Archive

Can Democracy Reduce Inequality

Despite two decades of social policies targeting poverty and inequality, Latin America remains one of the most economically unequal regions in the world. Recurrent protests motivated by economic grievances have been a regular reminder of this reality. The ongoing health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic has disproportionately harmed already vulnerable populations, undoing some of the progress made. At the same time, democracy has taken root in the region, and participation in elections is growing. Then why hasn’t democracy been more effective in resolving Latin America’s persistent inequality?

Research shows voters are not able to make their demands for greater redistribution heard, while governments are not implementing redistributive policies at the desired pace. Reasons include unequal political participation, institutional bias against redistribution, and vote buying. Until such impediments are removed, democracy’s impact on inequality will remain limited.

Between 2000 and 2018, income inequality in Latin America, as measured by the Gini index, gradually fell from 53.3 to 45.7. During the same period, government spending on social protection steadily increased by almost one percentage point of GDP. While these trends seem promising, inequality in Latin America remains high and social spending low by the standards of more advanced economies. For example, the thirty-six countries of the OECD reported a Gini index of only 33.2 in 2018. That is puzzling, given that at least on paper, Latin America is built on similar economic and political principles—market economies and representative democracies. One would expect that the democratic process, which by design is based on the egalitarian principle of “one person, one vote”, would lead to policies that reduce market inequalities. In other words, in a well-functioning democracy, inequality should to some extent be self-correcting. Why isn’t this happening to a greater degree in Latin America?

Weak Voter Demand for Policies that Lower Inequality

A first explanation is that voter demand for inequality-reducing policies remains relatively weak. Lack of voter pressure can be seen in limited and unequal political participation. Despite the widespread use of compulsory voting, voter turnout in the region has remained below 70% on average. More importantly, turnout is biased in a way that is detrimental to the poor, as voting is less common among the less educated and the less wealthy.

Even when they do vote, the less well-off are less informed, and thus less effective in choosing candidates that represent their economic interests. The poor are the greatest beneficiaries of basic public services, such as public education and health care. Unfortunately, voter demand for government investments in these public goods is tenuous, either due to low trust in the ability of public officials to spend public resources in these areas effectively, or due to a preference for immediate benefits such as cash transfers, at the expense of longer-term benefits such as high-quality education and public safety.

Weak Supply of Policies Designed to Reduce Inequality

A second explanation is that the policymaking process may fail to internalize popular demand for redistribution. In some cases, this occurs because political institutions can be manipulated by incumbents to retain power, for example through legislative malapportionment. Others argue that elements of the elite gain access to and remain in power using campaign donations from narrow interest groups, obviating the need to rely on broad popular support.

More recent research has shown that vote buying by political candidates, a prevalent phenomenon in many Latin American democracies, subverts the normal functioning of the budget process. Voters targeted with vote buying prior to an election may receive no government benefits after the election. As poorer voters are more susceptible to vote buying, they are often left unrepresented in the subsequent negotiations over the budget. Thus, vote buying crowds out redistributive spending that could reduce inequality.

Stronger Democracies Better Alleviate Inequality

In a chapter of the recent IDB report entitled The Inequality Crisis I present new data patterns that support the idea that the strength of democracy matters for the alleviation of inequality. I use the Economist Intelligence Unit democracy index to rank democratic quality along five dimensions. Among Latin American countries, stronger democracies provide more redistributive spending. At one end of the spectrum, Nicaragua spends less than 1% of GDP on social protection, compared to almost 7% in Uruguay, at the other end of the spectrum. Interestingly, stronger democracies are also characterized by higher voter turnout and fewer protests. This suggests that voting, rather than protesting, is a catalyst for government redistribution. Protests appear to be a symptom of unmet economic expectations.

Some development institutions, such as the UNDP, have suggested that inequality may be one of democracy’s greatest weaknesses. As the less well-off are economically marginalized, they become more disengaged with the democratic process. However, a weaker democracy may also fail to alleviate inequality. Overcoming this vicious circle remains a challenge for Latin America’s young democracies. Political and civic leaders in the region should renew their commitment to strengthening democratic institutions, chief among them free elections, civic liberties, and independent media. Over time, better-functioning democracies should improve economic equity. Democracy can certainly reduce inequality, as long as it functions as intended.

How Inequality Undermines Democracy?

Inequality has been on the rise over the last three decades, and has been a pervasive issue in the recent U.S. national election. On one level, income inequality is a non-issue in a market economy where there will always be winners and losers. In a market where individuals are free to make choices and reap the rewards of the choices they make, it is a given that some will wind up with more than others. We cannot all be equal because we don’t all have the same natural endowments. Those with certain skills and abilities will often wind up with more than those without. And those who went to school to train for specific occupations that pay well will earn more than those who did not. In short, skilled workers will earn more than non-skilled workers. Consequently, in an increasingly global economy where there will be two classes — skilled and educated workers at the top earning high wages and unskilled and poorly educated workers at the bottom earning low wages — there is bound to be inequality. Moreover, as these trends continue, the gap between the top and the bottom is only bound to grow. On another level, however, income inequality is a seminal issue because of what it really speaks to: the disappearance of the middle class. Inequality per se may not be the problem; rather it is the rate of increase in inequality. In this essay, I argue that to the extent that inequality effectively speaks to a shrinking middle class it represents a threat to democracy.

Rising Inequality

Income inequality is an amorphous concept. When we talk about income inequality we are often talking about the gap between the top and the bottom. The extent to which it is a problem is contingent on just how it is measured. General income inequality, as measured by the ratio of the incomes of the top fifth of the population to those of the bottom fifth, for instance, includes in all income; not just income earned laboring. For those at the top this can include wages, interest and dividend income.[i] For those at the bottom this can include income supports, which are usually subsidies or in-kind assistance that has the effect of boosting the wages of those at the bottom or their effective purchasing power. Income at the bottom, then, often includes wages plus these supports, whether through public assistance transfer programs and/or disability programs. Therefore, wage income will not be the same as income inequality, and this gap between the top and bottom will tend to be less.

General income inequality has in recent decades been on the rise. Those at the top of the distribution have seen their incomes increase while those at the bottom have seen their incomes decrease in real terms. Prior to 1973, the incomes of families in the bottom fifth of the income distribution in the U.S. grew more rapidly than the income of families in other countries. After 1973 low-income families in the U.S. experienced a steady decline in real income, especially from the late 1970s through the middle of the 1990s. Between 1979 and 2007, the top one percent of families had 60 percent of the income gains while the bottom 90 percent only had about 9 percent of those income gains (Belman and Wolfson 2014). Income inequality, especially after 1980, exploded with the top decile share of the national income rising to between 45-50 percent in the 2000s. This may nonetheless understate the problem, which in recent years has been couched as the very top pulling away from the rest because a subclass of “supermanagers” — those at the top of the distribution with great ability and talent, who in some cases were viewed as “superstars” because they were able to make their companies profitable and return a high rate of return to shareholders — emerged who were earning extremely high compensation (Hacker and Pierson 2010; Piketty 2014).

The Threat to Democracy

Democratic theory assumes a society of free, equal, and autonomous individuals. Although democracy may have different meanings for different people, an ideal of democracy is that all individuals are supposed to have equal standing. This means that each individual is equal before the law, has the same vote as other individuals, the same right to express oneself in the political sphere, and perhaps most importantly the same potential to influence what government does, even if they opt not to exercise that potential. All citizens, then, have the same access to governing institutions. Within this theoretical construct, which may also characterize American democracy, money is supposed to be irrelevant to one’s standing. Both the rich and the poor are equal before government (Hacker and Pierson 2010). This conception of equality, otherwise known as procedural equality is not usually concerned with how resources, wealth and income are distributed, but with how individuals stand in relation to one another. Individuals can have more than others so long as they are equal in terms of their legal and political standing. Procedural equality is especially critical to democratic society because it serves to secure another essential condition: personal freedom, which is also a necessary condition for individuals to function autonomously. The greater their autonomy, the more likely they are to participate in the democratic process. Individuals are free to pursue their goals and objectives—i.e. self-interests—so long as their pursuit does not interfere with others’ ability to pursue their own goals and objectives. In a very basic sense, and certainly within the context of classical political thought, this is what it means to talk about personal independence or autonomy. But as Tocqueville observed there cannot be real political equality without some measure of economic equality as well, because a society with great concentrations of poor people can be dangerous (Zetterbaum 1987). Therefore, economic inequality could pose serious problems in a procedural democracy.

Why, then, might inequality be so dangerous to democracy? According to Acemoglu and Robinson (2006), unrest is often a consequence of inequality. And yet, changes are more likely to occur in those societies with greater inequality between elites and citizens. The more equals the society, the less likely are the masses to demand democratization. Democratization requires that society be sufficiently unequal so that the threat of revolution is credible. Therefore, elite may be willing to begin a transition by extending the right of franchise because it is in its interests to do so. The transition effectively preserves the status quo by staving off the threat of revolution, which in the end may preserve the power base of the elite. Yet, the elite only democratizes to the degree necessary to stave off the threat of revolution, because the former effectively limits the power of the majority by diluting popular pressure and undermining the power of the majority. Democratization refers to achieving voice through fair procedures. But democratization could mean achieving greater equality through the redistribution of resources aimed at achieving equality of result.

Economic equality, then, effectively promotes democracy because it effectively reduces the pressure for redistribution, which could occur as a byproduct of mass revolution and the subsequent creation of an authoritarian regime (Boix 2003). More unequal distribution of wealth increases the redistributive demands of the population and the ultimate level of taxes in a democratic system. But what happens when the political system is unresponsive to a so-called democratic vote on the tax rate?

A truly democratic regime would not simply take away from the wealthy elite for the benefit of the masses, but it might set a higher tax rate for purposes of redistribution. In a democracy, everybody votes on the tax rate in accordance with what is known as the median voter theorem. This holds that the more inequality there is the greater will be the distance between the median income and society’s average income. The greater the distance, the more calls there are for redistribution, and it is the distance itself that effectively determines the tax rate (Meltzer and Richard 1981).

On an individual level, unequal distribution of wealth and income, however, may adversely affect individuals’ ability to participate in the democratic process as equals. It may result in procedural inequality to the extent that those lacking in wealth and income may not enjoy the same access to political and policy officials as those who possess wealth and income enjoy. With a greater concentration of wealth at the top, elites are in a better position to use their wealth toward the attainment of their political and other ideological objectives (Bachrach and Botwinick 1992: 4-5). Those at the top of the distribution often enjoy inordinate power and are able to not only limit redistribution, but shape the rules of the game in favor of those with more resources (Stiglitz 2012). Various studies have found legislative bodies to be more responsive to affluent constituents than to non-affluent constituents (Bartels 2008; Gilens 2012; Volscho and Kelly 2012).

Inequality, especially in its extreme form of poverty, does in the end deprive us of our capabilities, which is said to be a kind of freedom. To the extent that individuals at the bottom of the income distribution could be said to be poor, poverty deprives individuals of their capabilities. Therefore, there is a strong case to be made for judging individual advantage in terms of the capability that a person has — “the substantive freedoms he or she enjoys to lead the kind of life he or she has reason to value” (Sen 1999, p.87). Such freedoms are the basis of individual autonomy. Those with more resources may be better positioned to pursue their goals and objectives, while those with fewer resources may find that their ability to pursue their goals and objectives are limited.

An individual’s ability to pursue their goals and objectives is important to democracy for yet another reason. A democracy, especially as its legitimacy and power are derived from popular consent, assumes that individuals have the capacity to reason for themselves, i.e. to deliberate in the public square, and to act on that capacity in a responsible manner. They cannot effectively participate, whether it be in full policy discussions or selecting their own representatives, if they cannot deliberate in a rational manner. As democracy requires that individuals execute their agency, human agency must be protected. But this human agency also presupposes that basic material needs will have been met, which may be less likely given ever widening disparities in wealth and income. Democracy also requires a measure of trust between people, and growing income inequality is said to threaten trust as various groups, mainly those at the bottom, experience political alienation and perceive the system not to be fair. As social capital is the glue that holds society together (Stiglitz 2012), if individuals believe that the economic and political system is unfair, the glue does not work and society does not function well. This is because institutions effectively promote trust. A trusting population tends to be more cooperative, and governments with trusting populations tend to be less corrupt and function with less conflict and greater responsiveness (Uslaner 2008).

Impact of Inequality on Civic Participation

Income inequality not only distorts democracy in terms of how institutions and political actors respond to different levels of income, but it may have a profound effect on the development of social capital, which affects civic engagement. Democracy requires the active participation of citizens in the affairs of their communities, which extends beyond mere voting. Underlying social capital is the notion that civic virtue is most powerful when it is embedded in a dense network of social relations. American civil society has been defined by its associative life, in which Americans belong to voluntary organizations. And through these organizations, they participate in the affairs of their communities (Putnam 2000).

In a study of the relationship between income inequality and civic engagement, Levin-Waldman (2013) found that in 2008 individuals in households with different levels of income had different levels of civic engagement. Six measures of civic engagement were considered: daily discussions of politics, daily reading of newspapers — which were intended to speak to one’s knowledge about and interest in politics — involvement in protests, attendance at political meetings, visiting public officials, and participating in civic organizations. Participation was found to be greater on all measures of participation among those in households earning more than $100,000 a year than among those earning less than $30,000. Those at the highest end of the distribution were not necessarily more likely to be engaged than those between $30,000 and $99,999, but those in households between $30,000 to $59,999 were considerably more likely to be engaged than those in households below $30,000. Participation appeared to improve dramatically when one was in a household with income greater than $30,000. These differences alone would suggest that entry into the middle class might result in greater levels of civic participation. Moreover, logistical regressions found that those with higher incomes were more likely to be civically engaged, and that those earning less than a minimum wage were least likely to be engaged.

Aside from the adverse impact that income inequality has on civic engagement, it could also lead to political anomie. As family income inequality increases, those families below the median are further from the social norm than before. Similarly, those at the top of the distribution see a larger gap between themselves and the rest of the population. Families at the bottom of the distribution may end up drifting further from the mainstream, and thus may also experience greater alienation as those with greater resources may come to see them as both more distinct and undeserving. This may also have consequences for how citizens in turn view the potential role and functions of government (Haveman, Sandefeur, Wolfe, and Voyer 2004). Poor people experience greater social alienation because of their tendency to participate less, which means that they may be out of touch with common interests. But participation is also less likely because the alienation coming from social isolation will lead many to the conclusion that there really is no benefit from participation in the common project of which they are part. When resources are unequally distributed, those at the top and the bottom might not see themselves as sharing the same fate. Consequently, they have less reason to trust people of different backgrounds. Where inequality is high, people may be less optimistic about being masters of their own fate. Increasing inequality results in less participation because of declining trust (Uslaner and Brown 2005).

Conclusion

With rising inequality, it ought to be clear that there are serious challenges to democracy. It cannot be predicted with certainty just how disruptive inequality will be to democracy, as this is contingent on the fragility of democracy. In the U.S., we are clearly seeing an erosion in democracy in that elected representatives no longer represent all people equally. Rather there is greater responsiveness to those with resources, especially those contributing to political campaigns. Increasingly those without resources find themselves frozen out. In more fragile democracies, the response is unrest. And even in the U.S. we see some of that with various social protest movements. Although the results of the 2016 national election were not necessarily a response to rising income inequality, they were clearly a response to the larger economic conditions of which rising income inequality has been a symptom. Specifically, voters appeared to be rebelling against political elites who apparently were unable to deliver good job growth with rising wages. Voters chose a candidate who, rhetorically at least, was opposed to open borders and free trade, and were effectively challenging the commitment of elites to globalism — the same globalism that has resulted in the two-tier economy with highly skilled and paid workers at the top and poorly skilled and paid workers at the bottom. It might be a stretch to conclude that the election of Donald Trump represents a desire for authoritarianism. And yet, his critics view him as such, and if the voters were not choosing what they might have thought were authoritarian solutions to economic conditions, they were clearly responding to the very economic conditions that have been the source of rising inequality in recent years.

Notes and References

[i] Dividend income is income from stocks and/or other types of investments.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. 2006. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bachrach, Peter and Aryeh Botwinick. 1992. Power and Empowerment: A Radical Theory of Participatory Democracy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Bartels, Larry M. 2008. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Belman, Dale and Paul J. Wolfson. 2014. What Does the Minimum Wage Do? Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Boix, Carles. 2003. Democracy and Redistribution. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gilens, Martin. 2012. Affluence & Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton and New York: Princeton University Press/Russell Sage Foundation.

Hacker, Jacob S. & Paul Pierson. 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer — And Turned its Back on the Middle Class. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Haveman, Robert, Gary Sandefeur, Barbara Wolfe, and Andrea Voyer. 2004. “Trends in Children’s Attainments and Their Determinants as Family Income Inequality Has Increased.” in Kathryn Neckerman ed., Social Inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Levin-Waldman, Oren M. 2013. “Income, Civic Participation and Achieving Greater Democracy. Journal of Socio-Economics. 43,2:83-92.

Meltzer, Alan H. and Scott F. Richard. 1981. “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government.” Journal of Political Economy. 89,5: 914-927.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2012. The Price of Inequality. New York: W.W. Norton.

Uslaner, Eric. 2008. “The Foundations of Trust: Macro and Micro.” Cambridge Journal of Economics. 32:289-294.

—————– and Mitchell Brown. 2005. “Inequality, Trust, and Civic Engagement.” American Politics Research. 33,6 (November):868-894.

Volscho, Thomas W. Jr. and Nathan J. Kelly. 2012. “The Rise of the Super-Rich: Power Resources, Taxes, Financial Markets, and the Dynamics of the Top 1 Percent, 1949-2008.” American Sociological Review. 77,5:679-699.

Zetterbaum, Marvin. 1987. “Alexis De Tocqueville.” In Leo Strauss and Joseph Cropsey eds., History of Political Philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Introducing Kuznets Waves: How Income Inequality Waxes and Wanes over the Very Long Run

The Kuznets curve was widely used to describe the relationship between growth and inequality over the second half of the 20th century, but it has fallen out of favour in recent decades. This column suggests that the current upswing in inequality can be viewed as a second Kuznets curve. It is driven, like the first, by technological progress, inter-sectoral reallocation of labour, globalization, and policy. The author argues that the US has still not reached the peak of inequality in this second Kuznets wave of the modern era.

In 1955 when Simon Kuznets wrote about the movement of inequality in rich countries (and a couple of poor ones), the US and the UK were in the midst of the most significant decrease of income inequality ever registered in history, coupled with fast growth. It thus seemed eminently reasonable to look at the factors behind the decrease of inequality, and Kuznets famously found them in expanded education, lower inter-sectoral productivity differences (thus the rent component of wages would be equalized), lower return to capital, and political pressure for greater social transfers. He then looked at (or rather imagined) the evolution of inequality during the previous century and thought that, driven by the transfer of labour from agriculture to manufacturing, inequality rose and reached its peak in the rich world sometime around the turn of the 20th century. Thus, he created the famous Kuznets curve.

The Kuznets curve was the main tool used by inequality economists when thinking about the relationship between development or growth and inequality over the past half century. But the Kuznets curve gradually fell out of favor because its prediction of low inequality in very rich societies could not be squared with the sustained increase in income inequality that started in the late 1970s in practically all developed nations (see the long-run graphs for the US and the UK). Many people thus rejected it.

The Upswing in Current Inequality as a Second Kuznets Curve

In a new book (Milanovic 2016), I argue however that we should see the current upswing in inequality as the second Kuznets curve in the modern times, being driven, like the first, mostly by a technological revolution and the transfer of labour from more homogenous manufacturing into skill-heterogeneous services (and thus producing a decline in the ability of workers to organize), but also (again like the first) by globalization, which has both led to the famous hollowing out of the middle classes in the west and to a pressure to reduce high tax rates on mobile capital and high-skilled labour. The elements listed here are not new. But putting them together (especially viewing technological progress and globalization as practically indissoluble, even if conceptually different) and viewing this as part of regular Kuznets waves is new. It has obvious implications for the future, not the least that this bout of inequality growth will peak like the previous one and eventually go down.

But before I address that part, let us consider recent important work done by economic historians such as van Zayden (1995); Nogal and Prados (2013); Alfani (2014) and Ryckbosch (2014), who have documented periods of waxing and waning inequality in pre-modern Europe. The interesting part is that Kuznets cycles in pre-modern societies basically replicate the Malthusian cycles because they take place in conditions of quasi-stationary mean income. The pre-modern Kuznets cycles are not driven by economic factors but by epidemics and wars. Both lead to a decrease in population, an increase in mean income, higher wages (because of labour scarcity) and thus lower inequality, that is, until population growth in a Malthusian fashion reverses all these gains.

Thus, we can observe Kuznets waves over some six or seven centuries of European history. In pre-modern times, they are observable against time because mean income is more or less constant (it is just one point on the x-axis). After the Industrial Revolution, however, we see the waves responding to economic factors (e.g. technological change, transfer of labour), and can plot them as Kuznets thought against mean income. This is shown here in the graphs for the US and the UK (Figure 1 and 2). In addition, I show in my book long-term inequality cycles for Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, Japan, Brazil, Chile, and over a shorter period for China.

While Kuznets’ explanation was focused almost entirely on economic and thus ‘benign’ forces, he was wrong to overlook the impact of ‘malign’ forces (especially wars) that are powerful engines of income equalisation. I find this somewhat puzzling because Kuznets himself, having worked during World War II in the US Bureau of Planning and Statistics, must have noticed how the war led to the compression of income through higher taxation, financial repression, rationing, price controls, and even sheer destruction of physical assets (as in Europe and Japan).

Inequality May Not Be Overturned Soon

Which leads us to the present. How long will the current upswing of the Kuznets wave continue in the rich world, and when and how will it stop? I am skeptical that it will be overturned soon, at least not in the US where I see four powerful forces that keep on pushing inequality up. I will just list them here (they are, of course, discussed in the book):

- Rising share of capital income which is in all rich countries extremely concentrated among the rich (with a Gini in excess of 90);

- Growing association of high incomes from both capital and labour in the hands of the same people (Atkinson and Lakner 2014);

- Homogamy (the educated and the rich marrying each other); and

- Growing importance of money in politics which allows the rich to write rules favourable to them and thus to maintain the inequality momentum (Gilens 2012).

The peak of inequality in the second Kuznets wave should be lower than in the first (when in the UK, it was equal to the inequality level of today’s South Africa) because the rich societies have in the meantime acquired a number of ‘inequality stabilizers’, from unemployment benefits to state pensions.

The pro-inequality trends will be very hard to overturn during the next generation, but eventually they may be – through a combination of political change, pro-unskilled labour technological innovations (which will become more profitable as skilled labor’s price increases), dissipation of rents acquired during the current bout of technological efflorescence, and possibly greater attempts to equalize ownership of assets (through forms of ‘people’s capitalism’ and workers’ shareholding).

Now, these are of course the benign factors that, I think, will ultimately set inequality in rich countries on its downward path. But history teaches us too that there are malign factors, notably wars, in turn caused by domestic maldistribution of income and power of the elites (as was the case in the World War I), that can also do the job of income levelling. But they do it at the cost of millions of human lives. One can hope that we have learned something from history and would avoid this destructive path to equality in poverty and death.

References

Alfani, G (2014), “Economic inequality in the northwestern Italy: a long-term view (fourteenth to eighteenth century)”, Dondena Working Paper No. 61, Bocconi University, Milano.

Alvarez-Nogal, C and L Prados de la Escosura (2013), “The rise and fall of Spain (1270–1850),” Economic History Review, vol. 66(1), pages 1-37.

Atkinson, A and C Lakner (2014), “Wages, capital and top incomes: The factor income composition of top incomes in the USA, 1960-2005”, November version.

Gilens, M(2012), Affluence and Influence, Princeton University Press.

Kuznets, S (1955), “Economic growth and income inequality”, American Economic Review, March, pp. 1-28.

Milanovic, B (2016), Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization, Harvard University Press.

Ryckbosch, W (2014), “Economic inequality and growth before the Industrial Revolution: A case study of Low countries (14th-16th century), Dondena Working Paper No. 67, Bocconi University, Milano.

van Zanden, J L (1995), “Tracing the beginning of the Kuznets curve: western Europe during the early modern period”, The Economic History Review, vol. 48, issue 4, pp. 1-23. November.

Wealth and Income Distribution: New Theories Needed for a New Era

Growth theories traditionally focus on the Kaldor-Kuznets stylised facts. Ravi Kanbur and Nobelist Joe Stiglitz argue that these no longer hold; new theory is needed. The new models need to drop competitive marginal productivity theories of factor returns in favour of rent-generating mechanism and wealth inequality by focusing on the ‘rules of the game.’ They also must model interactions among physical, financial, and human capital that influence the level and evolution of inequality. A third key component will be to capture mechanisms that transmit inequality from generation to generation.

Six decades ago, Nicholas Kaldor (1957) put forward a set of stylized facts on growth and distribution for mature industrial economies. The first and most prominent of these was the constancy of the share of capital relative to that of wealth in national income. At about the same time, Simon Kuznets (1955) put forward a second set of stylized facts — that while the interpersonal inequality of income distribution might increase in the early stages of development, it declines as industrialized economies mature.

These empirical formulations brought forth a generation of growth and development theories whose object was to explain the stylised facts. Kaldor himself presented a growth model which claimed to produce outcomes consistent with constancy of factor shares, as did Robert Solow. Kuznets also developed a model of rural-urban transition consistent with his prediction, as did many others (Kanbur 2012).

Kaldor-Kuznets Facts No Longer Hold

However, the Kaldor-Kuznets stylized facts no longer hold for advanced economies. The share of capital as conventionally measured has been on the rise, as has interpersonal inequality of income and wealth. Of course, there are variations and subtleties of data and interpretation, and the pattern is not uniform. But these are the stylized facts of our time. Bringing these facts centre stage has been the achievement of research leading up to Piketty (2014).

It stands to reason that theories developed to explain constancy of factor shares cannot explain a rising share of capital. The theories developed to explain the earlier stylized facts cannot very easily explain the new trends, or the turnaround. At the same time, rising inequality has opened once again a set of questions on the normative significance of inequality of outcomes versus inequality of opportunity. New theoretical developments are needed for positive and normative analysis in this new era.

What sort of new theories? In the realm of positive analysis, Piketty has himself put forward a theory based on the empirical observation that the rate of return to capital, r, systematically exceeds the rate of growth, g; the famous r > g relation. Much of the commentary on Piketty’s facts and theorizing has tried to make the stylized fact of rising share of capital consistent with a standard production function F (K, L) with capital ‘K’ and labour ‘L’. But in this framework a rising share of capital can be consistent with the other stylised fact of rising capital-output ratio only if the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour is greater than unity, which is not consistent with the broad empirical findings (Stiglitz, 2014a). Further, what Piketty and others measure as wealth ‘W’ is a measure of control over resources, not a measure of capital K, in the sense that that is used in the context of a production function.

Differences between K and W

There is a fundamental distinction between capital K, thought of as physical inputs to production, and wealth W, thought of as including land and the capitalized value of other rents which give command over purchasing power. This distinction will be crucial in any theorizing to explain the new stylized facts. ‘K’ can be going down even as ‘W’ increases; and some increases in W may actually lower economic productivity. In particular, new theories explaining the evolution of inequality will have to address directly changes in rents and their capitalized value (Stiglitz 2014). Two examples will illustrate what we have in mind.

- Consider first the case of all sea-front property on the French Riviera.

As demand for these properties rises, perhaps from rich foreigners seeking a refuge for their funds, the value of sea frontage will be bid up. The current owners will get rents from their ownership of this fixed factor. Their wealth will go up and their ability to command purchasing power in the economy will rise correspondingly. But the actual physical input to production has not increased. All else constant, national output will not rise; there will only be a pure distributional effect.

- Consider the case where the government gives an implicit guarantee to bail out banks.

This contingent support to income flows from ownership of bank shares will be capitalised into the value of these shares. Of course, there is an equal and opposite contingent liability on all others in the economy, in particular on workers — the owners of human capital. Again, without any necessary impact on total output, the political economy has created rents for share owners, and the increase in their wealth will be reflected in rising inequality. One can see this without going through a conventional production function analysis. Of course, the rents once created will provide further resources for rentiers to lobby the political system to maintain and further increase rents. This will set in motion a spiral of increasing inequality, which again does not go through the production system at all — except to the extent that the associated distortions represent a downward shift in the productivity of the economy (at any level of inputs of ‘K’ and labour).

Analysing the role of land rents in increases in inequality can be done in a variant of standard neoclassical models — by expanding inputs to include land; but explaining increase in inequality as a result of an increase in other forms of rent will need a theory of rents which takes us beyond the competitive determination of factor rewards.

Differences in Inequality: Capital Income versus Labour Income

The translation from factor shares to interpersonal inequality has usually been made through the assumption that capital income is more unequally distributed than labour income. Inequality of capital ownership then translates into inequality of capital income, while inequality of income from labour is assumed to be much smaller. The assumption is made in its starkest form in models where there are owners of capital who save and workers who do not.

These stylised assumptions no longer provide a fully satisfactory explanation of income inequality because: (i) there is more widespread ownership of wealth through life cycle savings in various forms including pensions; and (ii) increasingly unequal returns to increasingly unequally distributed human capital has led to sharply rising inequality of labour income.

Sharply rising inequality of labour income focuses attention on inequality of human capital in its most general sense:

- Starting with unequal prenatal development of the foetus;

- Followed by unequal early childhood development and investments by parents;

- Unequal educational investments by parents and society; and

- Unequal returns to human capital because of discrimination at one end and use of parental connections in the job market at the other end.

Discrimination continues to play a role, not only in the determination of factor returns given the ownership of assets, including human capital; but also on the distribution of asset ownership.

- At each step, inequality of parental resources is translated into inequality of children’s outcomes.

An exploration of this type of inequality requires a different type of empirical and theoretical analysis from the conventional macro-level analysis of production functions and factor shares (Heckman and Mosso, 2014, Stiglitz, 2015).

In particular, intergenerational transmission of inequality is more than simple inheritance of physical and financial wealth. Layered upon genetic inequalities are the inequalities of parental resources. Income inequality across parents, due to inequality of income from physical and financial capital on the one hand, and inequality due to inequality of human capital on the other, is translated into inequality of financial and human capital of the next generation. Human capital inequality perpetuates itself through intergenerational transmission just as wealth inequality caused by politically created rents perpetuates itself.

Given such transmission across generations, it can be shown that the long-run, ‘dynastic’ inequality will also be higher (Kanbur and Stiglitz 2015). Although there have been advances in recent years, we still need fully developed theories of how the different mechanisms interact with each other to explain the dramatic rises in interpersonal inequality in advanced economies in the last three decades.1

High Inequality: New Realities and Old Debates

The new realities of high inequality have revived old debates on policy interventions and their ethical and economic rationale (Stiglitz 2012). Standard analysis which balances the tradeoff between efficiency and equity would suggest that taxation should now become more progressive to balance the greater inherent inequality against the incentive effects of progressive taxation (Kanbur and Tuomala,1994 ).

One counter argument is that what matters is not inequality of ‘outcome’ but inequality of ‘opportunity’. According to this argument, so long as the prospects are the same for all children, the inequality of income across parents should not matter ethically. What we should aim for is equality of opportunity, not income equality. However, when income inequality across parents translates into inequality of prospects across children, even starting in the womb, then the distinction between opportunity and income begins to fade and the case for progressive taxation is not undermined by the ‘equality of opportunity’ objective (Kanbur and Wagstaff 2015).

Concluding Remarks

Thus, the new stylised facts of our era demand new theories of income distribution.

- First, we need to break away from competitive marginal productivity theories of factor returns and model mechanisms which generate rents with consequences for wealth inequality.

This will entail a greater focus on the ‘rules of the game.’ (Stiglitz et al 2015).

- Second, we need to focus on the interaction between income from physical and financial capital and income from human capital in determining snapshot inequality, but also in determining the intergenerational transmission of inequality.

- Third, we need to further develop normative theories of equity which can address mechanisms of inequality transmission from generation to generation.2

References

Bevan, D and J E Stiglitz (1979), “Intergenerational Transfers and Inequality”, The Greek Economic Review, 1(1), August, pp. 8-26.

Heckman, J and S Mosso (2014), “The Economics of Human Development and Social Mobility”, Annual Reviews of Economics, 6: 689-733.

Kaldor, N (1957), “A Model of Economic Growth”, The Economic Journal, 67(268): 591-624.

Kanbur, R (2012), “Does Kuznets Still Matter?” in S. Kochhar (ed.), Policy-Making for Indian Planning: Essays on Contemporary Issues in Honor of Montek S. Ahluwalia, Academic Foundation Press, pp. 115-128, 2012.

Kanbur, R and J E Stiglitz (2015), “Dynastic Inequality, Mobility and Equality of Opportunity“, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 10542.

Kanbur, R and M Tuomala (1994), ‘‘Inherent Inequality and the Optimal Graduation of Marginal Tax Rates”, (with M. Tuomala), Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 96, No. 2, pp. 275-282, 1994.

Kuznets, S (1955), “Economic Growth and Income Inequality”, The American Economic Review, 45(1): 1-28.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Piketty, T, E Saez, and S Stantcheva (2011), “Taxing the 1%: Why the top tax rate could be over 80%”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Roemer, J E and A Trannoy (2014), “Equality of Opportunity”, in A B Atkinson and F Bourguignon (eds.) Handbook of Income Distribution SET Vols 2A-2B. Elsevier.

Stiglitz, J E, et. al. (2015) “Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy“, Roosevelt Institute.

Stiglitz, J E (1969), “Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, Econometrica, 37(3), July, pp. 382-397. (Presented at the December 1966 meetings of the Econometric Society, San Francisco.)

Stiglitz, J E (2012), The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, New York: W.W. Norton.

Stiglitz, J E (2014), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, paper presented to the International Economic Association World Congress, Dead Sea, June and forthcoming in Inequality and Growth: Patterns and Policy, Volume 1: Concepts and Analysis, to be published by Palgrave MacMillan.

Stiglitz, J E (2015), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals: Parts I-IV”, NBER Working Papers 21189-21192, May.

Footnotes

1 For early discussions of such transmission processes, see Stiglitz(1969) and Bevan and Stiglitz (1979).

2 Developments in this area are exemplified by Roemer and Trannoy (2014).

Income Inequality and Citizenship: Quantifying the Link

Our level of income is unarguably dependent on where we live in the world. But evidencing this is tricky. This Posting presents a model that explains global income variability using one variable only – where you live. The results suggest that we might want to reassess how we think about both economic migration and global inequality of opportunity.

It is as obvious as it is well known that the world is unequal in terms of individuals’ incomes (e.g. Mohammed 2015). But it is unequal in a very particular way – when split into ‘inequality within countries’ and ‘inequality between countries’, the latter accounts for by far the biggest gap.

Inequality within countries measures, for instance, gaps between poor and rich Americans or between poor and rich Chinese. For simplicity, let’s call it ‘class’ inequality. But there is also another equally obvious inequality – that between rich and poor nations. More specifically, this inequality is measured as the gap between the ‘representative’ or ‘average’ individuals of any two countries, be they Morocco and Spain or Mexico and the US. For simplicity, let’s call this ‘locational’ inequality.

Inequality, as it is commonly understood in today’s world, is such that whatever measure we choose, the lion’s share of global inequality is ‘explained’ by the differences in mean incomes between countries.

This was not always the case. Although our data for the past are far more tentative than our data for today’s global income distribution, we can still state with little doubt that the dominant type of equality in the 19th century was that within countries (see Milanovic 2011).

Citizenship Premiums and Penalties

If income differences between countries are large then your income will significantly depend on where you live, or even on where you were born (97% of the world’s population remain in the countries where they were born). This is what I call a ‘citizenship premium’ (or a ‘citizenship penalty’) – a ‘rent’ that a person receives if he or she happens to be born in a rich country, or, if we use the terminology introduced by John Roemer, an ‘exogenous circumstance’ which is independent from any one individual’s effort and episodic luck (Roemer 2000).

How big is citizenship rent, how does it vary with one’s position in the income distribution, and what does it imply for global inequality of opportunity and migration?

Estimating Citizenship Rent

I estimate citizenship rent by using data collected from household surveys conducted in 118 countries in and around the year 2008 (Milanovic 2015). For each country, I have micro-level (household) data ordered into 100 percentiles, with individuals ranked by their household per capita income. This gives 11,800 country/percentiles with ‘representative’ per capita incomes expressed in dollars of equal purchasing parity, making incomes across countries comparable.

I ‘explain’ these incomes using only one variable – the country where individuals live. Of course, people living in the US will tend to have higher incomes at any given percentile of the distribution than people living in poor countries in, for instance, Africa. But how will it look for the world as a whole? In a least-square dummy variable regression, I use Congo (the poorest county in the world) as the ‘omitted country’ so that I can express the citizenship premium in every other country in terms of the income gain compared to Congo. The premium for the US is 355%, it is 329% for Sweden and 164% for Brazil. But for Yemen, another very poor country, it’s 32%.

According to this regression, we can explain more than two-thirds of the variability in incomes across country/percentiles by only one variable – the country where people live. This estimation shows that, as we thought, a lot of our income depends on where we live.

Citizenship Rent across the Distribution

But this is only an average premium that compares countries. Does citizenship rent vary along the entire income distribution? If I were to take into consideration only people belonging to the lowest part of the income distribution in each country, would the premium still be the same?

Intuition may help here. Suppose that I focus only on the incomes of the lowest decile (with rich countries more equal than poor countries). Then the gap between rich and poor countries should be greater for the very poor people than for the average individual. And this is indeed what we find – Sweden’s citizenship premium compared to Congo is now 367% versus 329% on average. But Brazil’s is 133% versus 164%. The situation at the top is exactly the opposite – Sweden’s advantaged position at the 90th percentile of the income distribution is ‘only’ 286%, but Brazil’s becomes 188%.

Implications for Migration

The existence of the citizenship premium has obvious implications for migration: people from poor countries will have the opportunity to double or triple their real incomes by moving to a rich country.

But the fact that the premium varies as a function of one’s position in the income distribution carries additional implications. If I consider moving to one of two countries that have the same average income, my decision on where to migrate – based on economic criteria alone – will also be influenced by my expectations regarding where I may end up in the recipient county’s income distribution. My decision will thus be influenced by the extent to which the recipient country’s income distribution is unequal.

Suppose that Sweden and the US have the same mean income. If I expect to end up in the bottom part of a recipient country’s distribution, then I should migrate to Sweden. The poor people in Sweden are better off compared to the mean, and the citizenship premium, evaluated at lower parts of distribution, is greater. The opposite conclusion follows if I expect to end up in the upper part of the recipient country’s distribution – I should migrate to the US.

This last result has unpleasant implications for rich countries with greater ‘in-country’ equality. More equal rich countries will tend to attract lower-skilled migrants who generally expect to be placed in the bottom part of the recipient country’s distribution. Developing a national welfare state would have the perverse effect of attracting migrants who can contribute less.

Even in this rough sketch, we also have to consider the levels of social mobility in recipient countries because more unequal countries with strong social mobility will, everything else being the same, tend to appeal to more skilled migrants.

Global Inequality of Opportunity

The mere existence of a large citizenship premium implies that there is no such a thing as global equality of opportunity because a lot of our income depends on the accident of birth.

So should we strive for global equality of opportunity or not? It is a political philosophy question that philosophers have thought much more about than economists. Some, following John Rawls in The Law of Peoples, believe that this is not an issue and that every argument for global equality of opportunity would conflict with the right of national self-determination. But other political philosophers like Thomas Pogge believe that in an interdependent world, the dominant role of chance in people’s life is not to be accepted lightly (Pogge 2008). I am not proposing a solution to this issue, yet, I believe that economists should not shy away from addressing it.1

As gaps between nations diminish, mostly thanks to the high growth rates of Asian countries, the citizenship rent will tend to reduce. But there is such a huge gap today that even a century of much higher growth in poor countries (in comparison to rich countries) will not eradicate citizenship rent.

However, it will reduce. As it does, it will also reduce overall global inequality. This might then lead us to a world not dissimilar to the mid-19th century, in which class is again more important for one’s global income position than location.

Do I hear the distant sound of Marx?

References

Milanovic, B (2011), The haves and the have-nots: a short and idiosyncratic history of global inequality, New York: Basic Books.

Milanovic, B (2015), “Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of Our Income Is Determined By Where We Live?”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 97(2): 452-460.

Mohammed, A (2015), “Deepening income inequality”, World Economic Forum report.

Pogge, T (2008), World Poverty and Human Rights, Polity Press.

Rawls, J (2001), The Law of Peoples, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J (2000), Equality of Opportunity, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shachar, A (2009), The Birthright Lottery, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Footnote

1 Legal scientists such as Ayalet Shachar have written about addressing global inequality from a legal standpoint, proposing a much more flexible and open definition of citizenship (see Shachar 2009).

Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession

Since 1988, rapid growth in Asia has lifted billions out of poverty. Incomes at the very top of the world income distribution have also grown rapidly, whereas median incomes in rich countries have grown much more slowly. This posting asks whether these developments, while reducing global income inequality overall, might undermine democracy in rich countries.

The period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Great Recession saw probably the most profound reshuffle of individual incomes on the global scale since the Industrial Revolution. This was driven by high growth rates of populous and formerly poor or very poor countries like China, Indonesia, and India; and, on the other hand, by the stagnation or decline of incomes in sub-Saharan Africa and post-communist countries as well as among poorer segments of the population in rich countries.

Anand and Segal (2008) offer a detailed review of the work on global income inequality. In Lakner and Milanovic (2013), we address some of the limitations of these earlier studies and present new results from detailed work on household survey data from about 120 countries over the period 1988–2008. Each country’s distribution is divided into ten deciles (each decile consists of 10% of the national population) according to their per capita disposable income (or consumption). In order to make incomes comparable across countries and time, they are corrected both for domestic inflation and differences in price levels between countries. It is then possible to observe not only how the position of different countries changes over time – as we usually do – but also how the position of various deciles within each country changes. For example, Japan’s top decile remained at the 99th (2nd highest from the top) world percentile, but Japan’s median decile dropped from the 91st to the 88th global percentile. Or, to take another example, the top Chinese urban decile moved from being in the 68th global percentile in 1988 to being in the 83rd global percentile in 2008, thus leapfrogging in the process some 15% of the world population – equivalent to almost a billion people.

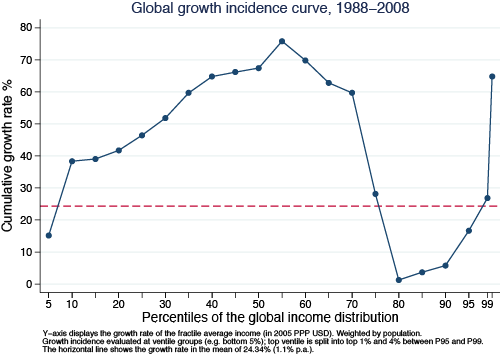

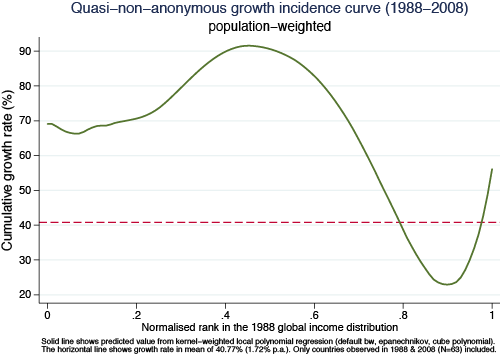

When we line up all individuals in the world, from the poorest to the richest (going from left to right on the horizontal axis in Figure 1), and display on the vertical axis the percentage increase in the real income of the equivalent group over the period 1988–2008, we generate a global growth incidence curve – the first of its kind ever, because such data at the global level were not available before. The curve has an unusual supine S shape, indicating that the largest gains were realised by the groups around the global median (50th percentile) and among the global top 1%. But after the global median, the gains rapidly decrease, becoming almost negligible around the 85th–90th global percentiles and then shooting up for the global top 1%. As a result, growth in the income of the top ventile (top 5%) accounted for 44% of the increase in global income between 1988 and 2008.

Fortunes of income deciles in different countries over time

The curve in Figure 1 is drawn using a simple comparison of real income levels at given percentiles of the global income distribution in 1988 and 2008. It is ‘anonymous’ because it does not tell us what happened to the actual people who were at given global income percentiles in the initial year, 1988. In fact, the regional composition of the different global income groups changed radically over time because growth was uneven across regions. A ‘quasi non-anonymous’ growth incidence curve in Figure 2 adjusts for this – the growth rates are calculated for all individual country/deciles at the positions they held in the initial year (1988). The growth rate on the vertical axis (calculated from a non-parametric fit) thus shows how the country/deciles that were poor, middle-class, rich, etc. in 1988 performed over the next 20 years. The supine S shape still remains, although it is now slightly less dramatic.

People around the median almost doubled their real incomes. Not surprisingly, 9 out of 10 such ‘winners’ were from the ‘resurgent Asia’. For example, a person around the middle of the Chinese urban income distribution saw his or her 1988 real income multiplied by a factor of almost 3; someone in the middle of the Indonesian or Thai income distribution by a factor of 2, Indian by a factor of 1.4, etc.

It is perhaps less expected that people who gained the least were almost entirely from the ‘mature economies’ – OECD members that include also a number of former communist countries. But even when the latter are excluded, the overwhelming majority in that group of ‘losers’ are from the ‘old, conventional’ rich world. But not just anyone from the rich world. Rather, the ‘losers’ were predominantly the people who in their countries belong to the lower halves of national income distributions. Those around the median of the German income distribution have gained only 7% in real terms over 20 years; those in the US, 26%. Those in Japan lost out in real terms.

The particular supine S-shaped growth incidence curve (Figure 1) does not allow us to immediately tell whether global inequality might have gone up or down because the gains around the median (which tend to reduce inequality) may be offset by the gains of the global top 1% (which tend to increase inequality). On balance, however, it turns out that the first element dominates, and that global inequality – as measured by most conventional indicators – went down. The global Gini coefficient fell by almost 2 Gini points (from 72.2 to 70.5) during the past 20 years of globalisation. Was it then all for the better?

Probably yes, but not so simply. The striking association of large gains around the median of the global income distribution – received mostly by the Asian populations – and the stagnation of incomes among the poor or lower middle classes in rich countries, naturally opens the question of whether the two are associated. Does the growth of China and India take place on the back of the middle class in rich countries? There are many studies that, for particular types of workers, discuss the substitutability between rich countries’ low-skilled labour and Asian labour embodied in traded goods and services or outsourcing. Global income data do not allow us to establish or reject the causality. But they are quite suggestive that the two phenomena may be related.

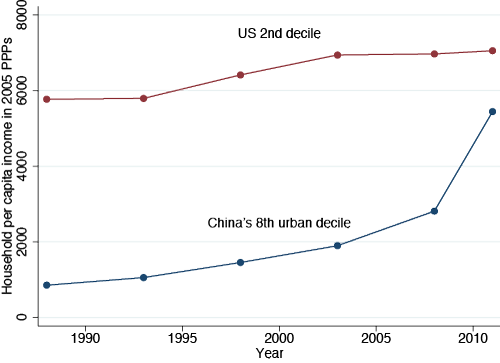

A dramatic way to see the change brought by globalisation is to compare the evolution over time of the 2nd US income decile with (say) the Chinese urban 8th decile (Figure 3). Indeed we are comparing relatively poor people in the US with relatively rich people in China, but given the income differences between the two countries, and that the two groups may be thought to be in some kind of global competition, the comparison makes sense. Here we extend the analysis to 2011, using more recent and preliminary data. While the real income of the US 2nd decile has increased by some 20% in a quarter century, the income of China’s 8th decile has been multiplied by a factor of 6.5. The absolute income gap, still significant five years ago, before the onset of the Great Recession, has narrowed substantially.

Political Implications

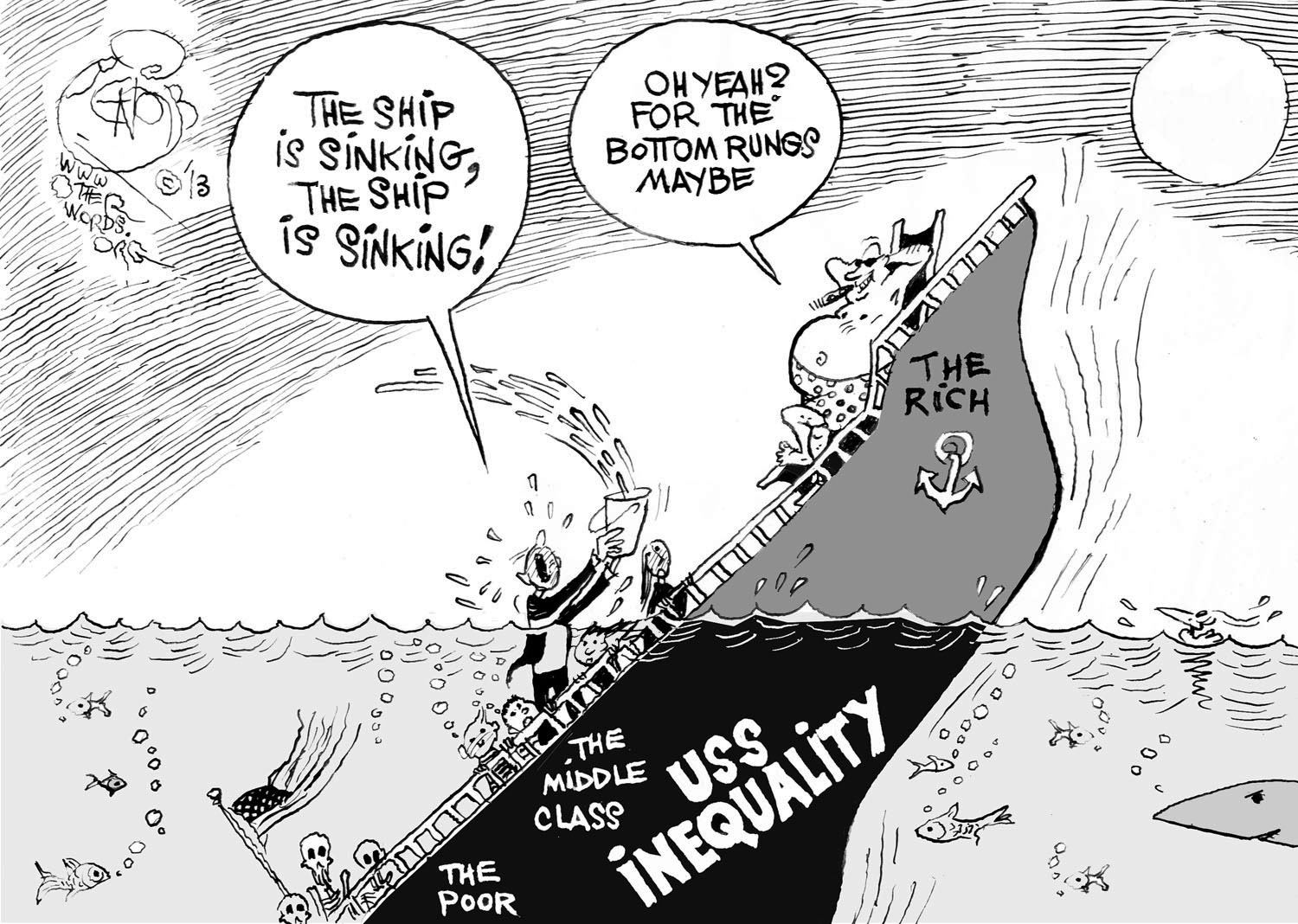

And even if the causality cannot be established because of many technical difficulties and an inability to define credible counterfactuals, the association between the two cannot pass unnoticed. What, then, are its implications? First, will the bottom incomes of the rich countries continue to stagnate as the rest of China, or later Indonesia, Nigeria, India, etc. follow the upward movement of Chinese workers through the ranks of the global income distribution? Does this imply that the developments that are indeed profoundly positive from the global point of view may prove to be destabilising for individual rich countries?

Second, if we take a simplistic, but effective, view that democracy is correlated with a large and vibrant middle class, its continued hollowing-out in the rich world would, combined with growth of incomes at the top, imply a movement away from democracy and towards forms of plutocracy. Could then the developing countries, with their rising middle classes, become more democratic and the US, with its shrinking middle class, less?

Third, and probably the most difficult: What would such movements, if they continue for a couple of decades, imply for global stability? The formation of a global middle class, or the already perceptible ‘homogenisation’ of the global top 1%, regardless of their nationality, may be both deemed good for world stability and interdependency, and socially bad for individual countries as the rich get ‘delinked’ from their fellow citizens.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, the movements that we witness do not only lead to an economic rebalancing of the East and West – in which both may end up with global output shares close to what they had before the Industrial Revolution – but to a contradiction between the current world order, where political power is concentrated at the level of the nation-state, and the economic forces of globalization which have gone far beyond it.

References

Anand, Sudhir and Paul Segal (2008), “What Do We Know about Global Income Inequality?”, Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1): 57–94.

Lakner, Christoph and Branko Milanovic (2013), “Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession”, World Bank Working Paper No. 6719, December.

Redistribution, Inequality, and Sustainable Growth: Reconsidering the Evidence

Inequality has the potential to undermine growth. However, greater redistribution requires higher tax rates, which reduce incentives to work and save. Moreover, the evidence that inequality is bad for growth might simply reflect the fact that more unequal societies choose to redistribute more, and those efforts are antithetical to growth. This column presents evidence from a new dataset on pre- and post-tax inequality. The authors find that income equality is protective of growth, and that redistributive transfers on average have little if any direct adverse impact on growth.

Rising income inequality looms high on the global policy agenda, reflecting not only fears of its pernicious social and political effects (including questions about the consistency of extreme inequality with democratic governance), but also its economic implications. While positive incentives are surely needed to reward work and innovation, excessive inequality is likely to undercut growth – for example by undermining access to health and education, causing investment-reducing political and economic instability, and thwarting the social consensus required to adjust in the face of major shocks.

Understandably, economists have been trying to understand better the links between rising inequality and the fragility of economic growth. Recent narratives include how inequality intensified the leverage and financial cycle, sowing the seeds of crisis (Rajan 2010), or how political-economy factors – especially the influence of the rich – allowed financial excess to balloon ahead of the crisis (Stiglitz 2012).

But what is the role of policy – and in particular fiscal redistribution – in bringing about greater equality? Conventional wisdom suggests that redistribution would in itself be bad for growth, but by reducing inequality, it might conceivably help growth. Looking at past experience, we find scant evidence that typical efforts to redistribute have on average had an adverse effect on growth. Moreover, faster and more durable growth seems to have followed the associated reduction in inequality.

Disentangling the Effects of Inequality and Redistribution on Growth

In earlier work (Berg and Ostry 2011), we documented a robust medium-run relationship between equality and the sustainability of growth. We did not, however, have much to say on whether this relationship justifies efforts to redistribute.

Indeed, many argue that redistribution undermines growth, and even that efforts to redistribute to address high inequality are the source of the correlation between inequality and low growth. If this is right, then taxes and transfers may be precisely the wrong remedy – a cure that may be worse than the disease itself.

The literature on this score remains controversial. A number of papers (e.g. Benabou 2000) point out that some policies that are redistributive – e.g. public investments in infrastructure, spending on health and education, and social insurance provision – may be both pro-growth and pro-equality. Others are more supportive of a fundamental tradeoff between redistribution and growth, as argued by Okun (1975) when he referred to the efficiency ‘leaks’ that come with efforts to reduce inequality.

In a new paper (Ostry et al. 2014), we ask what the historical data say about the relationship between inequality, redistribution, and growth. In particular, what is the evidence about the macroeconomic effects of redistributive policies – both directly on growth, and indirectly as they reduce inequality, which in turn affects growth?

To disentangle the channels, we make use of a new cross-country dataset that carefully distinguishes net (post-tax and transfers) inequality from market (pre-tax and transfers) inequality, and allows us to calculate redistributive transfers for a large number of countries over time – covering both advanced and developing countries. We analyse the behaviour of average growth during five-year periods, as well as the sustainability and duration of growth.

Our key questions are empirical. How big is the ‘big tradeoff’? How does the direct (in Okun’s view negative) effect of redistribution compare to its indirect and apparently positive effect through reduced inequality?

Some Striking Results on the Links between Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth

- First, we continue to find that inequality is a robust and powerful determinant both of the pace of medium-term growth and of the duration of growth spells, even controlling for the size of redistributive transfers.

Thus, it would still be a mistake to focus on growth and let inequality take care of itself, if only because the resulting growth may be low and unsustainable. Inequality and unsustainable growth may be two sides of the same coin.

- Second, there is remarkably little evidence in the historical data used in our paper of adverse effects of fiscal redistribution on growth.

The average redistribution, and the associated reduction in inequality, seem to be robustly associated with higher and more durable growth. We find some mixed signs that very large redistributions may have direct negative effects on growth duration, such that the overall effect – including the positive effect on growth through lower inequality – is roughly growth-neutral.

Caveats

These findings may suggest that countries that have carried out redistributive policies have actually designed those policies in a reasonably efficient way. However, it does not mean of course that countries wishing to enhance the redistributive role of fiscal policy should not pay attention to efficiency considerations. This is especially important for countries with weak governance and administrative capacity, where developing tax and spending instruments that can allow governments to undertake redistribution efficiently are of the essence. A forthcoming paper by the IMF will delve into these fiscal issues.

Of course, we should also be cautious about drawing definitive policy implications from cross-country regression analysis alone. We know from history and first principles that after some point redistribution will be destructive to growth, and that beyond some point extreme equality also cannot be conducive to growth. Causality is difficult to establish with full confidence, and we also know that different sorts of policies are likely to have different effects in different countries at different times.

Bottom line

The conclusion that emerges from the historical macroeconomic data used in this paper is that, on average across countries and over time, the things that governments have typically done to redistribute do not seem to have led to bad growth outcomes. Quite apart from ethical, political, or broader social considerations, the resulting equality seems to have helped support faster and more durable growth.

To put it simply, we find little evidence of a ‘big tradeoff’ between redistribution and growth. Inaction in the face of high inequality thus seems unlikely to be warranted in many cases.

References

Benabou, R (2000), “Unequal Societies: Income Distribution and the Social Contract”, The American Economic Review, 90(1): 96–129.

Berg, A, J D Ostry, and J Zettelmeyer (2012), “What Makes Growth Sustained?”, Journal of Development Economics, 98(2): 149–166.

Berg, A and J D Ostry (2011), “Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?”, IMF Staff Discussion Note 11/08.

Okun, A M (1975), Equality and Efficiency: the Big Trade-Off, Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Ostry, J D, A Berg, and C G Tsangarides (2014), “Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth”, IMF Staff Discussion Note 14/02.

Rajan, R (2010), Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stiglitz, J (2012), The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, W W Norton & Company.

Can Democracy Help with Inequality?

Inequality is currently a prominent topic of debate in Western democracies. In democratic countries, we might expect rising inequality to be partially offset by an increase in political support for redistribution. This column argues that the relationship between democracy, redistribution, and inequality is more complicated than that. Elites in newly democratized countries may hold on to power in other ways, the liberalization of occupational choice may increase inequality among previously excluded groups, and the middle classes may redistribute income away from the poor as well as the rich.

There is a great deal of concern at the moment about the consequences of rising levels of inequality in North America and Western Europe. Will this lead to an oligarchisation of the political system, and imperil political and social stability? Many find such dynamics puzzling given that it is happening in democratic countries. In democratic societies, there ought to be political mechanisms that can inhibit or reverse large rises in inequality, most likely through the fiscal system. Indeed, one of the most central models in political economy, due originally to Meltzer and Richard (1981), suggests that high inequality in a democracy should lead the politically powerful (in their model the voter at the median of the income distribution) to vote for higher levels of taxes and redistribution, which would partially offset rising inequality.

But before asking about what happens in a democracy, we could start with some even more fundamental questions. Is it correct factually that democracies redistribute more income than dictatorships? When a country becomes democratic, does this tend to increase redistribution and reduce inequality? The existing scholarship on these questions, though vast, is quite contradictory. Historical studies, such as Acemoglu and Robinson (2000) and Lindert (2004), tend to suggest that democratization increases redistribution and reduces inequality. Using cross-national data, Gil et al. (2004) find no correlation between democracy as measured by the Polity score and any government spending or policy outcome. The evidence on the impact of democracy on inequality is similarly puzzling. An early survey by Sirowy and Inkeles (1990) concludes, “the existing evidence suggests that the level of political democracy as measured at one point in time tends not to be widely associated with lower levels of income inequality” (p. 151), though Rodrik (1999) finds that both the Freedom House and Polity III measures of democracy were positively correlated with average real wages in manufacturing and the share of wages in national income (in specifications that also control for productivity, GDP per capita, and a price index).

In a recent working paper (Acemoglu et al. 2013), we revisit these questions both theoretically and empirically.

Theoretical Nuances

Theoretically, we point out why the relationship between democracy, redistribution, and inequality may be more complex than the discussion above might suggest. First, democracy may be ‘captured’ or ‘constrained’. In particular, even though democracy clearly changes the distribution of de jure power in society, policy outcomes and inequality depend not just on the de jure but also the de facto distribution of power. Acemoglu and Robinson (2008) argue that, under certain circumstances, elites who see their de jure power eroded by democratization may sufficiently increase their investments in de facto power (e.g. via control of local law enforcement, mobilization of non-state armed actors, lobbying, and other means of capturing the party system) in order to continue to control the political process. If so, we would not see much impact of democratization on redistribution and inequality. Similarly, democracy may be constrained by other de jure institutions such as constitutions, conservative political parties, and judiciaries, or by de facto threats of coups, capital flight, or widespread tax evasion by the elite.

Democratization can also result in ‘inequality-increasing market opportunities’. Non-democracy may exclude a large fraction of the population from productive occupations (e.g. skilled occupations) and entrepreneurship (including lucrative contracts), as in Apartheid South Africa or the former Soviet Union. To the extent that there is significant heterogeneity within this population, the freedom to take part in economic activities on a more level playing field with the previous elite may actually increase inequality within the excluded or repressed group, and consequently the entire society.