Archive

Notes on Marx’s “General Law of Capitalist Accumulation”

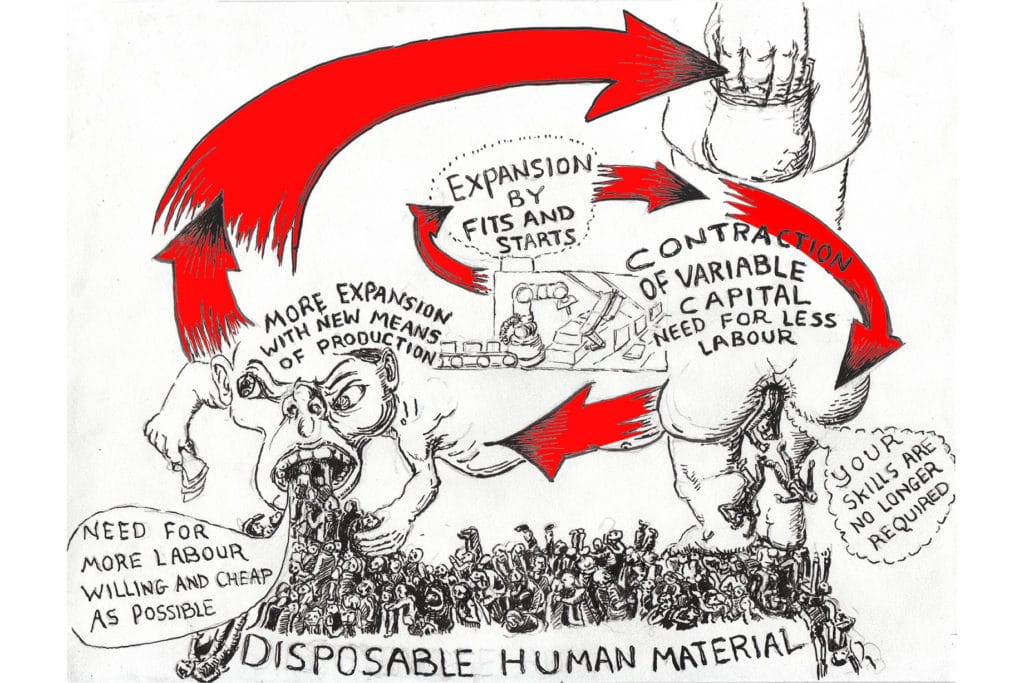

“Disposable Human Material,” illustrating the role of the surplus population (or reserve army of labor) in the extraction of value from workers, inspired by Chapter 25 of Karl Marx’s, Capital. This is just a small taste of a wonderful series of drawings created to illustrate Marx’s laws of motion of capital. There is at least one illustration for each chapter of Capital, vol. 1! The drawings were created by the Capital Drawing Group based in London, UK.

Andy Merrifield

June 19, 2019

If someone were to ask me what my favourite bit of Marx’s Capital is, I’d tell them Chapter 25, on “The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation.” Not that anybody has ever asked me; but I suspect I wouldn’t be alone in selecting this pinnacle performance, the beginning of the climatic unfurling of Volume One. For here those “laws of motion” that Marx had been trying to lay bare throughout Capital, really do motor before the reader’s very eyes, in all their disturbing fluidity. Hitherto, Marx had been attempting to piece together the intricate “inner mechanisms” of capitalist society. By Chapter 25, he’s ready to analyse these inner mechanisms as a giant well-oiled whirring machine.

And he’s mesmerised by the prodigious power of this machine, by capital accumulating, bursting through every historical and geographical restriction, conquering the entire world of social wealth. Yet, at the same time, he’s appalled by the ruthless force it unleashes, by the horrors the machine inflicts upon its cogs. Meanwhile, its normal functioning soon takes on a spiraling dynamic all its own, operating beyond the control of any single capitalist master. After a while, the enviable freedom of the capitalist gets transformed into a die-hard necessity, into an infamous historical mission:

Accumulation for accumulation’s sake, production for production’s sake.

The drive to accumulate capital dramatically pits capitalist against capitalist, capitalist against worker, worker against worker. Accumulation fuels competition, and competition, Marx says, “subordinates every individual capitalist to the immanent laws of capitalist production, as external, coercive laws.” Thus, as capitalists strive to accumulate, as their actions become mere functions of capital, they inevitably clash with other capitalists seeking to do likewise. What erupts is a fratricidal war; different fractions of capital jostle one other, struggle to corner markets, to control and monopolise markets, to control and monopolise labour; a zero-sum accumulation mania transpires and conspires. Accumulation is the centrifugal impetus of “capital in general.” But competition hastens a splintering of capital, just as it hastens a splintering of labour, compounding each side into many “aliquot parts.” Thus, as capital accumulates, the formation and intensification of class structure manifests itself as a paradoxical obliteration of class structure.

Before long, the hullabaloo of accumulation is “supplemented” by concentration and centralisation, by big capitalist fishes gobbling up little fishes and sharks chomping on big fishes. Marx says this enhances the scale of operations, accelerates the overall effects of accumulation, but in uneven ways, for capitalists and workers alike. Trouble and strife brood. For, on the one hand, competition and the obligatory development of a credit system become powerful levers of centralisation—of the formation of joint stock companies, trusts and conglomerates, mergers and acquisitions—and of expanded accumulation; on the other hand, though, the “organic composition of capital”—the ratio of dead to living labour, of machines to workers, of constant to variable capital—gradually starts to creep upwards, diminishing the relative demand for labour.

Before long, too, the system breeds a new species: Marx labels them “a new financial aristocracy, a new variety of parasites in the shape of promoters, speculators and nominal directors, a whole system of swindling and cheating by means of corporation promotion, stock issuance, and stock speculation.” Could Marx be talking about us? By God yes. Nowadays, we know these people by name, by sleazy reputation; we know, too, that within the overall accumulation process this new financial aristocracy has a stake very different to that of productive capital’s.

The former plays an extremely limited, if any, enabling role for valorisation: stock exchanges are now billion dollar markets for speculating on already existing stocks and shares. Little activity here actually raises money for new productive investment. Businesses generate money by selling stock and shares, relinquishing part of the company to shareholders; but little of the accruing booty gets recycled into future investment. Invariably, it’s doled out as dividends, and/or creamed off through inflated CEO salaries.

***

One of the reasons I like to affirm Chapter 25 isn’t only because it explains the working conditions of the world’s peoples today; it also explains the conditions of our whole existence. Marx’s general law of capitalist accumulation is nothing less than the lever upon which all our lives now pivot. Its frame of reference needs to be opened out, out onto the broader canvas of life, especially planetary urban life. The mighty machine has made us cogs everywhere. It’s here where I’d like to develop Marx’s law, “a law of tendency,” as he calls it, which expels people from dwelling space as well as from the workplace. As such, this law isn’t just a condition of earning a living; it’s a condition of earning a life.

Marx knew in the 1860s that “the absolute” general law of capitalist accumulation could be “modified in its workings by many circumstances.” But in every case, he says, it “followed that in proportion as capital accumulates, the situation of the worker, be their payment high or low, must grow worse.” In our present-day “neoliberal” context, the economy flourishes through sub-employed and over-employed workers, through contingent and gig economy workers, through zero contract hours workers: from Uber to Deliveroo, Handy to Hermes, Amazon to Adjunct Professors, work is evermore casualised and irregular; and worker benefits seem to diminish by day. Toilers here assume that category Marx reckons the general law of capitalist accumulation progressively produces: “a relative surplus population”—or, alternatively, “an industrial reserve army of labour.”

“Every worker,” Marx believes, “belongs to this relative surplus population during the time when they are only partially or wholly employed.” Marx, it’s worth pointing out, sees all work under capitalism as precarious; always has been, always will be. It’s a precariousness dependent on a consistently fickle capitalist business cycle, on short-term soars and long haul dips. Wage levels, he says, get regulated by the relative surplus population, by its expansion and contraction. Wages “aren’t determined by the variations of the absolute numbers of the working population,” Marx insists,

but by the varying proportions in which the working class is divided into an active army and reserve army, by the increase or diminution in the relative amount of surplus population, by the extent to which it is alternately absorbed and set free.

Sometimes wages might even rise should demand for labour rise. At these moments, wages can conceivably keep increasing so long as they don’t impinge upon the overall expansion of capital. Something resembling this actually occurred during the boom of the 1950s and 1960s, when real workers’ wages did in fact rise. Still, the more typical rule, Marx thinks, is that “the mechanism of capitalist production takes care that the absolute increase of capital isn’t accompanied by a corresponding rise in the general demand for labour.” “Capital,” he says, does something more innovative instead, something more dialectical: it “acts on both sides at once”:

If its accumulation on the one hand increases the demand for labour, it increases on the other the supply of workers by ‘setting them free’, while at the same time the pressure of the unemployed compels those who are employed to furnish more labour, and therefore makes the supply of labour to a certain extent independent of the supply of workers. The movement of the law of supply and demand for labour on this basis completes the despotism of capital.

And under this despotism, real wages have effectively stagnated, almost nowhere keeping pace with cost of living hikes. One of the U.S.’s top capitalist mouthpieces, TheHarvard Business Review(October 24th 2017), admits that hourly inflation-adjusted wages for the typical American worker have, since the early 1970s, hardly risen, edging upwards a mere 0.2% per year. Throughout this period, remember, the overall economy has been growing. Thus American workers haven’t participated in any of the growth, nor benefited from gains in their own productivity. The reason why is classic Marx Volume One: new technology has put downward pressure on less-skilled workers’ wages; and workers displaced from work send disciplinary messages to those still active in work: work harder or else!

Whether in times of prosperity or decline, the industrial reserve army produces much the same effect: “it weighs down the active army of workers; during periods of over-production and feverish activity, it puts a curb on their pretensions.” The relative surplus population is,

the background against which the law of the demand and supply of labour does its work. It confines the field of action of this law to the limits absolutely convenient to capital’s drive to exploit and dominate workers.

***

If we dig a little deeper into Chapter 25, we can see how Marx identifies three types of relative surplus population: stagnant, floating, and latent. Alas, we haven’t got to dig too deeply, nor have too much imagination, to see how Marx’s types remain our types. The stagnant form, for a start, is “part of the active labour army,” he says, “but with extremely irregular employment. Hence it offers capital an inexhaustible reservoir of disposable labour-power.” It’s characterised “by a maximum of working time and a minimum of wages.” The downsized blue-collar worker might be filed under this category, since stagnant surplus populations, Marx says, are,

recruited from workers in large-scale industry who have become redundant, and especially from decaying branches of industry where handicraft is giving way to manufacture, and manufacture to machinery.

This stagnant workforce consists of time-served men repulsed from blue-collar employment and drawn into irregular jobs like security and custodial work, janitors, cabbies and deliverymen. Older generation blue-collar workers, who once worked the mines, the auto plants and steel mills, now find themselves literally stagnant. They’re no longer able (or willing) to do low-grade work, yet are too young to retire. So instead they slouch into the ranks of a non-participating labour-force. Men who once set rivets together now sit alone, able to recite daytime TV schedules by heart. Utter stagnation lingers everywhere in rust-belt Europe and America, where empty union halls look out over the rubble of what used to be the company plant.

The dialectic of the floating relative surplus population is similarly one of repulsion and attraction, but its charge is much more volatile. Participants here encounter working conditions wholly unstable and uncertain. The only thing that’s regular is the irregularity of their work. These men and women represent a huge pool of under-employed and sub-employed workers—part-time, on-call, self-employed or zero hours contractors—whose resumé is marked by a floating in and out of jobs. Despite the job-hopping, few new skills are ever learned. Steadily, its fluctuating force assumes a predictably deadening life-form. Many workers are absorbed into the “personnel services industry,” where the hiring and firing is managed by employment agencies like Manpower, Inc., who recruit temporary workers across America and the world. (Manpower has offices in fifty countries, and places 1.6 million “in assignments with more than 250,000 businesses worldwide annually…providing our customers with productive workers and our employees with work.”) The growth of this personnel services industry means evermore despotic control of an anarchic labour-market. Supply and demand for labour tightly track the expansions and contractions of capital; yet always its motioning seeks to trim monies laid out on variable capital.

As at May 2017, the U.S.’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) said nearly 6 million workers are “contingent”—i.e. “persons who do not expect their jobs to last or who report that their jobs are temporary.” Moreover, there are a further 10.6 million people working as “independent contractors,” together with another 2.6 million on-call. And this doesn’t include 1.4 million temporary help workers nor the 933,000 employed by contract firms like Manpower. Which suggests that true numbers for contingent America total up to somewhere in the region of 20 million people. No coincidence, too, that the nation’s two largest employers are contingent kings Walmart and McDonald’s.(1)

Techie giants like Google, often seen as egalitarian employers with idyllic workplaces, are likewise massively reliant on temporary and contracted labour. In fact, “a shadow workforce of temps” now outnumber Google’s full-time employees. As at March 2019, Google uses 121,000 temp and contracted workers, compared with a full-time workforce of 102,000. Google temps are employed by outside agencies and, in the U.S., make less money than Google full-timers. They have different benefits packages and no paid vacation. Last April, hundreds of Google employees signed a letter protesting the company’s “two-tier system,” as well as the dismissal of 80 percent of a 43-person artificial intelligence team of contingent workers. OnContracting, a temp employment agency for the high-tech industry, says that companies like Google save $100,000 a year on average per American job by using a temporary contractor instead of a full-time employee.(2)

Women swell the ranks of this floating contingent workforce. In the U.S., women are three times as likely to hold regular and irregular part-time work as men. These women make up about a fifth of the overall female workforce, earning, on average, 20 percent less than equivalent women employed full-time and 20 percent less that their male counterpart part-timers. Minority groups fare worse than their Anglo peers, and minority women worst of all. On the whole, African-American women tend to be twice as likely to be lower paid temps and much less likely to be self-employed; Hispanics, meanwhile, have a larger share of low-wage “on-call” work.

Capitalism has a handy knack of constantly inventing and reinventing its reserve army of labour. Often it does so miraculously, tapping into assorted branches of society and sectors of industry where labour has been lying latent. Thus, alongside the stagnant and floating forms, Marx acknowledges another category of flexible labour, the “latent” category, a sort of reserve reserve army of labourers. “As soon as capitalist production takes possession of agriculture,” he says, “and in proportion to the extent to which it does so, the demand for a rural working population falls absolutely.” “Part of the agricultural population,” says Marx,

is therefore constantly on the point of passing over into an urban population or manufacturing proletariat. There is a constant flow from this source of the relative surplus population. But the constant movement towards towns presupposes, in the countryside itself, a constant latent surplus population.

The movement of peoples from rural to urban areas, from agriculture to an urban-based factory system, continued apace during the twentieth-century. As at 2006, its flow tipped the global demographic balance: the majority of the world’s inhabitants, some 3.3 billion people, live in urban agglomerations, not rural areas. Some of that generation’s latent surplus populations, i.e. people formerly displaced from agriculture and reabsorbed into urban factories, have since fallen into the ranks of floating and stagnant relative surplus populations. Yet by 2030, 60% of the world’s population is projected to be urban; an additional 590,000 square miles of the planet will be urbanised, a land surface more than twice the size of Texas, spelling an additional 1.47 billion urban dwellers; many of whom will bolster the ranks of a latent reserve army. They’ll offer sustained nourishment for expanded capitalist accumulation everywhere.

A big chunk of this latent surplus population lurks in China. Shanghai is the planet’s fastest growing metropolis, expanding a massive 15 percent each year since 1992, boosted by $120 billion of foreign direct investment. Half the world’s cranes are reputed to be working in Shanghai’s Pudong district. Rice paddies have been filled with modern skyscrapers and vast factories. Outlying farmlands now host the world’s fastest train links and the tallest hotel. Four thousand buildings with twenty or more stories have gone up, ensuring Shanghai has twice the number of buildings as New York. With 171 cities of more than one million inhabitants, China over the past decade has commandeered nearly half the world’s cement supplies, and will doubtless monopolise the world’s supply and demand for latent surplus labour populations.

Of course, after 1989, with the tumbling of the Berlin Wall, another reservoir of latent labour flooded the capitalist marketplace. A freshly- proletarianised workforce initiated a primitive accumulation of capital, transforming former Eastern European state employees into freelance wage-labourers, set free to pit their wits on the flexible European labour market. The Eastern bloc’s headlong embrace of Western-style neoliberalism prised open a whole new array of market niches, together with a jamboree latent labour reserve—both at home, in some newly-formed nation-states, and in the European Economic Area (EEA). Almost overnight an ideology of dictatorial personality morphed into an ideological dictatorship of the free market, with its attendant rights of consumerist man.

Out of the ashes of communism rose the Phoenix of cheap labour. Western manufacturers, halving labour costs, beat a hasty path eastwards; while a lot of latent labour, almost as hastily, trekked westwards. Stimulated by the European Union’s freedom of labour movement (2004), they’ve found low-grade jobs in powerhouses like Britain, Germany and France. Pay is better than before, yet a lot less than homegrown workers’. British businesses have prospered enormously from this influx of Eastern European labour, especially Polish. Enterprises have been able to valorise a cheap labour they’d not had since the 1950s, when Afro-Caribbean Windrush immigrants arrived. The British agricultural sector has been a big gainer. Prior to 2004, crops like asparagus, cherries, raspberries and strawberries were suffering long-term decline. Remuneration in these sectors was meagre; the work backbreaking. Few locals were turned on. Yet since 2004, rather than invest in expensive new berry-picking technology, growers have exploited Eastern European labour reserves, latent labour-power, which has rekindled agricultural capital accumulation and boosted productivity.

***

When Marx formulated his General Law of Capitalist Accumulation, cities were sites for manufacturing valorisation. It was in urban factories where commodities got produced and surplus value created. The factory system—“Modern Industry,” Marx called it—was the mainstay of capital accumulation, and workers were attracted and repelled from this urban employment. Later in Chapter 25, however, Marx notes how the general law operates outside the factory gates as well—vividly exemplified, he says, in “‘improvements’ of towns which accompany the increase in wealth, such as the demolition of badly built districts, the erection of palaces to house banks, warehouses, etc., the widening of streets for business traffic, for luxury carriages, for the introduction of tramways, [which] obviously drive the poor away into even worse and more crowded corners.”

It’s not a bad description of what still happens in big cities today. Marx’s point here is “that the greater the centralisation of the means of production, the greater is the corresponding concentration of workers within a given space; and therefore the more quickly capitalist accumulation takes place, the more miserable the housing situation of the working class.” Landlords squeeze workers, ripping them off at home, as tenants, just as industrialists rip them off at work, as wage-labourers. Rents are high precisely because pay is low. Vulnerable workers equate to vulnerable tenants; both feel the force of “property and its rights,” Marx says. “Everyone knows,” he adds, “that the dearness of houses stands in inverse ratio to their quality, and that these mines of misery are exploited by house speculators with more profit and less cost than the mines of Potosi were ever exploited. The antagonistic character of capitalist accumulation, and thus of capitalist property-relations in general, is here so evident.” Marx’s adopted hometown of London, one of world’s richest cities, had the most squalid, overcrowded habitations, “absolutely unfit for human beings,” he says. Marx knew this because he and his family lived in many of these hovels. “Rents have become so heavy,” he cites one government health inspector saying, “that few labouring men can afford more than one room.” 1865 or 2019?

And yet, in another sense, a lot has changed since Marx’s day. Back then, his focus was on production in the industrial city; a century and a half on, the city itself has become the form of industrialisation. In the 1860s, cities were places where commodities got produced; nowadays, cities are themselves commodities, centres of gravity for the General Law of Capitalist Accumulation and for the expansive power of capital. Now, urban space itself is both the subject and object of valorisation, the means of production as well as the product this means of production creates. In manufacturing, Marx said new technology would prompt a change in the “organic composition of capital.” “The growth in the mass of means of production,” he argued, “as compared with the mass of labour-power that vivifies them, is reflected in its value-composition by the increase of the constant constituent of capital at the expense of its variable constituent.”

So, too, now, is the organic composition of capital in cities rising. Quite literally rising. Constant capital is displacing variable capital: capital circulates into the construction of new fixed capital assets, new items of the built environment, such as office blocks and shopping malls, Hudson Yards and Coal Drops Yard, upscale housing and elite cultural amenities—high-yield activities for the expanded reproduction of capital rather than low-yield necessities for the simple reproduction of labour-power. This is the sense in which workers have now been set free from life, not just from work: they’re displaced from dwelling space as they are rendered superfluous from the workplace.

The progress of urban accumulation lessens the relative magnitude of the variable part of capital, even if, as in industry, it can’t lessen it entirely. Capital, after all, needs its minion service workforce of busboys and valet parkers, of waiters and barmen, of cleaners and security guards, of nannies and cooks, of superintendents and doormen. But a push-pull effect has taken hold, a dialectic of attraction and dispossession, a sucking into the city of a relative surplus population together with a spitting out, a banishment from the centre. Poor old-time stagnant populations, as well as floating and latent reserve armies, now embrace one another out on the periphery somewhere, where rents are lower and life cheaper.

This system produces planetary geography as a commodity, as a pure financial asset, using and abusing people and places as strategies to accumulate capital. The process embroils everybody, no matter where; even when it doesn’t embroil, even when it abandons people and places, it embroils. Cities, like the factories of Marx’s era, become vortexes for sucking in everything the planet offers: its capital and power, its culture and people—its dispensable labour-power. It’s this sucking in of people and goods, of capital and information that fuels the urban accumulation machine, that makes it so dynamic as well as so destabilising. For it’s a system that secretes a residue, chewing people up when needed, spitting them out when they’re not.

Residues are something more than relative surplus populations and probably include a fair number of lumpenproletariat. They’re minorities who are far and away a global majority. They’re people who feel the periphery inside them, who identify with the periphery, even if sometimes they’re located in the core. Residues are workers without regularity, workers without any real stake in the future of work. Residues are refugees rejected and rebuked, profiled and patrolled no matter where they wander. Residues are those whose land has been grabbed, who’ve been displaced from housing, thrown out of housing, whose living space teeters on the geographic and economic edge. Residues are disenfranchised and decommissioned people everywhere who feel isolation strike them deep within. Residues come from the city as well as the countryside and congregate in a space that is often somewhere in-between, neither traditional city nor traditional countryside. We might call this somewhere in-between the globalbanlieue. (Remember, the French word banlieue comes from lieu, meaning “place,” and bannir, “to banish”; hence “place of banishment.”)

A lot of these residues know that now work is contingent life itself is contingent. And with little security, there’s little to lose, and, moreover, little to gain from playing by capitalism’s rules. So what’s the point? There is no point. Some residues play by different rules, beat a different drum. Others listen to reactionary demagogues and swing right, embrace populist ravings against the machine. Many others voice muffled hopes from the left. All somehow know the capitalist game is rigged, that those in power are liars and cheats. Still more residues know that a career of hustling and hawking, of wheeling and dealing, of petty criminality, of opioids and outlawing, become coping mechanisms from the outside to a life that offers no discernible future on the inside.

One of the problems Marxists face—and I think Marx knew it might one day become a big problem—is that many residues have lost their class address. How can they regain it, find the right door bell to ring on together? How can workers who have no Party, no regular workplace or arena for collective bargaining—in fact who have no real public arena at all—how can they find one another? Perhaps the more vital question is how can the twenty-first century “dangerous classes” become really dangerous? How can they endanger the capitalist system rather than just endanger themselves?

Notes

- Walmart’s low-wage workers are so poor that they receive around $6.2 billion in federal assistance, principally in the shape of food stamps. The billionaire Walton business thus gets a huge public handout for its low-balling employment practices. In a recent study, conducted by the Organization United for Respect (OUR), 55 percent of Walmart part-timers admitted they didn’t have enough money to meet basic needs.

- See “Google’s Shadow Workforce: Temps Who Out Number Full-Time Employees,” The New York Times, May 28, 2019.

State and Capital in the Era of Primitive Accumulation

Jairus Banaji

In the second, posthumous volume of Sartre’s masterpiece, The Critique of Dialectical Reason, which is largely given over to the attempt to make deeper sense of Russia’s industrial expansion under Stalin, that is, to the problem of how a command economy works, Sartre explains that the best history is defined as a synthetic movement or what he calls “totalizing compression”. He writes, “two dialectical procedures are possible on the basis of an identical social reality. On the one hand, a procedure of decompressive expansion which starts off from the object to arrive at everything … in this case thought may be called detotalizing and the event loses out to the signified ensembles. On the other hand, a procedure of totalizing compression which, by contrast, grasps the centripetal movement of all the significations attracted and condensed in the event or in the object”.1 I want to suggest in this lecture2 that we need to integrate Marx’s notion of primitive accumulation into a wider history of capitalism that allows for the combined nature of its evolution, and that one way of doing this is to treat primitive accumulation as one of those “practical significations” or “signified ensembles” or structures that form a permanent dimension of capitalism. This means breaking with the linearity of the simplified model of primitive accumulation that many Marxists still subscribe to, with its “stagism” if you like, and with the strong resonance of teleology that usually goes with that. Retrospective readings of capitalism start with large-scale industry and imagine that primitive accumulation explains how that came about. But, if there is a sense in which this may account for Britain’s industrial primacy, it is hard to see how it would “explain” most other industrial trajectories which were in any case influenced by Britain’s own expansion, either correlatively (as in India) or by negation (as with Britain’s main industrial competitors). In a critique of Marx’s pages, Gerschenkron made a great deal of this point, noting that the bank-financed industrial expansion that occurred in Germany did not presuppose anything like the protracted processes Marx had described.3 But, if my general suggestion is accepted, the obvious question of course is – what wider history? Do we have the categories for that? And how exactly do we see primitive accumulation fitting into this broader canvas?

It may help to start by dispelling possible misconceptions. At the level of national capitals, there is no inevitability which says that primitive accumulation will always succeed. Thus Spanish mercantilists such as Alberto Struzzi and Sancho de Moncada were relentless in their criticisms of Spain’s backwardness;4 Spain, in the later 16th and 17th centuries, offers a striking demonstration of the failure of primitive accumulation, precisely because nothing was as emblematic of this “original” accumulation as Spain’s amassing of American treasure and the pure predation and brutality involved in the way that was done. Spain amassed gold and silver but failed to convert this accumulated mass of precious metals into capital. Thus “Moncada urged Spain to emulate France and Holland, countries without mines, in which, because of industry and active commerce, gold and silver abounded”;5 and the naturalised Spaniard Struzzi wrote in 1624, “It is absurd to expect money to stay in Spain. It is needed in trade. The Dutch and others pay for goods in money, but it then returns to them by other paths through trade. There is no nation rich without trade”.6 For primitive accumulation to have succeeded, Struzzi was telling his readers, Spain would have had to have had a class of commercial capitalists strong enough to match the competition of “the Dutch and others”; yet, if we look at the Mediterranean as a whole, the two regions where no substantial class of indigenous capitalists ever emerged, at least not in a serious way, were precisely the great empires ruled over by the Spanish Habsburgs and the Ottomans, including cities like Naples that were under Spanish rule.7

Secondly, the amassing of a large capital stock even in the more advanced countries was not a sufficient condition of industrial capitalism. In the Netherlands, in the eighteenth century, “rapidly accumulating stocks of capital” led in fact to the financial sector becoming an “important sector of the economy in its own right”, as Jan de Vries tells us.8 Here, of “the large capital stock amassed by a century of profitable expansion … [l]ittle new investment found its way into industry”. It flowed instead into doubling the size of the VOC in the face of new competition from the French and English, into establishing a Caribbean plantation economy, and into a new type of whaling enterprise which faced higher capital requirements as the whaling grounds retreated further north.9 In the case of England, Christopher Hill had asked, “Where did the capital for the Industrial Revolution come from?” and replied, “Spectacularly large sums flowed into England from overseas – from the slave trade, and especially from the seventeen-sixties, from organized looting of India”.10 Yet Hill went on to make the point “it is not always easy to trace connexions so directly. There is not much evidence that the plunder of India flowed directly into industry: much of it was spent on conspicuous consumption, and on buying political immunity for the plunderers”.11 This puts paid to Marx’s implied suggestion that the “plunder” of Bengal by the servants of the East India Company who legally engaged in private trade was directly instrumental to industrial expansion in Britain. In East Indian Fortunes Marshall calculated that “£3,000,000 was sent home before 1757 and about £15,000,000 over the 27 years between 1757 and 1784”, but notes, about those who returned to Britain from Bengal, “Few … regarded their fortunes as capital for further venturing in trade or manufacturing in Britain”.12

Thus, the narrow sense in which many non-Marxist scholars, economists more than historians, understand “primitive accumulation”, namely, as the accumulation of capitals which are then channelled into industrial development13 is a misconception of the broader sense in which Marx himself understood this dimension of capitalism’s history. Primitive accumulation was viewed by him both as a long and violent history of dispossession, of what he called the “terrible expropriation” of the “great mass of the people from the soil”14 and as a process of consolidation of capital. Much of Marx’s attention was, of course, given over to the first side of this long “pre-history of capital”,15 but Chapter 31, which deals with the consolidation of capital, alludes to a very wide range of topics that include colonial trade and the colonial system, public finance, indirect taxation, commercial wars, protectionism, child labour, and the slave-trade. However, the overall impression a reader comes away with is that primitive accumulation was to Marx’s mind a sort of long “pre-history” of industrial capitalism as this had developed by the 1860s. The main drawback of this model in this stark form is its linearity. Centuries of violence and dispossession, and of states intervening to consolidate capital, are followed, in the way Marx tells this story, by the eventual triumph of large-scale industry. But the fact that Marx’s last chapter dealt with Wakefield suggests that he extended this narrative into the 19th century to include settler colonialism in his history of primitive accumulation at a time when Britain at least was widely thought to be suffering from a ‘superfluity’ or overaccumulation of capital,16 and, following this cue, I want to suggest a more complex or “combined” history of capitalism that allows, as I said, for the simultaneity of capitalism and primitive accumulation. A good example of this method is the way Rosa Luxemburg describes Russia in the 19th century. She notes that in Russia “big industry staged its real entry” only in the last two decades of the 19th century and goes on to say, “‘Primitive accumulation’ of capital flourished splendidly in Russia, encouraged by all kinds of state subsidies, guarantees, premiums, and government orders”, placing the expression itself in quotes.17 Again, the state is central to the process.

To allow for this history of capitalism, however, we need to establish a clear distinction between two forms or “determinations of form” that Marx himself tends either to conflate or to ignore. Marx saw what he called manufacture and the manufacturing period as signifying the emergence of industrial capital. In an interesting passage of the Grundrisse that I shall return to, the period of mercantilism is described as “an epoch where industrial capital and hence wage labour arose in manufactures”.18 Now, it is true that in the seventeenth century industrial production acquired new, enhanced, significance, for example, in the writings of those like the Calabrian Antonio Serra who saw state-supported production of manufactured exports as the most effective way of securing surpluses on the current account and the best form of a mercantilist policy.19 But, stated the way Marx does, this ignores the fact that these were largely merchant-controlled enterprises. As late as the eighteenth century, luxury-goods industries such as the Lyons silk industry were dominated by merchant’s capital, by the so-called marchands-fabricants studied by Carlo Poni in one remarkable paper.20 Those firms used the putting-out system and a battery of designers to generate the sort of flexibility that allowed them to dominate the European fashion market to the despair of competitors in England and Italy. In fact, as early as 1929, Henri Hauser had signalled the distinction involved here by writing, “at the end of the fifteenth century new industries appeared, the children of the Renaissance; war industries like the production of guns, luxury industries like silk; intellectual industries like printing, type-making and paper-making… It would, perhaps, be premature to speak of industrial capitalism… But let us at least speak of commercial capital being applied to industry”.21 Now, “commercial capital applied to industry” is not industrial capital in the sense in which the owners of modern large-scale industry have come to personify this. It seems more plausible to reserve the term “industrial capital” for enterprises that were run by manufacturers who were no longer merchants. In the US this transition was still ongoing in the 19th century cotton industry22 and there industrial capital proper only truly emerged in the shape of the large vertically integrated enterprises in oil, steel, chemicals, rubber and so on, that came about towards the very end of the nineteenth century.23 The same is true of the development of industry on the Continent, for example in Germany where industrial capitalism exploded in the early 1870s as bankers like Bismarck’s friend Bleichröder came around to financing that “great expansion”.24 In any case, the merchant-controlled manufacturing enterprises of the late medieval and early-modern periods cannot be seen as industrial capital in this stricter, modern sense.

In volume 3 of Capital, there is a passing reference to “the manner and form in which commercial capital operates where it dominates production directly”.25 The two examples Marx cites of this are first “colonial trade in general (the so-called colonial system)”, that is, the vast transatlantic commercial system which among other things revitalised slavery as a modern development, and secondly, “the operations of the former Dutch East India Company”; in short, two very substantial trade sectors in both of which Marx seemed to think commercial capital was active in new, more “direct” ways. As important as this text is another. “Industrial capital has value for them, even the highest value”, Marx says about the mercantilists in the Grundrisse passage that was cited earlier, “because it creates mercantile capital and the latter, via circulation, becomes money”.26 Now, it is this creation of mercantile capital via “industrial capital”, that is, via production, that forms the stable heart of the pre-industrial regime, and I’d like to suggest that it is plausible to see merchant or commercial capitalism as a system of accumulation where merchant capitals are characterised by this tendential drive to subordinate production directly. Of course, since the biggest commercial firms were always highly diversified business enterprises that moved capital between finance, trade and manufacturing, the expansion of mercantile capital in this pure sense was part of more complex strategies of accumulation. It might make sense to see merchant capitalism as characterised by “sectors”, of which the four or five main ones were (1) the Verlag-based manufacturing that first sprawled across large parts of the countryside of western and central Europe as early as the thirteenth century, reaching an absolute zenith in the eighteenth; (2) the big concentrated money-markets which moved in sequence from Venice to Antwerp to Genoa to Amsterdam and finally to London; (3) the commercial investments that went into trade sectors such as the Atlantic and Asia; in the Atlantic the productive capital financed by merchants took the form of plantations and slavery; and (4) the produce trades that were the typical form of British mercantile capitalism in the 19th century and characterised by advances to household producers circulated either directly (as in the Government’s monopoly of “Bengal” opium) or more generally through local brokers who were usually substantial indigenous merchants in control of their own networks. In Many-headed Hydra, Linebaugh and Rediker describe shipping as a “mode of production that united all of the others in the sphere of circulation”,27 and since most shipping magnates were also merchants, at least before the emergence of specialised shipowning in the late 18th century,28 shipping should likewise be seen as a purely merchant-capitalist sector, a fifth one. The flexibility and sophistication of the bigger merchant firms lay not just in their minute knowledge of international markets but in their ability to move between sectors and combine them in various ways. On the other hand, the vast mass of lesser commercial capitals specialised within particular sectors, e.g. the London agency houses that financed much of the West Indian trade, or the cambisti or bankers who dominated Europe’s exchanges, starting with the very substantial money-market in Venice that was controlled by Florentine banks,29 and so on.

Today, we are in a much better position to flesh out some of the more abstract intuitions of Marxists like Preobrazhensky. When he argued that “the whole period of the existence of merchant capital” should “be regarded as a period of primitive accumulation, of the systematic plundering of petty production”,30 what he had in mind were sectors 1, 3 and 4 I have outlined above, basically Verlag + the colonial trades. By “plunder” he simply meant what Arghiri Emmanuel would later call “unequal exchange”, that is, enforced control over terms of trade in a world marked by mobility of capital/immobility of labour, for example, by holding the wages of weavers down, as all merchant capitalists were able to do when they monopolised raw materials. But Preobrazhensky situated himself in a tradition of historiography shaped by Franz Mehring’s views of merchant capital as the “revolutionary force of the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries”, one that “not only created modern absolutism but also transformed the medieval classes of society”.31 In Russia, this strand of history was best represented in the work of M.N. Pokrovsky, and Preobrazhensky showers praise on him when dealing with primitive accumulation.32 It is also there in Isaak Rubin’s lectures on economic history.33 Pokrovsky himself continued to maintain, as late as 1929, that “Commercial capitalism played a huge role in the creation of the Russian monarchy. It created this Russian absolute monarchy”,34 a position he was soon forced to retract. Thus when later historians like Georges Lefebvre posited a crucial “symbiosis between the State and the merchants” and argued that it was “the collusion between commerce and the State (that) promoted the development of capitalism” (this was the stand Lefebvre took in the transition debates),35 or, when Mousnier suggested that the absolute monarchies and large-scale capitalism were “functions of each other”,36 the same dissident historiography was being articulated. Indeed, Maurice Dobb himself devotes a whole chapter of Studies in the Development of Capitalism to what he calls “Capital Accumulation and Mercantilism”. He argues there that mercantilism was “essentially the economic policy of an age of primitive accumulation”, “a system of State-regulated exploitation through trade which played a highly important role in the adolescence of capitalist industry”.37 The peculiar nexus between state and capital reflected in the fluid array of mercantilist policies that have their origins in the later middle ages and reach their culmination in the seventeenth century seems to me to best describe the political economy of primitive accumulation.38

Before coming to this, however, let me say a bit about three of the five sectors I listed above. Putting-out networks were the “first hard evidence of a merchant capitalism”, Braudel wrote in Wheels of Commerce.39 Wolfgang von Stromer has argued that Verlag was the most widespread type of economic organisation in Europe before the advent of large-scale industry. The textile industries of the twelfth to sixteenth centuries and later were entirely based on it. It allowed for “export-oriented standardized mass production” and in South Germany for a concentration of production in entire industrial basins.40 In London in the seventeenth century, as Beier shows, “big City merchants” “organized craft production in the suburbs and countryside”, a development, he argues, that led “naturally to the industrial revolution because, as Dobb states, ‘[T]he capitalist merchant-manufacturer had an increasingly close interest in promoting improvements in the instruments and methods of production’”.41 In France, “concentrations of capital were in commercial form”, Lefebvre writes. “Millions of peasants worked for city merchants”.42 Picardy and Beauvais in the north of France became the base of a rural-based textile industry controlled by “powerful merchants”.43 Putting out [le travail à façon] was widespread in the Swiss textile industry of the early 19th century, as Veyssarat’s work shows,44 and outwork was still the predominant form of industrial organisation in Britain in the 1820s.45 Bythell who notes this cites Mendel’s argument that so-called “proto-industry” “created an accumulation of capital in the hands of merchant entrepreneurs, making possible the adoption of machine industry with its (relatively) higher capital costs”.46 Finally, it is worth noting Maxine Berg’s criticism that Marx’s model of manufactures was “useful in highlighting the features of some eighteenth-century industry” but it was a “linear model” and failed “to deal adequately with the features of the putting-out system and other related forms of domestic manufacture”.47 (Marx says little about putting out.)

The American plantations “were capitalist creations par excellence”, Braudel notes in Wheels of Commerce, and then clarifies, “[i]t was European trade that commanded production and output overseas”.48 London’s expansion in the late 17th century was fuelled by the plantation trades. But to start with, it is worth noting that “in terms of both capital value and overseas trade, the slave system was expanding, not declining, at the turn of the nineteenth century”.49 “Twice as much money was invested in the slave trade during 1791–1807, at the height of the abolitionist agitation, as in the agitation-free decades 1761–1780”.50 British slave-trade capital, Drescher argues, rose sharply at the end of the eighteenth century.51 “There was little vocal opposition to the trade between the sixteen-fifties and the loss of America, not even from Quakers”.52 In the plantations themselves, next to slavery, the critical relation of production was merchant economic control over planters. The total sum owing to London merchants by West Indian sugar planters, for example, was several million pounds by 1770, roughly as much as the total mercantile debt owed by the mainland colonies to London at this time, viz. £3 million.53 In Cuba, the Matanzas sugar economy was largely financed by the Havana merchant houses through so-called “refacción” contracts which guaranteed sugar supplies for export.54 The bigger merchant establishments such as the Torrientes were the main accumulators of Cuban capital.55 Yet, this is not the end of the story. When Baron Alphonse de Rothschild visited Cuba in 1849, it was not the Havana merchant houses but the London merchant banks, he claimed, “who are making all of the profit from commissions, credits and consignation”. “The sugar business here is the monopoly of the (Havana) exporters… However, they are not doing the most important or weighty business, this [is] being done by Barings, Coutts, Fruehling & Goschen in London”.56And, for roughly the same reasons, in 1860 a North Carolina paper described New York as “the Northern state which had profited most by the slave labor of the South” thanks to the “commercial ties” that existed between them.57 Eric Williams was surely right to claim, “The commercial capitalism of the eighteenth century developed the wealth of Europe by means of slavery and monopoly”, and to say that “in so doing it (commercial capitalism) helped to create the industrial capitalism of the nineteenth century”.58 Williams describes a historical dialectic similar to primitive accumulation, but one in which one form of capitalism feeds into the expansion of another and destroys itself as it does so, except that it did not, as Drescher’s critique showed, since slavery continued to expand. Finally, it is worth noting that in Theories of Surplus Value Marx focuses on the planters rather than on the London houses that financed this whole web of trade. When he wrote, “the business in which slaves are used is conducted by capitalists”,59 he seemed to have the planters in mind. But in the Atlantic trades “there was a fundamental shift to the commission system” from the 1660s. British merchants supplied American planters “with a wide range of mercantile and quasi-banking services, including the provision of shipping, insurance, and eventually finance”.60 “The commission system, which was overwhelmingly centered on London, came to dominate the greater part of British Atlantic trade”.61 This explains how “at least half of the total for (Jamaica’s) import and exports made its way invisibly back to England (in freight charges, insurance, commissions, interest on debts, and transfers of money to absentee landlords). All in all, the net benefit for England in the year 1773 was getting on for £1,500,000. In London, as in Bordeaux, the proceeds of colonial trade were transformed into trading-houses, banks and state bonds”, says Braudel,62 confirming Rothschild’s point about where the profits of Cuban sugar went. Thus, Marx’s expression “conducted by capitalists” should really refer us back to a conglomeration of commercial interests at the heart of which lay the London West India houses whose judgements or instructions to the island agencies were “based on City news and outlook”.63

Finally, a third sector, the produce trades. British merchants who financed household production in India and West Africa in the 19th century did so through a system of advances. Mercantile advances embodied a circulation of capital. These were not transactions in the sphere of “simple circulation” but a means of integrating peasant household labour into the capitalist world market. Chayanov called this form of accumulation “vertical capitalist concentration”. By this he meant that “while in a production sense concentration in agriculture is scarcely reflected in the formation of new large-scale undertakings, in an economic sense capitalism as a general economic system makes great headway in agriculture”. Agriculture, he wrote, “becomes subject to trading capitalism that sometimes in the form of very large-scale commercial undertakings draws masses of scattered peasant farms into its sphere of influence and, having bound these small-scale commodity producers to the market, economically subordinates them to its influence”.64 The example Chayanov cited was of the large cotton merchants of the Knoop family. “The need to lay out money in advance made heavy demands for working capital”,65 which meant that the produce trades were characterised, over time, by a growing concentration and centralisation of capital, with giant firms like the United Africa Company (UAC, the trading arm of Unilever) dominating very large shares of the produce market in British West Africa.66 It was this sort of “vertical concentration” that sustained the largely British and French trades in palm oil, raw cotton, opium, wheat, tea, teak, rice, coffee, jute, rubber, groundnut and so on, all of which saw major periods of expansion in the mid-to-late 19th century and early twentieth.67On “very small farms” gross output per acre has always been the important calculation for households, as Krishna Bharadwaj showed for India back in the seventies; “very small cultivators” concentrate on high-value cash crops with a high labour input per acre.68 Jute was a prime example of this “forcing up of labor intensity”, as Chayanov characterised the economic behaviour of most farm households, and of course “[t]he key to making money out of jute manufacturing both in Calcutta and Dundee was to buy raw jute at as low a price as possible”.69 In parts of China the equivalent crop was tobacco, “the most valuable of all cash crops”, as Chen Han-Seng described it in a valuable study from 1939,70 except that here it was a large vertically integrated industrial firm B.A.T. or British American Tobacco that enforced the sort of price domination that held large numbers of peasant households in thrall. Prices were dictated by the company’s foreign leaf experts who were specially flown in from the US South, just as the English East India Company had, back in the eighteenth century, fixed the rates to be paid for a wide assortment of piecegoods from Bengal at their headquarters in London, two years before actual delivery, with no allowance for price increases that weavers had to contend with in the intervening period,71 and just as the French commercial houses that financed groundnut cultivation in Senegal fixed the prices to be paid to producers at their head offices in Bordeaux.72 The so-called “self-exploitation” of the peasantry fed directly into higher rates of surplus-value on these commercial capitals, and through them on the total social capital. “Is the general rate of profit raised by the higher profit rate made by capital invested in foreign trade, and colonial trade in particular?”, Marx had asked in volume 3,73 and replied of course in the affirmative. (Note that Emmanuel’s theory of unequal exchange presupposes equalisation of profits with unequal rates of surplus value, the latter thanks to immobility of the labour factor.)74

The expansion of mercantile capital was thus the standard form of capitalist accumulation for centuries together, even if this history has never been properly constructed. Any historian who does so would have to start with the fierce struggles between Venetian and Genoese capitalists for domination of the Byzantine markets in Constantinople, the Aegean and the Black Sea. But leaving that aside, it is quite clear that in the seventeenth century a major transformation took place, as the state stepped in to extend its formal backing to capital and the competition of capitals took on a much stronger “national” form. If Spanish mercantilism was a long lament on Spain’s failure to develop, the mercantilisms of France, Holland and England were quite different in character, as “[c]ommercial competition”, in the words of von Schmoller, “even in times nominally of peace, degenerated into a state of undeclared hostility: it plunged nations into one war after another, and gave all wars a turn in the direction of trade, industry and colonial gain”.75 A fascinating passage in Volume 3 refers to the commercial struggles of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as “the industrial struggle of the nations on the world market” and sees the intervention of the state as seeking to accelerate the development of capital “by compulsion”, as Marx puts it. “It makes a substantial difference”, Marx says here, “whether the national capital is transformed into industrial capital gradually and slowly or whether this transformation is accelerated in time” by the use of tariffs and “the forcibly accelerated accumulation and concentration of capital, in short by the accelerated production of the conditions of the capitalist mode of production”.76 The passage ends with Marx underscoring both the “national”, that is, nationalist, “character of the Mercantile System”, as well as its purely capitalist content, saying that the mercantilists “show their awareness that the development of the interests of capital and the capitalist class, of capitalist production, has become the basis of a nation’s power and predominance in modern society”.77

The reference to primitive accumulation is unmistakable here, but what is interesting is that Marx now situates it within the global competition of capitals and it depends more than ever on the state’s “accelerating” role. All the various “methods” of primitive accumulation that were “systematically combined together at the end of the seventeenth century in England”, Marx had written, “employ the power of the state”,78 and there is a crucial sense in which the early development of capitalism was also about the expanding power of the modern state. It was Hilferding who picked up on this in the last piece of writing he ever drafted, but I shall come to that in a moment. In its most general sense, mercantilism expressed the identity of the interests of state and capital. This of course has been described in numerous ways, as “alliance”, “collaboration”, “liaison”, “partnership”, “backing”, “support”, and so on. For example, Rubin noted “during the age of merchant capitalism a close alliance was formed between the state and the commercial bourgeoisie, an alliance which found expression in mercantilist policy”.79 The general idea is nicely expressed in the way Brenner in his best work describes the relationship between Crown and company merchants, e.g. as the “powerful state backing” that “the City’s richest and most influential businessmen” received for their voyages of exploration under Elizabeth.80 But, in the sixteenth century, England was not a naval power. By the second half of the seventeenth century, “the navy not only grew in size but became an instrument of a national policy of commercial aggrandizement”.81 This is a central part of John Brewer’s argument in his brilliant book The Sinews of Power. By the early eighteenth century “the entire British fleet amounted to a capital investment of nearly £2.25 million”,82 half the value of the total capital invested in the Atlantic trade in the 1770s. Cromwell’s “foreign policy was dominated by economic considerations”, and “[f]rom the interregnum, commercial interests acquired a primacy in the formation of foreign policy”.83 Both French and English mercantilism had grown up in the shadow of Holland’s crushing commercial superiority in the second and third decades of the seventeenth century. Montchrétien’s Treatise of Political Economy (1615) shows both his admiration for as well as the profound influence of the Dutch. A major conclusion of his tract was the need to expand the pool of skilled labour and learn from the more advanced organisation of the Dutch manufactories.84 In England, Thomas Mun demolished the illusion that money was an independent force in the economy. He wrote, “It is not therefore the keeping of our Money in the Kingdom which makes a quick and ample Trade, but the necessity and use of our Wares in Forreign Countries and our want of their Commodities…”.85 Money mattered to the mercantilists of the seventeenth century chiefly as means of circulation, as a way of boosting liquidity and increasing the velocity of circulation to expand the flow of trade. By the late seventeenth century, as the Navigation Acts and the rapid expansion of English merchant shipping tilted the balance decisively in England’s favour, commercial wealth and naval power came to be seen as “mutually sustaining”. “The object of all three Anglo-Dutch Wars was to destroy Dutch trade and shipping”,86 but the broader assumptions behind this new-found aggressiveness were precisely those of any mature mercantilist state, the need to enforce a “national monopoly of the international carrying trade and of colonial markets”, to encourage import-substitute manufactures,87 and to convert the mass of the destitute and the unemployed into a productive labour force, not least, Bacon suggested in 1625, to contain sedition among the poor.88 It was left to Christopher Hill to note that “[a]ccumulation through monopoly trade was more rapid than in industry”, and that once large sums of capital were available for industrial investment by the late eighteenth century, “the navigation system itself became superfluous”.89

France, England and the United Provinces all had strong states and even if they differed radically in form, in substance they were essentially geared to promoting the needs of capital, since the strength of the state itself was increasingly seen as a function of the strength of “national capital”, as Marx called it in the passage I cited from volume 3. Thus Nicolas Mesnager in his mémoire to the Council of Commerce dated 1700 claimed, “Monsieur the cardinal de Richelieu did not find any means more effective to increase the power of the king and the wealth of the state than to increase navigation and commerce”.90 In the Netherlands, William of Orange agreed “Commerce is the pillar of the state”, but insisted, “if the security of the state was destroyed by French territorial expansion, the ruin of Dutch shipping and trade would assuredly follow”.91 And both there and in England the growth of the national debt depended crucially on excise duties, since “debt issues were underwritten by substantial increases in the excise on items like malt and beer”,92 and the greater part of tax revenue went into servicing the debt. As Brewer says, the term “mercantilist” “does provide a useful characterisation of an era in which the relationship between state power and international trade was seen as a problem of exceptional importance”.93 In short, the growth of capitalism was as much a function of governments and their financial needs as it was of the emergence of powerful groups of capitalists in international commerce and government finance, and it is this mutuality between state and capital which best defines the era of primitive accumulation. This was as true of French absolutism as it was of the Dutch Republic and of Britain’s fiscal-military state. Indeed, one of the most striking features of his pages on primitive accumulation is that the precise form of the state scarcely seems to matter to Marx.

Gerschenkron claimed “Marxism in general found it difficult to place the mercantilistic State within its conceptual framework”, and argued that this was because “Marxism at all times had difficulty with explaining dictatorial power. Even when, as in the case of Napoleon III, the State that was not dominated by a certain class could be presented as originating from an equilibrium of class power, the problem still remained that once the dictatorial State was established, it was able to pursue an independent policy of its own, because it had become an independent power in its own right… When it comes to Russia”, he said, “[t]he overriding consideration is that it would make little sense to regard the autocratic State as emerging from [an] equilibrium of class power”.94 There is a moment of truth in this criticism, but firstly, mercantilism was not confined to the absolutist states and in England, in fact, received its strongest expression in the Interregnum. Secondly, there have been significant attempts within the more creative strands of historical materialism to address this issue of the autonomy of the state. In his last, unfinished piece of writing called “The Historical Problem” Hilferding regarded the state’s existence as a machine aware of its own special interests as the state-power as the major problem of theory confronting Marxists. Indeed, in a paradoxical but I think perfectly true formulation he argued, “State power was objectively stronger in the heyday of liberalism than it ever was in the age of Absolutism”.95 “Under mercantilism the economy is not subordinated to the State”, he writes, “on the contrary, the State becomes a means of encouraging or establishing those economic interests and tendencies that simultaneously satisfy its own needs”.96 This is essentially the view I suggested in the preceding paragraph. Thus for Hilferding the “struggle to establish the absolute monarchy and with it the modern state” was a “struggle of the State-power [ein Kampf der Staatsmacht] against the ruling class”, one that was “supported by the bourgeoisie or sections of it”.97 For his part, Sartre has a similar if less extreme view in volume one of the Critique. He argues that “the State constitutes itself as a mediation between conflicts within the dominant class”,98 “constitutes itself as the organ of the contraction and integration of the class”, but crucially it “cannot take on its functions without positing itself as a mediator between the exploiting and the exploited classes”; “it affirms itself as a deep negation of the class struggle”. “The State therefore exists for the sake of the dominant class, but as a practical suppression of class conflicts within the national totalisation”.99 This, he says, is not pure mystification, because “the State really does produce itself as a national institution … it takes a totalising view of the social ensemble”, “it already posits itself for itself in relation to the class from which it emanates: this united, institutionalised and effective group … tries to produce itself and to preserve itself in and through itself as an essential national praxis, by acting in the interests of the class from which it emanates and, if necessary, against them. One need only look at the policies of the French monarchy between the fourteenth and the eighteenth centuries to see that it did not confine itself to providing mediation when forces were evenly balanced, but rather created this balance by perpetual changes of alliance, so that the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy would control each other, so as to produce itself, on the basis of this deadlock … as an absolute monarchy”.100

Whatever we think of these views, it is clear that the prevailing instrumentalist views of the nature of the modern state will simply not work in trying to describe its role in the era of primitive accumulation. There was no coherent mercantile interest for the state to be simply a pawn in the hands of this or that sector of capital. Moreover, as Wallerstein says, the growth of the national debt “reflected the growing autonomous interests of the states as economic actors”.101 In the case of Stalin’s Russia, arguably the last great episode of primitive accumulation in modern history, it is even less possible to derive the decisions of the state from any preformed classes. Under Stalin the “methods” of primitive accumulation ranged widely from dispossessing millions of peasants and breaking the resistance of an organised working class, even forcing it back into seriality, to the use of mass repression and terror as instruments of accumulation, the paroxysm of violence in 1937, the banning of abortion and revival of the cult of the family, the personality cult, manipulations of public opinion, and so on. Much of this has been brilliantly documented in Don Filtzer’s series of monographs which covers a very wide span of Russia’s industrial experience.102 The more abstract elements of analysis are given in volume two of Sartre’s Critique, and interestingly there he cites what must remain one of the more vivid images of Stalinist primitive accumulation, namely, John Scott’s account of the monstrous squandering of labour and production that occurred at the giant metallurgical complex at Magnitogorsk in the Ural industrial region, where between 1928 and 1932 “nearly a quarter of a million people came”, the vast bulk of them voluntarily, “seeking work, bread cards, better conditions”.103 Here Scott, who worked as an electric welder for five years in the thirties, saw those masses of uprooted peasants create “a gigantic plant and city” within five years. Under Stalin, he wrote, the “tempo of construction was such that millions of men and women starved, froze, and were brutalized by inhuman labor”.104 This had nothing to do with socialism, of course, since it presupposed the disarming of the factory committees which had occurred under the Bolsheviks very soon after the Revolution;105 presupposed also the silencing of the Opposition and suppression of a free press, and later, in the 1930s, that peculiar “reciprocity of incarnations” between Stalin and the bureaucracy which Sartre tries hard to fathom in his second volume. If there were limits to Stalin’s control of the Soviet bureaucracy, it remains true nonetheless that the bureaucracy saw itself as an incarnation of Stalin and of his frenetic drive to make Russia catch up with the west at any cost.

- Sartre, Critique of Dialectical Reason, vol.2, pp. 49, 188.

- This paper was presented as a keynote at the conference on primitive accumulation organised by the Institute of Social History in Amsterdam in May 2019.

- Gerschenkron, Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective, Chapter 2, e.g., “Original accumulation of capital was not a prerequisite of industrial development in major countries” (p. 46).

- Perrotta, “Early Spanish Mercantilism”.

- Hamilton, “Spanish Mercantilism”, p. 234.

- Struzzi cited Perrotta, “Early Spanish Mercantilism”, p. 37.

- Zarinebaf, Mediterranean Encounters seeks to qualify this picture for the Ottomans, but fails to establish the presence of an influential class of merchant capitalists among the Turks.

- Jan de Vries and Ad van der Woude, First Modern Economy, p. 129.

- De Vries and van der Woude, First Modern Economy, p. 677.

- Hill, Reformation to Industrial Revolution, p. 200.

- Hill, Reformation to Industrial Revolution, pp. 245–6.

- Marshall, East Indian Fortunes, pp. 255, 215.

- Cf. Saville, “Primitive Accumulation”, p. 265.

- Marx, Capital, vol. 1, p. 928.

- Marx, Capital, vol.1, p. 875.

- Semmel, Rise of Free Trade Imperialism, Chapter 4.

- Luxemburg, Accumulation of Capital, p. 272.

- Marx, Grundrisse, p. 327; italics mine.

- Serra, Short Treatise on the Wealth and Poverty of Nations, ed. Reinert.

- Poni, “Fashion as Flexible Production”.

- Hauser, La modernité du XVIe siècle, with the extract translated in Kitch, Capitalism and the Reformation, p. 72.

- Porter and Livesay, Merchants and Manufacturers.

- Chandler, Visible Hand.

- Stern, Gold and Iron, pp. 164, 181.

- Marx, Capital, vol.3, pp. 446–7.

- Marx, Grundrisse, p. 328.

- Linebaugh and Rediker, Many-headed Hydra, p. 149.

- Milne, Trade and Traders, p. 96.

- Mueller, Venetian Money Market.

- Preobrazhensky, New Economics, p. 85.

- Mehring, Absolutism and Revolution in Germany 1525–1848, pp. 1, 3.

- Preobrazhensky, New Economics, p. 87.

- Rubin, History of Economic Thought, esp. Chapters 1 and 2.

- Barber, Soviet Historians, p. 61, citing A. Malyshev.

- Lefebvre, “Some Observations”, p. 125.

- Roland Mousnier, Les XVIe et XVIIe siècles, fifth edn (Paris, 1967), p. 98.

- Dobb, Studies in the Development of Capitalism, p. 209.

- Thus in the late 17th century the great English mercantilist Charles D’Avenant saw foreign trade essentially as a source of capital accumulation, cf. his view “as money that circulates at home begets money to private men, so bullion circulating abroad begets bullion to a country”, cited Lipson, The Economic History of England, vol. 3: The Age of Mercantilism, sixth edn. (1956), p.85. Cf. Hilferding, “The Early Days of English Political Economy”, p.486: “money is here regarded in its constant process of circulation, where it only goes out in order to come back in, each time in increased amounts”, from his essay on Mun and the early mercantilists.

- Braudel, Wheels of Commerce, p. 321.

- Wolfgang von Stromer, Revue Historique, 1991 .

- Beier, “Engine”, p.161, citing Dobb, Studies, p. 145.

- Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution, p. 42.

- Goubert, Beauvais et le Beauvaisis de 1600 à 1730, p. ??.

- Veyssarat, Négociants et fabricants dans l’industrie cotonnière suisse, p. 205.

- Bythell, Sweated Trades, p. 13.

- Bythell, Sweated Trades, p. 249, citing Mendels, “Proto-industrialization”, Journal of Economic History, 32 (1972), p. 244.

- Berg, Age of Manufactures, first edn. pp.76–77; second edn., p. 65.

- Braudel, Wheels of Commerce, p. 273.

- Drescher, Econocide, p. 24.

- Drescher, Econocide, p. 25.

- Drescher, Econocide, p. 30.

- Hill, Reformation, p. 186.

- Nash, “Organization”, p. 124.

- Bergad, Cuban Rural Society, pp. 65, 167.

- Bergad, Cuban Rural Society, p. 173.

- Cited Inés Roldán de Montaud, “Baring Brothers and the Cuban Plantation Economy, 1814–1870”, p. 239.

- Foner, Business and Slavery, p. 191.

- Williams, Capitalism and Slavery, p. 210.

- Marx, Theories of Surplus-Value, pt. 2, pp. 302–3.

- Nash, “Organization”, p. 98.

- Nash, “Organization”, p. 103.

- Braudel, Wheels of Commerce, p. 279.

- Checkland, “Finance for the West Indies”, p. 467.

- Chayanov, Theory of Peasant Economy, p. 257.

- Marshall, East Indian Fortunes, p. 36.

- Fieldhouse, Merchant Capital and Economic Decolonization.

- Banaji, Brief History of Commercial Capitalism.

- Bharadwaj, Production Conditions, pp. 49, 64.

- Stewart, Jute and Empire, p. 44.

- Chen Han-Seng, Industrial Capital and Chinese Peasants, p. 23.

- Hossain, Company Weavers, p. 51.

- Marfaing, Evolution du commerce, pp. 177ff.

- Marx, Capital, vol.3, p. 344.

- Emmanuel, Unequal Exchange.

- Von Schmoller, The Mercantile System, p. 64.

- Marx, Capital, vol. 3, p. 920.

- Marx, Capital, vol. 3, p. 921.

- Marx, Capital, vol.1, p. 915.

- Rubin, History of Economic Thought, pp. 25–6.

- Brenner, Merchants and Revolution, p. 61.

- Brewer, Sinews of Power, p. 11.

- Brewer, Sinews of Power, p. 34.

- Hill, Century of Revolution, pp. 142, 143.

- Lublinskaya, French Absolutism: The Crucial Phase, Chapter 3.

- Mun, England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade (1628), cited Appleby, Economic Thought and Ideology in Seventeenth Century England, p. 40.

- Brewer, Sinews, p. 169.

- Brewer, Sinews, p. 168.

- Hinton, “Mercantile System in the Time of Thomas Mun”, p. 281.

- Hill, Reformation, p. 160.

- Cited Cole, French Mercantilism, p. 238.

- Israel, Dutch Primacy, p. 340.

- Brewer, Sinews, p. 119.

- Brewer, Sinews, p. 169.

- Gerschenkron, Europe in the Russian Mirror, pp. 79–80.

- Hilferding, “Das historische Problem”, Zeitschrift für Politik, 1 (1954), pp. 295–324, at 296.

- Hilferding, “Das historische Problem”, p. 296.

- Hilferding, “Das historische Problem”, p. 316.

- Sartre, Critique of Dialectical Reason, vol.1, p. 638.

- Sartre, Critique of Dialectical Reason, vol.1, p. 639.

- Sartre, Critique of Dialectical Reason, vol.1, p. 640.

- Wallerstein, Modern World System, p. 139.

- Especially Filtzer, Soviet Workers and Stalinist Industrialization (1986); Filtzer, The Hazards of Urban Life in Late Stalinist Russia (2010).

- Scott, Beyond the Urals, p. 61.

- Scott, Beyond the Urals, p. 54.

- Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers’ Control.

Primitive Accumulation and the State-Form: National Debt as an Apparatus of Capture

Gavin Walker

October 29, 2014

The moment has come to expose capital to the absence of reason, for which capital provides the fullest development: and this moment comes from capital itself, but it is no longer a moment of a “crisis” that can be solved in the course of the process. It is a different kind of moment to which we must give thought.

– J-L. Nancy 1

Commencement and Crisis 2

In a brief moment of his theoretical work, the great Japanese Marxist critic Tosaka Jun deployed a decisive and crucial phrase, a phrase that I believe concentrates within it the historical conjuncture we have been experiencing on a world-scale in the recent years of crisis: he calls this ultimate crystallization of politics “the facts of the streets” or “the facts on the streets” (gaitō no jijitsu). 3 I would like to excessively develop or overwrite – in other words translate – this phrase into a concept in the strong sense, to raise this seemingly marginal choice of words to the level of a principle, and to utilize this principle itself as a lever through which to force into existence a certain theoretical sequence. What Tosaka essentially reminds us of is the literal factuality (or more specifically, in Alain Badiou’s terms, the “veridicity”) of the streets, the “fact” that the streets themselves express the dense sociality that capital’s tendency towards the socialization of labor must necessarily-inevitably produce. In other words, what we have seen in the political energies that have been widely unleashed around the globe in the last year, is that the streets themselves recurrently-continuously testify or bear witness to their own “facts.” These “facts” are precisely the verso or underside of capital’s mapping on a world-scale. Or, to put it in another way, a way that I would like to develop here, “the facts of the streets” is the center of the volatile “absence of reason” or (im)possibility that is always “passing through” in between two polarities of theory that I will call capital’s logical topology and its historical cartography.