Archive

Can Democracy Reduce Inequality

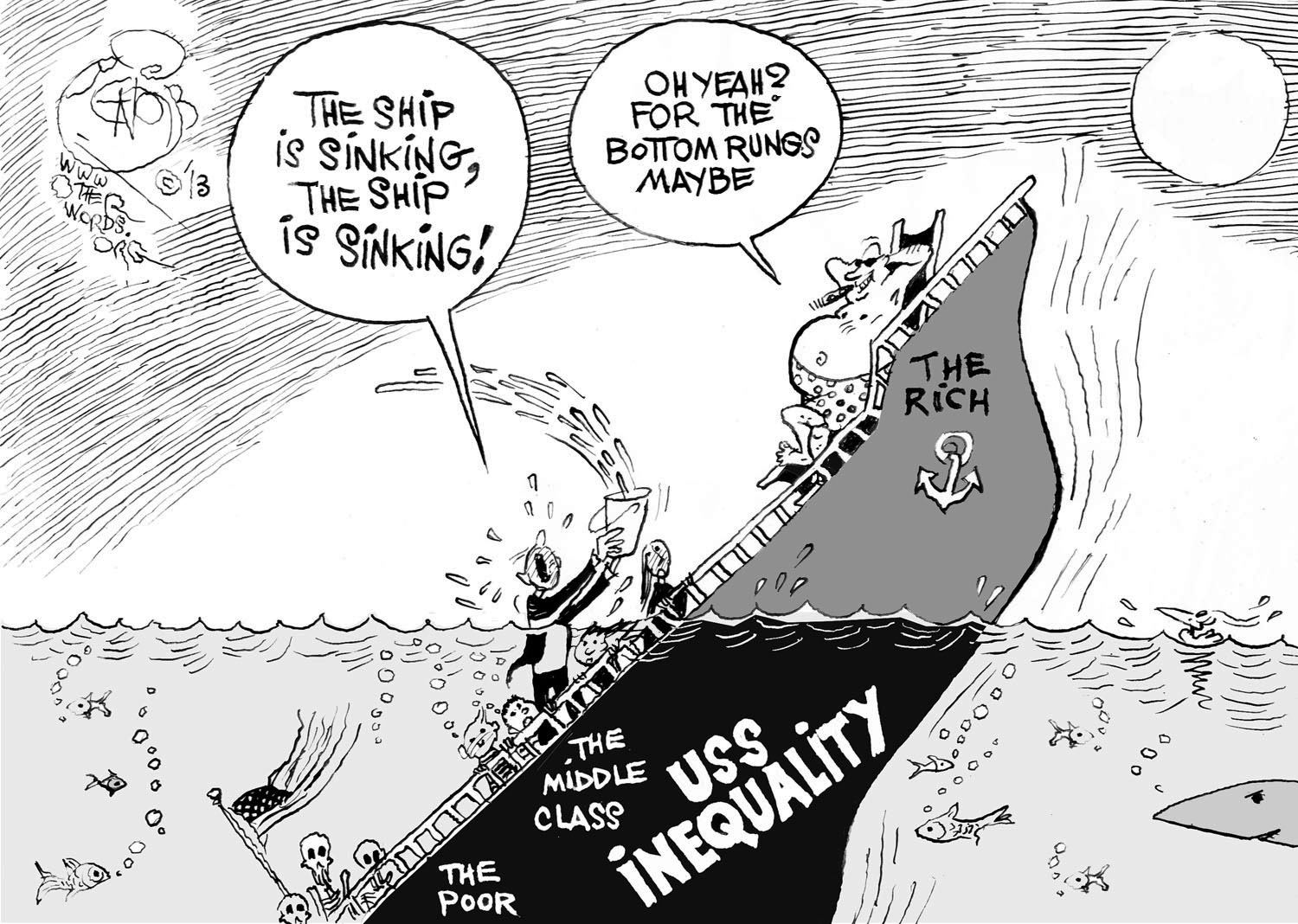

Despite two decades of social policies targeting poverty and inequality, Latin America remains one of the most economically unequal regions in the world. Recurrent protests motivated by economic grievances have been a regular reminder of this reality. The ongoing health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic has disproportionately harmed already vulnerable populations, undoing some of the progress made. At the same time, democracy has taken root in the region, and participation in elections is growing. Then why hasn’t democracy been more effective in resolving Latin America’s persistent inequality?

Research shows voters are not able to make their demands for greater redistribution heard, while governments are not implementing redistributive policies at the desired pace. Reasons include unequal political participation, institutional bias against redistribution, and vote buying. Until such impediments are removed, democracy’s impact on inequality will remain limited.

Between 2000 and 2018, income inequality in Latin America, as measured by the Gini index, gradually fell from 53.3 to 45.7. During the same period, government spending on social protection steadily increased by almost one percentage point of GDP. While these trends seem promising, inequality in Latin America remains high and social spending low by the standards of more advanced economies. For example, the thirty-six countries of the OECD reported a Gini index of only 33.2 in 2018. That is puzzling, given that at least on paper, Latin America is built on similar economic and political principles—market economies and representative democracies. One would expect that the democratic process, which by design is based on the egalitarian principle of “one person, one vote”, would lead to policies that reduce market inequalities. In other words, in a well-functioning democracy, inequality should to some extent be self-correcting. Why isn’t this happening to a greater degree in Latin America?

Weak Voter Demand for Policies that Lower Inequality

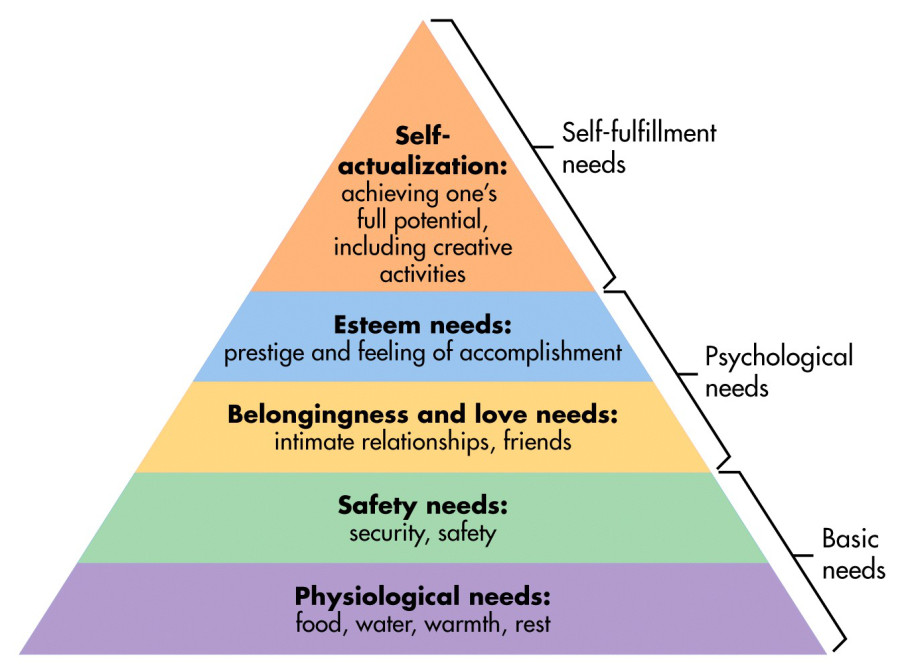

A first explanation is that voter demand for inequality-reducing policies remains relatively weak. Lack of voter pressure can be seen in limited and unequal political participation. Despite the widespread use of compulsory voting, voter turnout in the region has remained below 70% on average. More importantly, turnout is biased in a way that is detrimental to the poor, as voting is less common among the less educated and the less wealthy.

Even when they do vote, the less well-off are less informed, and thus less effective in choosing candidates that represent their economic interests. The poor are the greatest beneficiaries of basic public services, such as public education and health care. Unfortunately, voter demand for government investments in these public goods is tenuous, either due to low trust in the ability of public officials to spend public resources in these areas effectively, or due to a preference for immediate benefits such as cash transfers, at the expense of longer-term benefits such as high-quality education and public safety.

Weak Supply of Policies Designed to Reduce Inequality

A second explanation is that the policymaking process may fail to internalize popular demand for redistribution. In some cases, this occurs because political institutions can be manipulated by incumbents to retain power, for example through legislative malapportionment. Others argue that elements of the elite gain access to and remain in power using campaign donations from narrow interest groups, obviating the need to rely on broad popular support.

More recent research has shown that vote buying by political candidates, a prevalent phenomenon in many Latin American democracies, subverts the normal functioning of the budget process. Voters targeted with vote buying prior to an election may receive no government benefits after the election. As poorer voters are more susceptible to vote buying, they are often left unrepresented in the subsequent negotiations over the budget. Thus, vote buying crowds out redistributive spending that could reduce inequality.

Stronger Democracies Better Alleviate Inequality

In a chapter of the recent IDB report entitled The Inequality Crisis I present new data patterns that support the idea that the strength of democracy matters for the alleviation of inequality. I use the Economist Intelligence Unit democracy index to rank democratic quality along five dimensions. Among Latin American countries, stronger democracies provide more redistributive spending. At one end of the spectrum, Nicaragua spends less than 1% of GDP on social protection, compared to almost 7% in Uruguay, at the other end of the spectrum. Interestingly, stronger democracies are also characterized by higher voter turnout and fewer protests. This suggests that voting, rather than protesting, is a catalyst for government redistribution. Protests appear to be a symptom of unmet economic expectations.

Some development institutions, such as the UNDP, have suggested that inequality may be one of democracy’s greatest weaknesses. As the less well-off are economically marginalized, they become more disengaged with the democratic process. However, a weaker democracy may also fail to alleviate inequality. Overcoming this vicious circle remains a challenge for Latin America’s young democracies. Political and civic leaders in the region should renew their commitment to strengthening democratic institutions, chief among them free elections, civic liberties, and independent media. Over time, better-functioning democracies should improve economic equity. Democracy can certainly reduce inequality, as long as it functions as intended.

Income Inequality and Citizenship: Quantifying the Link

Our level of income is unarguably dependent on where we live in the world. But evidencing this is tricky. This Posting presents a model that explains global income variability using one variable only – where you live. The results suggest that we might want to reassess how we think about both economic migration and global inequality of opportunity.

It is as obvious as it is well known that the world is unequal in terms of individuals’ incomes (e.g. Mohammed 2015). But it is unequal in a very particular way – when split into ‘inequality within countries’ and ‘inequality between countries’, the latter accounts for by far the biggest gap.

Inequality within countries measures, for instance, gaps between poor and rich Americans or between poor and rich Chinese. For simplicity, let’s call it ‘class’ inequality. But there is also another equally obvious inequality – that between rich and poor nations. More specifically, this inequality is measured as the gap between the ‘representative’ or ‘average’ individuals of any two countries, be they Morocco and Spain or Mexico and the US. For simplicity, let’s call this ‘locational’ inequality.

Inequality, as it is commonly understood in today’s world, is such that whatever measure we choose, the lion’s share of global inequality is ‘explained’ by the differences in mean incomes between countries.

This was not always the case. Although our data for the past are far more tentative than our data for today’s global income distribution, we can still state with little doubt that the dominant type of equality in the 19th century was that within countries (see Milanovic 2011).

Citizenship Premiums and Penalties

If income differences between countries are large then your income will significantly depend on where you live, or even on where you were born (97% of the world’s population remain in the countries where they were born). This is what I call a ‘citizenship premium’ (or a ‘citizenship penalty’) – a ‘rent’ that a person receives if he or she happens to be born in a rich country, or, if we use the terminology introduced by John Roemer, an ‘exogenous circumstance’ which is independent from any one individual’s effort and episodic luck (Roemer 2000).

How big is citizenship rent, how does it vary with one’s position in the income distribution, and what does it imply for global inequality of opportunity and migration?

Estimating Citizenship Rent

I estimate citizenship rent by using data collected from household surveys conducted in 118 countries in and around the year 2008 (Milanovic 2015). For each country, I have micro-level (household) data ordered into 100 percentiles, with individuals ranked by their household per capita income. This gives 11,800 country/percentiles with ‘representative’ per capita incomes expressed in dollars of equal purchasing parity, making incomes across countries comparable.

I ‘explain’ these incomes using only one variable – the country where individuals live. Of course, people living in the US will tend to have higher incomes at any given percentile of the distribution than people living in poor countries in, for instance, Africa. But how will it look for the world as a whole? In a least-square dummy variable regression, I use Congo (the poorest county in the world) as the ‘omitted country’ so that I can express the citizenship premium in every other country in terms of the income gain compared to Congo. The premium for the US is 355%, it is 329% for Sweden and 164% for Brazil. But for Yemen, another very poor country, it’s 32%.

According to this regression, we can explain more than two-thirds of the variability in incomes across country/percentiles by only one variable – the country where people live. This estimation shows that, as we thought, a lot of our income depends on where we live.

Citizenship Rent across the Distribution

But this is only an average premium that compares countries. Does citizenship rent vary along the entire income distribution? If I were to take into consideration only people belonging to the lowest part of the income distribution in each country, would the premium still be the same?

Intuition may help here. Suppose that I focus only on the incomes of the lowest decile (with rich countries more equal than poor countries). Then the gap between rich and poor countries should be greater for the very poor people than for the average individual. And this is indeed what we find – Sweden’s citizenship premium compared to Congo is now 367% versus 329% on average. But Brazil’s is 133% versus 164%. The situation at the top is exactly the opposite – Sweden’s advantaged position at the 90th percentile of the income distribution is ‘only’ 286%, but Brazil’s becomes 188%.

Implications for Migration

The existence of the citizenship premium has obvious implications for migration: people from poor countries will have the opportunity to double or triple their real incomes by moving to a rich country.

But the fact that the premium varies as a function of one’s position in the income distribution carries additional implications. If I consider moving to one of two countries that have the same average income, my decision on where to migrate – based on economic criteria alone – will also be influenced by my expectations regarding where I may end up in the recipient county’s income distribution. My decision will thus be influenced by the extent to which the recipient country’s income distribution is unequal.

Suppose that Sweden and the US have the same mean income. If I expect to end up in the bottom part of a recipient country’s distribution, then I should migrate to Sweden. The poor people in Sweden are better off compared to the mean, and the citizenship premium, evaluated at lower parts of distribution, is greater. The opposite conclusion follows if I expect to end up in the upper part of the recipient country’s distribution – I should migrate to the US.

This last result has unpleasant implications for rich countries with greater ‘in-country’ equality. More equal rich countries will tend to attract lower-skilled migrants who generally expect to be placed in the bottom part of the recipient country’s distribution. Developing a national welfare state would have the perverse effect of attracting migrants who can contribute less.

Even in this rough sketch, we also have to consider the levels of social mobility in recipient countries because more unequal countries with strong social mobility will, everything else being the same, tend to appeal to more skilled migrants.

Global Inequality of Opportunity

The mere existence of a large citizenship premium implies that there is no such a thing as global equality of opportunity because a lot of our income depends on the accident of birth.

So should we strive for global equality of opportunity or not? It is a political philosophy question that philosophers have thought much more about than economists. Some, following John Rawls in The Law of Peoples, believe that this is not an issue and that every argument for global equality of opportunity would conflict with the right of national self-determination. But other political philosophers like Thomas Pogge believe that in an interdependent world, the dominant role of chance in people’s life is not to be accepted lightly (Pogge 2008). I am not proposing a solution to this issue, yet, I believe that economists should not shy away from addressing it.1

As gaps between nations diminish, mostly thanks to the high growth rates of Asian countries, the citizenship rent will tend to reduce. But there is such a huge gap today that even a century of much higher growth in poor countries (in comparison to rich countries) will not eradicate citizenship rent.

However, it will reduce. As it does, it will also reduce overall global inequality. This might then lead us to a world not dissimilar to the mid-19th century, in which class is again more important for one’s global income position than location.

Do I hear the distant sound of Marx?

References

Milanovic, B (2011), The haves and the have-nots: a short and idiosyncratic history of global inequality, New York: Basic Books.

Milanovic, B (2015), “Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of Our Income Is Determined By Where We Live?”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 97(2): 452-460.

Mohammed, A (2015), “Deepening income inequality”, World Economic Forum report.

Pogge, T (2008), World Poverty and Human Rights, Polity Press.

Rawls, J (2001), The Law of Peoples, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J (2000), Equality of Opportunity, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shachar, A (2009), The Birthright Lottery, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Footnote

1 Legal scientists such as Ayalet Shachar have written about addressing global inequality from a legal standpoint, proposing a much more flexible and open definition of citizenship (see Shachar 2009).

Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession

Since 1988, rapid growth in Asia has lifted billions out of poverty. Incomes at the very top of the world income distribution have also grown rapidly, whereas median incomes in rich countries have grown much more slowly. This posting asks whether these developments, while reducing global income inequality overall, might undermine democracy in rich countries.

The period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Great Recession saw probably the most profound reshuffle of individual incomes on the global scale since the Industrial Revolution. This was driven by high growth rates of populous and formerly poor or very poor countries like China, Indonesia, and India; and, on the other hand, by the stagnation or decline of incomes in sub-Saharan Africa and post-communist countries as well as among poorer segments of the population in rich countries.

Anand and Segal (2008) offer a detailed review of the work on global income inequality. In Lakner and Milanovic (2013), we address some of the limitations of these earlier studies and present new results from detailed work on household survey data from about 120 countries over the period 1988–2008. Each country’s distribution is divided into ten deciles (each decile consists of 10% of the national population) according to their per capita disposable income (or consumption). In order to make incomes comparable across countries and time, they are corrected both for domestic inflation and differences in price levels between countries. It is then possible to observe not only how the position of different countries changes over time – as we usually do – but also how the position of various deciles within each country changes. For example, Japan’s top decile remained at the 99th (2nd highest from the top) world percentile, but Japan’s median decile dropped from the 91st to the 88th global percentile. Or, to take another example, the top Chinese urban decile moved from being in the 68th global percentile in 1988 to being in the 83rd global percentile in 2008, thus leapfrogging in the process some 15% of the world population – equivalent to almost a billion people.

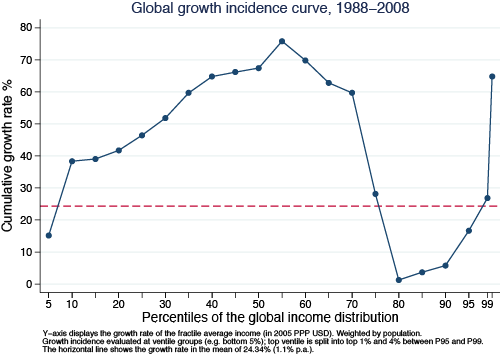

When we line up all individuals in the world, from the poorest to the richest (going from left to right on the horizontal axis in Figure 1), and display on the vertical axis the percentage increase in the real income of the equivalent group over the period 1988–2008, we generate a global growth incidence curve – the first of its kind ever, because such data at the global level were not available before. The curve has an unusual supine S shape, indicating that the largest gains were realised by the groups around the global median (50th percentile) and among the global top 1%. But after the global median, the gains rapidly decrease, becoming almost negligible around the 85th–90th global percentiles and then shooting up for the global top 1%. As a result, growth in the income of the top ventile (top 5%) accounted for 44% of the increase in global income between 1988 and 2008.

Fortunes of income deciles in different countries over time

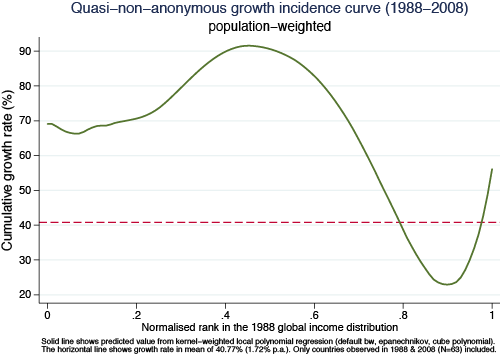

The curve in Figure 1 is drawn using a simple comparison of real income levels at given percentiles of the global income distribution in 1988 and 2008. It is ‘anonymous’ because it does not tell us what happened to the actual people who were at given global income percentiles in the initial year, 1988. In fact, the regional composition of the different global income groups changed radically over time because growth was uneven across regions. A ‘quasi non-anonymous’ growth incidence curve in Figure 2 adjusts for this – the growth rates are calculated for all individual country/deciles at the positions they held in the initial year (1988). The growth rate on the vertical axis (calculated from a non-parametric fit) thus shows how the country/deciles that were poor, middle-class, rich, etc. in 1988 performed over the next 20 years. The supine S shape still remains, although it is now slightly less dramatic.

People around the median almost doubled their real incomes. Not surprisingly, 9 out of 10 such ‘winners’ were from the ‘resurgent Asia’. For example, a person around the middle of the Chinese urban income distribution saw his or her 1988 real income multiplied by a factor of almost 3; someone in the middle of the Indonesian or Thai income distribution by a factor of 2, Indian by a factor of 1.4, etc.

It is perhaps less expected that people who gained the least were almost entirely from the ‘mature economies’ – OECD members that include also a number of former communist countries. But even when the latter are excluded, the overwhelming majority in that group of ‘losers’ are from the ‘old, conventional’ rich world. But not just anyone from the rich world. Rather, the ‘losers’ were predominantly the people who in their countries belong to the lower halves of national income distributions. Those around the median of the German income distribution have gained only 7% in real terms over 20 years; those in the US, 26%. Those in Japan lost out in real terms.

The particular supine S-shaped growth incidence curve (Figure 1) does not allow us to immediately tell whether global inequality might have gone up or down because the gains around the median (which tend to reduce inequality) may be offset by the gains of the global top 1% (which tend to increase inequality). On balance, however, it turns out that the first element dominates, and that global inequality – as measured by most conventional indicators – went down. The global Gini coefficient fell by almost 2 Gini points (from 72.2 to 70.5) during the past 20 years of globalisation. Was it then all for the better?

Probably yes, but not so simply. The striking association of large gains around the median of the global income distribution – received mostly by the Asian populations – and the stagnation of incomes among the poor or lower middle classes in rich countries, naturally opens the question of whether the two are associated. Does the growth of China and India take place on the back of the middle class in rich countries? There are many studies that, for particular types of workers, discuss the substitutability between rich countries’ low-skilled labour and Asian labour embodied in traded goods and services or outsourcing. Global income data do not allow us to establish or reject the causality. But they are quite suggestive that the two phenomena may be related.

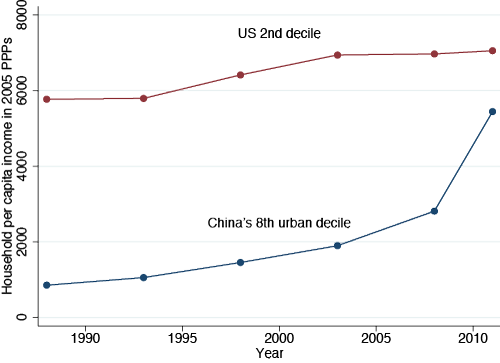

A dramatic way to see the change brought by globalisation is to compare the evolution over time of the 2nd US income decile with (say) the Chinese urban 8th decile (Figure 3). Indeed we are comparing relatively poor people in the US with relatively rich people in China, but given the income differences between the two countries, and that the two groups may be thought to be in some kind of global competition, the comparison makes sense. Here we extend the analysis to 2011, using more recent and preliminary data. While the real income of the US 2nd decile has increased by some 20% in a quarter century, the income of China’s 8th decile has been multiplied by a factor of 6.5. The absolute income gap, still significant five years ago, before the onset of the Great Recession, has narrowed substantially.

Political Implications

And even if the causality cannot be established because of many technical difficulties and an inability to define credible counterfactuals, the association between the two cannot pass unnoticed. What, then, are its implications? First, will the bottom incomes of the rich countries continue to stagnate as the rest of China, or later Indonesia, Nigeria, India, etc. follow the upward movement of Chinese workers through the ranks of the global income distribution? Does this imply that the developments that are indeed profoundly positive from the global point of view may prove to be destabilising for individual rich countries?

Second, if we take a simplistic, but effective, view that democracy is correlated with a large and vibrant middle class, its continued hollowing-out in the rich world would, combined with growth of incomes at the top, imply a movement away from democracy and towards forms of plutocracy. Could then the developing countries, with their rising middle classes, become more democratic and the US, with its shrinking middle class, less?

Third, and probably the most difficult: What would such movements, if they continue for a couple of decades, imply for global stability? The formation of a global middle class, or the already perceptible ‘homogenisation’ of the global top 1%, regardless of their nationality, may be both deemed good for world stability and interdependency, and socially bad for individual countries as the rich get ‘delinked’ from their fellow citizens.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, the movements that we witness do not only lead to an economic rebalancing of the East and West – in which both may end up with global output shares close to what they had before the Industrial Revolution – but to a contradiction between the current world order, where political power is concentrated at the level of the nation-state, and the economic forces of globalization which have gone far beyond it.

References

Anand, Sudhir and Paul Segal (2008), “What Do We Know about Global Income Inequality?”, Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1): 57–94.

Lakner, Christoph and Branko Milanovic (2013), “Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession”, World Bank Working Paper No. 6719, December.

Redistribution, Inequality, and Sustainable Growth: Reconsidering the Evidence

Inequality has the potential to undermine growth. However, greater redistribution requires higher tax rates, which reduce incentives to work and save. Moreover, the evidence that inequality is bad for growth might simply reflect the fact that more unequal societies choose to redistribute more, and those efforts are antithetical to growth. This column presents evidence from a new dataset on pre- and post-tax inequality. The authors find that income equality is protective of growth, and that redistributive transfers on average have little if any direct adverse impact on growth.

Rising income inequality looms high on the global policy agenda, reflecting not only fears of its pernicious social and political effects (including questions about the consistency of extreme inequality with democratic governance), but also its economic implications. While positive incentives are surely needed to reward work and innovation, excessive inequality is likely to undercut growth – for example by undermining access to health and education, causing investment-reducing political and economic instability, and thwarting the social consensus required to adjust in the face of major shocks.

Understandably, economists have been trying to understand better the links between rising inequality and the fragility of economic growth. Recent narratives include how inequality intensified the leverage and financial cycle, sowing the seeds of crisis (Rajan 2010), or how political-economy factors – especially the influence of the rich – allowed financial excess to balloon ahead of the crisis (Stiglitz 2012).

But what is the role of policy – and in particular fiscal redistribution – in bringing about greater equality? Conventional wisdom suggests that redistribution would in itself be bad for growth, but by reducing inequality, it might conceivably help growth. Looking at past experience, we find scant evidence that typical efforts to redistribute have on average had an adverse effect on growth. Moreover, faster and more durable growth seems to have followed the associated reduction in inequality.

Disentangling the Effects of Inequality and Redistribution on Growth

In earlier work (Berg and Ostry 2011), we documented a robust medium-run relationship between equality and the sustainability of growth. We did not, however, have much to say on whether this relationship justifies efforts to redistribute.

Indeed, many argue that redistribution undermines growth, and even that efforts to redistribute to address high inequality are the source of the correlation between inequality and low growth. If this is right, then taxes and transfers may be precisely the wrong remedy – a cure that may be worse than the disease itself.

The literature on this score remains controversial. A number of papers (e.g. Benabou 2000) point out that some policies that are redistributive – e.g. public investments in infrastructure, spending on health and education, and social insurance provision – may be both pro-growth and pro-equality. Others are more supportive of a fundamental tradeoff between redistribution and growth, as argued by Okun (1975) when he referred to the efficiency ‘leaks’ that come with efforts to reduce inequality.

In a new paper (Ostry et al. 2014), we ask what the historical data say about the relationship between inequality, redistribution, and growth. In particular, what is the evidence about the macroeconomic effects of redistributive policies – both directly on growth, and indirectly as they reduce inequality, which in turn affects growth?

To disentangle the channels, we make use of a new cross-country dataset that carefully distinguishes net (post-tax and transfers) inequality from market (pre-tax and transfers) inequality, and allows us to calculate redistributive transfers for a large number of countries over time – covering both advanced and developing countries. We analyse the behaviour of average growth during five-year periods, as well as the sustainability and duration of growth.

Our key questions are empirical. How big is the ‘big tradeoff’? How does the direct (in Okun’s view negative) effect of redistribution compare to its indirect and apparently positive effect through reduced inequality?

Some Striking Results on the Links between Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth

- First, we continue to find that inequality is a robust and powerful determinant both of the pace of medium-term growth and of the duration of growth spells, even controlling for the size of redistributive transfers.

Thus, it would still be a mistake to focus on growth and let inequality take care of itself, if only because the resulting growth may be low and unsustainable. Inequality and unsustainable growth may be two sides of the same coin.

- Second, there is remarkably little evidence in the historical data used in our paper of adverse effects of fiscal redistribution on growth.

The average redistribution, and the associated reduction in inequality, seem to be robustly associated with higher and more durable growth. We find some mixed signs that very large redistributions may have direct negative effects on growth duration, such that the overall effect – including the positive effect on growth through lower inequality – is roughly growth-neutral.

Caveats

These findings may suggest that countries that have carried out redistributive policies have actually designed those policies in a reasonably efficient way. However, it does not mean of course that countries wishing to enhance the redistributive role of fiscal policy should not pay attention to efficiency considerations. This is especially important for countries with weak governance and administrative capacity, where developing tax and spending instruments that can allow governments to undertake redistribution efficiently are of the essence. A forthcoming paper by the IMF will delve into these fiscal issues.

Of course, we should also be cautious about drawing definitive policy implications from cross-country regression analysis alone. We know from history and first principles that after some point redistribution will be destructive to growth, and that beyond some point extreme equality also cannot be conducive to growth. Causality is difficult to establish with full confidence, and we also know that different sorts of policies are likely to have different effects in different countries at different times.

Bottom line

The conclusion that emerges from the historical macroeconomic data used in this paper is that, on average across countries and over time, the things that governments have typically done to redistribute do not seem to have led to bad growth outcomes. Quite apart from ethical, political, or broader social considerations, the resulting equality seems to have helped support faster and more durable growth.

To put it simply, we find little evidence of a ‘big tradeoff’ between redistribution and growth. Inaction in the face of high inequality thus seems unlikely to be warranted in many cases.

References

Benabou, R (2000), “Unequal Societies: Income Distribution and the Social Contract”, The American Economic Review, 90(1): 96–129.

Berg, A, J D Ostry, and J Zettelmeyer (2012), “What Makes Growth Sustained?”, Journal of Development Economics, 98(2): 149–166.

Berg, A and J D Ostry (2011), “Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?”, IMF Staff Discussion Note 11/08.

Okun, A M (1975), Equality and Efficiency: the Big Trade-Off, Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Ostry, J D, A Berg, and C G Tsangarides (2014), “Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth”, IMF Staff Discussion Note 14/02.

Rajan, R (2010), Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stiglitz, J (2012), The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, W W Norton & Company.

Can Democracy Help with Inequality?

Inequality is currently a prominent topic of debate in Western democracies. In democratic countries, we might expect rising inequality to be partially offset by an increase in political support for redistribution. This column argues that the relationship between democracy, redistribution, and inequality is more complicated than that. Elites in newly democratized countries may hold on to power in other ways, the liberalization of occupational choice may increase inequality among previously excluded groups, and the middle classes may redistribute income away from the poor as well as the rich.

There is a great deal of concern at the moment about the consequences of rising levels of inequality in North America and Western Europe. Will this lead to an oligarchisation of the political system, and imperil political and social stability? Many find such dynamics puzzling given that it is happening in democratic countries. In democratic societies, there ought to be political mechanisms that can inhibit or reverse large rises in inequality, most likely through the fiscal system. Indeed, one of the most central models in political economy, due originally to Meltzer and Richard (1981), suggests that high inequality in a democracy should lead the politically powerful (in their model the voter at the median of the income distribution) to vote for higher levels of taxes and redistribution, which would partially offset rising inequality.

But before asking about what happens in a democracy, we could start with some even more fundamental questions. Is it correct factually that democracies redistribute more income than dictatorships? When a country becomes democratic, does this tend to increase redistribution and reduce inequality? The existing scholarship on these questions, though vast, is quite contradictory. Historical studies, such as Acemoglu and Robinson (2000) and Lindert (2004), tend to suggest that democratization increases redistribution and reduces inequality. Using cross-national data, Gil et al. (2004) find no correlation between democracy as measured by the Polity score and any government spending or policy outcome. The evidence on the impact of democracy on inequality is similarly puzzling. An early survey by Sirowy and Inkeles (1990) concludes, “the existing evidence suggests that the level of political democracy as measured at one point in time tends not to be widely associated with lower levels of income inequality” (p. 151), though Rodrik (1999) finds that both the Freedom House and Polity III measures of democracy were positively correlated with average real wages in manufacturing and the share of wages in national income (in specifications that also control for productivity, GDP per capita, and a price index).

In a recent working paper (Acemoglu et al. 2013), we revisit these questions both theoretically and empirically.

Theoretical Nuances

Theoretically, we point out why the relationship between democracy, redistribution, and inequality may be more complex than the discussion above might suggest. First, democracy may be ‘captured’ or ‘constrained’. In particular, even though democracy clearly changes the distribution of de jure power in society, policy outcomes and inequality depend not just on the de jure but also the de facto distribution of power. Acemoglu and Robinson (2008) argue that, under certain circumstances, elites who see their de jure power eroded by democratization may sufficiently increase their investments in de facto power (e.g. via control of local law enforcement, mobilization of non-state armed actors, lobbying, and other means of capturing the party system) in order to continue to control the political process. If so, we would not see much impact of democratization on redistribution and inequality. Similarly, democracy may be constrained by other de jure institutions such as constitutions, conservative political parties, and judiciaries, or by de facto threats of coups, capital flight, or widespread tax evasion by the elite.

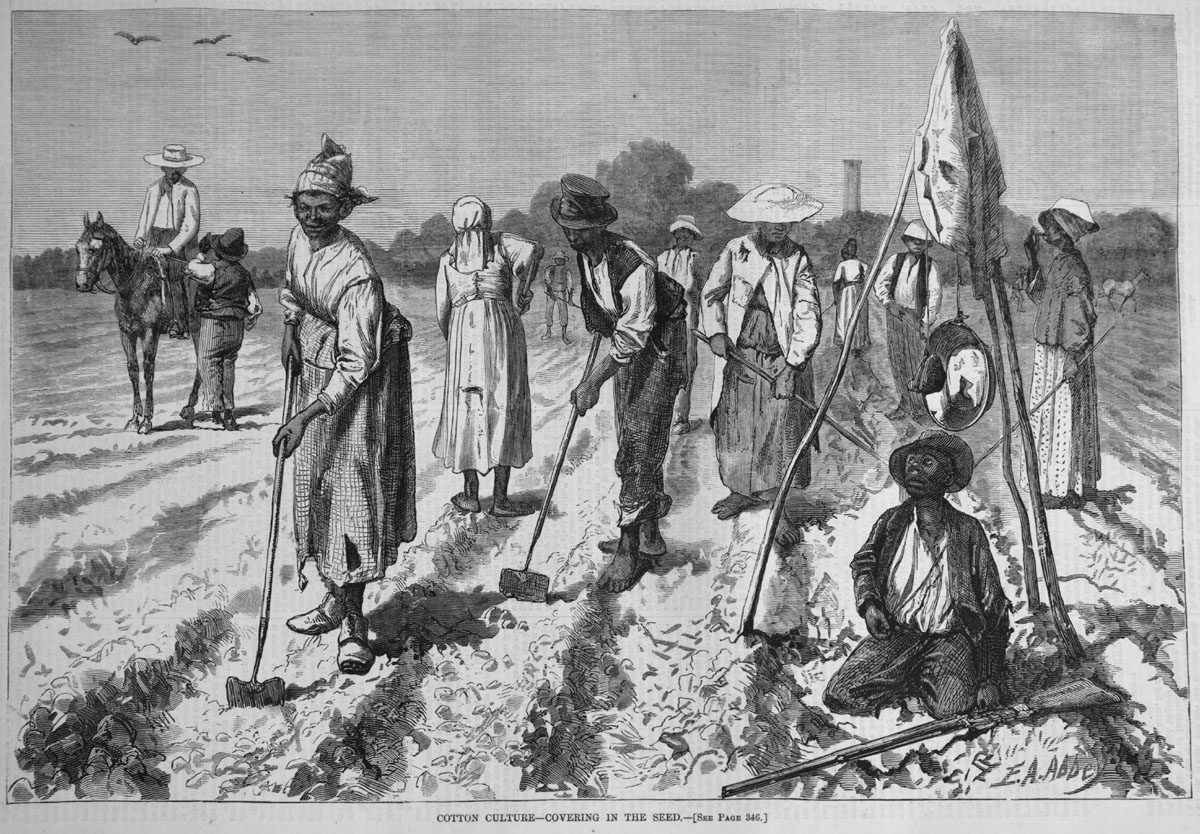

Democratization can also result in ‘inequality-increasing market opportunities’. Non-democracy may exclude a large fraction of the population from productive occupations (e.g. skilled occupations) and entrepreneurship (including lucrative contracts), as in Apartheid South Africa or the former Soviet Union. To the extent that there is significant heterogeneity within this population, the freedom to take part in economic activities on a more level playing field with the previous elite may actually increase inequality within the excluded or repressed group, and consequently the entire society.

Finally, consistent with Stigler’s ‘Director’s Law’ (1970), democracy may transfer political power to the middle class, rather than the poor. If so, redistribution may increase and inequality may be curtailed only if the middle class is in favour of such redistribution.

But what are the basic robust facts, and do they support any of these mechanisms?

Empirical Evidence

Cross-sectional (cross-national) regressions, or regressions that do not control for country fixed effects, will be heavily confounded with other factors likely to be simultaneously correlated with democracy and inequality. In our work we therefore focus on a consistent panel of countries, and investigate whether countries that become democratic redistribute more and reduce inequality relative to others. We also focus on a consistent definition of democratization based on Freedom House and Polity indices, building on the work by Papaioannou and Siourounis (2008).

One of the problems of these indices is the significant measurement error, which creates spurious movements in democracy. To minimize the influence of such measurement error, we create a dichotomous measure of democracy using information from both the Freedom House and Polity data sets, as well as other codings of democracies, to resolve ambiguous cases. This leads to a binary measure of democracy for 184 countries annually from 1960 (or post-1960 year of independence) to 2010. We also pay special attention to modeling the dynamics of our outcomes of interest – taxes as a percentage of GDP, and various measures of structural change and inequality.

Our empirical investigation uncovers a number of interesting patterns. First, we find a robust and quantitatively large effect of democracy on tax revenues as a percentage of GDP (and also on total government revenues as a percentage of GDP). The long-run effect of democracy in our preferred specification is about a 16% increase in tax revenues as a fraction of GDP. This pattern is robust to various different econometric techniques and to the inclusion of other potential determinants of taxes, such as unrest, war, and education.

Second, we find an effect of democracy on secondary school enrolment and the extent of structural transformation (e.g. an impact on the nonagricultural shares of employment and output).

Third, however, we find a much more limited effect of democracy on inequality. Even though some measures and some specifications indicate that inequality declines after democratization, there is no robust pattern in the data (certainly nothing comparable to the results on taxes and government revenue). This may reflect the poorer quality of inequality data. But we also suspect it may be related to the more complex, nuanced theoretical relationships between democracy and inequality pointed out above.

Fourth, we investigate whether there are heterogeneous effects of democracy on taxes and inequality consistent with these more nuanced theoretical relationships. The evidence here points to an inequality-increasing impact of democracy in societies with a high degree of land inequality, which we interpret as evidence of (partial) capture of democratic decision-making by landed elites. We also find that inequality increases following a democratisation in relatively nonagricultural societies, and also when the extent of disequalising economic activities is greater in the global economy as measured by US top income shares (though this effect is less robust). These correlations are consistent with the inequality-inducing effects of access to market opportunities created by democracy. We also find that democracy tends to increase inequality and taxation when the middle class are relatively richer compared to the rich and poor. These correlations are consistent with Director’s Law, which suggests that democracy allows the middle class to redistribute from both the rich and the poor to itself.

Conclusions

These results do suggest that some of our basic intuitions about democracy are right – democracy does represent a real shift in political power away from elites that has first-order consequences for redistribution and government policy. But the impact of democracy on inequality may be more limited than one might have expected.

This might be because recent increases in inequality are ‘market-induced’ in the sense of being caused by technological change. But at the same time, our work also suggests reasons why democracy may not counteract inequality. Most importantly, this may be because, as in the Director’s Law, the middle classes use democracy to redistribute to themselves. Nevertheless, since the increase in inequality in the US has been associated with a significant surge in the share of income accruing to the very rich, compared to both the middle class and the poor, Director’s Law-type mechanisms seem unlikely to be able to explain why policy has not changed to counteract this. Clearly other political mechanisms must be at work, the nature of which requires a great deal of research.

References

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson (2000), “Why Did the West Extend the Franchise?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115: 1167–1199.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson (2008), “Persistence of Power, Elites and Institutions”, The American Economic Review, 98: 267–291.

Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A Robinson (2013), “Democracy, Redistribution and Inequality”, NBER Working Paper 19746.

Gil, Ricard, Casey B Mulligan, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin (2004), “Do Democracies have different Public Policies than Nondemocracies?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18: 51–74.

Lindert, Peter H (2004), Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth since the Eighteenth Century, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Meltzer, Allan M and Scott F Richard (1981), “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government”, Journal of Political Economy, 89: 914–927.

Papaioannou, Elias and Gregorios Siourounis (2008), “Democratisation and Growth”, Economic Journal, 118(532): 1520–1551.

Rodrik, Dani (1999), “Democracies Pay Higher Wages”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114: 707–738.

Sirowy, Larry and Alex Inkeles (1990), “The Effects of Democracy on Economic Growth and Inequality: A Review”, Studies in Comparative International Development, 25: 126–157.

Stigler, George J (1970), “Director’s Law of public income redistribution”, Journal of Law and Economics, 13: 1–10.

Accumulation, Capitalism and Politics: Towards an Integrated Approach

This article aims to regenerate analysis of how accumulation relates to politics by underlining that one cannot be theorized without the other. After recalling how initial Marxist and institutionalist problematics implied the need to grasp the relationship between these two terms, we set out to show how coupling regulation theory with field theory enables empirical analysis to reveal the political structuring of accumulation.

Introduction

In an article published in 2007, Robert Boyer noted a renewed interest in the social sciences – sociology, political science and political economy, in particular – for the concept of capitalism. Editorial news lends credence to this finding 1 , in France and beyond. Somewhat surprisingly, however, this renewed interest does not translate into renewed attention to the process that underlies the uniqueness of capitalist economic organization: the accumulation of capital, that is to say the perpetual transformation profits into new productive forces to generate new profits. An effort of definition is therefore necessary. Economic system, capitalism produces and offers goods and services, but for a particular purpose, to make profits 2. According to Ellen Meiksins Wood (2019), this phenomenon is due to the fact that, in this system, the agents (the workers as well as the capitalists themselves) are prey to what Karl Marx calls “the silent constraint of economic relations” – the the former are forced to sell their labor power for a wage, the latter to use it to acquire their means of production and sell their products. This dependence means that “the mechanisms of competition and profit maximization become fundamental rules of existence” ( ibid., p. 9). The quest for labor productivity, which is based in particular on the acquisition of new technical means, is, in this system, a condition of economic survival for entrepreneurs. So much so that “the first objective of the [capitalist] system is the production of capital and its natural growth” ( id. ). From this perspective, the study of capitalism is that of the accumulation of capital, of its origins and of its multiple socio-economic and political effects.

The call for papers, from which the articles in this file are taken, therefore proposed to put the question of capital accumulation back on the job, but from a specific angle. Far from claiming to exhaust the question, this introductory text will focus more particularly on the political structures – understanding the political balance of power – inseparable from the “mechanism of the capitalist economy” (Petit, 1969, p. 9). This insight will evoke an old question for those who frequented the benches of universities before the decline of academic Marxism. It will be different for the generations that followed. Be that as it may, and without denying – quite the contrary – the contributions of classical writings,

By returning to classical political economy, we will first propose to grasp accumulation as an intrinsically political economic process. The latter is indeed based on conflicts – conflicts of powers, beliefs and values 3 –, whose permanence it maintains (Hay & Smith, 2018). We will thus observe that accumulation is political through its “structuring structures” (Bourdieu, 1980), i.e. the power relations that it induces, for example the reproduction of the asymmetry of positions between a worker and a capitalist, but also by his “structured structures”, the relations of forces which are at the origin of this one and found it, like private property or primitive accumulation. Through the commentary on the articles in the dossier, the sections that follow propose a diagram for analyzing the political structures of accumulation, while illustrating it with the help of empirical examples drawn in particular from the texts brought together here. In a second step, we will thus take advantage of the institutionalist tradition (in particular of certain achievements of the school of regulation but also of certain sociological currents) to draw attention to the institutions which organize and support accumulation and to the orders in which the forces competing for their production oppose each other. In a third step, relying on the structuralist tradition (in particular on the economic anthropology of Pierre Bourdieu), we will deepen this analytical scheme articulated around three concepts – “institutions, fields and political work” – in order to empirically decipher the processes that support the accumulation. Thus, echoing certain authors of regulation theory (TR),

Putting the question of accumulation back on the table – precisely that of its political structures – is not just an intellectual issue. By remaining particularly discreet on this subject in Europe and the United States 4, social sciences participate in the naturalization of the capitalist economy, its mechanisms and its effects. This is the case, in France, with the abundant literature on the sociology of markets which reduces economic activity to markets in order to study the mechanisms for adjusting supply and demand (Hay & Smith, 2018). The same goes for Anglo-Saxon literature, also abundant on the varieties of capitalism, and which, drawing on the institutionalist tradition, captures national economies through their firms and the way in which they coordinate (Roger , 2018). In one case as in the other, no word is said on the way in which the new productive forces appear, any more than on the relations of force which organize them and which they produce.

1. Back to the 19th Century : the Accumulation of Economic Capital as an Intrinsically Political Phenomenon

1.1. From Political Economy to Its Critique: the Political Underpinnings of Capitalist Accumulation

Putting the question of accumulation back on the job leads to a return to the debates that have run through classical political economy. This is, in the 18th century but especially in the 19th century, witness to a phenomenon unprecedented in its magnitude (Labrousse & Michel, 2017): increasingly guided by the quest for profits, economic activity lends itself, in the main European states, to a significant accumulation of capital ( generally assimilated to the means of production). The phenomenon is – for Adam Smith, in particular – at the foundation of a virtuous social process: accumulation – understood as the broadening of the productive base by adding capital – allows an increase in the number of workers, the division labor, productivity and, ultimately , production. Accumulation and enrichment of nations seem to be linked.

The question of the reproduction of the capitalist economy gradually came to structure the debate on political economy (Denis, 2016 [1966]). Reproduction – that is, the renewal of the production process – presupposes a relative balance between the two major sections – the production of the means of production and that of the means of consumption. According to the categorisations of Rosa Luxemburg (1969 [1913]), the “economists’ quarrel” opposes the “optimists” and the “pessimists”. The first, partisans of balance (that is to say of a harmony of the relations between production and consumption), make accumulation a positive process which, unfortunately, must end in a stationary state that it is a question of pushing back while promoting profit (case of the heirs of Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say and David Ricardo, especially). The latter, liberals (such as Jean de Sismondi) or critics (such as Karl Marx, of course), underline the possibilities of imbalances and crises of general overproduction, pointing out the internal contradictions of the capitalist economy. For the latter, the question of reproduction is all the more thorny in that the mechanisms of capitalism – the competition between the holders of capital, in particular – induce an “enlarged reproduction” of capital, a source of imbalances between production and consumption (the competition leading to a quest for productivity gains to ensure economic survival). Whereas, according to Karl Marx’s categorisations, “simple reproduction” is the repetition of the process in identical proportions to the previous cycle (the surplus value obtained by the capitalist is, in this case, devoted to the purchase of consumer goods), reproduction can be described as expanded when part of the sum of money drawn from surplus value is devoted to the purchase of means of production and/or labor. work, allowing the scale of production to increase. One-word summary: “In the first, the capitalist squanders all the surplus value, in the second, he demonstrates his bourgeois virtues by consuming only part of it and transforming the rest into money [to broaden his base productive]” (Marx, 2006 [1867], p. 656). Extended reproduction is thus confused with the accumulation of capital. allowing the scale of production to be increased. One-word summary: “In the first, the capitalist squanders all the surplus value, in the second, he demonstrates his bourgeois virtues by consuming only part of it and transforming the rest into money [to broaden his base productive]” (Marx, 2006 [1867], p. 656). Extended reproduction is thus confused with the accumulation of capital. allowing the scale of production to be increased. One-word summary: “In the first, the capitalist squanders all the surplus value, in the second, he demonstrates his bourgeois virtues by consuming only part of it and transforming the rest into money [to broaden his base productive]” (Marx, 2006 [1867], p. 656). Extended reproduction is thus confused with the accumulation of capital.

If, in this “quarrel”, the political character of accumulation is secondary, it is not absent; including among liberal economists who consider that the phenomenon presupposes the separation between the class of owners of capital and that of workers 5. From their point of view, the exploitation of the labor of the latter by the former is in a way a necessary evil for raising the standard of living of the community. It is probably Karl Marx who depicted capital and its accumulation as intrinsically political economic phenomena. Indeed, unlike the liberal economists he criticized, his philosophy of history aimed at a radical critique of forms of alienation, so as to bring out what, in social representations and material conditions, founded social relations. of their exploitation (Bartoli, 1984) – an approach that would prove to be the foundation of social sciences (constructivists) 6. Analyzing the genesis of capitalism and contrary to previous treatises on political economy, Karl Marx grasps capital not as wealth but as a social relationship 7. It is the transformation of property relations (notably the advent of private property) that opens up the possibility of a transformation of wealth into capital, private property setting in motion the mechanisms specific to the capitalist economy – taxation at all competitive relationships, incessant quest for better productivity. Seizing capital – and beyond that, accumulation – as a social relationship inevitably leads to making it an intrinsically political phenomenon in that, at a general level of definition, capital and accumulation engage the “relationships of men among themselves”, relations which are moreover conflicting (Lordon, 2008a, p. 12).

Indeed, accumulation is, in its structuring structures, political insofar as it engages power relations which, according to the moments of development of capitalist economies, are sometimes based on physical violence, sometimes on law and silent constraint. economic reports 8 . Thus, the genesis of capitalist economies, which passes through an initial appropriation of wealth by future capitalists (the so-called moment of primitive accumulation in classical political economy), is marked by “crime” and “looting” which alone allow the separation of the means of production between two social classes 9 . The enclosure movement in 17th century England century, constitutes in historiography (Marxist or not) an emblematic expression of the genesis of capitalism (Moore, 1969). In established capitalist economies, the balance of power involved in accumulation is based in particular on law (Palermo, 2007). For Karl Marx, if from a formal point of view it involves two legally equal persons, the separation of the labor force and the means of production generates an asymmetrical power relationship: “[the worker] and the possessor of money meet on the market, and enter into a relationship with each other, with their parity of possessor of goods and this single distinction that one is a buyer, the other is a seller” (Marx, 2006 [1867], p. . 188). The first has the money to build capital, the other does not: ibid. , p. 189). Establishing the asymmetry of the relationship between forces (“the worker works under the control of the capitalist to whom his labor belongs” ( ibid. , p. 208), the labor contract allows the capitalist a legal appropriation of part of the labor unpaid to the worker (the “surplus work”) that the capitalist will have to invest in order to expand his productive base.

In its structured structures, accumulation is for Karl Marx an intrinsically political phenomenon. In Le capital , which offers a more schematic representation of social stratification than other writings by the same author, it is divided into two classes, capitalists and proletarians, the former – endowed with the practical and symbolic force of law (private property and employment contract, in particular) – monopolizing part of the (unpaid) labor of the latter to feed accumulation: “capital is dead labor, which, similar to the vampire, only comes to life by sucking the labor alive, and his life is all the brighter the more he pumps out” ( ibid .., p. 259). In addition to the demands imposed by the conditions of reproduction, exploitation finds some limits with the development of social legislation. Relating the struggles over the establishment of the length of the working day, Karl Marx concludes: “the workers must unite in a single troop and conquer as a class a law of the State, a social obstacle stronger than all, which prevents them from selling themselves to capital by negotiating a free contract, and from pledging themselves and their kind to death and slavery” ( ibid ., p. 338). The feminist critique of Marxism will reveal another social division induced by the development of capitalist economies, which is added to the first: “what we see from the end of the 19th century, with the introduction of the family wage, the male worker’s wage […], it is because the women who worked in the factories were expelled from them and sent back to the home, so that domestic work became their first job, to the point of making them dependent […]. Through the salary, a new hierarchy is created, a new organization of inequality: the man has the power of the salary and becomes the foreman of the unpaid work of the woman” (Federici, 2019, p. 16-17). “Patriarchal capitalism” is emerging: the new organization of the family allows the development of capitalism in that it places in the hands of women the work of reproduction (of the workforce) – unpaid work.

1.2. Veblen and the Analysis of the Power of Businessmen

Under the effect of the marginalist revolution and until the recompositions caused by the Great Depression and the Second World War, the question of accumulation, like that of growth, no longer held much attention: the focus shifted towards microeconomics. However, American institutionalists, and more particularly Thorstein Bunde Veblen (1904, 1914, 1919), were interested in the processes of accumulation and their institutional foundations, in particular mentalities and power. For Veblen, the industrial system was constituted through the accumulation, by the community, of knowledge embodied in technology, and was favored by the artisan instinct of engineers, the institutions of science and rationalism. Gradually, the state of the industrial arts has made workers mere appendages of the technical system and standardized industrial equipment. Equipment and technology have become the going concern around which the presence of the workers was necessary, although auxiliary (1919, p. 14). At the same time, Veblen analyzes the ideological foundations of private property in modern liberalism and the revolutions of the eighteenth century , which was originally conceived as personal property in an economy of small entrepreneurs/individual workers. Subsequently, this was actualized in the ownership of the assets of the business enterprise ( business enterprise ), that is to say capitalist, in a state of the industrial art which no longer corresponded to it. . The owners of the means of production and the business class then developed vested interests , understood as ” the legitimate rights to get something from nothing ”, that is to say the right to obtain the usufruct of this property, without contributing anything to production. Capital, conceived (“invented”) by financiers as a capacity for income, a right to capitalized income on future production, is valued and accumulated by the practices of the business enterprise , which aim to hinder excessive development. of production, under penalty of seeing overproduction and price reductions, through the use of anti-competitive practices and the exploitation of intangible assets (trademarks, goodwill, patents, etc.). Thus, the accumulation of intangible assets also means an accumulation of means of impeding and restricting production in order to increase profitability, all actions which come under what Veblen calls “sabotage” (Veblen, 1921) and more generally predation.

This analysis basically aims to reveal the way in which the “robber barons” acquired a legitimized power of predation, parasitism and rent extraction through a set of practices restricting trade and competition, through the actualization of ownership and “predatory instincts”. Thus, Veblen shows that the accumulation of knowledge and its submission to the property and customs of the business world can harm the majority ( the common man ) and the dominated classes, starting with the workers. For him, capital is thus the product of a power (even if he rarely uses the term), of a vested interest . A thesis taken up more recently and partially by Nitzan and Bichler (2009) when they speak of “ capital as power “. Veblen (1919) was also interested, at the end of the First World War, in the foundations of states, kingdoms, nations and democracies, and in the relations between the business classes and nationalism or imperialism. He shows in particular that, in parallel, kings and political leaders have vested interests (what he calls “the divine rights of kings or Nations”) and that the suppression of kings and their replacement by democratic regimes does not did not have the effect of limiting the impulses of imperialist dominion, the vested interests of the Nation having ended up being confused with the defense of the interests of the business classes. At the same time, the common mentend to feel themselves in solidarity with the upper classes because of their national belonging, and can therefore support warlike adventures ( ibid. , p. 46). Veblen also analyzes inter-imperialist wars.

In short, with regard to the approaches in social sciences which today dominate the study of economic activity, a return to and through classical political economy leads to emphasizing the question of accumulation and to see a political phenomenon, both in terms of its origins (the power relations that found it) and its effects (the power relations that it induces). The historical analyzes of Marx or those of Veblen place, in relation to their predecessors, the question of the social and political structures of accumulation at the top of the scientific agenda. This appears as a social construction, made up of power relations, instituting social relations such as private property and the wage relation, which will be found in the theory of regulation (TR) inspired by the approaches of Marx and the institutionalism.

2. Institutional Dynamics of Accumulation

Classical political economy (notably in its critical version) constitutes a first foundation for the analysis of the political structures of accumulation that we are sketching out here. Certain institutionalist approaches, starting from a critical analysis of the Marxist heritage, and defining institutions as the rules, norms and stabilized conventions which constrain but also “enable” socio-economic activity (Commons, 1934) in are another. We will focus here mainly on work that mobilizes the TR 10. We retain, for the project that is ours, two main assets: the plurality of institutional supports which, in time and space, organize the accumulation (2.1.); the differentiation of the social space in which the strategies of accumulation take shape and develop (2.2.).

2.1. From the “Law of Accumulation” to Regimes of Accumulation

In the 1970s, when the growth of Western economies declined, empirical observation led the economists who would formulate RT to introduce a new research program – the analysis of crises and changes in capitalism (Aglietta, 1976). Here comes the concept of “mode of regulation”, which aims to grasp the resilience of capitalism through the “conjunction” (Boyer & Mistral, 1978, p. 119) of social relations, institutional determinants and private behavior – a conjunction that enables ensemble reproduction. In this perspective, where capitalism is declined in capitalist economies, “the general law of capitalist accumulation” of Marx (2006 [1867], p. 686-802) gives way to “regimes of accumulation”, national analyzes of Fordism revealing institutional configurations located in time and space. Consequently, the study of accumulation becomes that of accumulation regimes. A tool forged to analyze the reproduction of capitalist economies, the concept is defined as “the set of regularities ensuring a general and relatively coherent progression of the accumulation of capital, that is to say making it possible to absorb or spread out in time the distortions and imbalances that constantly arise from the process itself11 ” (Boyer, 2004, p. 20). An arrangement of institutional forms, always specific in time and space, makes it possible to organize and sustain a regime of accumulation. Observation of the Fordist moment has made it possible to identify five fundamental social relations of the capitalist mode of production which are actualized in five institutional forms – understood as codifications of said social relations – according to the modes of regulation: monetary regime, wage relation, labor regime. competition, international regime and state form. The approach revealed a plurality of accumulation regimes. Thus, over time, dominant configurations have succeeded one another – an extensive accumulation in the 19th century (focused on the extension of capitalism to new spheres of activity), intensive accumulation from the interwar period (focused on increasing productivity gains through the reorganization of work), an accumulation driven by finance from the end of the 20th century century (oriented towards the financialization of institutional forms). If accumulation regimes differ over time, they also differ over space. Thus, the regulationist works have shown that Fordism essentially characterized the American case, while the French version knew a more statist regulation. The German or Japanese cases put forward a sometimes meso-corporatist sometimes companyist regulation (Boyer, 2015), with accumulation regimes partly driven by exports. As for the peripheral economies, these were simply not Fordist.

From this conceptualization derive some major achievements, which we retain to build our own approach. The first, of a methodological order, is that the study of accumulation is that of its institutional supports. Once the dynamics of accumulation that marks an economic space at a given time have been objectified, the object of the research focuses on the production (or reproduction) of the institutions that organize it. The construction of the object can be declined on a meso-economic scale. To analyze the transformations that the contemporary French agricultural field is undergoing, Matthieu Ansaloni and Andy Smith (book to be published) take as their subject the regime of accumulation which determines its structure, placing at the heart of their argument the institutions which codify the relations of commercialization. , supply, financing and revenue generation. The construction of the object can also be declined on a macro-economic scale, in the manner of Isil Erdinç and Benjamin Gourisse (2019), when, to analyze the accumulation by the Muslim Turkish bourgeoisie, the Kemalist state expropriates certain ethnic minority fractions. Moreover, the analysis can also take as its object an institution which, because it affects the other components of the regime, weighs on the dynamics of accumulation. Thus, in the present dossier, Matthieu Ansaloni – to analyze the geographical redistribution of cereal production in France – takes as his subject the market institutions which organize competition between competing poles of accumulation. like Isil Erdinç and Benjamin Gourisse (2019), when, to analyze the accumulation by the Muslim Turkish bourgeoisie, the Kemalist state expropriates certain ethnic minority fractions. Moreover, the analysis can also take as its object an institution which, because it affects the other components of the regime, weighs on the dynamics of accumulation. Thus, in the present dossier, Matthieu Ansaloni – to analyze the geographical redistribution of cereal production in France – takes as his subject the market institutions which organize competition between competing poles of accumulation. like Isil Erdinç and Benjamin Gourisse (2019), when, to analyze the accumulation by the Muslim Turkish bourgeoisie, the Kemalist state expropriates certain ethnic minority fractions. Moreover, the analysis can also take as its object an institution which, because it affects the other components of the regime, weighs on the dynamics of accumulation. Thus, in the present dossier, Matthieu Ansaloni – to analyze the geographical redistribution of cereal production in France – takes as his subject the market institutions which organize competition between competing poles of accumulation. the analysis can also take as its object an institution which, because it affects the other components of the regime, weighs on the dynamics of accumulation. Thus, in the present dossier, Matthieu Ansaloni – to analyze the geographical redistribution of cereal production in France – takes as his subject the market institutions which organize competition between competing poles of accumulation. the analysis can also take as its object an institution which, because it affects the other components of the regime, weighs on the dynamics of accumulation. Thus, in the present dossier, Matthieu Ansaloni – to analyze the geographical redistribution of cereal production in France – takes as his subject the market institutions which organize competition between competing poles of accumulation.

The second achievement that we retain, of an ontological and epistemological order this time, is due to the fact that the economic field, the playground of capitalist accumulation, and the economic agents who confront each other there, do not grasp each other as given but as social constructs. As collective representations (Descombes, 2000; Théret, 2000), institutional forms are both external to individuals but also and above all internalized by them. The institutional contexts of economic action frame, and therefore constrain, action: they define the regularities that organize and sustain accumulation. Individuals also internalize institutional contexts: contrary to what the New Economic Sociology postulates, their natural motivation is not the incessant quest for profit, but rather they are caught up in mechanisms – historically constructed – which orient them in this direction (Boyer, 2004). The analysis of the political structures of accumulation (the institutions but also and above all the power relations that affect them) requires empirically resituating the way in which the mechanisms of symbolic imposition that feed bureaucratic struggles as well as the official discourses operate. ‘they generate, as much as the scientific struggles and the dominant expertise that result from them (Roger, 2020).

RT, considered here mainly in its sociological and anthropological dimensions, therefore leads us to understand accumulation through its institutional supports. It also leads us to place at the top of our reflection the strategies of accumulation that unfold in a differentiated social space.

2.2. In Search of Political Structures

An intrinsically political phenomenon, accumulation is, from the origins of RT, understood through its political structures. In his founding analysis of American capitalism, Michel Aglietta (1976, p. 14) intends thus: “to explain the general meaning of historical materialism: the development of the productive forces under the effect of the class struggle and the conditions of the transformation of this struggle and the forms in which it materializes under the effect of this development”. The State is a major stake in economic struggles, in that its policies codify social relations (which have become institutional forms), but also in that its economic policy participates in the mode of regulation and the coherence (or not) of institutional forms. . The sources of inspiration of the TR are multiple to apprehend the policy, whose meaning and conception are diverse (see the article by Éric Lahille in this file). Integrating the contribution of the state to capitalist regulation into the analysis leads some regulationist economists to break with the analysis of the state as a puppet of the capitalist class.12 . Through his theory of the state, Bruno Théret (1992) sets out a framework – forged in the light of the sociological thought of Max Weber, Norbert Elias and Pierre Bourdieu, in particular – for thinking about the political structures of accumulation. The “topology of social space” he proposes is made up of differentiated orders, each endowed with specific stakes, practices and institutions. The economic order, first of all, is one where the domination of man over man is guided by the capitalist logic of the incessant quest for profit by means of the accumulation of material goods and monetary securities. The political order, then, is one where domination is its own end, the economy being put at the service of the accumulation of power viathe concentration of fiscal and military resources. The domestic order, finally, is that in which the human population is reproduced, a population that is subject to exploitation by the other orders of practices 13 . The proposed conceptualization offers some milestones: grasping the institutions – or the regime – that organize accumulation involves identifying the relationships between the forces that oppose each other within the orders of practice that make up the social order. We will specify, in the following section, the way in which we analyze such balances of power.

The work of Bob Jessop sheds additional light. For the English sociologist, if the “circuit of capital” (constituted by institutional forms) sets the institutional context of action, it in no way determines the regime of accumulation: because, echoing the proposals of Bruno Théret, capitalist developments are the fruit of incessant struggles that unfold in multiple social orders, contingency marks their evolution (Jessop, 1990). Such a perspective leads to grasping the games that agents play in order to perpetuate, or even amend, the accumulation regime. To this end, Bob Jessop introduces the notion of “accumulation strategy” and defines it as follows:ibid ., p. 198-199). Economic hegemony therefore corresponds not to a concerted agreement between the dominant fractions of “capital” but more to a sort of temporarily stabilized compromise, in no way exempt from conflict, the model underlying the regime of accumulation allowing them to perpetuate, or even improve, their positions. In this conceptualization, the state is the main target of economic struggles, competing forces clashing to obtain a monopoly over one or another of its segments, investing the social relations of the capitalist economy (which have become institutional forms) with practical and symbolic force of law ( ibid ., p. 201).

Institutions and regimes of accumulation, social space differentiated into distinct orders of practice, strategies of accumulation: the founding arguments of RT offer useful benchmarks for the reflection engaged here. Sociology and political science deliver some complementary conceptual and methodological proposals and allow us to map out the political structures of accumulation.

3. The Political Structures of Accumulation: Fields, Institutions, Political Work

Institutions and regimes of accumulation are what enable, constrain and orient capitalist economic activity: analyzing in depth their genesis and reproduction implies opening a second “front” which specifically concerns the agents who fuel these processes. The analytical challenge is to grasp the action of those who influence the institutions that organize and support accumulation in a given economic space. The production of “institutionalized compromises” involves the capture of a segment of public power (State and/or European Union, for example): more or less faithful expressions of their demands, the institutions seal in return the distribution of economic capital in the economic area considered. Analyzing such a political process implies equipping oneself with tools to grasp differentiated social positions and the struggles that result from them. If we stick to a precise definition and analytical use, the concept of field makes it possible to analyze social positions as combinations of differentiated capitals and to consider that they are part of a structured and structuring whole (3.1 .). The concept of political work makes it possible to analyze the formation of alliances and/or convergences between the agents of a field and beyond (3.2.). From this perspective, nourished by certain achievements of contemporary sociology and political science, the study of the accumulation of economic capital becomes that of the accumulation of capital – economic, social, cultural and symbolic.

3.1. The Political Structuring of Accumulation through the Prism of “Fields”