Archive

Capitalist Systems and Income Inequality

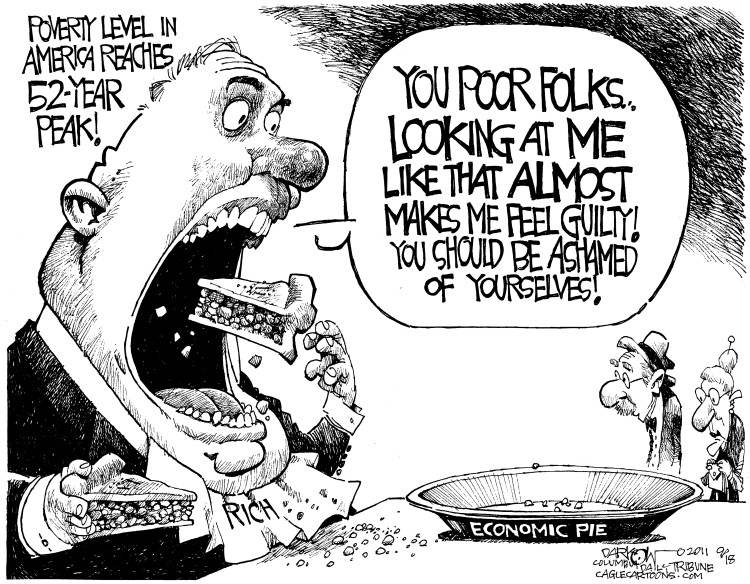

Similar levels of income inequality may coexist with completely different distributions of capital and labor incomes. This column introduces a new measure of compositional inequality, allowing the authors to distinguish between different capitalist societies. The analysis suggests that Latin America and India are rigid ‘class-based’ societies, whereas in most of Western European and North American economies (as well as in Japan and China), the split between capitalists and workers is less sharp and inequality is moderate or low. Nordic countries are ‘class-based’ yet fairly equal. Taiwan and Slovakia are closest to classless and low inequality societies.

Similar levels of income inequality may be characterised by completely different distributions of capital and labour. People who belonged to the highest income decile in the US before WWII received mainly capital incomes, whereas in 2010 people in the highest decile earned both high labour and capital incomes (Piketty 2014). Yet the difference in their total income shares was small.

Different distributions of capital and labour describe different economic systems. Two polar systems are particularly relevant. In classical capitalism – explicit in the writings of Ricardo (1994 [1817]) and Marx (1992 [1867], 1993 [1885]) ¬– a group of people receives incomes entirely from ownership of assets while another group’s income derives entirely from labour. The first group (capitalists) is generally small and rich; the latter (workers) is generally numerous and poor, or at best with middling income levels. The system is characterised by high income inequality.

In today’s liberal capitalism, however, a significant percentage of people receive incomes from both capital and labour (Milanovic 2019). It is still true that the share of one’s income derived from capital increases as we move higher in the income distribution, but very often the rich have both high capital and high labour incomes. While inter-personal income inequality may still be high, inequality in composition of income is much less.

The purpose of our study is to introduce a new way of looking at inequality that allows us to classify empirically different forms of capitalism. In addition to the usual inter-personal income inequality, we look at inequality in the factoral (capital or labour) composition of people’s incomes. The class analysis (where class is defined narrowly depending on the type of income one receives) is thus separated from the analysis of income inequality proper.

Which countries around the world are closer to classical, and which to liberal capitalism? Does classical capitalism display higher inter-personal income inequality than liberal capitalism? Can we find what we term ‘homoploutic’ societies – where everyone has approximately the same shares of capital and labour income? Would such homoploutic societies display high or low levels of income inequality?

To answer these questions, in Ranaldi and Milanovic (2020) we adopt a new statistic, recently developed by Ranaldi (2020), to estimate compositional inequality of incomes: the income-factor concentration (IFC) index. The income-factor concentration index is at the maximum when individuals at the top and at the bottom of the total income distribution earn two different types of income, and minimal when each individual has the same shares of capital and labour income. When the income-factor concentration index is close to one (maximal value), compositional inequality is high, and a society can be associated to classical capitalism. When the index is close to zero, compositional inequality is low and a society can be seen as homoploutic capitalism. Liberal capitalism would lie in-between. Negative values of the income-factor concentration index, which describe societies with poor capitalists and rich workers, are unlikely to be found in practice.

By applying this methodology to 47 countries with micro data provided by Luxembourg Income Study from Europe, North America, Oceania, Asia, and Latin America in the last 25 years and covering approximately the 80% of world output, three main empirical findings emerge.

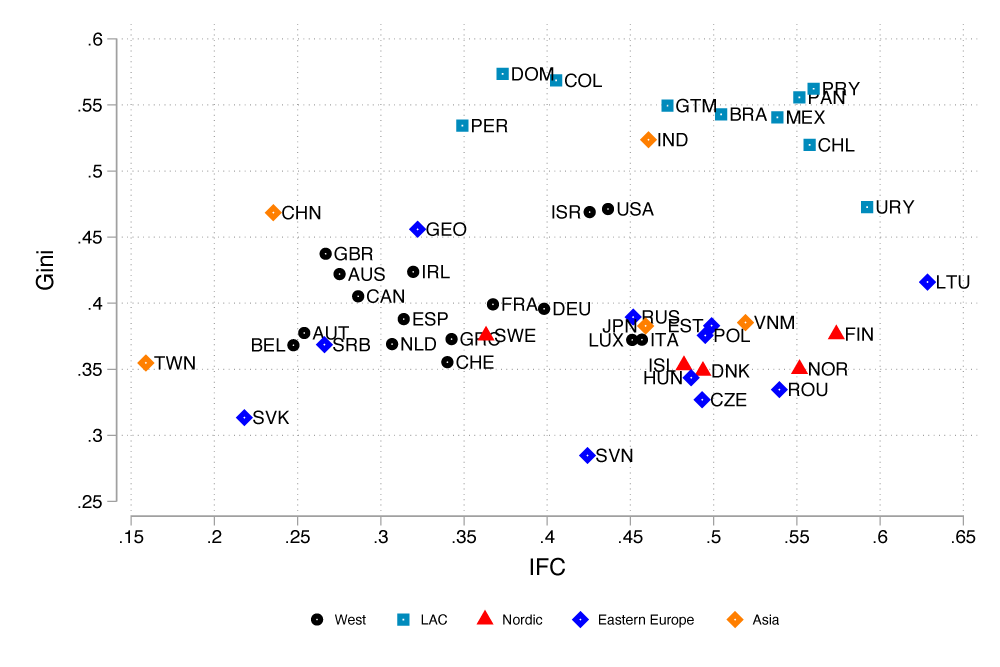

First, classical capitalism tends to be associated with higher income inequality than liberal capitalism (see Figure 1). Although this relationship was implicit in the minds of classical authors like Ricardo and Marx, as well as in recent studies of pre-WWI inequality in countries that are thought to have had strong class divisions (Bartels et al. 2020, Gómes Léon and de Jong 2018), it was never tested empirically.

Second, three major clusters emerge at the global scale. The first cluster is the one of advanced economies, which includes Western Europe, North America, and Oceania. Relatively low to moderate levels of both income and compositional inequality characterize this cluster. The US and Israel stand somewhat apart from the core countries since they display higher inequality in both dimensions.

Latin American countries represent the second cluster, and are, on average, characterised by high levels in both inequality dimensions.

The third cluster is composed of Nordic countries and is exceptional insofar as it combines low levels of income inequality with high compositional inequality. This is not entirely surprising: Nordic countries are known to combine wage compressions with ‘socially acceptable’ high returns to capital (Moene and Wallerstein 2003, Moene 2016). Such compromise between capital and labour (reached in the early 1930s) has put a cap on earning inequality within the region (Fochesato and Bowles 2015) but has left wealth inequality untouched (Davies et al. 2012). By drastically reducing the progressivity of capital income taxation (Iacono and Palagi 2020), income tax reforms during the 1990s have worked in the same direction.

Several other results are found. Many Eastern European countries are close to the Nordic cluster. Some (Lithuania and Romania) have very high compositional inequality, likely the product of concentrated privatisation of state assets. India is very similar to the Latin American cluster, displaying a class-based structure with high levels of income inequality.

Taiwan and Slovakia are, instead, the most ‘classless’ societies of all. They combine very low levels of income and compositional inequality. This makes them ‘inequality-resistant’ to the increase in the capital share of income. In other words, if capital share continues to rise due to further automation and robotics (Baldwin 2019, Marin 2014), it will not push inter-personal inequality up: everybody’s income would increase by the same percentage. The link between the functional and personal income distribution in such societies is weak – the topic of a previous VoxEU column by Milanovic (2017b). It is also interesting that Taiwan is both more ‘classless’ and less unequal than China.

The third, and perhaps most striking result that emerges from our analysis is that no one country in our sample occupies the north-west part of the diagram. We find no evidence of countries combining low levels of compositional inequality (like those of Taiwan and Slovakia) with extremely high levels of income inequality (like in Latin America).

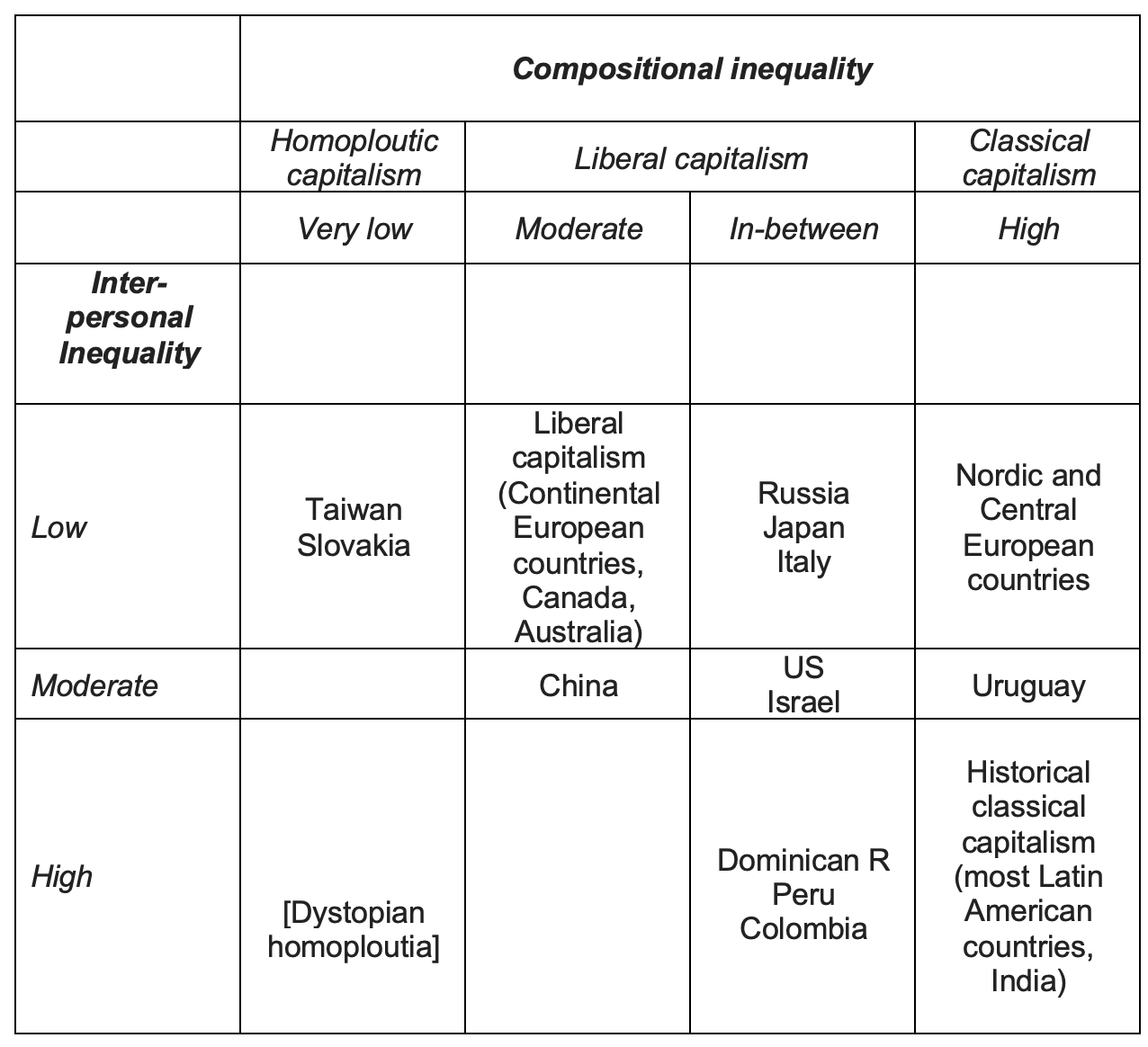

To conclude, we propose a novel taxonomy of varieties of capitalism on the basis of the two inequality dimensions (Table 1). We believe such taxonomy brings a strong empirical and distributional focus into the literature on the varieties of capitalism, as well as a larger geographical coverage.

References

Baldwin, R (2019), The Globotics Upheaval: Globalization, Robotics and the Future of Work, Princeton University Press.

Bartels, C, F Kersting and N Wolf (2020), “Testing Marx: Inequality, Concentration and Political Polarization in late 19th Century Germany”, German Institute for Economic Research.

Davies, J, R Lluberas and A Shorrocks (2012), Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report 2012.

Fochesato, M and S Bowles (2015), “Nordic exceptionalism? Social democratic egalitarianism in world-historic perspective”, Journal of Public Economics 127: 30-44.

Gómes Léon, M and H J de Jong (2018), “Inequality in turbulent times: income distribution in Germany and Britain, 1900–50”, Economic History Review.

Iacono, R and E Palagi (2020), “Still the Lands of Equality? On the Heterogeneity of Individual Factor Income Shares in the Nordics”, LIS working papers series 791.

Marin, D (2014), “Globalization and the Rise of the Robots”, Vox.EU.org, 15 November.

Marx, K (1992 [1867]), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy 1, translated by B Fowkes, London: Penguin Classics.

Marx, K (1993 [1885]), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy 3, translated by D Fernbach, London: Penguin Classics.

Milanovic, B (2017a), “Increasing Capital Income Share and its Effect on Personal Income Inequality”, in H Boushey, J Bradford DeLong and M Steinbaum (eds) After Piketty. The Agenda for Economics and Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Milanovic, B (2017b), “Rising Capital Share and Transmission Into Higher Interpersonal Inequality”, Vox.EU.org, 16 May.

Milanovic, B (2019), Capitalism, Alone, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Moene, K O and M Wallerstein (2003), “Social democracy as a development strategy”, Department of Economics, University of Oslo 35/2003.

Moene, K O (2016), “The Social Upper Class under Social Democracy”, Nordic Economic Policy Review 2: 245–261.

Ricardo, D (2004 [1817]), The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, London: Dover publications.

Ranaldi, M (2020), “Income Composition Inequality”, Stone Center Working Paper Series 7.

Ranaldi, M and B Milanovic (2020), “Capitalist Systems and Income Inequality”, Stone Center Working Paper Series 25.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, translate by A Goldhammer, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

How Financial Inclusion is Driving Fairer Growth in Emerging Markets?

Rising global inequality is one of the biggest social and economic challenges of the 21st Century—a problem further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. While inequality is a global issue, it is often more pointedly felt in emerging countries, as they tend to have a large informal sector, greater regional divides, wider gaps in access to education, and more significant barriers to employment for women. Financial inclusion is often seen as an important factor in bridging these divides, while also supporting better economic and social outcomes.

This article discusses how financial inclusion supports fairer development in emerging countries, highlights some leading examples, and outlines how the investment landscape may evolve over time. Financial inclusion is becoming a key priority for governments, and will therefore likely increasingly matter to businesses and investors. The integration of finance with technology is helping accelerate financial inclusion, creating compelling investment opportunities within fast-growing economies.

Financial Inclusion at a Glance

Financial inclusion is the process of providing suitable financial services to the “unbanked” (individuals or businesses) in an affordable, sustainable, and ethical way. This can involve access to traditional credit through banking and insurance products, but also saving mechanisms for healthcare or education and even investment products, allowing citizens to benefit further from the rapid growth of their economies.

It has been shown that increasing financial inclusion can drive economic development, possibly increase GDP by up to 14% in EM and a staggering 30%1 in frontier economies. According to World Bank studies, globally around 1.7 billion people, or 31% of the adult population, lack access to financial services.2 Half of this unbanked population live in Asia, 25% in Africa, and 10% in Latin America. A significant portion of these unbanked groups are women. Therefore, improved financial inclusion can also lead to greater gender equality.

Financial inclusion is a key enabler of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which will be a key driver of reducing poverty and enhancing shared global economic prosperity. This is important to investors as economic growth is a fundamental long-term driver of corporate revenues and earnings, which supports asset prices. Financial inclusion’s importance is illustrated by being a target in no less than seven of the 17 goals (Exhibit 1).

For example, through better access to financial services such as bank accounts and insurance products, citizens in emerging countries can come out of poverty (enabling SDG 1). Access to funds and insurance also helps people working agriculture to better manage their finances, achieve higher yields, and thereby increase food security (SDG 2 and SDG 3). Financial inclusion means people can invest in their children’s education (SDG 4) and improved female empowerment can address gender equality (SDG 5). These five SDGs feed into the wider socio-economic goals such as shared economic growth (SDG 8) and innovation and sustainable industrialisation (SDG 9).

Regulators are also prioritizing financial inclusion, given the link to economic growth. Over 60 countries have made commitments to financial inclusion, and more than 50 have launched or developed a national financial inclusion strategy. digitization and electronic transactions have helped fuel an increase in financial inclusion rates. Some of the leading examples of rapid financial inclusion have been within India and Kenya, where access to accounts has grown rapidly in last decade (Exhibit 2). However, there still remains a wide disparity between countries (Exhibit 3).

How Tech and Digitization Is Driving Financial Inclusion

The growing importance of financial inclusion provides a structural opportunity for financial institutions and businesses, with some already capitalising on this shift. Small and mid-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a central role in financial inclusion as they represent about 90% of business and more than 50% of employment worldwide.3 Formal SMEs, which tend to be more structured businesses with contracted employees, salaries and other employment benefits, contribute up to 40% of GDP in EM, and this figure is even larger when more informal businesses are included. However, nearly half of the SMEs in developing countries face challenges in obtaining finance, representing a $5.2 trillion unmet annual financing need.4 This compares to a favourable 15% of SMEs in high-income countries. The low EM penetration rate highlights how providing financial services to segments that lack financing can be a huge structural growth opportunity for businesses.

Traditional banking rarely allows money to reach lower market segments (such as micro credit and SME) for cost and/or efficiency reasons, necessitating the need for new business models. The rapid evolution of fintech, digital, and mobile banking is accelerating the rate of financial inclusion by raising efficiency, lowering transaction costs, and expanding outreach to new clients and markets. This digital evolution, which has sharply increased during the pandemic, is disrupting high cost of customer acquisition/interactions, credit assessment, and credit underwriting. It is also enhancing cross selling of products and accelerating growth.

Leading Country Case Studies

India – Powerful Public and Private Partnerships

One of the fastest-growing markets for financial inclusion is India, driven by government initiatives as well as public-private partnerships. Examples include the PM Jan Dhan Yojana scheme (PMJDY), priority sector lending directives to all financial institutions, as well as the government’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) platform.

Under the JD scheme, Indians were given the facility to open a Jan Dhan bank account using the Adhar biometric ID system. This, together with a fast-growing mobile usage, has accelerated digital adoption. As a result, 424 million Indian citizens have been served by PMJDY as of May 2021, including 234 million female customers. The scheme has also increased the number of banking outlets in rural Indian villages from 67,694 in March 2010 to nearly 13 million by the end of 2020.5 The establishment of the UPI, an instant real-time payment system, has also increased usage of cashless payments, with major telecom players helping drive adoption.

Kenya – Pioneering Mobile Banking Success

Kenya stands out as a success story for financial inclusion due to its early adoption of mobile banking and the fintech revolution. This has led to a very high percentage of the population having access to a bank account relative to peer countries. Much of this achievement is due to the mobile banking M-Pesa system, started by Safaricom and Vodafone. Leveraging the network of telecom subscribers, it allows mobile payments, and provides banking access to the rural population where bank branches would be too expensive to operate.

Mobile money transactions are now well established in Kenya, accounting for a staggering 44% of GDP in 2019.6 Financial institutions such as Equity Bank have successfully used the mobile and agency banking model to expand access to banking services much more quickly and efficiently than through traditional banks. The socioeconomic impact of mobile banking has been significant in Kenya. It is estimated that M-Pesa alone has lifted 2% of the Kenyan household out of poverty.7

China – Accelerating Digital Payments and E-commerce

The SARS epidemic in 2003 changed consumer behaviour towards e-commerce and accelerated the launch of e-commerce and digital payments in China. Alibaba launched Taobao that year, its first e-commerce website, and soon after created Alipay to help online payments acceleration. JD.com also started selling products online in 2003.8 This shift, supported by a robust identification system and internet infrastructure, has resulted in lasting online payments adoption, with China now the leader in digital wallets and digital payments. The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated the rise in digital payments transactions in China and globally. This trend will likely be supported further by the adoption of digital currencies.

Brazil – Frontline in Fintech Innovation

Brazil is becoming a hub for fintech and digital innovation which should accelerate financial inclusion, especially as the fintech disrupters are focusing on mass market and SME lending targeting the approximately 55 million of Brazil’s 213 million population which remains unbanked. Although Brazil has one of the highest numbers of fintech start-ups, the companies with payment offerings as well as credit track record tools are fast becoming the more successful financial inclusion businesses. Some traditional banking groups are also embracing digitisation, helping to drive further financial inclusion. Liberal banking regulations and the launch of PIX, an instant payment platform offered by the Central Bank of Brazil, have also increased digital adoption. This should make the market more competitive and services more affordable for customers.

Mexico – Bridging the Gender Finance Gap

Mexico has some of the lowest financial penetration rates in GDP per capita and HDI (Human Development Index) terms, especially with respect to women. At its level of development, financial inclusion for women should be much higher than the current 33% level.9

One company really driving financial inclusion in Mexico is Gentera, which is the country’s largest microfinance institution (MFI), serving clients at the bottom of the socioeconomic pyramid. Focusing on group lending for women through its Crédito Mujer service, the company has built a client base which is 89% female and accounts for 16% of all female borrowing in Mexico. A key driver of its success has been the group-lending model and ability to maintain low default rates, despite income variability and the lack of credit history, using group/community guarantees. Gentera also contributed to social impact during the challenges created by COVID-19 by providing services to clients while simultaneously suspending interest payments.

How We See the Investment Landscape Evolving

Financial inclusion is not just a sustainability trend, it is also structural growth opportunity for businesses and investors. Traditional financial inclusion models have largely focused on micro-lending of cash loans to either support working capital needs or bridge consumption needs. However, limited micro credit models are increasingly being challenged.

A significant amount of evidence suggests that low income households need access to much wider range of financial services to generate income, build assets, smooth consumption, and manage risks. These include products such as savings, insurance and healthcare, transfer payments, and pension etc, not just access to credit. The businesses carving out large market presences in these areas, while adopting digitisation, are likely to enjoy higher growth, and for longer, as developing economies benefit from global technological advances.

We believe fintech has begun to take over where traditional banks have not managed to service significant segments of the population or SMEs, and this is where we are seeing exciting opportunities. Financial inclusion opportunities are greatest in markets that embrace and support technological innovations and effectively regulate the segment, as illustrated in in Kenya, Brazil, and India.

Overall, we see financial inclusion being a key priority for the UN SDGs and governments, which in turn should drive business agenda and investor interest. With COVID-19 exposing and worsening social inequalities between nations and within societies, the importance of supporting financial inclusion has never been more of a priority for building a stronger and more inclusive global economy.

Notes

1 Source: EY (2018). Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/en_cz/news/2018/01/improved-financial-inclusion-could-boost-global-bank-revenues-by-us-200b

2 Source: World Bank (2017). Retrieved from https://globalfindex.worldbank.org/sites/globalfindex/files/chapters/2017%20Findex%20full%20report_chapter2.pdf

3 Source: UN (2020). Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/observances/micro-small-medium-businesses-day

4 Source: World Bank. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance

5 Source: Reserve Bank of India (2020)

6 Source: Central Bank of Kenya (2019)

7 Source: MIT News (2016). Retrieved from https://news.mit.edu/2016/mobile-money-kenyans-out-poverty-1208

8 Source: World Economic Forum (2020). Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/digital-payments-cash-and-covid-19-pandemics

9 Source: GIWPS (2019). Retrieved from https://giwps.georgetown.edu/index-story/mexico/

A Sudden Topicality

Karl Marx was a thinker of crisis. But in what sense was he a theorist of crisis? In what sense did he propound something that might legitimately be called a ‘crisis theory’?*The question may seem an odd one. After all, although there is no one text by Marx specifically dedicated to the topic, it is generally held to be pervasive throughout his economic and political writings from the late 1840s onwards; indeed, to constitute their very rationale – the energizing demonstration of the necessity of social change, via the demonstration of the tendency to crisis inherent in the capitalist mode of production itself. Marxists have long debated the meaning and significance of the ‘crisis theory’ contained in Marx’s passages on this topic – in particular, the question of whether or not it constitutes a theory of breakdown or collapse (Zusammenbruch). This question was at the heart of the revisionist controversies around the time of the First War World, for example, in which both Rosa Luxemburg (The Accumulation of Capital, 1913) and, later, Henryk Grossman (The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System, 1929) upheld the theory of breakdown against what were held to be ‘revisionist’ positions.

The revival of Marxist theory in Western Europe in the 1960s and 1970s brought a corresponding revival of interest in crisis theory. Numerous new books and articles were published on the topic, with titles like (from the anglophone literature) ‘The Marxian Theory of Crises, Capital and the State’ (David Yaffe, 1972), Capitalism and Crisis (Walton and Gamble, 1976), United States Capitalism in Crisis (Union of Radical Political Economists, 1978) and Economic Crisis and Crisis Theory (Paul Mattick, 1981), leading up to Simon Clarke’s synthetic Marx’s Theory of Crisis (1993).1 In the last two years the genre has been revived once again. In the UK, the 2007 Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize (the only significant English-language book prize for a work of historical materialism) went to Rick Kuhn’s Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism. The most recent book by the 2004 winner of the prize, Michael Lebowitz, returns to his work on crisis theory from over twenty years ago. And the journal at the centre of the revival of Marxist Studies in the anglophone academy, Historical Materialism (founded in 1992), has carried various articles and a symposium theorizing the current global financial crisis in terms of Marx’s theory of crisis. [2] To each crisis, we might say, its own revival of Marx’s ‘theory of crisis’.

This alone should give us pause for thought. (I still recall the manner in which, at the Socialist Movement conference in Chesterfield in the north of England on Monday 19 October 1987, the day of what is still the largest one-day stock market crash in history – the Dow dropped over 22 per cent, in a crash unconnected to a general crisis – by the early afternoon, the Trotskyist economists associated with the then recently abolished Greater London Council publicly announced the arrival of the long-awaited collapse of the capitalist system.) Just as Marx saw periodic crises as ‘bringing to the surface’ the underlying ‘barrier’ (Schranke) to the development of the productive forces inherent within the capitalist mode of production, [3] so economic crises also bring to the surface a desire to displace the politics of social transformation onto economic events. In this respect, one might say: periodic economic crises are windows onto the permanent crisis of Marxist political thought.

In counter-position to this recurring dependence of a politics of fundamental social transformation upon periodic economic crises, Antonio Negri has argued that the problem with the Marxian analytic of subsumed labour is that it ‘exclude[s] social labour* This is the text of a talk to ‘Los Pensadores de la Crisis Contemporanea: Marx, Weber, Keynes, Schmit ’, Universidad Internacional Menéndez Pelayo, Valencia, 2–4 December 2009, organized by José Luis Vil acañas Berlanga, Alberto Moreiras and Étienne Balibar.power as the potentiality for crisis’, neglecting ‘the antagonism that the plural substantial times of subjects oppose to the analytic of command’. [4] Negri thereby posits the possibility of a purely political kind of capitalist crisis. Yet such a purely political antagonism has shown no signs of generating a crisis for the capitalist order. (The ontologization of politics appears here as a symptom of the crisis of political thought, rather than its solution.) Negri’s accompanying declaration that, ‘synonymous with real subsumption’, crisis is now ‘simultaneous and stable’, indeed ‘consubstantial with the current phase of capitalist development’, redefines out of existence the politically crucial aspect of the traditional idea of crisis: namely, the conception of crisis as a decisive turning point in a process, a point at which a decision must be made. (But by whom or what?) Marx himself famously insisted, against Adam Smith: ‘Permanent crises do not exist.’ [5] It is the tendency towards and potentiality for crisis that is permanent, not the crisis itself.

Crises of Accumulation, Crisis of Capitalism?

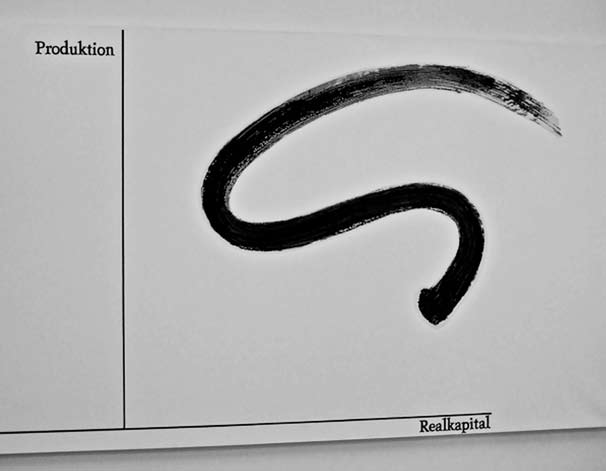

The doubt as to whether Marx should be thought of a crisis theorist – as opposed to a ‘thinker’ of crisis in some more general, yet-to-be-determined sense – stems from the disjunction between the all pervasive, general-historical character of the concept of crisis in its modern form (including the historicopolitical notion of a crisis of the capitalist system as a whole, as a condition of a transition to a new mode of production – a notion which clearly motivated Marx), on the one hand, and the restrictedly conjunctural character and relatively narrow political-economic basis of Marx’s so-called ‘theory of crisis’, as a theory of periodic crises or cycles within capitalism, on the other. For Marx, economic crises within capitalism are normal stages in the conjunctural cycle or spiral of expanded reproduction. Textually, what is thought of as the theory of such crises is primarily to be found in Part 3 of Volume 3 of Capital – put together by Engels from Marx’s notes and published in 1894 as ‘The Law of the Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall’ (especially chapter 15, ‘Exposition of the Internal Contradictions of the Law’) – along with some passages in the Grundrisse (in ‘The Chapter on Capital’) and Theories of Surplus Value (especially chapter 17), which describe ‘overproduction’ as ‘the fundamental contradiction of developed capital’ and ‘the basic phenomenon in crises’, respectively. [6] In so far as there is a general theory of capitalist crisis here, it is threefold. 1. Crises are modes of appearance of structural contradictions within the process of capitalist production – they bring contradictions ‘to the surface’, as Marx says. 2. Crises are means for the temporary solution, and hence new forms of mediation, of such contradictions, which restore the conditions for accumulation. 3. The restoration of conditions for accumulation is at the same time the renewal of the terms of the contradictions within the system that gave rise to the crisis in the first place.

Hence the ‘periodic’ or ‘cyclical’ character of such crises, taking the developmental form of a spiral. As Marx put it in Capital:From time to time [periodisch] the conflict of antagonistic agencies finds vent in crises. The crises are always but momentary and forcible solutions of the existing contradictions. They are violent eruptions that for a time [den Augenblick] restore the disturbed equilibrium. [7] The mechanism of the capitalist production process itself removes the very obstacles it temporarily creates. [8] Capitalist production seeks continual y to overcome these immanent barriers, but overcomes them only by means which again place these barriers in its way and on a more formidable scale. [9]

Debate has focused on whether crisis tendencies can always, in principle, be countered by what Marx called ‘counteracting tendencies’ (widerstrebende Tendenzen) [10] and, we must add, crucially, their political management (the Keynesian moment – a crucial aspect of the process that is no longer part of ‘the capitalist production process itself’) or whether the barriers to the development of productive forces that are involved represent some kind of cumulative ultimate limit to capital accumulation, since, in Marx’s famous words in Chapter 15 of Capital, Volume 3: ‘The true barrier [Die wahre Schranke] to capitalist production is capital itself.’ [11] As David Harvey has recently pointed out: ‘How to understand crisis formation remains … by far the most contentious issue in Marxian political economy.’ [12] There are a number of theoretical difficulties here.

First, Marx’s recurring discussions of the ‘immanent barriers’ to capital accumulation determine limits purely formally, in comparison with hypothetically ‘unfettered’ production at the same level of development of the productive forces. There is no sense that a subsequent mode of production might impose its own, different kind of limits to production. ‘Limit’ here is thus the negative or reverse side of a productivist utopianism (to be distinguished from its use by Marx in the sense of those ‘limits of variation’ that define the field of operation of his concept of law). [13] Second, although Marx often uses the terms synonymously, [14] a ‘barrier’ (Schranke) is not quite the same thing as a ‘limit’ (Grenze), in that a barrier (unlike a certain conception of limit) can always in principle be overcome.

Furthermore, the existence of certain inherent limits (relative to formal possibility) is not in itself a barrier to infinite expansion. There is no contradiction in the idea of an infinite expansion within limits. Taken in the context of the multiplicity of tendencies counteracting breakdown or collapse, there are thus scant purely theoretical grounds for believing in its necessity. As Marx put it: ‘[The] process would soon entail the breakdown of capitalist production, if counteracting tendencies were not constantly at work.’ [15] However, whatever position one takes in this debate, the literature on Marx on crisis, from Maksakovsky’s 1928 The Capitalist Cycle to Lebowitz’s 2008 Following Marx, [16] is agreed on one thing: in so far as Marx has a ‘theory’ of crisis, it is a critical political economic theory of crises in capitalist production. In so far as ‘crisis’ has a political meaning for Marx, though, it is in its relation to the broader historical process of a transition to a new, non-capitalist mode of production (‘social revolution’). In this respect, ‘crisis theory’ is necessarily inadequate to the thinking of crisis required, even if one were to believe that it establishes the inevitability of ‘breakdown’ (which I do not; which is not to say that such a breakdown might not come about – in which case, socialism remains far less likely an outcome than barbarism). Analysis of the historical process demands not merely an account of fundamental contradictions and their expression in conflicts and crises, but an account of crisis as a condition of possibility of the new, in this case the qualitatively historically new: new forms of social production, new relations of production and forms of organization. Crisis ‘theory’ is thus in principle inadequate to thinking the historico-political meaning of crises – and this includes Marx’s own account (or ‘theory’) of capitalist crises, however central to such a thinking it might be.

Hence my reluctance to think of Marx as a crisis ‘theorist’, with respect to the politics of crises, which was his ultimate concern.

It is a failure to adhere to the disjunction between forms of analysis here (historical development of the mode of production beyond its own limits, on the one hand, and political economy of capital, on the other) that generates the quasi-theological notion of a ‘final’ crisis of the capitalist system, as a whole, as some kind of event, rather than a process with a duration of many decades, if not centuries, appropriate to the idea of a ‘social’ rather than a merely ‘political’ revolution. And it is this notion that lies behind the substitution of a theory of breakdown for a (generational) politics of transformation. Nonetheless, the political significance of the concept of crisis motivating Marxist debates depends upon some projected articulation of these two levels, some conjunctural political effectivity at the level of the mode of production, in response to ‘periodic’ crisis. It is the assumption of such an articulation that has led, historically, to charges of ‘economism’ and ‘determinism’ being laid against Marx’s work, despite the fact that the projected mechanism of articulation is, precisely, not economic but political – namely ‘struggles’ directed towards the reappropriation of the collective powers of social labour. This is a ‘mechanism’, if one may continue to call it that – a mechanism for the transformation of conjunctural crisis into structural change – which falls outside the ‘theory’ of crisis as such. Rather, as Balibar argued back in the 1960s: ‘The analysis of the transformation of the limits … requires [minimally, we might add – PO] a theory of the different times of the economic structure and of the class struggle, and of their articulation in the social structure.’ [17] It is the current near-total absence of the social conditions for such a politics of reappropriation, of course, that has reduced the politics of crisis to that of the state’s management of the interests of ‘capital in general’, in antagonism with those of particular capitals (currently, mainly banking capital) – making crisis almost exclusively an intra-capitalist affair. Hence the current debates regarding the extent to which certain financial instruments, such as credit derivatives, threaten the ongoing expanded reproduction of the system, in a structural manner, and the extent to which what we are seeing is simply another periodic crisis in the spiral of expanded reproduction, in which capital has run up against a barrier of its own making, and thereby set itself the task of overcoming it, as the condition of a new cycle of accumulation. There is no reason, in principle, to believe that it cannot achieve this task, with the coordinated help of the major capitalist states; albeit at considerable cost to the lives of working populations.

At the outset, then, we can discern basic temporal distinctions between the way the concept of crisis functions at three levels: (1) the longue durée of history (transition between modes of production), (2) the theory of crisis as part of the political economy of capitalism (the theory of ‘the cycle’), and (3) actual, concrete conjunctures, such as the current ‘global financial crisis’, as it is called. In fact, this crisis is arguably more of a crisis of the money-form of capital (of the radical diversification and speculative intensification of forms of ‘money’) set off, in part, by the unforeseen consequences of various technical alternatives to the perceived unreliability of the US dollar as a store of value. [18] Any account of crisis adequate to Marx’s political desire – which was constituted at the level of history – would involve, minimally, the articulation of these three temporalities. [19]

However, maintaining these distinctions between levels and hence objects of analysis, and further investigating the concept of crisis in its fundamental political meaning at the level of its greatest historical generality, was not the way the literature on ‘crisis theory’ responded to the supposed economism of the traditional Marxist version. Rather, especially since the 1970s, the response has been what one might call a Weberian methodological turn in crisis theory toward a pluralization of types of crisis, not just within political economy (most notably, James O’Connor’s 1973 The Fiscal Crisis of the State20), but societally.

Jürgen Habermas’s Legitimation Crisis (also 1973) was an important text in this regard, with its multiple classifications of types of crisis, setting out from the distinction between system and lifeworld, and moving on to distinguish economic crisis, rationality crisis, legitimation crisis and motivation crisis. [21] In his 1987 survey, The Meaning of Crisis (a book that singularly fails to discuss, precisely, the question of meaning), O’Connor synthesizes such approaches via further generic distinctions between economic crisis, social crisis, political crisis and personality crisis. [22] This kind of typologizing particularization takes the meaning of crisis for granted and simply seeks instances of it, empirically, in a largely descriptive manner.

But what of the generality and fundamentally historical character of the concept of crisis? At this point, it is useful to take a brief digression via Koselleck’s historical semantics, in order to remind ourselves of the kind of concept that crisis is. I shall draw on three texts here: Koselleck’s 1959 Critique and Crisis: Enlightenment and the Pathogenesis of Modern Society, his 1982 entry for ‘Crisis’ in the 8-volume Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe/Basic Concepts in History, and the more recent essay ‘Some Questions Regarding the Conceptual History of “Crisis”’, into which the results of the latter are condensed. [23]

Historical-Semantic Digression: Koselleck

It is the virtue of Koselleck’s semantic history to have shown how in its contemporary, all-pervasive lifeworld sense, the concept of crisis dates specifically from Europe in the eighteenth century, as one of a set of categories constitutive of the emerging discourse of the philosophy of history – including, crucially, both progress and revolution, in its modern historicalpolitical meaning. On Koselleck’s account in Critique and Crisis, the Enlightenment concept of critique, which developed within the terms of the absolutist state, transformed ‘history’ into a utopian philosophical concept, by virtue of the dislocation of the subjects of critique (the Illuminati) from any possible political action, within the constraints of absolutism. For Koselleck, all philosophy of history is thus constitutively Utopian. [24] The critical process of enlightenment is thereby seen to have ‘conjured up’ a historical concept of crisis by virtue of the alienation of criticism from history. History presents itself as crisis because it demands a decision or an intervention that the critical subjects in question (the Illuminati) lacked the means to undertake. In this respect, the inherited etymological meaning of crisis as something that ‘presses for a decision’, and an intervention, becomes transferred onto – and is made in the name of – the philosophical concept of history itself. Or to put it another way (which Koselleck himself does not): crisis is constituted as a historical category according to a structure of thought within which it is speculatively political (that is, it has a political meaning) but is nonetheless, in any particular instance, political y irresolvable (that is, is not amenable to political action). The historical concept of crisis thus registers an aporia in the historical concept of politics. In other words, what I earlier called ‘the crisis of Marxist political thought’ runs far deeper than Marx’s work, down to the bedrock of all philosophic historical concepts of political practice.

In the eighteenth century, the concepts of ‘progress’ and ‘revolution’ offered alternative resolutions to this sense of history as crisis, within the terms of Enlightenment philosophy of history. It is the historical and philosophical failure of these two alternatives that now turns ‘crisis’ back onto the philosophical concept of history and the aporia of politics out of which it emerged; albeit only for so long as any particular crisis lasts. As Koselleck put it:

It is in the nature of crises that problems crying out for solution go unresolved. And it is also in the nature of crises that the solution, that which the future holds in store, is not predictable. The uncertainty of a critical situation contains one certainty only – its end. The only unknown quantity is when and how.

The eventual solution is uncertain, but the end of the crisis, a change in the existing situation – threatening, feared and eagerly anticipated – is not. [25]

In being extended to history, the concept of crisis is thus objectivized in a manner that goes beyond both knowledge of it and any possible practice. This perhaps explains why, as Koselleck notes, the terms ‘criticism’ and ‘crisis’ appear to be mutually exclusive in polemical use. [26]

Historically, in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, what was originally a single Greek concept fractured into the separate ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ components of ‘criticism’ and ‘crisis’, respectively. The indeterminacy associated with the notion of ‘crisis’ is the result of the projection of the etymological core of the term (from the Greek krinõ, meaning to cut, to select, to decide, to judge – a root it shares with the term ‘criticism’) beyond its original jurisprudential context of a situation calling for a decision (in which a decision could, indeed had to, be made), into a situation in which a decision cannot be made, because (at least on Koselleck’s account of the politics of the Enlightenment) there is no possible appropriate subject. This is an account that projects the political consequences of the underdevelopment of Prussia in the eighteenth century into the heart of the concept of Enlightenment itself.

It was the restriction of the term ‘crisis’ to a medical use in medieval Latin (based on the ancient usage in Hippocrates and Galen) – whereby it denoted the crucial, or ‘critical’, life-or-death stage in the development of a disease, at which point a decision had to be made – that introduced a distinctive existential tension into the term; while it was the apocalyptic element of its theological usage – which extended the legal context to judgement before God – that prepared the ground for its extension to history as a whole. [27] Political thought thereby became, via the concept of crisis, the diagnosis of history. Yet, for Koselleck at least, there is no doctor to intervene:

the question of the historical future is inherent in the concept of crisis only as a problem, or horizon, never as a solution.

Marx’s innovation in the discourse of crisis was to posit a solution immanent to the conditions of the crisis itself – for him, initially, the world-historical role of the proletariat, and, subsequently, the collective worker. It is not possible here to address the notorious, ongoing question of the ‘blocked’ historical role of such political subjects in fundamental social – that is, historical – change, except in the briefest and broadest of ways.

Its parameters have changed significantly since Marx’s and Koselleck’s days, both empirically and theoretically (especially with regard to the concept ‘subject’).

In the first place, in line with Marx’s own historical projection, the post-1989, tendentially global, extension of the field of operation of capital accumulation has brought about a convergence of the concept of history with that of historical capitalism: an ongoing reduction of history to historical capitalism. However, despite this, in many ways stunning, empirical confirmation of Marx’s long-term historical vision, the problematic of the collective worker as historico-political agency on a global scale, which has consequently been posed anew, on new spatial grounds, nonetheless remains primarily theoretical, formal, speculative or purely potential, for all the hopes raised by such place-holders as ‘the multitude’, ‘multitudes’, ‘movements of movements’ and the like. For there is an aporia here: the more effectively global the collective worker becomes, the less politically actual it is.

The standard explanation for this phenomenon, modelled on the effect of imperialism on the European working classes at the time of the First World War – namely, the ability of nation-states to articulate workers’ interests primarily in national rather than class terms – retains its relevance. Indeed, this relevance is heightened by the broadening geopolitical distribution of the elements of the labour process.

However, this is not the sole or even perhaps the primary problem; and the spatial dynamics of political identification with regard to states are also being transformed in myriad and complex ways. Equally, and in the long term probably more, important is the role in the formation of social subjects in capitalist societies played by abstract social and economic forms.

Capitalistic sociality (the grounding of social relations in exchange relations) is essentially abstract: primarily, a matter of form rather than collectivity. Collectivity is produced by the interconnectedness of practices, but the broadest forms of interconnectedness and dependencies that are produced exhibit the structure of a subject (the unity of an activity) only objectively – that is, in separation from both individual subjects and particular collectivities of labour – at the level of states and beyond. Not only does the subject-structure of capital no longer correspond to (although it must still articulate itself across) the territorially discrete entities of nation-states, but the dominant forms of economic subjectivation (of individuals as constituents of variable capital and consumers of commodities) are now accompanied by forms of financial subjectivation (of individuals as subjects of loans, credit-card debt, pensions, benefits, etc.) that further subsume labour to capital in the sphere of its circulation. As Harvey has put it, in another context: ‘There is a sense … in which we have all become neoliberals.’ [28] In other words, there are ‘counteracting tendencies’ not just to crises of accumulation but to the formation of collective social subjects through capitalist production as well. What are the socio-political tendencies counteracting financial subjectivation? With regard to the temporality of crisis, the cyclical character of crises of accumulation tends to instil less a sense of possibility than of repetition. This serves to reinforce the main form of temporal abstraction associated with the experience of commodities in capitalist societies: ‘the new’. The periodic character of crisis and the commodity-form each produce modes of experience of temporal abstraction that undermine or erode the historical experience of crises and, thereby, function to repress the political possibilities they contain.

It is these structures and experiences that underlie the ontological generalization of crisis in Nietzsche’s concept of eternal return. Eternal return, we can say, following Benjamin, is an allegory of the experience of capitalism. Capitalism appears here in Benjamin’s work in the figure of ‘the torments of hell … “pains eternal and always new”’. [29]

crisis, repetition, the new

‘Permanent crises do not exist.’ [30] It is the tendency towards and potentiality for crisis that is permanent, not the crisis itself. The crisis is but a regular ‘phase’ in the process of capital accumulation (der Krisenphase), alternating with ‘prosperity’ [31] – a phase that renews the conditions of accumulation. In the concept of modernity we find both a normalization and a valorization of crisis as a means of production of the new, at the level of pure temporal form, in which what appears to capital wholly quantitatively (a return to the production of surplus value) is experienced qualitatively, as newness itself. Modernity became the central category of the philosophy of history, after Hegel, via the extraction of the formal structure of temporal negation from the totalizing narrative of necessary development in Hegel’s philosophy of history. Modernity/Neuzeit (literally, new time) is a consciousness of time that is consequently simultaneously and paradoxically constitutive of history as development and de-historicizing, in its abstraction of the temporal form of the present as the time of the production of the new (negation). [32]

This valorization of the formal structure of temporal negation is the cultural correlate and psychic deposit of the real abstraction of labour-time as a measure of value.

Marx famously celebrated this experience of capitalism as modernity in The Communist Manifesto both analytically (as a ‘constant revolutionizing of production’) and performatively, in what was more or less his invention of the manifesto as a cultural political form. [33] However, this was prior to his analysis of the fetishism of the commodity form and the historical process of the commodification of novelty as the means for the capitalistic appropriation of desire.

Under these conditions, the production of the new appears not only as a central part of the progressive historical function of capitalism – the development of human powers – but also a means for its eternalization. This is what Benjamin called ‘the new as the ever-selfsame’, and about which Adorno wrote that it ‘represses duration’. [34] In repressing duration, the new negates a condition of possibility of crisis generating actual y qualititatively historical new social and political forms.

The fetishism inherent in the commodity-form represses the social labour of production. Crises seem, at first, to restore the historical temporality of capitalism – and the social temporality of labour – to experience; but, in their seriality and constancy, their subjection to the abstract temporality of the modern, crises threaten to negate it once again, at a higher level, through a normalizing repetition. It is this repetitive element in the temporality of crisis that is absolutized and thereby ontologized in the later Nietzsche: history is reduced to a new ‘affirmative’ sense of pure becoming, the constant becoming of the new. In Nietzsche, every moment is a moment of decision. This is the philosophical basis of Negri’s self-undermining politicism. For in rejecting negation as the dialectical–logical means of giving determinacy to the new, each decision merely reproduces the transcendental structure of the new as the same: the nihilism that lurks within all modernisms – a negative nihilism of the new without significant differences, as opposed to the reactive nihilism of conceptual difference of the Hegelian dialectic, against which Nietzsche was reacting.

Nietzsche’s solution was to embrace – and thereby transvalue – the condition, in the doctrine of eternal return: the imperative that, when you will something, you will to do it an infinite number of times. Such a return is acknowledged to be ‘the most extreme form of nihilism’, but, in ‘completing’ nihilism, it is understood to break its connection to reactive forces, negating their function of conservation (‘the same’) and converting them into forces of active self-destruction. In this respect, Nietzsche is the prophet of a Schumpeterian ‘creatively destructive’ capitalism. In the eternal return, nihilism is, he writes, ‘vanquished by itself’. [35] To will the eternal return was for Nietzsche to become active.

The consequence, however, is that while ‘the new’ may no longer be ‘the same’, it is also no longer new, in the sense of being qualitatively historical y new. In the eternal return, the new consumes itself, and with it time itself.

Both Hegel and Nietzsche, in their very different ways, absolutized the temporality of the new to the point of the dissolution of historical time, and with it the very notion of qualitative historical novelty upon which it depends. Yet the new itself, qua new, is abstract: ‘it gives no satisfaction’, as Marx put it. The notion of the ‘qualitatively historically new’ harbours a structural contradiction between the production of the qualitative heterogeneities to which it refers and the sameness of its own conceptual form. Yet it is in its very abstraction that the new is the emblem of the promise of a future, a future beyond the abstractly new, in which, on Marx’s imagining, wealth will have becomethe absolute working out of creative potentialities… the development of al human powers as such [as] the end in itself … [w]here humanity … [s]trives not to remain something it has become, but is in the absolute movement of becoming. [36]

This is the Nietzschean aspect of Marx’s own image of a post-capitalist condition: the new freed from the historical conditions of its emergence in capitalism’s ‘constant revolutionizing’ of the instruments of production ‘and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society’. [37] In this respect, the modern is a capitalist cultural form, even – perhaps especially – as it points beyond its current capitalistic conditions of existence.

The new, we might say, is the capitalistic form of the post-capitalist future. Benjamin recognized this in the 1930s when he interpreted Nietzsche’s idea of eternal recurrence as the transformation of the historical event into ‘a mass-produced article’ on the model of fashion as ‘the eternal recurrence of the new’. He attributed the ‘sudden topicality’ of the idea of eternal return in the 1930s to the accelerated succession of capitalist crises, whereby ‘it was no longer possible, in all circumstances, to expect a recurrence of conditions across any interval of time shorter than that provided by eternity’, leading to ‘the obscure presentiment that henceforth one must rest content with cosmic constellations’. [38]

For Benjamin, the political secret of Nietzsche’s eternal return was thus to be found in the anticipation of it by Blanqui in Eternity via the Stars (1872) – his last book, written in prison, which, Benjamin writes, ‘presents the idea of eternal return ten years before Nietzsche’s Zarathustra – in a manner scarcely less moving than that of Nietzsche, and with an extreme hallucinatory power’, but in which ‘the terrible indictment that [Blanqui] pronounces against society takes the form of an unqualified submission to its results.’ This is the ‘novelty as hell’ of the ‘Conclusion’ to the 1939 Exposé of Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century. [39] We remain exposed to this ‘unqualified submission’ to the capitalistic terms of the crisis – restoration of accumulation through depreciation and the destruction of capital and the further disciplining of labour and everyday life – today.

Notes

1. ^ David Yaffe, ‘The Marxian Theory of Crises, Capital and the State’, Bul etin of the Conference of Socialist Economists, Winter 1972, pp. 5–58; Andrew Gamble and Paul Walton, Capitalism and Crisis, Macmillan,

London, 1976; Union of Radical Political Economists, United States Capitalism in Crisis, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1978; Paul Mattick, Economic Crisis and Crisis Theory, Merlin, London, 1981; Simon Clarke, Marx’s Theory of Crisis, Macmillan, London, 1993.

2. ^ Rick Kuhn, Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism, University of Illinois Press, Champaign, 2007; ‘Economic Crisis, Henryk Grossman and the Responsibility of Socialists’ (his Memorial Prize Lecture), Historical Materialism, vol. 17, no. 2, 2009, pp. 3–34; Michael Lebowitz, Fol owing Marx: Method, Critique and Crisis, Brill, Leiden and Boston, 2008, Part 3; Samantha Ashman et al., ‘Symposium on the Global Financial Crisis’, Historical Materialism, vol. 17, no. 2 (2009), pp. 103–213.

3. ^ Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part 2, Lawrence & Wishart, London, 1969, p. 528.

4. ^ Antonio Negri, ‘The Constitution of Time’ (1981), in Time for Revolution, trans. Mat eo Mandarini, Continuum, London and New York, 2001, pp. 54–5.

5. ^ Theories of Surplus Value, Part 2, p. 497.

6. ^ Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), trans. Martin Nicolaus, Penguin/New Left Books, Harmondsworth, 1973, p. 415; Theories of Surplus Value, Part 2, p. 528.

7. ^ Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 3, Book 3, ‘The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole’, Lawrence & Wishart, London, 1959, p. 249; Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, Drit er Band, Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin, 1964, p. 259.

In this instance, the Lawrence & Wishart (L&W) translation is preferable to the later, usual y more reliable,

Penguin edition. Cf. Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 3, trans. David Fernbach,

Penguin/New Left Review, London, 1981, p. 357.

8. ^ Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1, Book 1, ‘The Process of Production of Capital’, trans. Ben Fowkes, Penguin/New Left Review, Harmondsworth, 1976, p. 770, translation amended; Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, Erster Band, Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin, 1962, p. 648. Fowkes neglects to translate the ‘itself’ [selbst], which (as Étienne Balibar has pointed out to me) Roy’s 1875 French translation strengthened to ‘spontanément’.

9. ^ Marx, Capital, Volume 3, L&W, p. 250; Karl Dietz Verlag, p. 260; cf. Penguin, p. 358.

10. ^ Marx, Capital, Volume 3, L&W, p. 246; Karl Dietz Verlag, p. 256; cf. Penguin, p. 355.

11. ^ Marx, Capital, Volume 3, Penguin, p. 358; Karl Dietz Verlag, p. 260; cf. L&W, p. 246.

12. ^ David Harvey, ‘Introduction to the 2006 Verso Edition’, in The Limits to Capital (1982), Verso, London and New York, 2006, p. xxi .

13. ^ Cf. Étienne Balibar, ‘Elements for a Theory of Transition’, in Louis Althusser and Étienne Balibar, Reading Capital (1968), trans. Ben Brewster, Verso, London and New York, 1979, p. 291n.

14. ^ See for example, Grundrisse, p. 416.

15. ^ Marx, Capital, Volume 3, Penguin, p. 355, translation amended; Karl Dietz Verlag, p. 256. For an at empt to enrich and update Marx’s account of crises and the counteracting tendencies through which they are resolved, with respect to, first, the post-World War II development of finance capital, and second, its geographical aspects, see Harvey, The Limits to Capital, ch. 10, section X, and ch. 13, sections V and VI, respectively.

16. ^ Pavel V. Maksakovsky, The Capitalist Cycle: An Essay on the Marxist Theory of the Cycle (1928), trans. Richard B. Day, Bril , Leiden and Boston, 2004; Lebowitz, Fol owing Marx.

17. ^ Balibar, ‘Elements for a Theory of Transition’, p. 293.

18. ^ As argued, for example, by Dick Bryan in his contribution to the panel ‘Derivatives’ at the Historical Materialism conference, London, 29 November 2009.

19. ^ It is in the transition from the analysis of ‘Tendency and Contradiction in the Mode of Production’ to ‘History’ that Balibar’s ‘Elements for a Theory of Transition’ runs up against the internal limits of the Althusserian problematic, for which ‘history’ is not itself considered a concept of the theory of history, but rather only of its epistemology. Reading Capital, p. 302.

20. ^ James O’Connor, The Fiscal Crisis of the State, Palgrave Macmil an, New York, 1973. See also his Accumulation Crisis, Blackwel , Oxford, 1984.

21. ^ Jürgen Habermas, Legitimation Crisis, trans. Thomas McCarthy, Heinemann, London, 1976.

22. ^ James O’Connor, The Meaning of Crisis: A Theoretical Introduction, Blackwel , Oxford, 1987.

23. ^ Reinhart Kosel eck, Critique and Crisis: Enlightenment and the Pathogenesis of Modern Society, Berg, Oxford/New York/Hamburg, 1988; ‘Crisis’, trans. Michaela W.

Richter, Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 67, no. 2, April 2006, pp. 357–400; ‘Some Questions Regarding the Conceptual History of “Crisis”’, in Reinhart Koselleck, The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts, Stanford University Press, 2000, ch. 14, pp. 236–47.

24. ^ Critique and Crisis, pp. 11–12, 185.

25. ^ Ibid., p. 127.

26. ^ Ibid., p. 168.

27. ^ Koselleck, ‘Crisis’, pp. 358–61; ‘Some Questions Regarding the Conceptual History of “Crisis”’, pp. 237–40.

28. ^ Harvey, Limits to Capital, p. xiii. Harvey is writing about the ‘widespread acceptance of the benefits to be had from the individualism and freedoms that a free market supposedly confers’, but his account neglects issues of subjectivation.

29. ^ Walter Benjamin, ‘Paris, Capital of the 19th Century:

Exposé of 1939’, in The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London, 1999, p. 26.

30. ^ See note 5.

31. ^ Marx, Capital, Volume 1, pp. 770–71; Karl Dietz Verlag, p. 648.

32. ^ See Peter Osborne, ‘Modernism and Philosophy’, in Peter Brooker et al, eds, The Oxford Handbook on Modernism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, forthcoming 2010, ch. 20.

33. ^ See Peter Osborne, ‘Remember the Future?: The Communist Manifesto as Cultural-Historical Form’, in Philosophy in Cultural Theory, Routledge, London and New York, 2000, pp. 63–77.

34. ^ Walter Benjamin, ‘Central Park’, in Selected Writings, Volume 4: 1938–1940, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA and London, 2003, p. 175; T.W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (1970), trans. Hul ot-Kentor, Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis, 1997, p. 27.

35. ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, The Wil to Power, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R.G. Hol ingdale, Random House, New York, 1968, pp. 1053, 1056, 58,

28. ^

36. ^ Marx, Grundrisse, p. 488, translation amended. Cf. Peter Osborne, ‘Marx and the Philosophy of Time’, Radical Philosophy 147 (January/February 2008), pp. 15–22, p. 17. Marx’s modernism was historico-philosophical, or part of an historical ontology of the human, rather than ontological as such.

37. ^ Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848), in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Volume 6, Lawrence & Wishart, 1976, pp. 477–512.

38. ^ Benjamin, ‘Central Park’, pp. 166–7, 178.

39. ^ Benjamin, ‘Paris, Capital of the 19th Century: Exposé of 1939’, The Arcades Project, pp. 25–6.

Rebalancing the Economy, Refurbishing the State: The Political Economic Logic of Sino-Capitalism in Contemporary China

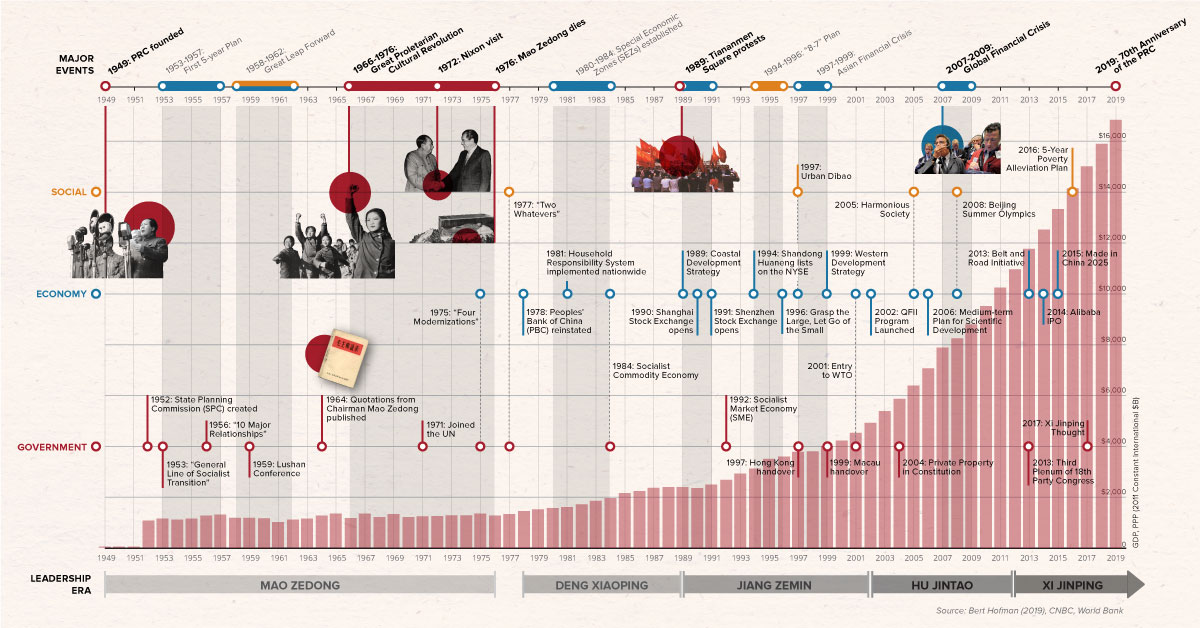

China represents a highly significant case that can inform debates on the nature and logic of capitalism, especially those expressed in the wider Comparative Capitalisms (CC) literature. This is not just because of China’s sheer size and international economic influence, but also because China’s form of capitalism – Sino-capitalism – opens up new avenues for theoretical inquiry in CC. Specifically, Sino-capitalism’s constitution demonstrates the importance of Régulation Theory’s more open and evolutionary approach to understanding CC.

Sino-capitalism conceives China’s political economy as driven by the dialectic of top-down state-centric modes of governance interacting with bottom-up networked modes of entrepreneurship based on market competition. This contrasts with the more static comparative approaches in most of the CC literature. In particular, this conception highlights how compensatory institutional complementarities are central to understanding CC. To illustrate Sino-capitalism’s dynamic of reproduction, the article looks at recent policy initiatives that aim to rebalance China’s development model. Even though rebalancing incorporates more forceful economic liberalization, retaining and strengthening state control over crucial areas of socio-economic governance is central. China is therefore pursuing a policy package that seeks to strengthen state governance capacity and market forces in tandem, illuminating the chronic re-composition and rebalancing of institutional spheres via top-down/bottom-up dialectics shaping Sino-capitalism.

Introduction

China’s stunning economic transformation over the past 35 years still poses a puzzle for social scientific analyses. How could China’s obviously state-dominated development model produce such economic dynamism? Indeed, how has sustained market liberalization been combined with concerted efforts at strengthening state control over crucial areas of economy and society? And how has China undertaken far-reaching internationalization of its economy without sacrificing key elements of domestic policy autonomy?

In this article, I argue that the puzzle of China’s political economy can serve to inform salient debates on the nature and logic of capitalism highlighted in the Comparative Capitalisms (CC) literature (Deeg and Jackson, 2007; Jackson and Deeg, 2006; 2008). So far, conceptualizations of the crucial case of China remain at odds with each other and have found little resonance in the CC literature. For sure, most analyses of China in comparative political economy and economic sociology agree that China is, in fact, developing a form of capitalism. However, how to incorporate China’s form of capitalism both comparatively and theoretically in the CC literature remains a major challenge (Fligstein and Zhang, 2011; Peck and Zhang, 2013).

This challenge is also reflected in how CC literatures have so far faced difficulties in conceptually integrating emerging market economies. The narrow binary conception of Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) (Hall and Soskice, 2001) into Liberal Market Economies (LMEs) and Coordinated Market Economies (CMEs) never aimed to comprehensively cover emerging markets. Recent efforts within the CC literature have started to fill this conceptual gap. Much of the work has concentrated on Eastern Europe and, to a lesser extent, Latin America and East Asia (Bohle and Greskovits, 2012; Boyer et al., 2012; Hancké et al., 2007; Noelke and Vliegenthart, 2009; Noelke et al., 2014; Schneider, 2013).

All of these works go beyond the highly seductive parsimony of a binary distribution into LMEs and CMEs espoused by mainstream CC literature. Similarly, my analysis sees China as generating a novel form of capitalism – Sino-capitalism (McNally, 2007; 2012; 2015). Sino-capitalism’s analytical framework employs an open (Becker, 2009; 2014) inductive qualitative approach that conceives of “variegated” capitalisms globally (Jessop, 2012; Peck and Theodore, 2007; Streeck, 2010) and builds directly on insights in Régulation Theory (Aglietta, 1976; Lipietz, 1992; Boyer, 1990; 1997; 2005; Boyer et al., 2012). There is accordingly no “base” model of capitalism, but rather an assemblage of unique varieties of capitalism embedded in the global capitalist system.

I proceed by introducing the logic of Sino-capitalism, broadly conceived of as the macro-structural dynamics that define the mode of reproduction (cf. Boyer, 1990) and shape China’s contemporary political economic evolution. I then illustrate the dynamics driving Sino-capitalism’s institutional reproduction with recent policy initiatives that aim to rebalance China’s development model. Finally, the conclusion develops theoretical insights that can be generated from analyzing and conceptually extending the logic of Sino-capitalism.

My theoretical findings incorporate a call for more open and dynamic approaches that focus on the role of the state, the international embeddedness of national capitalisms, and the existence of contradictory/symbiotic politico-economic logics driving capitalist evolution. Quite pointedly, any conception of capitalist political economies must recognize the existence of different politico-economic spheres, each with its own logic or “Eigengesetzligkeit” (Weber, 1978; cf. Oakes 2003). Interactions among these spheres can generate a multiplicity of dynamics, ranging from symbiotic, reinforcing, counterbalancing, and compensatory, to contested and in discord.

Consequently, institutional complementarities under Sino-capitalism are not primarily conceived of as existing in a reinforcing state. Rather, compensating institutional complementarities have dominated and created dialectical dynamics of mutual adaptation and tension-ridden conditioning (cf. Evans, 1995). Sino-capitalism’s evolution thus represents an intriguing case of 35 years of extremely rapid and transformational institutional change that nevertheless exhibits a profound constant: a central dialectic of top-down state-guided capital accumulation existing side by side with bottom-up networks of entrepreneurs, market competition, and global economic integration.

1. The Logic of Sino-Capitalism

Most of these accounts stress one single aspect of China’s political economic evolution, but consequently miss the most central facet: the dialectical evolutionary dynamic of counterbalancing institutional complementarities driven by state guided forces top-down, by entrepreneurial networked forces bottom-up, and by global economic integration outside-in. In China’s emergent capitalism, state and private sector forces have mutually conditioned each other. The logic of Sino-capitalism attempts to capture these basic modalities of how China’s economic dynamism and political regime are replicated over time.

Analytically, the logic expresses the macro-structure shaping institutional and political reproduction, which, in turn, gives rise to China’s unique accumulation regime and modes of regulation. Insights from Régulation Theory (Aglietta, 1976; Lipietz, 1992; Boyer, 1990; 1997; 2005; Boyer et al., 2012) resonate directly in this conception. Paralleling other cases of capitalist evolution, China faced a critical juncture during the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s as the Maoist regime’s legitimacy was questioned. A series of major political decisions to address this crisis created a new politico-economic compromise: private capital, both foreign and domestic, was gradually welcomed in China’s economy under the continued dominance of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This compromise, in turn, shaped the evolution and hybridization of specific sets of institutions defining Sino-capitalism.

In this context, the logic of Sino-capitalism can only be understood by conceptualizing China’s political economy as experiencing rapid international economic integration, especially intense participation in global value chains. Sino-capitalism forms by now an interdependent part of the neo-liberal global capitalist system. And finally, as Régulation Theory emphatically argues, capitalism does not tend towards stable equilibria, but rather is characterized by constant tensions and crises generated by its modes of reproduction. The dialectical logic of Sino-capitalism illustrates this volatile nature of capitalism strikingly.

The manner in which different institutional spheres interact means that Sino-capitalism differs from traditional conceptions of capitalist variety in important respects. Sino-capitalism is reproduced by a contradictory or dialectical quality: state-guided capitalism is tempered and at times challenged by dispersed private entrepreneurial forces that have created one of the world’s most dynamic and globalized private sectors. Sino-capitalism’s logic of reproduction thus derives from a specific institutionally-based notion of China’s emergent capitalism. Distinct institutional spheres are conceived of as interacting and mutually conditioning each other.

As a result, Sino-capitalism represents a distinctive institutional amalgam. Global integration, bottom-up networks of entrepreneurs, and top-down state guidance all coexist and balance each other’s dynamic elements, generating unique and diverse institutional complementarities. To illustrate, under Sino-capitalism’s eclectic policy outlook prices and market mechanisms are merely tools to an end: to develop China and make it wealthy and powerful. There is no a priori adherence to “free markets” as in a belief that fully liberalized market forces will generate the most efficient outcomes. Rather, controlled (often localized) policy experimentation is widely employed under long-term guiding principles. Most Chinese reforms have therefore constituted a work-around: they have employed measured market liberalization, though always under the condition that effective degrees of state control over the domestic economy remain intact.

The following develops further our understanding of Sino-capitalism’s logic by concentrating on three crucial sub-logics. Firstly, the central logic of reproducing a structurally rather stable dialectic of counterbalancing institutional spheres; secondly, and following from this sub-logic, a deliberately cautious pace of change that avoids radical departures from the past and tries to assure comprehensive state control over the reform process; and, finally, the interplay of state-centric development planning with local initiatives and policy trials bottom-up, a process that has generated much needed political space for economic experimentation and institutional innovation.

The propagation of a structurally rather stable dialectic which juxtaposes top-down state-guided capitalism with bottom-up networks of entrepreneurs, market competition, and global economic integration shapes Sino-capitalism’s logic most deeply. Although undergoing fundamental reform and massive growth, China’s political economy has continuously reproduced and recalibrated this dialectic. Chinese economic reform processes are accordingly not characterized by the dominant and stifling role of state-centric governance (Huang, 2008). Neither are they purely driven by entrepreneurial network-led accumulation from below (Nee and Opper, 2012). Counterbalancing institutional complementarities have actually conditioned, pressured, and mutually self-generated each other. These institutional spheres and their logics are sometimes in discord, but more often coexist and balance each other’s strengths and weaknesses (cf. Evans, 1995).

Critically, the logic of Sino-capitalism depends on the continuous adaptation of the CCP and Chinese state formations (Tsai, 2007; Dickson, 2008; Shambaugh, 2008). Chinese state firms, for example, began far-reaching reforms only after the development of private and quasi-private firms eroded their monopoly profits during the 1980s (Naughton, 1992). However, rather than attempting to smother private entrepreneurship, policy makers after 1992 concentrated on more fundamental restructurings of the state sector. State firms retreated from the most competitive and least profitable sectors in the Chinese economy, but kept a tight grip on industries populating the “commanding heights.”

The evolution of Sino-capitalism, therefore, does not represent a unilateral retreat of the state in favor of private entrepreneurial and market forces. Neither is it a story of initial liberalization followed by a full reassertion of statism (cf. Huang, 2008). The best way to understand Sino-capitalism’s dialectical logic is to focus on how private capital accumulation put pressures on the state to reform and adapt. State-initiated reforms and experimentation in turn enabled further private sector development, creating dynamic cycles of induced reforms, where each small step at restructuring created demands for further modifications (cf. Jefferson and Rawski, 1994; Naughton, 1995; Solinger, 1989).

In this view, top-down Leninist incentives focused on economic performance prodded local governments to compete vigorously for investment capital. This inter-jurisdictional competition led to the gradual liberalization of China’s economy and triggered substantial improvements in the investment climate facing both domestic private and foreign investors. In fact, state capitalist guidance and vibrant private entrepreneurship have tended to meet at the lower levels of the state apparatus, where local cadres have played a crucial role in accommodating and supporting individual capitalist accumulation.