reluctant to take immediate measures to tackle the pandemic and has seemed confused about the way forward ever since, while China from the beginning gave state institutions full responsibility to contain the virus and took decisive measures that led to a successful outcome, at least in the interim.

This pandemic has proved once again that the neoliberal attitude toward public policy deprives societies of the resilience they need to withstand large-scale disruption. At present the private sector in the advanced and in the developing economies has become supportive, and even desperately enthusiastic, for government spending. The proponents of the free market and opponents of government intervention in economic policy are now pleading for unlimited public spending to support asset prices and to save businesses and the economy.

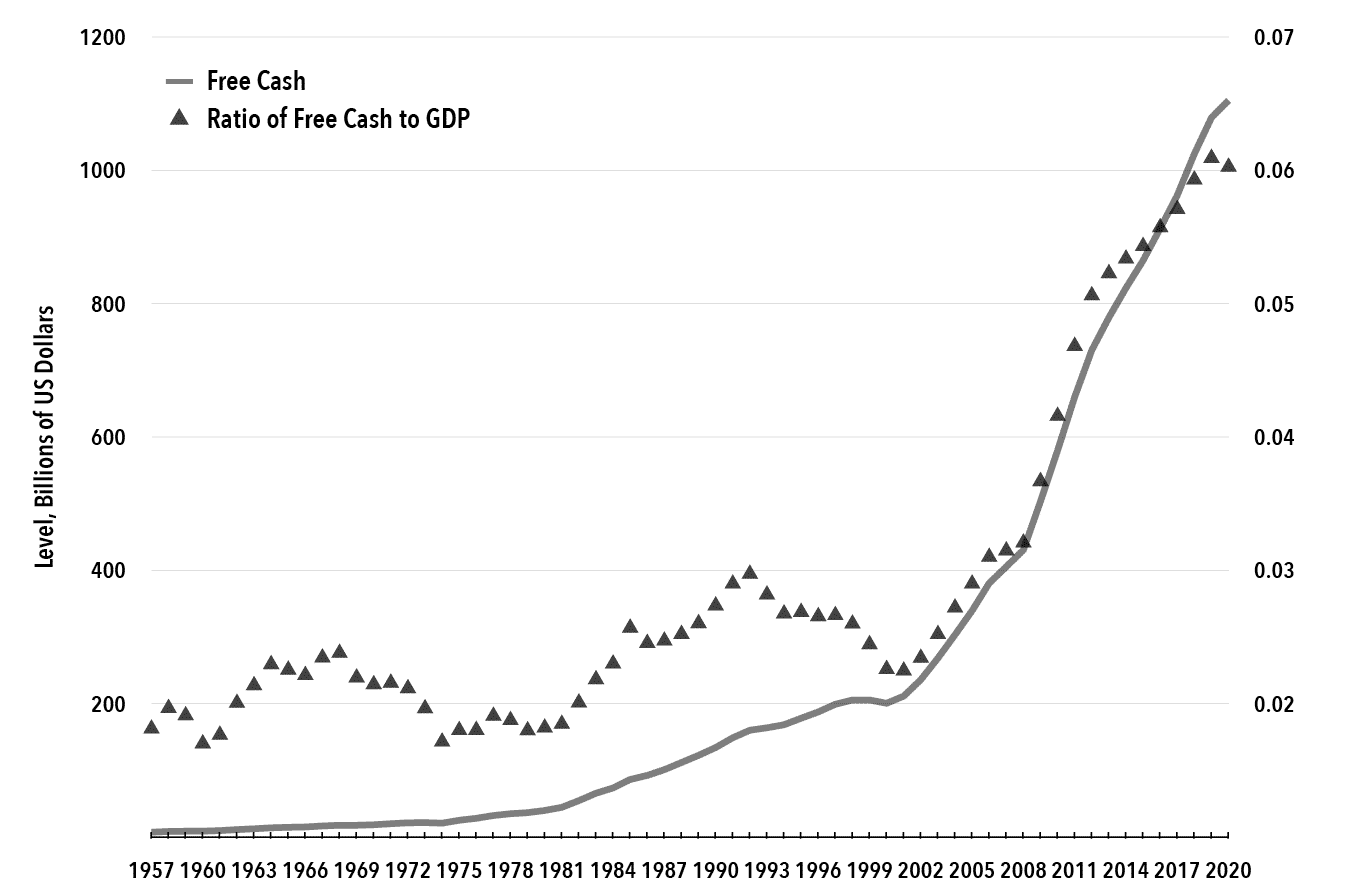

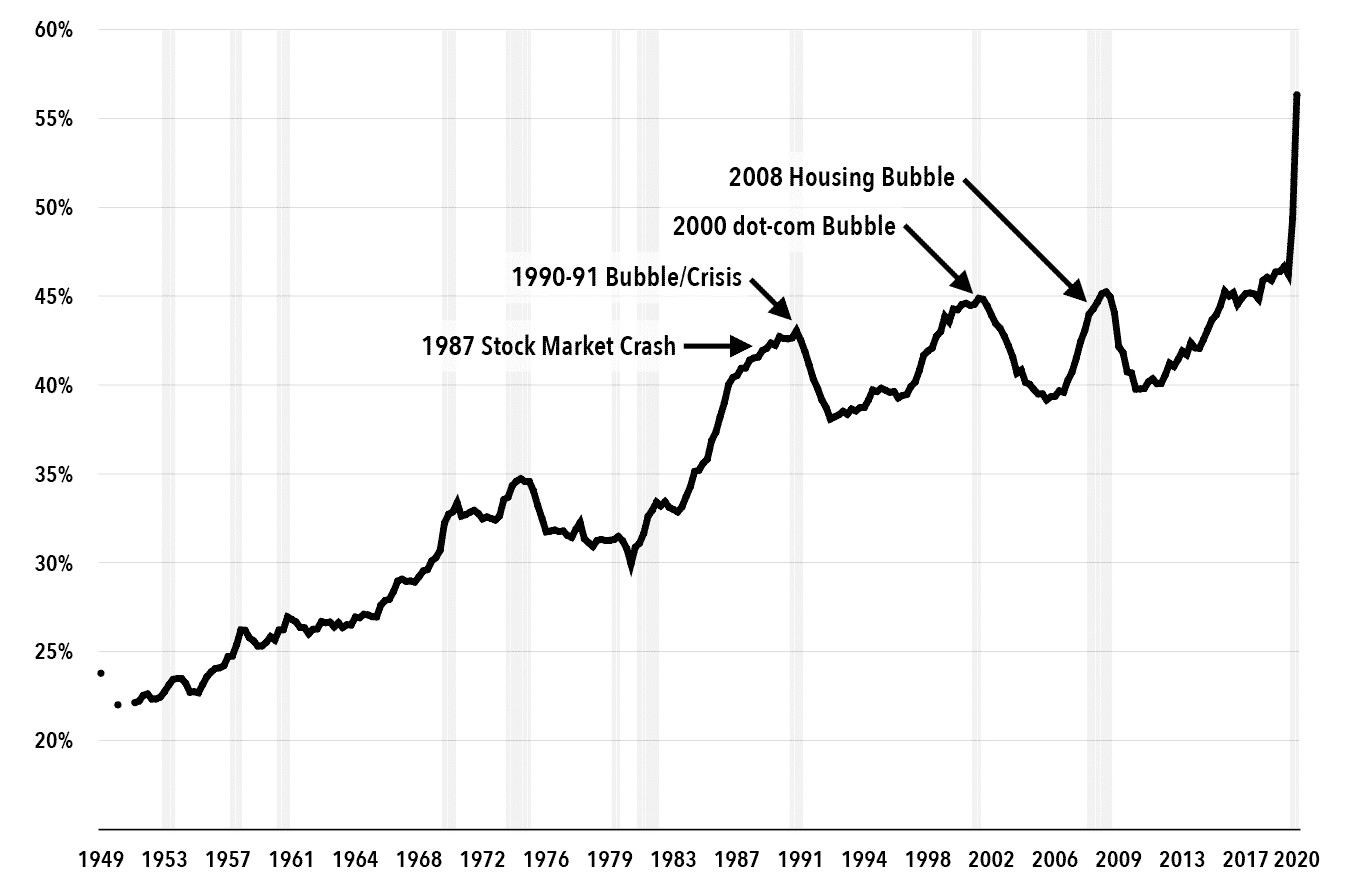

When capitalism faced crisis and a falling rate of profit in the 1980s, it opted for globalisation and the transfer of production from North America, Europe and Japan to take advantage of low wage economies, low regulation, and much higher rates of exploitation available in developing countries (Siddiqui, 2016; also see 2019c). During periods of falling interest rates capitalists compete for financial assets leading to an increase in asset values, which are then used to support further borrowing, more investment in financial assets, which further inflates their value, all without generating any productive economic activity. Consequently, since 2008, productivity across the advanced economies has stagnated and GDP growth has been lower than any decade since 1950 (Siddiqui, 2020a; also see 2020b). At the same time debts have grown enormously, particularly in the developing economies. For example, according to IMF, the total debts of the 30 largest developing economies has reached US$ 72.5 trillion, an increase of 168% in the last ten years.

Around the globe desperate measures are being taken by national governments and international agencies to support the financial system with little provision for ordinary citizens in the developed world and often no provision at all in the developing world. At an emergency submit for the G20 – G7 and emerging economies including China, India, Russia, Brazil, Turkey and Indonesia – on 26th March it was declared that “we are injecting over US$ 5 trillion into the global economy”. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues the rich countries now are planning to pump more money i.e. US$ 9 trillion to help businesses and people to get through the current economic crisis, which is US$ 1 trillion more than announced last month (see Figure 4).

The European Central Bank (ECB) will follow expansionary fiscal policy in the form of deficit spending. Economic expansion is to be backed by Eurobonds. This increased spending will keep business solvent and provide social security measures for workers. The IMF is considering emergency funds for developing countries which could amount to US$ 50 billon. However, these IMF loans are to help with “external financing gaps”, which means they are designed to bail out foreign creditors, not the people of the debtor countries. The harsh terms and conditions that invariably come with these loans will add to the crushing burden on the ordinary people of those countries unlucky enough to receive them.

In early 2020, the world economy was already slowing down, including even the best performing advanced economy, the US. The pandemic hit the economy after nearly four decades of excessive reliance on market forces to achieve greater efficiency. This neoliberalism fostered deindustrialisation and virtual collapse of the manufacturing base, while financial sectors grew to unsustainable proportions (Siddiqui, 2017; also see 2019d). Inevitably, this gross sectoral imbalance left the US and the UK unable to produce enough ventilators and personal safety equipment for their doctors, nurses and care workers.

The pandemic has revealed the pitfalls of capitalist globalization and has restored an understanding of the importance of sovereignty, national economy, and domestic markets. Even so, the potential for cross-border movements of finance has led to further pressure on countries in the developing world to restrict fiscal deficits even in the midst of global economic collapse. As a result the crisis will have a more adverse impact on the lives of the majority of people in Africa, South Asia and Latin America, who have no welfare benefits to protect them, and who rely on incomes drawn from unorganised sectors that have not enjoyed any government support. In addition the exodus of money from developing countries into US dollar dominated assets results in a depreciation of their currencies and thus increases the amount of their overseas debts, which are US-dollar denominated (Siddiqui, 2020a). At least 102 countries have approached the IMF for financial support to deal with the covid-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Capitalism as an economic system is based on individualism, self-interest, greed and competition. It provides optimal conditions for the prosperity of elites on the assumption that the broader population will gain “trickle-down” benefits not otherwise available to them. In the midst of a pandemic in which governments have had to secure employment, incomes, supply chains, and the health system, whilst also supporting the financial system and the wider economy it has become painfully obvious that free trade and markets are incapable of supplying the resilience and core competencies that societies require and their populations demand.

Finally, it seems that Keynesian policies are back after four decades in the wilderness. Key services and utilities must be owned and managed by the government to ensure that basic needs are met and that essential services serve the people rather than profit. Public services must be expanded to create a society based on community, solidarity and respect for nature. Along with such policies, there is also need for progressive taxation so that the putative “wealth creators” who have benefitted from four decades of neoliberalism have the opportunity to contribute fully to the society that has supported them so generously.

Dr Kalim Siddiqui is an economist, specialising in International Political Economy, Development Economics, International Trade, and International Economics. His work, which combines elements of international political economy and development economics, economic policy, economic history and international trade, often challenges prevailing orthodoxy about which policies promote overall development in less developed countries. Kalim teaches international economics at the Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, University of Huddersfield, U.K.. He has taught economics since 1989 at various universities in Norway and U.K.

References:

Siddiqui, K. 2020a. “The US Dollar and the World Economy: A critical review”, Athens Journal of Economics and Business. 6(1): 21-44. January, https:doi:10.30958/ajbe/v6i1.

Siddiqui, K. 2020b. “A Perspective on Productivity Growth and Challenges for the UK Economy”,Journal of Economic Policy Researches 7(1): 1-22.

Siddiqui, K. 2019a. “The US Economy, Global Imbalances under Capitalism: A Critical Review”, Istanbul Journal of Economics 69(2): 175-205, December. ISSN 2602-4151.

Siddiqui, K. 2019b. “The Economic Performance of Modi’s Government in India: The politics of Hindu right”, World Financial Review, July/August, pp. 12-26.

Siddiqui, K. 2019c. “Economic Transformation of China and India: A Comparative Political Economy Perspective”, Asian Profile, 47(3): 243-259.

Siddiqui, K. 2019d. “Government Debts and Fiscal Deficits in the UK: A Critical Review” World Review of Political Economy, 10(1): 40-68, Pluto Journals. DOI: 10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.10.1.0040.

Siddiqui, K. 2019e. “The Political Economy of Inequality and the issue of ‘Catching-up’” World Financial Review, July/August, pp. 83-94.

Siddiqui, K. 2018a. “Capitalism, Globalisation and Inequality”, World Financial Review, November/December, pp. 72-77. ISSN 1756-3763.

Siddiqui, K. 2018b. “U.S. – China Trade War: The Reasons Behind and its Impact on the Global Economy”, The World Financial Review, November/December, pp.62-68. ISSN 1756-3763. http://www.worldfinancialreview.com/?p=36411.

Siddiqui, K. 2017. “Financialization and Economic Policy: The Issues of Capital Control in the Developing Countries”, World Review of Political Economy 8 (4): 564-589, winter, Pluto Journals. DOI: 10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.8.4.0564.

Siddiqui, K. 2016. “Will the Growth of the BRICs Cause a Shift in the Global Balance of Economic Power in the 21st Century?” International Journal of Political Economy 45(4): 315-338, Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Siddiqui, K. “Political Economy of Japan’s Decades Long Economic Stagnation”, Equilibrium Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 10(4): 9-39. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/ EQUIL.2015.033.

Siddiqui, K. 2015b. “Agrarian Crisis and Transformation in India”, Journal of Economics and Political Economy 2 (1): 3-22. ISSN: 2148-8347.

Trade Liberalisation, Comparative Advantage, and Economic Development: A Historical Perspective

I. Introduction

This article critically analyses the theoretical and empirical basis of trade liberalisation and finds that the arguments of many mainstream economists concerning the static and dynamic gains from free trade are based on weak theoretical grounds. I will also discuss here the historical experience of trade liberalised regimes. It also discusses the impact of trade liberalisation on the industrial and agricultural sectors and shows how the performance of both sectors has a long-term impact on local industrialisation, food security, employment and the well-being of people in developing countries.

Global policies under the WTO (World Trade Organisation) are based on what are claimed as universal advantages of open economies and trade liberalisation (WTO, 2013). This paper shows this regime is in fact heavily biased towards the demands of rich and powerful countries and against the needs of developing countries (Reinert, 2007, Rodrik, 2004). Furthermore, this regime undermines elected legislatures and their democratic decision-making processes through constraints imposed by neoliberal treaties and associated mechanisms for the settlement of international disputes. The article further examines the theoretical and empirical basis of trade liberalisation and argues that the claimed benefits of free trade are based on weak grounds. An analysis of free trade in historical perspective highlights its negative implications for future development and suggests that the prosperity of the developing countries could be more dependent on their ability to act in concert to challenge the unbalanced rules-based system of the Western neoliberal order than on their willingness to submit to the strictures of the Bretton Woods institutions and the World Trade Organisation (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012; Sen, 2005).

Free trade theory finds widespread support among the international financial institutions, namely the IMF (International Monetary Fund), World Bank, and WTO (Siddiqui, 2016a). This free trade approach deepens the process of uneven development and unequal exchange as seen, for instance, in the Trump Administration’s attempts to hinder China’s economic development by means of disadvantageous trade agreements. At present, Chinese developmental policies challenge US global corporations such as Boeing and Microsoft because they require some control over the nature of the US investment by granting China a degree of technology transfer. Existing WTO-enforced intellectual property rights, from which US corporations benefit, provide, among many other things, exorbitant patent rights for medicines and grant Microsoft Windows an effective monopoly on operating systems (Siddiqui, 2020a; also see 2018a). With genuine free trade consumers in the US and elsewhere could get cheaper medicines and have more choice in operating systems, but US corporations would not have the levels of profit guaranteed by current arrangements (Siddiqui, 2018a).

II. Late Developers and Free Trade

In the 19th century, Friedrich List in Germany argued for building of the national economy to help the late-developers such as Germany and the US against British imperialism. According to him, due to the historical problems of the late industrialising countries, who were behind in industries and technology compared to Britain and Netherlands and according to him, this could be addressed through strategies of state-led industrialisation and tariff protection (Siddiqui, 2021a).

The List theory was not so much in favour of freedom for colonies and in fact he argued reproducing colonial relations so as a late industrialising country like Germany could become industrially advance and join industrial core of the world economy. The British economy by the second quarter of the 19th century had become imperial economy i.e. industrial-financial centre and its colonies were forced to specialise in the production of agricultural commodities. As Gallagher and Robinson (1953:9) argued that “the British strategy was to transform the colonies into complementary satellite economies, which would provide raw materials and food for Great Britain, and also provide widening markets for its manufacturing.” List advocated that Germany must emulate the British path to industrialisation through protection and government intervention. For example, in the 17th and 18th century England had protected woollen industries by banning exports of raw wool to Netherlands and at the same time concluding treaties to open foreign markets for English products and supported shipping through its Navy.

However, once England secured superiority in industries and technologies, its rulers discovered the free trade doctrine was useful to maintain Britain’s domination. As Reinert (2005: 60) explains: “Britain not only made it politically clear that she saw it as a primary goal to prevent other nations from following the path of industrialization, but also ….possessed an economic theory [in the economics of Smith and Ricardo] that made this goal a legitimate one.” List argued that in order to escape Britain’s domination, Germany should ‘emulate the pragmatism and ruthlessness egoism of the English people’ and by extending support to state-led-industrialisation i.e. protecting infant industries through tariffs and duties on imports. Once competitive edge is acquired by domestic producers then slowly exposes them to foreign competition and resumption of free trade. The list was not in favour of Germany’s isolation but national equalisation and giving later-developers the opportunity to assume a dignified place in the world. However, List did not oppose European colonisation of non-European nations. He advocated that ‘civilised nations’ had to attain ‘balance of the productive powers in industry, commerce and agriculture’ (List, 1983: 51).