Archive

Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession

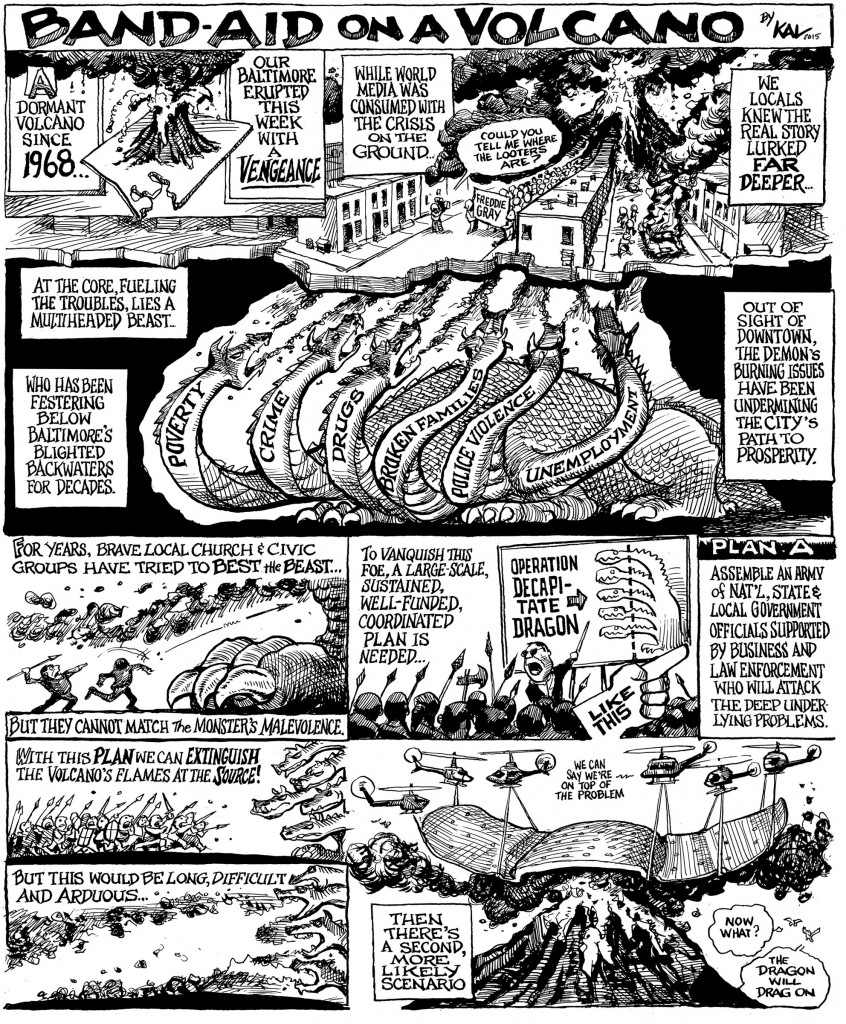

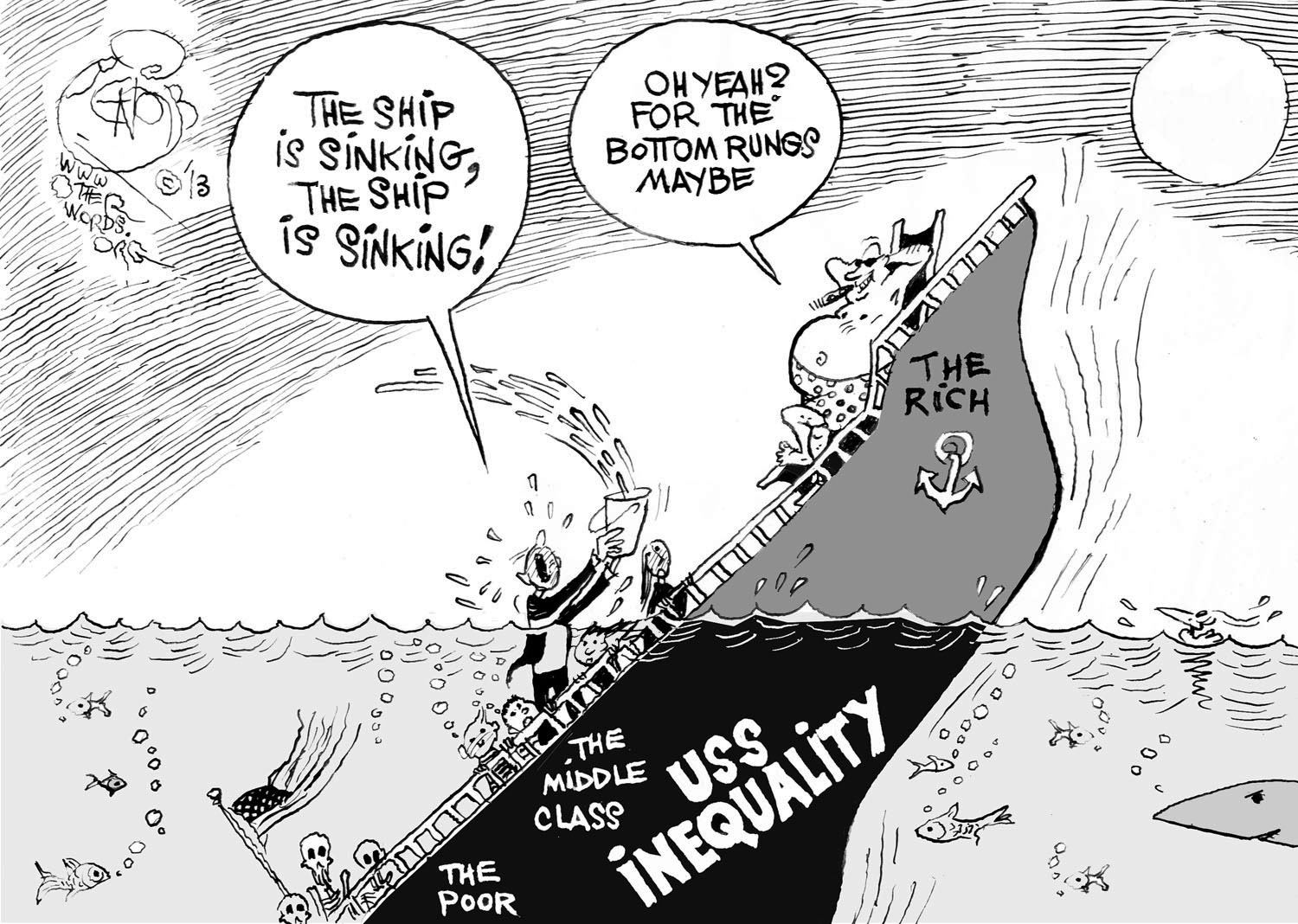

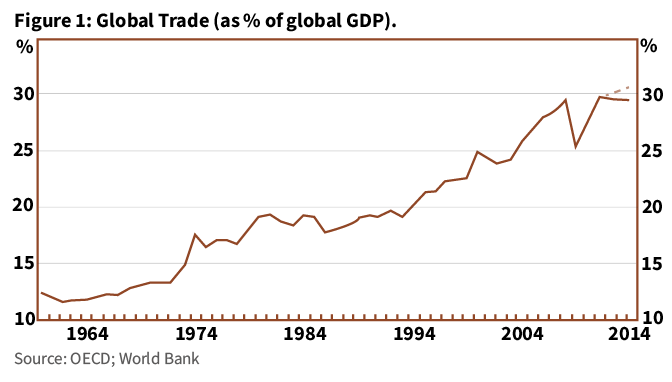

Since 1988, rapid growth in Asia has lifted billions out of poverty. Incomes at the very top of the world income distribution have also grown rapidly, whereas median incomes in rich countries have grown much more slowly. This posting asks whether these developments, while reducing global income inequality overall, might undermine democracy in rich countries.

The period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Great Recession saw probably the most profound reshuffle of individual incomes on the global scale since the Industrial Revolution. This was driven by high growth rates of populous and formerly poor or very poor countries like China, Indonesia, and India; and, on the other hand, by the stagnation or decline of incomes in sub-Saharan Africa and post-communist countries as well as among poorer segments of the population in rich countries.

Anand and Segal (2008) offer a detailed review of the work on global income inequality. In Lakner and Milanovic (2013), we address some of the limitations of these earlier studies and present new results from detailed work on household survey data from about 120 countries over the period 1988–2008. Each country’s distribution is divided into ten deciles (each decile consists of 10% of the national population) according to their per capita disposable income (or consumption). In order to make incomes comparable across countries and time, they are corrected both for domestic inflation and differences in price levels between countries. It is then possible to observe not only how the position of different countries changes over time – as we usually do – but also how the position of various deciles within each country changes. For example, Japan’s top decile remained at the 99th (2nd highest from the top) world percentile, but Japan’s median decile dropped from the 91st to the 88th global percentile. Or, to take another example, the top Chinese urban decile moved from being in the 68th global percentile in 1988 to being in the 83rd global percentile in 2008, thus leapfrogging in the process some 15% of the world population – equivalent to almost a billion people.

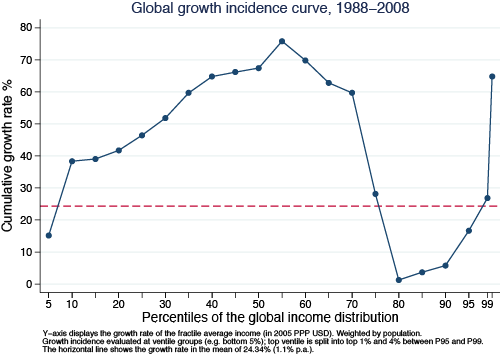

When we line up all individuals in the world, from the poorest to the richest (going from left to right on the horizontal axis in Figure 1), and display on the vertical axis the percentage increase in the real income of the equivalent group over the period 1988–2008, we generate a global growth incidence curve – the first of its kind ever, because such data at the global level were not available before. The curve has an unusual supine S shape, indicating that the largest gains were realised by the groups around the global median (50th percentile) and among the global top 1%. But after the global median, the gains rapidly decrease, becoming almost negligible around the 85th–90th global percentiles and then shooting up for the global top 1%. As a result, growth in the income of the top ventile (top 5%) accounted for 44% of the increase in global income between 1988 and 2008.

Fortunes of income deciles in different countries over time

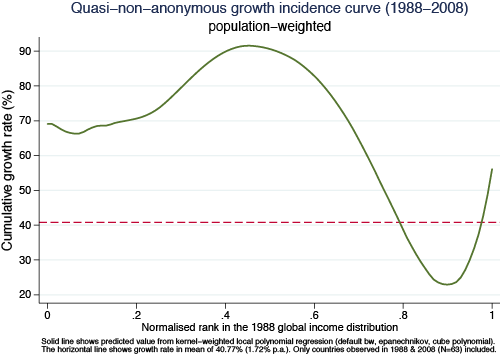

The curve in Figure 1 is drawn using a simple comparison of real income levels at given percentiles of the global income distribution in 1988 and 2008. It is ‘anonymous’ because it does not tell us what happened to the actual people who were at given global income percentiles in the initial year, 1988. In fact, the regional composition of the different global income groups changed radically over time because growth was uneven across regions. A ‘quasi non-anonymous’ growth incidence curve in Figure 2 adjusts for this – the growth rates are calculated for all individual country/deciles at the positions they held in the initial year (1988). The growth rate on the vertical axis (calculated from a non-parametric fit) thus shows how the country/deciles that were poor, middle-class, rich, etc. in 1988 performed over the next 20 years. The supine S shape still remains, although it is now slightly less dramatic.

People around the median almost doubled their real incomes. Not surprisingly, 9 out of 10 such ‘winners’ were from the ‘resurgent Asia’. For example, a person around the middle of the Chinese urban income distribution saw his or her 1988 real income multiplied by a factor of almost 3; someone in the middle of the Indonesian or Thai income distribution by a factor of 2, Indian by a factor of 1.4, etc.

It is perhaps less expected that people who gained the least were almost entirely from the ‘mature economies’ – OECD members that include also a number of former communist countries. But even when the latter are excluded, the overwhelming majority in that group of ‘losers’ are from the ‘old, conventional’ rich world. But not just anyone from the rich world. Rather, the ‘losers’ were predominantly the people who in their countries belong to the lower halves of national income distributions. Those around the median of the German income distribution have gained only 7% in real terms over 20 years; those in the US, 26%. Those in Japan lost out in real terms.

The particular supine S-shaped growth incidence curve (Figure 1) does not allow us to immediately tell whether global inequality might have gone up or down because the gains around the median (which tend to reduce inequality) may be offset by the gains of the global top 1% (which tend to increase inequality). On balance, however, it turns out that the first element dominates, and that global inequality – as measured by most conventional indicators – went down. The global Gini coefficient fell by almost 2 Gini points (from 72.2 to 70.5) during the past 20 years of globalisation. Was it then all for the better?

Probably yes, but not so simply. The striking association of large gains around the median of the global income distribution – received mostly by the Asian populations – and the stagnation of incomes among the poor or lower middle classes in rich countries, naturally opens the question of whether the two are associated. Does the growth of China and India take place on the back of the middle class in rich countries? There are many studies that, for particular types of workers, discuss the substitutability between rich countries’ low-skilled labour and Asian labour embodied in traded goods and services or outsourcing. Global income data do not allow us to establish or reject the causality. But they are quite suggestive that the two phenomena may be related.

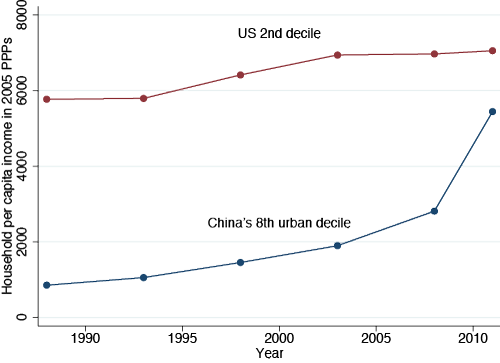

A dramatic way to see the change brought by globalisation is to compare the evolution over time of the 2nd US income decile with (say) the Chinese urban 8th decile (Figure 3). Indeed we are comparing relatively poor people in the US with relatively rich people in China, but given the income differences between the two countries, and that the two groups may be thought to be in some kind of global competition, the comparison makes sense. Here we extend the analysis to 2011, using more recent and preliminary data. While the real income of the US 2nd decile has increased by some 20% in a quarter century, the income of China’s 8th decile has been multiplied by a factor of 6.5. The absolute income gap, still significant five years ago, before the onset of the Great Recession, has narrowed substantially.

Political Implications

And even if the causality cannot be established because of many technical difficulties and an inability to define credible counterfactuals, the association between the two cannot pass unnoticed. What, then, are its implications? First, will the bottom incomes of the rich countries continue to stagnate as the rest of China, or later Indonesia, Nigeria, India, etc. follow the upward movement of Chinese workers through the ranks of the global income distribution? Does this imply that the developments that are indeed profoundly positive from the global point of view may prove to be destabilising for individual rich countries?

Second, if we take a simplistic, but effective, view that democracy is correlated with a large and vibrant middle class, its continued hollowing-out in the rich world would, combined with growth of incomes at the top, imply a movement away from democracy and towards forms of plutocracy. Could then the developing countries, with their rising middle classes, become more democratic and the US, with its shrinking middle class, less?

Third, and probably the most difficult: What would such movements, if they continue for a couple of decades, imply for global stability? The formation of a global middle class, or the already perceptible ‘homogenisation’ of the global top 1%, regardless of their nationality, may be both deemed good for world stability and interdependency, and socially bad for individual countries as the rich get ‘delinked’ from their fellow citizens.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, the movements that we witness do not only lead to an economic rebalancing of the East and West – in which both may end up with global output shares close to what they had before the Industrial Revolution – but to a contradiction between the current world order, where political power is concentrated at the level of the nation-state, and the economic forces of globalization which have gone far beyond it.

References

Anand, Sudhir and Paul Segal (2008), “What Do We Know about Global Income Inequality?”, Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1): 57–94.

Lakner, Christoph and Branko Milanovic (2013), “Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession”, World Bank Working Paper No. 6719, December.

The Uneven and Combined Emergence of “Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics”

The People’s Republic of China’s (henceforth named China) development over the past decades has been nothing short of extraordinary. While undergoing constant transformation and recording the world’s second highest GDP ($) in 2017[1], the socialist past appears a distant memory. Put bluntly, since the start of economic reform in 1978, China is booming with a “unique blend of planned economy and unbridled capitalism”.[2] Meisner even contends that the self-proclaimed Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has evolved to become the guardian of Chinese capitalism.[3] At a glance this may appear as a paradox, due to the apparent zero sum game between communism and capitalism that has been continuously perpetuated by the rhetoric of the Cold War.[4] Conversely, this essay will argue that the emergence of specific ‘Chinese characteristics’ within the country’s manifestation of capitalism, can be understood as an outcome of uneven and combined development (U&CD). Through applying Trotsky’s framework of U&CD to China’s development since 1978, the aim is to show that the Chinese economy is not paradoxical in itself, but rather possesses distinct features which materialized as an amalgamation of pre-existing internal socio-political structures and international influences of Western capitalism. The argument will be structured in the following manner. Firstly, an outline is provided of the advantages that are adherent to the theory of U&CD in explaining the particular elements of Chinese capitalism, followed by a section on the important impact of socialist policies on the peasantry under Mao. Next, the essay shifts focus to Trotsky’s theory of U&CD before applying it to the nexus of 1978. Finally, the argument will be sharpened through detailing some of the precise combinations in the context of labor relations and enterprise management that have resulted from the interaction of China with the global capitalist economy. In sum, this essay will show that conceptualizing China’s economic development through the lens of U&CD allows for a specific understanding of the peculiarities in China’s socio-economic spectrum and ultimately elucidates the allegedly paradoxical synthesis of a self-proclaimed communist party adopting a capitalist mode of production for economic gain.

Challenges in Conceptualizing China’s Development

The rather vague nature of the term ‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics’[5] illustrates the difficulty to conceptualize China’s economic development. The extensive reforms throughout previous decades were far from universal in their implementation and thus, some sectors such as Chinese industry were thoroughly reformed, while privatization of land is still largely impossible.[6] Here, we find both bold restructuring as well as rigid attachment to Maoist policy.[7] Huang uses the terminology ‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics’ to refer to a “factual observation of China’s economic and institutional processes”[8]. His work is a detailed analysis of the elements that constitute the special Chinese characteristics. But as Huang himself implies, his work is an analysis aimed at determining the extent to which China is capitalist.[9] While the insight he develops in his work is very valuable, this paper argues that it largely neglects the dynamics of interaction between domestic and international factors in the shaping of specific particularities within Chinese capitalism. Importantly however, an understanding of the international as a performative element and thus as constitutive of development itself, is essential to any notion of developmental processes.[10] Therefore, in order to investigate the origins of distinctive Chinese characteristics, a different approach is required, which factors in the influence of external forces in the developmental process. This endeavor will be undertaken in the last substantive part of this essay.

Maoist Origins of a Strong Peasantry

Before engaging with the capitalist transformation and the economic reforms after 1978, this section will take a closer look at Maoism and identify special features that laid the basis for later rapid capitalist reform. What was perhaps the most distinguishing trait of Maoism as opposed to Stalinist ideology in the Soviet Union, was Mao’s focus on the peasantry’s revolutionary agency.[11] With the absence of a revolutionary proletarian urban working class, following the effective deindustrialization of the coastal regions by the Japanese invasion, Mao famously declared that the Chinese socialist revolution would be “carried from country to town”[12]. In addition, the Chinese Civil War was fought before the revolution and thus, the latter appears as the conclusion of the former and the initial improvements for peasants could be framed as the success of the CCP.[13] Isaac Deutscher further details that during the 1950s, the state commenced an investment policy, aimed at improving the life-expectancy and literacy of the rural communes.[14] An example is the healthcare available to peasants that was offered under Mao, to counterweigh the rigid constraints on rural-urban migration that will be discussed later.[15] One of the resulting initiatives was the ‘barefoot doctors’ programme, which involved the training of health workers to meet the medical requirements of the peasants.[16] Despite challenging circumstances, the programme was widely considered successful in increasing the prompt availability of cheap healthcare and was acknowledged by the WTO for its positive impact on health levels in rural areas.[17] Overall, the improvements in literacy and healthcare under Mao were unquestionably significant and gave China a distinctive position among in comparison to other developing states.[18] What is important to note is that the high health standards posed a critical factor in the immediate availability of the peasants to take on low wage labour, which in turn was a primary reason for the pull that China exerted on foreign industry to invest so quickly, following the reforms of 1978.[19] In short, the origins of China’s ability to instantaneously sustain an ‘army’ of surplus labour can at least partly be traced back to the influence of socialist policies on the peasantry.[20]

The Framework of Uneven & Combined Development

As we have now arrived at the period within which this paper aims to apply the framework of a Trotskyist dynamic of development, a brief introduction to the theory of U&CD is paramount. Leon Trotsky was grappling with a crucial issue when he formulated the basic premises of his theory. Societal development in Russia was drastically diverging from the path that was predicted by Karl Marx and despite the absence of an established bourgeoisie; revolutionary currents in Russia were extremely powerful compared to England, where Marx had anticipated the initial proletarian revolution.[21] On the basis of this observation, Trotsky established two fundamental features of human development. The first of the two is unevenness, which he identifies as the “most general law of the historic process”.[22] Specifically, Trotsky argues that there is an inherent unevenness in development among the various social entities that constitute the world.[23] Secondly, the core dynamic of all human development is the interaction among these uneven formations, which produces particular dialectical developmental trajectories and is therefore a combined form of development and thus, the “key driver of historical development”[24]. Crucially though, combination is not mere repetition by one society of another societies development.[25] Rather, it is the result of an amalgamation of a society’s internal characteristics with external geopolitical pressures and social forces. Moreover, there are two key features that are integral to this procedure. Firstly, Trotsky identified the “privilege of historic backwardness”[26]. In this, he refers to the possibility for a society to skip specific developmental processes by adopting and further enhancing certain features from more ‘advanced’ societies through the aforementioned interaction, thereby accelerating their development.[27] The second factor refers to the social and geopolitical pressure that a more ‘advanced’ society exerts on others through their respective interaction. In turn, this compels a society to accelerate development under said pressure, hence Trotsky labelling this as the “whip of external necessity”[28].

The Conjuncture of 1978

Let us now locate the existing unevenness between China and the so-called advanced capitalist countries (ACCs) of the global economy at the conjuncture of 1978, out of which the powerful ‘whip of external necessity’ arose. Mao’s initial improvements for the rural peasantry that were discussed earlier, quickly faded and the burden of growing international isolation, a devastating famine and the atrocities committed during the totalitarian ‘Cultural Revolution’ became increasingly visible and took their gruesome toll on the Chinese people and the country’s socio-economic structure.[29] Despite the clear focus on heavy industry under Mao,[30] China’s workforce was comprised of about 70% agrarian labor.[31] However, total productivity stagnated and the agricultural output was relatively low, which further aggravated the concern for food security.[32] What added to the urgency of the Chinese situation was the rapid economic development by the so-called East Asian Tigers, all situated in direct proximity to China, thus generating geopolitical pressure as it became clear that China’s economic development was diverging from that of its industrializing neighbors.[33] This also prompted the leadership to acknowledge the necessity of economic reform, which was launched to overcome economic stagnation.[34] There was an explicit sense of importance attached to economic reform among China’s developmental planners, in the sense that “a big effort to catch up [was necessary to] move to the front ranks of the world”.[35] What fostered this visible unevenness and thus the ‘whip of external necessity’ between China and the capitalist countries of the global economy was the fact that at this very same point in time, global markets were at an unprecedented level of openness.[36] Consequentially, disregarding reform, especially in conjuncture with the ‘neoliberal turn’ of the global economy was equated with political and economic decay.[37] Having situated China in an international context, the following section will show how the ‘Chinese characteristics’ of capitalism originated in the process of combined development.

Identifying the Particularities of Chinese Capitalism through U&CD

Davidson argues that China started to experience U&CD most drastically after its incorporation into the global economy in 1978.[38] The analysis by Dunford and Weidong already applies the theory of U&CD to the historical development of China.[39] Yet, this is conducted in a different manner. Rather than searching for specific combinations within China’s economy, their study takes a broader approach and situates China in a wider context of international unevenness. In contrast, the subsequent analysis aims to provide a more specific account of how the internal and external currents formed distinct fusions in China’s economy. Subsequently, this part will examine some specific results of Chinese capitalist development, following the reforms that were initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1978. Having previously established the existing unevenness between the largely agrarian Chinese economy and the so-called ACCs or the surrounding East Asian Tigers, now the aim is to illustrate the peculiarities within Chinese capitalism that emerged as a result of the interaction between internal factors particular to China and external influences of a westernised market; thereby merging into a combined form of development, aligning with the principles of unevenness and combination of U&CD.

Impact of Hukou and Danwei

The first analysis will focus on labour relations with a specific emphasis on the influence of hukou, (the household registration system), as well as the danwei, (traditional urban working units), on the structure of Chinese wage labour. Both the household registration system and the danwei were institutions that were developed as Maoist policy in the 1950s.[40] However, the following section will outline how both customs still remain an important factor in Chinese capitalism and therefore illustrate its combined nature.

The danwei was a publicly owned unit, integral to urban employment because it served as a lifetime employer, provided housing within the compound and was linked to the distribution of benefits, thus being labelled the “provider of iron rice bowls”[41]. Yet, these values are mostly incompatible with those of a market economy, which was introduced through China’s increased adoption of capitalist relations of production after 1978.[42] As a result, economic reform and the increasing influence of global capitalism have fundamentally altered the makeup of Chinese employment and have effectively ended customs such as lifetime employment or the comprehensive multitude of benefits that previously characterised the danwei.[43] Nevertheless, Xie et al. argue that the danwei continue to be influential.[44] This is apparent through their positive impact on workers’ wellbeing, especially in terms of equal earnings.[45] Given that some of China’s privately owned companies have adopted structures similar to those of the danwei,[46] it is plausible to argue that what remains of the danwei, following the marketization of social services, is still a powerful factor in the alignment of the class structure within China’s urban working class. Importantly however, the impact of the danwei is reliant on low labour mobility and thereby directly linked to the hukou system.[47]

Through the use of a hukou, the second unique trait within Chinese labour relations, the state effectively controls where people work or live and is thereby able to monitor and restrict rural-urban migration.[48] Set up under Mao for exactly this purpose, migration control still remains the central feature of today’s hukou system, despite having undergone liberalisation and restructuring during the period of reform.[49] The system encapsulates the administrative power of the state, as the firm restrictions on transferring permanent residence persist.[50] In addition, the results of market reform have led to the commodification of the urban ‘blue stamp’ hukou, which remains under state control but can now be purchased, thus essentially turning the right to move into a market good.[51] Although the possibility of a temporary residence was introduced by the aforementioned capitalist reforms, any commodified mobility within this system privileges workers with the appropriate financial means or desired qualifications.[52] In fact, the Chinese government is seen to favour temporary migration, as this has a lesser impact on the overall social makeup of cities and in addition reduces the necessary infrastructure requirements for workers.[53] What makes the hukou system such a distinct feature of Chinese capitalism is that it upholds a low wage labour force consisting of migrant workers, who are unable to go the route of formal migration and are compelled to take on jobs in precarious conditions.[54] The difficulty of the official transfer of residence and work rights, combined with diminishing prospects for agricultural employment has resulted in the “largest migration in world history” of peasants into the cities.[55] Thus, what emerges as a product of the remaining hukou system, as well as the economic reforms that attempt to create a capitalist labour market, is a vast number of urban migrant workers without residential rights, often referred to as the “floating population”[56]. This practically indefinite resource of labour made extremely low cost manufacturing on such an unprecedented scale possible.[57] Here, we can clearly observe the element of combined development. On the one hand, we find the introduction of a capitalist mode of production based upon large scale low wage labour, influenced by economic reform and interaction with ‘advanced’ capitalist economies. On the other hand, the hukou system eliminates the most fundamental characteristic of capitalism in itself, namely the “personal independence”[58] of the worker, who, through the hukou system is subject to political subordination, regarding their independence to choose where to work or live. What is more, the control exercised by the state extends much further into personal lives through the repressive measures of censorship and surveillance[59], thereby “disciplining the workforce and keeping social conflicts within bounds”.[60] A recent proposal by the Chinese government exemplifies this approach. Newly planned legislation would require all drivers of the taxi service Didi Chuxing to acquire urban residency permits.[61] In general, many of China’s internet titans such as Ali Baba rely on migrant workers to absorb the demand for low wage labour[62], yet the deliberate obstacle of the hukou system pushes migrant workers further into perilous conditions through essentially limiting workers’ freedom of movement within capitalist labour relations.

Organisational Structure of Enterprises

Chinese enterprises have undergone large reforms and restructuring, mainly aimed at increased privatization.[63] However, the most profitable state-owned enterprises (SOEs) remained under state control.[64] Nevertheless, the privatization of state-owned companies is not necessarily anything unique to China. What is more interesting in this case in the shift of organizational structure in Chinese companies, which will be demonstrated in the following. As we will see shortly, Western education of Chinese management has had an impact on the organizational structure of Chinese enterprises and thereby constitutes another example of combined development. The starting point to this process is the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, which left China with a significant lack of trained Chinese mangers and staff to facilitate the technology transfer from the West and Japan that accompanied the open door policy of China toward the global economy.[65] Accordingly, especially during the 1990s, managers of SOEs were encouraged to complete Western-style management degrees and frequently visit companies in the West.[66] In their study, Ralston et al. trace the development of organizational structures in SOEs both before and after economic reform. They claim that prior to reforms, SOEs are generally best characterised by a ‘clan’ and ‘hierarchy’ culture, which implies a workplace environment similar to a family, with superiors acting as mentors and a high regard of loyalty trust and tradition, while upholding strong hierarchical structures.[67] However, they also trace a substantial shift in their comparison and argue that the integration into the word economy has led SOEs to embrace a more ‘market’ oriented organizational structure based on the aim to maximize productivity and profits.[68] Importantly however, a majority respondents still selected ‘clan’ culture as the most prominent type, with ‘market’ in second place.[69] Thus, rather than a complete restructuring of enterprise organization, there has been a particular convergence between pre and post reform management styles, which is likely to have been caused by the influence of Western training of Chinese management.[70] Another aspect of this are the vast numbers of Chinese students, who study abroad either in high school and later on at a university. By 2015, over four million Chinese students have studied abroad since 1978.[71] What makes this number even more impactful is the fact that the share of students returning from abroad with graduate degrees is continuously rising, amounting to 79% in the year 2016.[72]

Overall, the examples above illustrate the existing combinations in the Chinese socio-economic landscape. While the marketization of labour power was borrowed from Western capitalism[73], both the hukou and the danwei are notable Chinese characteristics that have undergone reform but remain influential and thereby shape today’s Chinese labour market into an amalgam of internal and external influences. Similarly, the new forms of SOE management also signify a form of combined development, which surfaces through the interaction of a previously dominant ‘clan’ enterprise organisation and Western management education. These examples show that far from posing a paradox, the peculiarities of Chinese development emerged as a result of the process of uneven and combined development.

Conclusion

Before drawing the final conclusion, let us briefly consider a crucial point. This essay has set out to understand the specific impact of U&CD on China. Despite not being the focus of this essay, it is important to keep in mind that by default, the same interaction between China and the global economy has also caused combined forms of development in the latter. In conclusion, this essay has presented the argument that the theory of U&CD provides an effective way to conceptualize the particular outcomes of Chinese economic development. Further, through applying U&CD we can resolve what first appears as a paradox – capitalist development under a self-titled communist regime. This is possible through examining the specific forms of combined development that are a manifestation of the interaction between China and the capitalist world economy, driven by the ‘whip of external necessity’ that was exerted on China in 1978. This was exemplified in this essay through the examples of the impact of the hukou and danwei on capitalist labour relations, as well as the impact of Western education and market integration on Chinese SOE management structures. In sum, we can derive from this analysis that an understanding of ‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics’ requires a thorough examination into the internal and external forces that initially led to their development.

Bibliography

Boyle, C.; Rosenberg, J. (2018). ‘Explaining 2016: Brexit and Trump in the History of Uneven and Combined Development’. (Unpublished Manuscript, University of Sussex).

Chan, K.; Zhang, L. (1999). ‘The Hukou System and Rural-Urban Migration in China: Processes and Changes’. In: The China Quarterly, Vol. 160, pp. 818-855. Online, available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656045 [Accessed: 26/04/2018].

Clover, C.; Sherry, J. (2016). ‘Didi Chuxing to be hit by rules on migrant drivers’. In: Financial Times. Online, available at: https://www.ft.com/content/ac21babe-91f8-11e6-a72e-b428cb934b78 [Accessed 05/05/2018].

Cohen, M. A. (2012). ‘Argentina’s Economic Growth and Recovery: The Economy in a Time of Default’. New York: Routledge.

Davidson, N. (2017). ‘Uneven and Combined Development: Modernity, Modernism, Revolution’. Online, available at: https://www.rs21.org.uk/2017/03/03/pdf-revolutionary-reflections-uneven-and-combined-development-modernity-modernism-revolution-5-china-where-all-roads-meet/ (page numbers taken from PDF) [Accessed: 20/04/2018].

Deutscher, I. (1984). ‘Marxism, Wars and Revolutions’. London: Verso.

Dunford, M.; Weidong, L. (2017). ‘A Century of Uneven and Combined Development: The Erosion of United States Hegemony and The Rise of China’. In: Вестник Мгимо-Университета, Vol. 5(56), pp. 7-32. Online, available at DOI:10.24833/2071-8160-2017-5-56-7-32 [Accessed: 23/04/2018].

Fan, C. (1995). ‘Of Belts and Ladders: State Policy and Uneven Regional Development in Post-Mao China’. In: Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 85(3), pp. 421-449. Online, available at DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1995.tb01807.x [Accessed 01/05/2018].

Huang, Y. (2008). ‘Capitalism with Chinese characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State’. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hung, H. (2013). ‘Labor Politics under Three Stages of Chinese Capitalism’. In: The South Atlantic Quarterly, Vol. 112(1), pp. 203-212. Online, available at DOI:10.1215/00382876-1891341 [Accessed: 26/04/2018].

Hung, H. (2016) ‘The China Boom: Why China will not rule the world’. New York: Columbia University Press.

ICEF – Data taken from: http://monitor.icef.com/2018/02/increasing-numbers-chinese-graduates-returning-home-overseas/

IMF – Data taken from: World Economic Outlook Database 2018

Kerr, D. (2007). ‘Has China abandoned self-reliance?’ In: Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 14(1), pp. 77-104. Online, available at DOI: 10.1080/09692290601081178 [Accessed 05/05/2018].

Knight, J.; Song, L. (2005). ‘Labour Policy and Progress: Overview’. Chapter 2 in: Towards a Labour Market in China. Oxford Scholarship Online, available at DOI:10.1093/0199245274.003.0002 [Accessed: 28/04/2018].

Lin, J. (2011). ‘The comparative advantage-defying, catching-up strategy and the traditional economic system’. Chapter 4 in: Demystifying the Chinese Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Online, available at DOI:10.1017/CBO9781139026666.005 [Accessed 01/05/2018].

Lorenz, A.; Wagner, W. (2007). ‘Red China, Inc. – Does Communism Work After All?’. In: Der Spiegel. Online, available at: http://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/red-china-inc-does-communism-work-after-all-a-465007.html [Accessed 02/05/2018].

Meisner, M. (1996). ‘The Deng Xiaoping Era – An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994’. Toronto: HarperCollins Canada Ltd.

Oi, J. C. (1999). ’Two Decades of Rural Reform in China: An Overview and Assessment’. In: The China Quarterly, No. 159, Special Issue: The People’s Republic of China after 50 Years, pp. 616-628. Online, available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/655756 [Accessed: 26/04/2018].

Ralston, D., et al. (2006). ‘Today’s State-Owned Enterprises of China: Are They Dying Dinosaurs or Dynamic Dynamos?’. In: Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 27, pp. 825–843. Online, available at DOI:10.1002/smj.545 [Accessed 05/05/2018].

Rosenberg, J. (1994). ‘The Empire of Civil Society’. London: Verso.

Rosenberg, J. (2013). `Kenneth Waltz and Leon Trotsky: Anarchy in the mirror of uneven and combined development’, In: International Politics Vol. 50(2), pp. 183-230. Online, available at DOI:10.1057/ip.2013.6 [Accessed 25/04/2018].

Rosenberg, J., (2016). ‘Uneven and Combined Development: ‘The International’ in Theory and History’. Chapter 2 in: Anievas, A. & Matin, K. (eds.), Historical Sociology and World History: Uneven and Combined Development over the Longue Durée. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Trotsky, L. [1932(2007)]. ‘History of the Russian Revolution’. Chicago: Haymarket Books. Online, Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central [Accessed 01/05/2018].

Walker, R.; Buck, D. (2007). ‘The Chinese Road: Cities in the Transition to Capitalism’. In: New Left Review, Vol. 46, pp. 39-66. Online, available at: https://newleftreview-org.ezproxy.sussex.ac.uk/II/46/richard-walker-daniel-buck-the-chinese-road [Accessed: 26/04/2018].

Wang, F. (2004). ‘Reformed Migration Control and New Targeted People: China’s Hukou System in the 2000s’. In: The China Quarterly, Vol. 177, pp. 115-132. Online, available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20192307 [Accessed: 26/04/2018].

Warner, M. (1987). ‘China’s Managerial Training Revolution’. Chapter 5 in: Management Reforms in China, Warner, M. (ed). London: Frances Pinter.

Xie, Y. et al. (2009). ‘Danwei and Social Inequality in Contemporary Urban China’. In: Res Social Work, Vol. 1(19), pp. 283-306. Online, available at doi:10.1108/S0277-2833(2009)0000019013 [Accessed 05/05/2018].

Zhang, D.; Unschuld, P. (2008). ‘China’s barefoot doctor: past, present, and future’. In: The Lancet, Vol. 372, pp. 1865-1867. Online, available at DOI:10.1016/S0140- 6736(08)61353-7 [Accessed: 28/04/2018].

Notes

[1] IMF – World Economic Outlook Database 2018

[2] Lorenz, A.; Wagner, W. (2007). ‘Red China, Inc. – Does Communism Work After All?’. In: Der Spiegel.

[3] Meisner, M. (1996). ‘The Deng Xiaoping Era – An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994’. Toronto: HarperCollins Canada Ltd, p. xii.

[4] Cohen, M. A. (2012). ‘Argentina’s Economic Growth and Recovery: The Economy in a Time of Default’. New York: Routledge, p. xvii.

[5] Huang, Y. (2008). ‘Capitalism with Chinese characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State’. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[6] Oi, J. C. (1999). ’Two Decades of Rural Reform in China: An Overview and Assessment’. In: The China Quarterly, No. 159, Special Issue: The People’s Republic of China after 50 Years, p. 627.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Huang, Y. (2008), p. xviii.

[9] Ibid., p. 8.

[10] Rosenberg, J., (2016). ‘Uneven and Combined Development: ‘The International’ in Theory and History’. Chapter 2 in: Anievas, A. & Matin, K. (eds.), Historical Sociology and World History: Uneven and Combined Development over the Longue Durée. London: Rowman & Littlefield International, pp. 18-19.

[11] Meisner, M. (1996), p. 18.

[12] Deutscher, I. (1984). ‘Marxism, Wars and Revolutions’. London: Verso, p. 195.

[13] Ibid., pp. 205-06.

[14] Hung, H. (2013). ‘Labor Politics under Three Stages of Chinese Capitalism’. In: The South Atlantic Quarterly, Vol. 112(1), p. 205.

[15] Hung, H. (2016) ‘The China Boom: Why China will not rule the world’. New York: Columbia University Press, p. 47.

[16] Zhang, D.; Unschuld, P. (2008). ‘China’s barefoot doctor: past, present, and future’. In: The Lancet, Vol. 372, p. 1865.

[17] Ibid., pp. 1865-66.

[18] Meisner, M. (1996), p. 194.

[19] Hung, H. (2016), p. 48.

[20] Boyle, C.; Rosenberg, J. (2018). ‘Explaining 2016: Brexit and Trump in the History of Uneven and Combined Development’. (Unpublished Manuscript, University of Sussex), p.11.

[21] Rosenberg, J., (2016), pp. 21-22.

[22] Trotsky, L. [1932(2007)]. ‘History of the Russian Revolution’. Chicago: Haymarket Books, p. 5.

[23] Rosenberg, J., (2016), p. 17.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Trotsky, L. [1932(2007)], p. 4.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Rosenberg, J. (2013). `Kenneth Waltz and Leon Trotsky: Anarchy in the mirror of uneven and combined development’, In: International Politics Vol. 50(2), p.196.

[28] Trotsky, L. [1932(2007)], p. 5.

[29] Fan, C. (1995). ‘Of Belts and Ladders: State Policy and Uneven Regional Development in Post-Mao China’. In: Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 85(3), p. 422.

[30] Meisner, M. (1996), p. 199.

[31] Lin, J. (2011). ‘The comparative advantage-defying, catching-up strategy and the traditional economic system’. Chapter 4 in: Demystifying the Chinese Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 102.

[32] Meisner, M. (1996), p. 201.

[33] Boyle, C.; Rosenberg, J. (2018), p. 12.

[34] Hung, H. (2013), p. 205.

[35] Kerr, D. (2007). ‘Has China abandoned self-reliance?’ In: Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 14(1), p. 83.

[36] Boyle, C.; Rosenberg, J. (2018), p. 8.

[37] Knight, J.; Song, L. (2005). ‘Labour Policy and Progress: Overview’. Chapter 2 in: Towards a Labour Market in China. Oxford Scholarship, p. 20.

[38] Davidson, N. (2017). ‘Uneven and Combined Development: Modernity, Modernism, Revolution’, p. 82.

[39] Dunford, M.; Weidong, L. (2017). ‘A Century of Uneven and Combined Development: The Erosion of United States Hegemony and The Rise of China’. In: Вестник Мгимо-Университета, Vol. 5(56), pp. 7-32.

[40] For Hukou see: Chan, K.; Zhang, L. (1999). ‘The Hukou System and Rural-Urban Migration in China: Processes and Changes’. In: The China Quarterly, Vol. 160, p. 819. For Danwei see: Xie, Y. et al. (2009). ‘Danwei and Social Inequality in Contemporary Urban China’. In: Res Social Work, Vol. 1(19), p. 283.

[41] Knight, J.; Song, L. (2005), pp. 26-27.

[42] Ibid., p. 41.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Xie, Y. et al. (2009), p. 283.

[45] Ibid., p. 294.

[46] Ibid., p. 286.

[47] Ibid., p. 294.

[48] Chan, K.; Zhang, L. (1999), p. 830.

[49] Wang, F. (2004). ‘Reformed Migration Control and New Targeted People: China’s Hukou System in the 2000s’. In: The China Quarterly, Vol. 177, p. 116.

[50] Knight, J.; Song, L. (2005), p. 25.

[51] Chan, K.; Zhang, L. (1999), p. 839.

[52] Wang, F. (2004), p. 129.

[53] Knight, J.; Song, L. (2005), p. 22.

[54] Walker, R.; Buck, D. (2007). ‘The Chinese Road: Cities in the Transition to Capitalism’. In: New Left Review, Vol. 46, p. 44.

[55] Davidson, N. (2017), p. 85.

[56] Chan, K.; Zhang, L. (1999), p. 831.

[57] Hung, H. (2013), p. 209.

[58] Marx, K., quoted in Rosenberg, J. (1994). ‘The Empire of Civil Society’. London: Verso, 144.

[59] Hung, H. (2013), p. 204.

[60] Meisner, M. (1996), p. 523.

[61] Clover, C.; Sherry, J. (2016). ‘Didi Chuxing to be hit by rules on migrant drivers’. In: Financial Times.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Walker, R.; Buck, D. (2007), p. 55.

[64] Oi, J. C. (1999), p. 625.

[65] Warner, M. (1987). ‘China’s Managerial Training Revolution’. Chapter 5 in: Management Reforms in China, Warner, M. (ed). London: Frances Pinter, p. 73.

[66] Ralston, D., et al. (2006). ‘Today’s State-Owned Enterprises of China: Are They Dying Dinosaurs or Dynamic Dynamos?’. In: Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 27, p. 833.

[67] Ibid., p. 831-32.

[68] Ibid., p. 839.

[69] Ibid., p. 838.

[70] Ibid., p. 838-39.

[71] Boyle, C.; Rosenberg, J. (2018), p. 14.

[72] ICEF: Increasing Numbers of Chinese Graduates Returning Home

[73] Meisner, M. (1996), p. 493.

Varieties of Capitalism and Rethinking the East Asian Model

In their work on varieties of capitalism (VoC), Soskice and Hall (2001) identified several types of capitalism, such as liberal market economies (LMEs), coordinated market economies (CMEs), and mixed market economies (MMEs). They argue that each type of capitalism is stable and efficient in terms of its economic performance, owing to complementarity among its institutional components. However, Lee and Shin (2018) show that each type corresponds to different economic outcomes in terms of economic growth, unemployment, and equity. They also observe that the change of a country from one type to another has led to the existence of convergence and divergence among countries.

A similar contrast was also made in Acemoglu et al. (2012), when they considered the US model of capitalism and the Western European model as “cutthroat” capitalism versus “cuddly” capitalism, respectively. Cutthroat capitalism is good for innovation but generates inequality, whereas cuddly capitalism is better at redistributing income and protecting employment and health, but worse at producing frontier innovation. Aghion et al (2020) try to compare the US and Western European models again in terms of how they are dealing with and responding to the Covid-19 crisis.

This paper focuses on East Asian economies led by Japan, followed by the Asian Tigers, namely, Korea and Taiwan, to discuss the evolution of their performance and changes in type over time, from the VoC perspective. First, I discuss the interesting puzzle of the emerging convergence of Japan and Korea toward the LMEs or Anglo–Saxon economy, despite the apparent differences in underlying institutions: labour market, corporate governance, and welfare systems. Then, I identify the financialisation of an economy as a force that drives this convergence, signalled by decreasing economic growth rates and rising inequality in East Asia. Finally, I re-evaluate Asian economies in the context of the coronavirus disease in 2019, the ‘Covid-19 pandemic’, which has suddenly halted globalisation and further questioned the superiority of shareholder capitalism, mostly adopted in LMEs and associated with financialisation and globalisation.

I argue that a new balance is needed between shareholder and the stakeholder capitalism in East Asia. I also discuss the implications of the retreat of globalisation for East Asia and other emerging economies in general, in terms of the “globalization paradox” proposed by Rodrik (2011). I argue that the retreat of globalisation is a good opportunity to resolve the paradox or the ‘trilemma’ by restoring autonomy in domestic economic policymaking over interest rates and exchange rates, while imposing some adjustments on formerly excessive capital mobility. These changes in policy stance are required to build a crisis-resilient macro-financial system, given the brewing of the post-pandemic bubble and the increasing mismatch between real and financial sectors around the world.

Varieties of Capitalism, Financialisation, and the End of East Asian Capitalism

Soskice and Hall (2001) have provided an important way to understand and compare economic systems around the world. They focus on how firms enter into a relationship with other actors, such as workers, suppliers, business associations, governments, and other stakeholders. According to Soskice and Hall (2001), an economy is classified as an LME when firms use market institutions, such as competition and formal contracts, to coordinate a relationship. Alternately, an economy is classified as a CME when firms use a non-market relationship, such as strategic interaction among actors, as a form of coordination. Accordingly, they classify the US, the UK, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Ireland as LMEs; Germany, Japan, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Austria as CMEs; and France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Turkey as countries with an ambiguous position as MMEs. These classifications are similar to the existing conventional classification, that is, most LMEs are UK or US-offspring countries, whereas CMEs comprise mostly Continental and Northern European countries.

I aim to understand East Asian economies, especially Japan and the Asian Tigers, namely, Korea, Taiwan, given their spectacular achievements in terms of growth and equity. Their economies tended to feature high growth and low inequality during their peak growth, which has earned them the label of East Asian miracles by the World Bank (1993). Kalinowski (2015) shows that East Asian capitalism remains a distinct state-led model that differed from the liberal, neo-corporatist, or welfare state capitalism in the West in terms of its reaction to the global economic crisis in 2008 by using big fiscal stimulus packages. This difference may be associated with a path-dependent transformation of the East Asian developmental state (Kim and Thurbon 2015; Thurbon 2016).

However, these economies have recently been going through radical changes as they record slow growth and rising inequality. The new situations lead to questions on whether we are facing the end of East Asian capitalism (characterised by high growth and low inequality) and convergence toward the LME (characterised by low growth and high inequality). Lee and Shin (2018) confirm this hypothesis by using a quantitative (cluster) analysis. This is different from the VoC literature, which tends to use the variables representing the underlying institutional characteristics of economies. Lee and Shin (2018) use outcome variables to compare economic performance, including the growth rate of GDP per capita, employment rate, and top 10% income share.

As shown in Table 1, a statistical analysis by Lee and Shin (2018) indicate that the LME group is associated with slow growth, high inequality, and a medium level of employment, whereas the CME group has modest growth, low inequality, and sound employment rates. Between these two groups is the MME group, with the lowest rates of employment, which probably reflect labour market rigidity. The East Asian group exhibits the highest growth and lowest inequality but only before the 2000s. In the 2000s and after, Japan and Korea joined the LME group and Taiwan joined the CME group, leaving the former East Asian group empty. Their choices may imply the end of East Asian capitalism. These results are not that surprising because the top 10% share of the national income is currently the highest in the US, at over 45%, followed closely by Korea, reaching 45% in 2010, and Japan with 40% (Lee and Shin 2018). Korea and Japan have experienced disruption, or crisis, such as the bubble and burst of the 1990s in Japan and the 1997 financial crisis in Korea, that led to a liberal and open economy (Shin and Lee 2018; Lee et al. 2020). During the crisis, Korea implemented IMF policy prescriptions in exchange for a bailout loan (Lee et al. 2002). Japan has also experienced a similar change since the burst of its economic bubble in the late 1990s. In particular, the Koizumi administration implemented liberalization policies, such as privatization and deregulation, from 2001.

Table 1: Four types of capitalism and their economic outcomes

Many institutions in Japan and Korea have evolved similarly to those in the US. First, the financial market is liberalised to allow more foreign shares of stocks and to strengthen shareholder capitalism. Second, the labour market is liberalised to promote labour flexibility and weaken the long-term employment system. Consequently, the share of part-time or irregular workers to the total employment rate has rapidly increased in Japan and Korea (Shin and Lee 2018; Lee et al. 2020). In the meantime, the divergence between Korea and Taiwan seems to be driven by the top 10% income share; the top 10% income share has increased gradually in Taiwan but at much slower rates than in South Korea since the late 1990s. This difference in the evolution of inequality between these two economies may be caused by various shocks from the Asian financial crisis, which strongly affected the South Korean economy, but minimally affected the Taiwanese economy, which avoided the crisis (Lee et al. 2020).

The above discussion presents the foundation to argue for the convergence of East Asian capitalism toward Anglo–Saxon capitalism. However, the question remains as to how this convergence can happen despite the continuing differences in underlying institutions, such as labour, financial systems, firm ownership, and governance. For instance, despite some trends toward flexibility, the labour markets in Korea and Japan are still less flexible than those in the US or the UK. Moreover, the nature of firm ownership and government in Asia is also quite different from that in the US or the UK, where ownership is quite dispersed over a large number of individual investors. Consequently, the forces that push these economies toward the LME group in terms of slow growth and high inequality remain unknown. The strong candidate variable must be the tendency for financialisation (Lee et al. 2020).

An increasing volume of literature has focused on the negative aspect of financialisation coupled with shareholder capitalism, which forces firms to pay high dividends to shareholders rather than use profits for reinvestment, which leads to slow growth (Dore et al. 1999; Lazonick 2010, 2014). The growing dominance of financial sectors is related to rising income inequality in developed countries (Alvarez 2015; Godechot 2012; Hacker and Pierson 2010; Kus 2012; Lin and Tomaskovic-Devey 2013; Stockhammer 2013; Tomaskovic-Devey et al. 2015). In the Korean context, Kim and Cho (2008) confirm that firms with high shares of equity owned by foreign shareholders tend to be associated with low investment because they are subject to demands by shareholders for more dividends. In many economies, including the US and Korea, capital markets no longer function as sources of additional funding for listed companies, but rather as a channel for value extraction in the form of stock repurchases and dividends (Lazonick and Shin 2019).[1] Lee et al. (2020) confirm this tendency for value extraction, which is that more money has flowed out of, rather than into, Korean listed firms since 2003, although such firms previously enjoyed a net positive inflow of money.

The macro-level consequences of this situation are the decreasing of fixed capital investment as a share of GDP and the increasing outflow of capital (in the form of repatriated profits and interest payments) in balance-of-payment figures.[2] In other words, the rise of shareholder capitalism, which prioritizes distributing profits as dividends to shareholders rather than funding reinvestment, seems to be slowing down investment, which in turn slows down economic growth rates. This symptom, associated with financialisation, is also a source of increasing income inequality, in addition to effects of skill-biased technological changes, including automation. Shin and Lee (2019) show that increased shares of stockholders in profits or financial resources of non-financial sectors have led to rising inequality, measured by the top 10% income share in OECD countries, whereas the influence of skill-biased technological change (which is perceived to lead to more inequality among labour-based incomes) is not a robust enough variable to explain inequality.

Financial globalisation is argued to cause rising inequality. Stockhammer (2013) finds that financial globalisation, measured by the log of external financial assets and liabilities divided by GDP, is significantly and negatively correlated with labour income share by using country-level data. Distinguishing financialisation and ‘financial development’, meaning ‘better functioning of financial markets’, Lee and Shin (2019) find no support for the argument that financial development, such as the high ratio of stock market valuation to GDP, reduces inequality by relaxing the credit constraints of the poor and see no evidence that financial development aggravates inequality. A simple focus on financial development or high education is not sufficient to reduce inequality (Lee and Shin 2019). Thus, government policies or reform measures, including differentiated taxation on dividends and reinvestments, are necessary to curve financialisation by inducing non-financial firms to focus on productive reinvestment from profits and by discouraging high dividends for shareholders.

Covid-19 and the Rebalance between Shareholder and Stakeholder Capitalism

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a major shock to the world economy and its constituent economies, including the varieties of capitalist economies. A big blunt has been observed in the US, which has not recovered as quickly as Western European economies and Asian economies such as China, Korea, and Japan (Popov 2020). Western European economies have also revealed their weaknesses in their initial responses and thus suffered greatly. One of the common weaknesses of the Western world is its reliance on East Asia for the production of masks and other medical devices, including the test kits. Overall GVC (global production chains) have revealed weakness associated with too widespread a fragmentation over diverse countries. Thus, Covid-19 also signals the retreats of the Anglo–Saxon style shareholder capitalism that has driven globalisation or neoliberalism since the 1980s. Since the 1980s, the efficiency or profit maximisation forced by shareholders seeking short-term profit has resulted in a high degree of globalisation of production chains.

Lazonick (2010, 2014) points out that the US economy maintained manufacturing until the 1980s but the rise of shareholder capitalism and financialisation since then has forced US firms to relocate their factories abroad to meet the demands of shareholders and increase profitability. This change has turned the US economy into a service-oriented economy with the hollowing out of the manufacturing industry. Lee and Shin (2019; table 1) confirm that the LMEs as a group with more than two member economies was only observed in the mid-1980s, and the US joined Canada and the UK to form the LME group only during the late 1980s or the early 1990s. This emergence of the LMEs since the mid-1980s is consistent with neoliberalism being dominant only since the 1980s.

Shareholder capitalism is again being criticised after the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak. For example, Boeing was heavily criticised when the company asked for financial help from the public sector because it paid – before the pandemic outbreak – a huge amount of money to its shareholders (with its top five all PEFs) in the form of dividends and stock buybacks, rather than reserved profits for in-house reserves or reinvestment funds. Even before the pandemic crisis, the top firms and their business leaders declared their desire to reset capitalism toward more consideration for various stakeholders besides just shareholders. These changes have been signaled by a series of occasions, including the August 2019 ‘Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation’ by the top 181 business leaders in Washington DC in the US, which was immediately followed by the initiatives of the Financial Times under the heading of ‘Capitalism: Time for a reset’. These movements culminated in the January 2020 Davos Forum, which endorsed stakeholder capitalism as the vision for the future of capitalism.

The pandemic is the final blow to globalization, or over-fragmented GVC, after the two preceding blows of the 2008-09 global financial crisis (GFC) and the US-China trade war. The GFC was the first blow to financial globalization, followed by the setback against trade globalization of the US-China trade war. Finally, the pandemic outbreak signaled a major setback to production globalization. Just as the pandemic is considered a warning against human destruction of the environment, it is also a call to restore the vitality of the capitalist market economy by rebalancing against over-globalization and over-loaded shareholder capitalism. Shareholder capitalism and globalization have been pointed out in economics literature as the main sources of low growth and high inequality, as discussed in the preceding section.

While the Covid-19 crisis has indicated more advantages toward manufacturing-oriented economies than service-oriented economies, East Asian economies, such as Korea, are also suffering from slow growth and rising inequality that have been exacerbated since the pandemic. One aspect of the necessary reforms is the correction of the tendency of financialisation associated with shareholder capitalism, which includes a practice that provides equal rights to short- or long-term shareholders in terms of rights for voting and dividends. Measures that promote long-term holdings of stocks and thus enhance firm value are also needed to provide privileges to long-term shareholders, which is consistent with the idea of stakeholder capitalism.

The idea of stakeholder capitalism is that firms are to be run in the interests of a broad spectrum of stakeholders that include not only shareholders but also clients, managers, workers, and nearby communities, who are often holders of long-term, firm-specific interests and even stocks. Thus, providing the same voting and dividend rights to those who own stocks for only several years and weeks does not promote enhancement of the long-term value of firms, and it may lead to short-term profits or performance-seeking value.

East Asia may learn from the EU, which has initiated several reforms to curb the negative influence of shareholder capitalism. The EU Parliament passed a law in 2015 that changed its firms’ corporate governance (Stabilini 2015). The new law allows firms to provide more voting rights or more dividends to tenured or long-term shareholders who hold their stocks for more than two years. Following this law, the 2014 Florange Act has been implemented in France. Owing to this Act, many of the firms (or more than 54%) in the French stock market, including Electricite de France, Air Liquide, Credit Agricole, L’Oreal, Lafarge, and Group SEB, have opted to issue stocks that provide special favour to tenured stockholders. These new innovative practices are not possible under the current corporate law in Korea, which follows the idea of shareholder capitalism by sticking strictly to the rule of one share and one vote, regardless of holding period.

East Asian states, such as Korea, may learn from other countries and seriously consider changing their corporate law. Even the US allows its firms to issue dual-class stocks in the initial public offering in NASDAQ, which gives special favour in terms of voting power to the founders of the firms. Using this clause, the founders of many high-tech firms in the US may manage their firms from long-term perspectives and tend to be aggressive in trying innovative new projects. These dual-class stocks are all issued to US firms, including Facebook, Google, and Amazon (Zeiler 2014).

In sum, East Asian economies may take the Covid-19 crisis as an opportunity to turn their economies around by adopting measures that can curb the ongoing tendency of financialisation and restore the original strength of Asian capitalism, such as high growth and good equity. Instead of maintaining the old version of East Asian capitalism, they can also be reborn through hybrid capitalism, rebalancing elements from shareholder and the stakeholder capitalism with East Asian capitalism at its original core.

The Globalisation Paradox and a Crisis-Resilient Macro-Finance System: The Case of Korea

Globalisation has become stalled by a series of events, including the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak. The consequences of this change for emerging economies can be interpreted by the “globalization paradox” raised by Rodrik (2011). In his book, Rodrik (2011) proposes a trilemma that globalization, national sovereignty, and democracy cannot go together, and thus one can have only two out of the three. He argues that globalization tends to suppress either national sovereignty or democracy because it often tends to consider the interests of global businesses the top priority against the interests of the national government or workers. Under globalization, the national government is left with less room or tools for domestic economic policies, including interest rates and exchange rates. With globalization suddenly stalled after the pandemic and affected by the rising protectionism of the Trump government in the US, alternative economic systemic arrangements can be explored to provide autonomy in domestic economic policies for emerging countries. In particular, given the possibility of financial crises that may result from the mismatch between a quick financial recovery versus weak non-financial businesses, owing to the massive release of diverse kinds of emergency loans, subsidies, and the printing of money in some countries as an aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak, emerging countries are advised to install a crisis-resilient macro-financial system in preparation for the coming burst of the financial bubble built over the pandemic period.

The globalization trilemma can be compared with the conventional trilemma (or the ‘impossible trinity’) in macroeconomics, such that free capital mobility, autonomous monetary policy (interest rates), and free-floating exchange rates cannot go together and at least one out of the three has to be sacrificed. Thus, advanced economies tend to choose the combination of free capital mobility and autonomous monetary policy. By contrast, some of the emerging economies, such as Korea before its OECD entry in 1993, tend to favour autonomous monetary and exchange rates as trades are extremely important for catch-up stages of economic development. This combination of a twin autonomy of interest rates and exchange rates is implemented well in many emerging economies at their catching-up growth stage, including China. By contrast, premature financial liberalization for free capital mobility has often resulted in a financial crisis, as shown by the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. Consequently, even the IMF has become cautious about suggesting full-scale financial liberalization and acknowledged the necessity of active management of the capital account (capital control) under certain conditions (Ostry et al. 2010).

The IMF, the World Bank, or the Washington Consensus (Williamson 1990) used to propose financial liberalization for emerging economies, implying that it would bring in more financial resources for an economy lacking domestic funds. However, more often than not, financial liberalisation is followed by financial crisis rather than steady economic growth, as observed in the 1997 Asian crisis involving Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia. While these economies had to ask for the emergency loans from the IMF, only Malaysia avoided this situation by imposing capital controls. Korea embraced the first wave of radical liberalization of capital accounts as a requirement to join the OECD – which is considered a club of rich countries – in the mid-1990s. The outbound financial liberalization had enabled chaebols (Korean big businesses) to borrow funds nominated in USD at much lower rates in the international market than in the domestic banks. The 1997 Asian financial crisis can be attributed to this “premature” or careless integration “into international financial markets, excessive short-term borrowing abroad with a maturity mismatch, and weak domestic financial sectors” (Nayyar 2019, p. 83).

The post-crisis reform package implemented in Korea is one of the most comprehensive and decisive set of reforms undertaken by any country following a major crisis (Lee 2016, p. 112). Numerous Korean institutions were forced to change or evolve, similarly to those in the US (Lee et al. 2002). For instance, the financial market was liberalized and most restrictions on foreigners’ domestic investments were lifted. Consequently, foreigners’ share of stocks in Korean firms increased rapidly from less than 3% in the mid-1990s to more than 40% in the 2000s, which strengthened shareholder capitalism. Jang-Sup Shin and Ha-Joon Chang (2003) argue that the IMF programme demanded Korea pay an extremely expensive price to follow a neoliberal or Anglo–Saxon model, which is not suitable for a country with newly achieved compressed development.

However, this comprehensive reform and another round of financial liberalization have not been effective in protecting Korea from the risk of another financial crisis in the aftermath of the 2008-09 GFC. During the onset of the GFC, hot money suddenly flew out of Korea to go back to the Wall Street because of a liquidity crisis at the heart of capitalism, and thus the Korean Won again suffered a huge and sudden depreciation (Lee et al. 2020). This situation stopped only after Korea agreed a bilateral currency swap with the US which enabled the supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market in Korea and was ineffective for 15 months. Korea learned a hard lesson from the negative spillover of the crisis in Wall Street in 2008-09. The Korean experience may provide some hint in seeking a blueprint for a crisis-resilient macro-financial system, which would also make sense in this post-pandemic era.

Following Williamson (1999) and Ferrari-Filho and Paula (2008), Lee (2016) proposes a kind of macro-policy framework that can be described as “an intermediate system” with managed capital mobility and an explicit option of Tobin taxes, a version of the managed or flexible BBC (basket, band, crawl) exchange rate system, and with relative independence in monetary policymaking with a new balance between interest-rate and exchange-rate targeting. With regard to specific macro-level measures, fees on short-term financial flow (or Tobin tax) and reserve requirements are suggested, discouraging the buying and selling of foreign exchange for extremely short-term purposes (Lee 2016; Lee et al 2020).[3] At the micro-level, the key task against external shocks is to manage foreign assets and liabilities in corporate and bank dimensions. In particular, the level of and trend in short-term foreign liability need to be managed and monitored, covering not only domestic banks but also domestic branches of foreign banks, and the optimal hedge ratio needs to be used as a sophisticated investment strategy. For example, a minimum requirement in the ratio of foreign liquid assets over total foreign assets is suggested. A core funding ratio, such as foreign loan to foreign deposit, is also recommended. It helps not only reduce currency mismatch but also increases the core funding base, which is relatively stable even in times of financial turmoil.

Some of these measures were adopted by the Korean government in 2011 in the name of ‘three macro-prudential’ measures, including regulations on banks’ positions in forward exchange markets (150% of equity capital), taxes on non-deposit foreign exchange debt, and the LCR (liquidity coverage ratio) which is the regulation of minimum high-liquidity foreign exchange-based assets (e.g., US treasury bonds) to be held against net cash outflow expected for a month (e.g., withdrawal of deposits), in addition to a tax on foreigners’ interests income from holding Korean bonds (Lee 2016, p. 143). Since then, the Korean economy has maintained stability in the macroeconomic sense. However, managing the possibility of sudden inbound or outbound flows of short-term capital remains a challenge. In this post-pandemic recession, all the emerging economies tend to lower their interest rates but this measure may increase the possibility of capital flight whenever an exogenous shock is observed. Following Korea’s policy initiatives associated with the ‘three macro-prudential’ measures, each country is advised to conceive and install its own schemes for macro stability.

These three measures worked again during the economic shock from Covid-19. In March 2020, global financial markets were suffering from the shock of the outbreak of the pandemic. As a precautionary measure, on 19 March, the US federal reserve board extended Dollar swap lines to nine economies – Korea, Brazil, Mexico, Singapore, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, New Zealand and Australia – in addition to the existing swap agreement with the five core advanced economies. This sudden intervention helped to stabilise the foreign exchange market facing the sharp explosion of demand for dollars. In the Korean market, the exchange rates dropped or decreased from about 1,300 Won per dollar to 1,200 Won by the end of June.

Besides this currency swap, the three macro-prudential measures had an additional stabilising role by reducing the possibility of capital flight. First, the Bank of Korea decided that the commercial banks’ position in forward exchange markets was now enlarged from the prevailing 200% to 250% of equity capital for Korean branches of foreign banks, and from 40% to 50% for domestic banks.[4] Second, no taxes will be charged on the increased amount of non-deposit foreign exchange debt incurred to commercial banks during the three months from April to June 2020. Third, the Ministry of Finance of the Korean government announced that the LCR (liquidity coverage ratio) was now reduced from the prevailing ratio of 80% to 70% until May 2020.[5] These cases suggest that these measures can be useful in adjusting the inflow and outflow of hot money during the times of macro-financial uncertainty, particularly for emerging economies without reserve currency.

Summary and Concluding Remarks

As reflected in the expression “East Asian miracle” (World Bank 1993), East Asian economies saw remarkable performance of high growth and low inequality, thereby forming a separate East Asian capitalism group within the VoC typologies. There are strong signs that these economies have recently been converging to the LME group, featuring low growth and high inequality, features shared by East Asian economies since the 2000s. Financialisation is arguably one cause for these outcomes of low growth and high inequality. I re-evaluate East Asian capitalism in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has suddenly halted globalization and further questioned the superiority of shareholder capitalism associated with financialisation and globalization. I propose rebalancing between shareholder and stakeholder capitalism. By doing so, East Asian economies can be reborn as a hybrid capitalism, with East Asian capitalism at its original core, to restore their growth momentum in an inclusive way. I also argue that the post-pandemic retreat of globalisation is a good opportunity to restore autonomy in domestic economic policymaking over interest rates and exchange rates, while imposing some adjustments over formerly excessive capital mobility.

Keun Lee

References

Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J. A., and Verdier, T. (2012). Can’t We All Be More Like Scandinavians? Asymmetric Growth and Institutions in an Interdependent World. MIT Department of Economics Working Paper No. 12-22.

Aghion, Philippe, Maghin, Helene, and Sapir, André (2020). Covid and the nature of capitalism. Vox EU. Available at https://voxeu.org/article/covid-and-nature-capitalism.

Alvarez, I. (2015). Financialization, non-financial corporations and income inequality: the. case of France. Socio-Economic Review 13(3), 449-475.

Dore, R., Lazonick, W., Sullivan, M. (1999). Varieties of capitalism in the twentieth. century. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 15(4), 102-120.

Ferrari-Filho, F. and Paula, L. (2008) Exchange rate regime proposal for emerging countries: A Keynesian perspective, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, Vol. 31.

Godechot, O. (2012). Is finance responsible for the rise in wage inequality in France? Socio-Economic Review 10(3), 447-470.

Hacker, J. S., Pierson, P. (2010). Winner-take-all politics: Public policy, political organization, and the precipitous rise of top incomes in the United States. Politics & Society 38(2), 152-204.

Kim, A., Cho, M.-H. (2008). Types of Foreign Investors, Dividend and Investment Policy: An. Empirical Study of. Korean Firms. Journal of Strategic Management 11(1), 25-42

Kim, S.-Y., Thurbon, E. (2015). Developmental environmentalism: Explaining South Korea’s ambitious pursuit of green growth. Politics & Society 43(2), 213-240

Kus, B. (2012). Financialisation and income inequality in OECD nations: 1995-2007. The. Economic and Social Review 43(4, Winter), 477-495.

Lazonick, William (2010) “Innovative business models and varieties of capitalism: Financialization of the US corporation.” Business History Review 84.4: 675-702.

Lazonick, William (2014) “Profits without prosperity.” Harvard Business Review 92.9: 46-55.

Lazonick, W., Shin, J.-S. (2019). Predatory Value Extraction: How the Looting of the Business. Corporation Became the US Norm and How Sustainable Prosperity Can Be Restored. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lee, C. H., Lee, K., Lee, K. (2002). Chaebols, financial liberalization and economic crisis: transformation of quasi-internal organization in Korea. Asian Economic Journal 16(1), 17-35.

Lee, Keun (2016). ECONOMIC CATCH-UP AND TECHNOLOGICAL LEAPFROGGING: THE PATH TO DEVELOPMENT AND MACROECONOMIC STABILITY IN KOREA, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Lee, Keun., Kim, B.Y., Park, Y.Y. and Sanidas, E. (2013), “Big Businesses and Economic Growth: Identifying a Binding Constraint for Growth with Country Panel Analysis,” Journal of Comparative Economics, 41 (2): 561-582.

Lee, Keun, Ginil Kim, Hong Kee Kim, and Hong-Sun Song, 2010, New Macro-Financial System for a Stable and Crisis-resilient Growth in Korea, Seoul Journal of Economics 23 (2): 145-186

Lee, K, and H. Shin. (2019). “Varieties of capitalism and East Asia: Long-term evolution, structural change, and the end of East Asian capitalism,” STRUCTURAL CHANGE AND ECONOMIC DYNAMICS, published online.

Lee, K, H.C. Shin, and J. Lee (2020), “From Catch-up to Convergence? Re-casting the Trajectory of Capitalism in South Korea, KOREAN STUDIES.

Lin, K.-H., Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2013). Financialization and US income inequality, 1970–2008. American Journal of Sociology 118(5), 1284-1329.

Nayyar, Deepak (Ed.) (2019). Asian Transformations: An inquiry into the Development of Nations, UNU-WIDER Studies in Development Economics, ISBN 978-0-19-884493-8, Oxford University Press.

Ostry, J.D., Ghosh, A.R., Habermeier, K., Chamon, M., Qureshi, M.S. and Reinhardt, D.B.S. (2010) Capital inflows: the role of controls. IMF Staff Position Note SPN/10/04.

Popov, Vladimir (2020). Which economic model is more competitive? The West and the South after the Covid-19 pandemic. Working paper.

Shin, H and K. Lee (2019), Impact of Financialization and Financial Development on Inequality: Panel Cointegration Results using OECD Data,” Asian Economic Papers

Shin, J.S, and H.J Chang (2003). RESTRUCTURING KOREA INC., London and New York: Routledge Curzon.

Soskice, D. W., and P. A. Hall. (2001) VARIETIES OF CAPITALISM: THE INSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS OF COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stabilini, A. (2015), “Revision of the Shareholders Rights Directive: It’s a Long Way Home”, Lexology.

Stockhammer, E. (2013). Why have wage shares fallen? ILO, Conditions of Work and. Employment Series 35(61), 1-61.