Archive

Introducing Kuznets Waves: How Income Inequality Waxes and Wanes over the Very Long Run

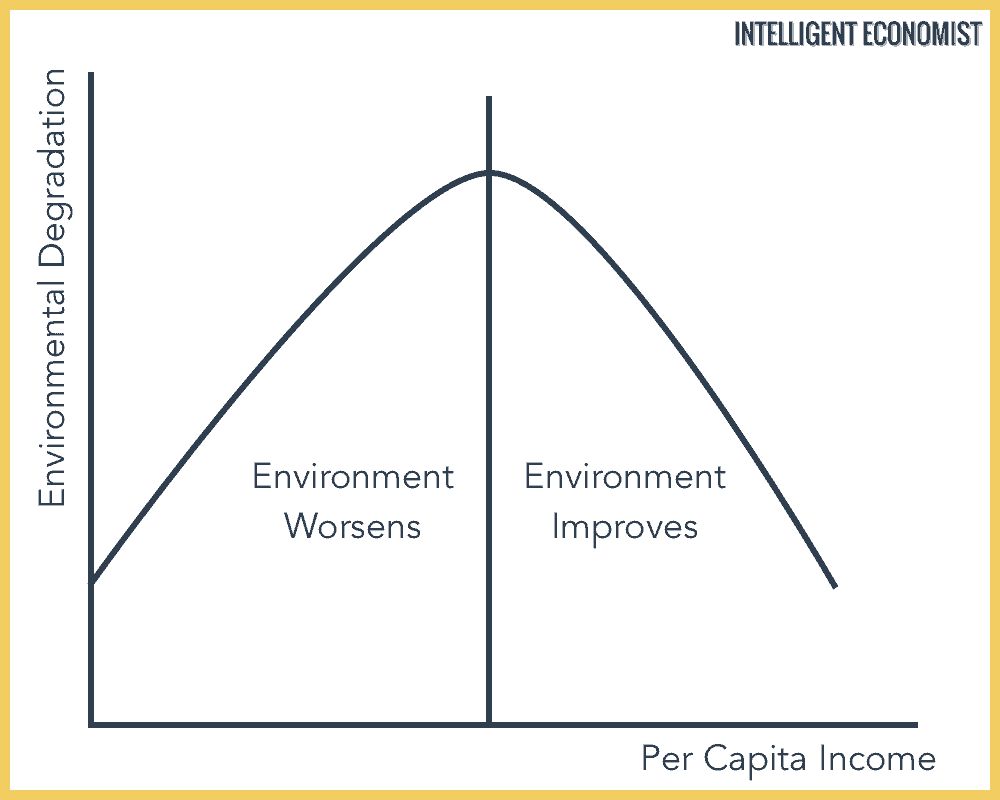

The Kuznets curve was widely used to describe the relationship between growth and inequality over the second half of the 20th century, but it has fallen out of favour in recent decades. This column suggests that the current upswing in inequality can be viewed as a second Kuznets curve. It is driven, like the first, by technological progress, inter-sectoral reallocation of labour, globalization, and policy. The author argues that the US has still not reached the peak of inequality in this second Kuznets wave of the modern era.

In 1955 when Simon Kuznets wrote about the movement of inequality in rich countries (and a couple of poor ones), the US and the UK were in the midst of the most significant decrease of income inequality ever registered in history, coupled with fast growth. It thus seemed eminently reasonable to look at the factors behind the decrease of inequality, and Kuznets famously found them in expanded education, lower inter-sectoral productivity differences (thus the rent component of wages would be equalized), lower return to capital, and political pressure for greater social transfers. He then looked at (or rather imagined) the evolution of inequality during the previous century and thought that, driven by the transfer of labour from agriculture to manufacturing, inequality rose and reached its peak in the rich world sometime around the turn of the 20th century. Thus, he created the famous Kuznets curve.

The Kuznets curve was the main tool used by inequality economists when thinking about the relationship between development or growth and inequality over the past half century. But the Kuznets curve gradually fell out of favor because its prediction of low inequality in very rich societies could not be squared with the sustained increase in income inequality that started in the late 1970s in practically all developed nations (see the long-run graphs for the US and the UK). Many people thus rejected it.

The Upswing in Current Inequality as a Second Kuznets Curve

In a new book (Milanovic 2016), I argue however that we should see the current upswing in inequality as the second Kuznets curve in the modern times, being driven, like the first, mostly by a technological revolution and the transfer of labour from more homogenous manufacturing into skill-heterogeneous services (and thus producing a decline in the ability of workers to organize), but also (again like the first) by globalization, which has both led to the famous hollowing out of the middle classes in the west and to a pressure to reduce high tax rates on mobile capital and high-skilled labour. The elements listed here are not new. But putting them together (especially viewing technological progress and globalization as practically indissoluble, even if conceptually different) and viewing this as part of regular Kuznets waves is new. It has obvious implications for the future, not the least that this bout of inequality growth will peak like the previous one and eventually go down.

But before I address that part, let us consider recent important work done by economic historians such as van Zayden (1995); Nogal and Prados (2013); Alfani (2014) and Ryckbosch (2014), who have documented periods of waxing and waning inequality in pre-modern Europe. The interesting part is that Kuznets cycles in pre-modern societies basically replicate the Malthusian cycles because they take place in conditions of quasi-stationary mean income. The pre-modern Kuznets cycles are not driven by economic factors but by epidemics and wars. Both lead to a decrease in population, an increase in mean income, higher wages (because of labour scarcity) and thus lower inequality, that is, until population growth in a Malthusian fashion reverses all these gains.

Thus, we can observe Kuznets waves over some six or seven centuries of European history. In pre-modern times, they are observable against time because mean income is more or less constant (it is just one point on the x-axis). After the Industrial Revolution, however, we see the waves responding to economic factors (e.g. technological change, transfer of labour), and can plot them as Kuznets thought against mean income. This is shown here in the graphs for the US and the UK (Figure 1 and 2). In addition, I show in my book long-term inequality cycles for Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, Japan, Brazil, Chile, and over a shorter period for China.

While Kuznets’ explanation was focused almost entirely on economic and thus ‘benign’ forces, he was wrong to overlook the impact of ‘malign’ forces (especially wars) that are powerful engines of income equalisation. I find this somewhat puzzling because Kuznets himself, having worked during World War II in the US Bureau of Planning and Statistics, must have noticed how the war led to the compression of income through higher taxation, financial repression, rationing, price controls, and even sheer destruction of physical assets (as in Europe and Japan).

Inequality May Not Be Overturned Soon

Which leads us to the present. How long will the current upswing of the Kuznets wave continue in the rich world, and when and how will it stop? I am skeptical that it will be overturned soon, at least not in the US where I see four powerful forces that keep on pushing inequality up. I will just list them here (they are, of course, discussed in the book):

- Rising share of capital income which is in all rich countries extremely concentrated among the rich (with a Gini in excess of 90);

- Growing association of high incomes from both capital and labour in the hands of the same people (Atkinson and Lakner 2014);

- Homogamy (the educated and the rich marrying each other); and

- Growing importance of money in politics which allows the rich to write rules favourable to them and thus to maintain the inequality momentum (Gilens 2012).

The peak of inequality in the second Kuznets wave should be lower than in the first (when in the UK, it was equal to the inequality level of today’s South Africa) because the rich societies have in the meantime acquired a number of ‘inequality stabilizers’, from unemployment benefits to state pensions.

The pro-inequality trends will be very hard to overturn during the next generation, but eventually they may be – through a combination of political change, pro-unskilled labour technological innovations (which will become more profitable as skilled labor’s price increases), dissipation of rents acquired during the current bout of technological efflorescence, and possibly greater attempts to equalize ownership of assets (through forms of ‘people’s capitalism’ and workers’ shareholding).

Now, these are of course the benign factors that, I think, will ultimately set inequality in rich countries on its downward path. But history teaches us too that there are malign factors, notably wars, in turn caused by domestic maldistribution of income and power of the elites (as was the case in the World War I), that can also do the job of income levelling. But they do it at the cost of millions of human lives. One can hope that we have learned something from history and would avoid this destructive path to equality in poverty and death.

References

Alfani, G (2014), “Economic inequality in the northwestern Italy: a long-term view (fourteenth to eighteenth century)”, Dondena Working Paper No. 61, Bocconi University, Milano.

Alvarez-Nogal, C and L Prados de la Escosura (2013), “The rise and fall of Spain (1270–1850),” Economic History Review, vol. 66(1), pages 1-37.

Atkinson, A and C Lakner (2014), “Wages, capital and top incomes: The factor income composition of top incomes in the USA, 1960-2005”, November version.

Gilens, M(2012), Affluence and Influence, Princeton University Press.

Kuznets, S (1955), “Economic growth and income inequality”, American Economic Review, March, pp. 1-28.

Milanovic, B (2016), Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization, Harvard University Press.

Ryckbosch, W (2014), “Economic inequality and growth before the Industrial Revolution: A case study of Low countries (14th-16th century), Dondena Working Paper No. 67, Bocconi University, Milano.

van Zanden, J L (1995), “Tracing the beginning of the Kuznets curve: western Europe during the early modern period”, The Economic History Review, vol. 48, issue 4, pp. 1-23. November.

Can Democracy Help with Inequality?

Inequality is currently a prominent topic of debate in Western democracies. In democratic countries, we might expect rising inequality to be partially offset by an increase in political support for redistribution. This column argues that the relationship between democracy, redistribution, and inequality is more complicated than that. Elites in newly democratized countries may hold on to power in other ways, the liberalization of occupational choice may increase inequality among previously excluded groups, and the middle classes may redistribute income away from the poor as well as the rich.

There is a great deal of concern at the moment about the consequences of rising levels of inequality in North America and Western Europe. Will this lead to an oligarchisation of the political system, and imperil political and social stability? Many find such dynamics puzzling given that it is happening in democratic countries. In democratic societies, there ought to be political mechanisms that can inhibit or reverse large rises in inequality, most likely through the fiscal system. Indeed, one of the most central models in political economy, due originally to Meltzer and Richard (1981), suggests that high inequality in a democracy should lead the politically powerful (in their model the voter at the median of the income distribution) to vote for higher levels of taxes and redistribution, which would partially offset rising inequality.

But before asking about what happens in a democracy, we could start with some even more fundamental questions. Is it correct factually that democracies redistribute more income than dictatorships? When a country becomes democratic, does this tend to increase redistribution and reduce inequality? The existing scholarship on these questions, though vast, is quite contradictory. Historical studies, such as Acemoglu and Robinson (2000) and Lindert (2004), tend to suggest that democratization increases redistribution and reduces inequality. Using cross-national data, Gil et al. (2004) find no correlation between democracy as measured by the Polity score and any government spending or policy outcome. The evidence on the impact of democracy on inequality is similarly puzzling. An early survey by Sirowy and Inkeles (1990) concludes, “the existing evidence suggests that the level of political democracy as measured at one point in time tends not to be widely associated with lower levels of income inequality” (p. 151), though Rodrik (1999) finds that both the Freedom House and Polity III measures of democracy were positively correlated with average real wages in manufacturing and the share of wages in national income (in specifications that also control for productivity, GDP per capita, and a price index).

In a recent working paper (Acemoglu et al. 2013), we revisit these questions both theoretically and empirically.

Theoretical Nuances

Theoretically, we point out why the relationship between democracy, redistribution, and inequality may be more complex than the discussion above might suggest. First, democracy may be ‘captured’ or ‘constrained’. In particular, even though democracy clearly changes the distribution of de jure power in society, policy outcomes and inequality depend not just on the de jure but also the de facto distribution of power. Acemoglu and Robinson (2008) argue that, under certain circumstances, elites who see their de jure power eroded by democratization may sufficiently increase their investments in de facto power (e.g. via control of local law enforcement, mobilization of non-state armed actors, lobbying, and other means of capturing the party system) in order to continue to control the political process. If so, we would not see much impact of democratization on redistribution and inequality. Similarly, democracy may be constrained by other de jure institutions such as constitutions, conservative political parties, and judiciaries, or by de facto threats of coups, capital flight, or widespread tax evasion by the elite.

Democratization can also result in ‘inequality-increasing market opportunities’. Non-democracy may exclude a large fraction of the population from productive occupations (e.g. skilled occupations) and entrepreneurship (including lucrative contracts), as in Apartheid South Africa or the former Soviet Union. To the extent that there is significant heterogeneity within this population, the freedom to take part in economic activities on a more level playing field with the previous elite may actually increase inequality within the excluded or repressed group, and consequently the entire society.

Finally, consistent with Stigler’s ‘Director’s Law’ (1970), democracy may transfer political power to the middle class, rather than the poor. If so, redistribution may increase and inequality may be curtailed only if the middle class is in favour of such redistribution.

But what are the basic robust facts, and do they support any of these mechanisms?

Empirical Evidence

Cross-sectional (cross-national) regressions, or regressions that do not control for country fixed effects, will be heavily confounded with other factors likely to be simultaneously correlated with democracy and inequality. In our work we therefore focus on a consistent panel of countries, and investigate whether countries that become democratic redistribute more and reduce inequality relative to others. We also focus on a consistent definition of democratization based on Freedom House and Polity indices, building on the work by Papaioannou and Siourounis (2008).

One of the problems of these indices is the significant measurement error, which creates spurious movements in democracy. To minimize the influence of such measurement error, we create a dichotomous measure of democracy using information from both the Freedom House and Polity data sets, as well as other codings of democracies, to resolve ambiguous cases. This leads to a binary measure of democracy for 184 countries annually from 1960 (or post-1960 year of independence) to 2010. We also pay special attention to modeling the dynamics of our outcomes of interest – taxes as a percentage of GDP, and various measures of structural change and inequality.

Our empirical investigation uncovers a number of interesting patterns. First, we find a robust and quantitatively large effect of democracy on tax revenues as a percentage of GDP (and also on total government revenues as a percentage of GDP). The long-run effect of democracy in our preferred specification is about a 16% increase in tax revenues as a fraction of GDP. This pattern is robust to various different econometric techniques and to the inclusion of other potential determinants of taxes, such as unrest, war, and education.

Second, we find an effect of democracy on secondary school enrolment and the extent of structural transformation (e.g. an impact on the nonagricultural shares of employment and output).

Third, however, we find a much more limited effect of democracy on inequality. Even though some measures and some specifications indicate that inequality declines after democratization, there is no robust pattern in the data (certainly nothing comparable to the results on taxes and government revenue). This may reflect the poorer quality of inequality data. But we also suspect it may be related to the more complex, nuanced theoretical relationships between democracy and inequality pointed out above.

Fourth, we investigate whether there are heterogeneous effects of democracy on taxes and inequality consistent with these more nuanced theoretical relationships. The evidence here points to an inequality-increasing impact of democracy in societies with a high degree of land inequality, which we interpret as evidence of (partial) capture of democratic decision-making by landed elites. We also find that inequality increases following a democratisation in relatively nonagricultural societies, and also when the extent of disequalising economic activities is greater in the global economy as measured by US top income shares (though this effect is less robust). These correlations are consistent with the inequality-inducing effects of access to market opportunities created by democracy. We also find that democracy tends to increase inequality and taxation when the middle class are relatively richer compared to the rich and poor. These correlations are consistent with Director’s Law, which suggests that democracy allows the middle class to redistribute from both the rich and the poor to itself.

Conclusions

These results do suggest that some of our basic intuitions about democracy are right – democracy does represent a real shift in political power away from elites that has first-order consequences for redistribution and government policy. But the impact of democracy on inequality may be more limited than one might have expected.

This might be because recent increases in inequality are ‘market-induced’ in the sense of being caused by technological change. But at the same time, our work also suggests reasons why democracy may not counteract inequality. Most importantly, this may be because, as in the Director’s Law, the middle classes use democracy to redistribute to themselves. Nevertheless, since the increase in inequality in the US has been associated with a significant surge in the share of income accruing to the very rich, compared to both the middle class and the poor, Director’s Law-type mechanisms seem unlikely to be able to explain why policy has not changed to counteract this. Clearly other political mechanisms must be at work, the nature of which requires a great deal of research.

References

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson (2000), “Why Did the West Extend the Franchise?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115: 1167–1199.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson (2008), “Persistence of Power, Elites and Institutions”, The American Economic Review, 98: 267–291.

Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A Robinson (2013), “Democracy, Redistribution and Inequality”, NBER Working Paper 19746.

Gil, Ricard, Casey B Mulligan, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin (2004), “Do Democracies have different Public Policies than Nondemocracies?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18: 51–74.

Lindert, Peter H (2004), Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth since the Eighteenth Century, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Meltzer, Allan M and Scott F Richard (1981), “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government”, Journal of Political Economy, 89: 914–927.

Papaioannou, Elias and Gregorios Siourounis (2008), “Democratisation and Growth”, Economic Journal, 118(532): 1520–1551.

Rodrik, Dani (1999), “Democracies Pay Higher Wages”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114: 707–738.

Sirowy, Larry and Alex Inkeles (1990), “The Effects of Democracy on Economic Growth and Inequality: A Review”, Studies in Comparative International Development, 25: 126–157.

Stigler, George J (1970), “Director’s Law of public income redistribution”, Journal of Law and Economics, 13: 1–10.

New Developmentalism: Macroeconomics for Developing Countries

After developing remarkably over the course of the 20th Century, the Brazilian economy stagnated in the 1980s, as a consequence of high inflation and a substantial foreign debt crisis.

Since 1994, despite these two obstacles having been overcome, the country’s growth per capita has been limited to 1% per year, down from an average of 4.5% between 1950 and 1980.

In 2007, I wrote Macroeconomics of Stagnation in order to develop a new theory to understand and explain the Brazilian economy’s poor performance. This article is about the application of that theory to Brazil. The 2007 essay garnered little attention when it was published because a commodities boom caused the Brazilian economy to skyrocket, but the following years confirmed my diagnosis. Globalization and Competition (2010) and Developmental Macroeconomics (2016, co-authored with Nelson Marconi and José Luiz Oreiro), represent a more extensive articulation of the theory.

The theory gradually took shape and received a name: new developmentalism. Inclusive of development macroeconomics and a political economy of developmental capitalism, the theory contrasts with two extremes: liberal capitalism and statism.

New developmentalism’s macroeconomics is innovative in how it addresses the exchange rate and the current account balance and by virtue of its focus on the five macroeconomic prices: the interest rate; the exchange rate; the wage rate; the rate of profit; and the rate of inflation.

Education, institutions, investment in infrastructure, a financial system able to facilitate investment, and sustained demand are all essential to the economic development process. I argue that the exchange rate and the current account balance are just as essential, and, together with sustained demand, their outcomes are short-term.

Of all the macroeconomic prices, the exchange rate has received least interest from economics. In The General Theory of Employment (1936), John Maynard Keynes created a ‘closed’ economy model involving no foreign trade and posited a fixed exchange rate, thereby excluding exchange rate policy from his book.

Liberal or neo-classical economists believe the exchange rate is satisfactorily determined by the market and their only proposal in this regard is free currency exchange.

Classical development economists like Arthur Lewis, Albert Hirschman, Raúl Prebisch, and Celso Furtado understood the importance of the exchange rate, but instead of arguing for a competitive rate, they proposed a problematic substitute to foster industrialisation: high tariffs on imports of manufactured goods.

Many still believe the exchange rate is only important in its effect on imports and exports but it is crucial for inflation as well. According to new developmentalism, the exchange rate is a significant determinant of investment and savings, and therefore of economic development.

An exchange rate that is overvalued in the long run makes a country’s manufacturing firms uncompetitive, discourages investment, and thereby becomes an obstacle to growth. In addition, the corresponding current account deficit leads the country into a balance-of-payments crisis. Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of economists fails to recognize the importance of current account deficits. They are rightly concerned with the fiscal indiscipline expressed by severely high public deficits but are deeply mistaken to not argue for exchange rate discipline as well, in order to guard against severe current account deficits.

1. Against Current Account Deficits

A theory possesses value if in addition to being true to fact it is also counter-intuitive. The simple replication of common wisdom is not good science.

New developmentalism’s macroeconomics begins with a counter-intuitive principle: middle-income countries like Brazil do not need foreign capital. Current account deficits, which are necessarily financed by foreign funds, hamper economic development rather than fostering it. The notion that capital-poor countries must attract capital from rich ones seems true, but is misguided.

The argument for taking on foreign debt is that a current account deficit equates to ‘foreign savings’ and that foreign savings and domestic savings together make up total savings, which always spells investment. This, however, is an accountant’s reasoning, not an economist’s. An economist thinks in terms of cause and effect, not in terms of identities.

When a country has a current account deficit, its exchange rate rises in parallel; secondly, the revenues of labourers (wages) and rentiers (interest, rent, and dividends) increase in real terms; thirdly, profits fall, discouraging firms from investing, while workers and rentiers are encouraged to consume. The influx of foreign funds, therefore, leads to a high level of substitution of domestic savings for foreign savings.

The only situation in which the substitution of domestic for foreign savings will not be as significant is when a country is already experiencing very marked growth when investment opportunities are multiplying, and the propensity to invest is increasing. The last time this occurred in Brazil was during the 1968-1973 economic ‘miracle’.

As figure 1 shows, there is a direct link between the current account balance (horizontal axis) and the exchange rate (vertical axis). A current account deficit corresponds to a higher exchange rate than that required for a balanced current account.

This can be illustrated by a country like Brazil, which has already industrialised but exhibits a very slow growth rate, low investment and savings rates, and high public and current account deficits.

In a country like this, an exchange rate that would keep the current account at zero is R$3.30 to the US dollar, whereas an exchange rate that would enable manufacturing companies to be competitive is R$4.00 to the US dollar, corresponding to a current account surplus of 1% of GDP. In the same country, a current account deficit of 3% of GDP would correspond to a higher exchange rate of R$2.80 to the US dollar. Figure 1 displays this correlation.

When a government decides to pursue growth through foreign savings, it, therefore, decides to incur a current account deficit. The decision is self-defeating because the growing current account deficit denotes an exchange rate that in the long run, is so high as to make technologically competitive companies (i.e., those using the best technology available) uncompetitive in monetary terms.

By accommodating a current account deficit, the government engages in exchange rate populism: the country incurs a current account deficit that causes wages interests, real estate rents, and dividends to be artificially high, rather than encouraging investment and growth.

In order for Brazilian firms (be they local or multinational) to remain internationally competitive, the government must ensure an exchange rate of around R$4.00 to the US dollar, corresponding to a current account surplus of just over 1% of GDP.

This idea is counter-intuitive because it means the country does not need foreign funds. In fact, by incurring a current account surplus the country will grow while reducing its foreign debt, increasing its international reserves, and/or financing local companies investing abroad.

2. Dutch Disease

In the example above, the exchange rate that balances the current account, or holds it at zero (R$3.30 to the US dollar) is the ‘current equilibrium’ exchange rate. The competitive or ‘industrial equilibrium’ exchange rate is different – at around R$4.00 to the US dollar – because the country suffers from the Dutch disease. In this example, the Dutch disease represents the R$0.70-to-the-US-dollar difference between the industrial and current equilibriums.

The Dutch disease is a long-term over appreciation of a country’s currency caused by commodities exports which – whether due to a momentary boom in prices or differential or Ricardian rents – can be profitably exported at an exchange rate significantly higher than that enabling state-of-the-art manufacturing firms to remain internationally competitive.

Although the Dutch disease represents a R$0.70-to-the-US-dollar differential in this example, it may be far greater in other cases, especially in oil-exporting countries where the cost of extraction is very low. The severity of this competitive disadvantage will vary in accordance with international commodities prices.

A country affected by the Dutch disease will experience a current account surplus. In figure 2, with the exchange rate on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis, the two equilibriums are shown by the near-parallel red and blue lines: the current equilibrium is the lower red line, and industrial equilibrium is the blue line above. In a commodities-exporting country, commodities will determine the current equilibrium because this equilibrium corresponds to a satisfactory rate of profit for local producers.

Neutralising the Dutch disease means raising the current equilibrium to the level of the industrial equilibrium. Because the latter is higher than the former, this means that neutralising the Dutch disease and thereby ensuring a competitive playing field for firms operating abroad necessarily involves a current account surplus.

The two equilibriums vary over time. For the purposes of this article, it suffices to say that the industrial equilibrium varies mainly with increased productivity and rising manufacturing wages, whereas the current equilibrium varies mainly with changes in commodity prices.

How can the Dutch disease be neutralised? Before it was properly acknowledged, the Dutch disease was neutralised intuitively through high customs tariffs. Governments justified this using the infant industry argument, while critics accused governments of protectionism. However, in many cases, high customs tariffs aimed to neutralise the Dutch disease for the sake of the foreign market.

The United States, for example, endured the Dutch disease due to oil exports, so maintained high tariffs until 1939. To speak of an infant industry at that point would have been absurd, and nor does it make sense to think in terms of protectionism. In fact, high tariffs were a necessary condition for US industrialisation. The US stopped neutralising the Dutch disease in 1939 because it was already very rich and – because of the war – it lacked competitors.

Ordinarily, countries neutralize the Dutch disease from a certain stage of development onwards, following an import substitution model of industrialization. To this end, they subsidize exports of manufactured products in addition to implementing high import tariffs on foreign goods. Brazil did this successfully between 1967 and 1990. In 1965, manufactured goods exports represented just 6% of total exports; this had risen to 62% by 1990!

The WTO now forbids subsidies. The alternative is to tax commodities exports at variable rates based on commodity prices, whereby, in the Brazilian case, the exporter of a certain commodity would pay 0.70 per US dollar of exports earned. As a consequence of the reduced supply caused by the tax, the exchange rate would depreciate, thereby re-establishing supply, with the manufacturing industry becoming internationally competitive. The tax on commodities exports would lead the market to automatically equalize the current and industrial equilibriums.

This is a very interesting way to neutralise the Dutch disease because ultimately it doesn’t cost exporters anything. What they pay, they receive back in full by way of currency depreciation.

3. Exchange Rate Overvaluation

Figure 2 also shows a third curve, with cyclical behaviour expressed by two peaks; this is the real exchange rate curve. If the market operated as liberal economists assume, the curve would float around the current equilibrium. We know, however, that this is not the case.

According to new developmental macroeconomics, in developing countries afflicted by the Dutch disease, severe long-term exchange rate overvaluation is typical, leading the economy from one financial crisis to another. The peaks correspond to financial crises, after which the exchange rate falls sharply.

In Brazil’s case, this occurred in 2002 and 2014, when the exchange rate briefly rose above the industrial equilibrium. The exchange rate then crossed beneath the industrial equilibrium, then the level of the current equilibrium, to enter the area representing a current account deficit (between the real exchange rate and the current equilibrium), finally stabilizing for a few years at a ‘bottom level’ that was not good for commodities, but enough to keep producers exporting.

Two things cause the exchange rate to rise after a crisis: the Dutch disease and very high interest rates. The Dutch disease ‘pulls’ the exchange rate only as far as the current equilibrium because, for a commodities exporting country, it is commodities that determine the current equilibrium. But the exchange rate continues to drop below the current equilibrium. This is because a commodities exporting country implements substantially higher interest rates than rich countries. Finally, the exchange rate reaches a bottom level, which, in the Brazilian case, was around R$2.80 to the US dollar (at today’s prices) from 2007 to 2017, accompanied by drastic deindustrialisation and quasi-stagnation.

While the exchange rate fluctuates around this bottom level, the current account deficits incurred year after year gradually increase firms’ foreign currency-denominated debt and therefore the debt of the country.

Because the exchange rate regime is free-floating, the deficits should cause the country’s currency to depreciate, but this is prevented by the forming of a credit bubble. Foreign creditors are happy to benefit from high interest rates, economists explain the deficits as ‘foreign savings’, beneficial for the country, and creditors continue to gladly extend credit. In consequence, local manufacturers become internationally uncompetitive and accumulate debt.

Usually, more than half of the foreign debt is financed through foreign investment, which only extends the period of overvaluation. But creditors eventually realize the risk of sovereign default and suspend refinancing of the foreign debt. Alternatively, multinational companies, fearful of being unable to repatriate profits, stop investing. Local firms (manufacturers especially) which have been forced to take on debt, having ceased to be competitive, may also conclude they have to stop accumulating debt. In any case, firms stop investing and a financial crisis is triggered, while the exchange rate rises sharply once again.

Interest rates in developing countries are usually justified by two ‘needs’: that of attracting foreign capital, and that of using the exchange rate as an anchor against inflation.

It should be clear that a policy designed to attract foreign capital is self-defeating.

Central banks have to use interest rates to fight inflation. The level of the real interest rate around which the central bank conducts policy is particularly important. It is fine for this level to be a little lower than that of rich countries, but nothing justifies a much higher level. A third cause for high interest rates can be their benefit to rentiers and financiers, which is perverse when one realises that healthy economies in democratic countries are characterised by low interest rates. Justifying high rates through foreign savings is a mistake: the resulting exchange rate rise leads to higher levels of consumption rather than higher levels of investment.

The use of the exchange rate as an anchor against inflation is absurd. Economists are outraged when governments hold back the prices of state-owned companies (like Petrobras, for example) to keep inflation under control; they should be similarly outraged when central banks hold back the ‘price of the country’: the exchange rate.

4. Financial Crises

Every country is subject to financial crises, which mainly consist of banking crises in rich countries and balance-of-payment or foreign exchange crises in developing countries.

Conventional economics explains crises away in terms of fiscal irresponsibility. Indeed, financial crises may stem from this: excessive government spending can cause increases in demand, imports, and ultimately, fiscal and current account deficits. When these occur together, they are referred to as the ‘twin deficits’.

Still, crises may emerge in the absence of fiscal indiscipline, simply as a consequence of policies of growth through foreign savings.

These days, government fiscal accounts are increasingly scrutinised by rating agencies, financial economists, and the press, so that imbalances like those of the Rousseff Administration are more of an exception than a rule amongst middle-income countries.

On the other hand, current account deficits and the indebtedness of firms do not receive the same level of attention from conventional economists, be they liberal or developmental, because they mistakenly assume the market will provide appropriate controls. It is therefore understandable that these deficits are the main causes of developing countries’ financial crises.

5. The Exchange Rate and Development

Investment is the key variable in the development process. The state’s economic role in contemporary societies is to provide equitable income distribution and ensure conditions for capital accumulation. In this latter role, firstly, it has to provide education; secondly, institutions that ensure market efficiency; thirdly, infrastructure investment; fourthly, long-term finance, and fifthly, a stable national currency.

Keynes diagnosed capitalism’s tendency for insufficient demand and added a sixth condition: demand for investment. New developmentalism adds a seventh general condition: an exchange rate capable of ensuring firms’ access to demand. The exchange rate is like a switch that will turn access to foreign and domestic markets on or off.

Economic development textbooks do not discuss exchange rates because they are seen to represent short-term problems and economic development is chiefly interested in long-run trends. Exchange rates are acknowledged to be volatile, but this volatility does not occur around the current equilibrium. If that were the case, its negative effect on investments would be relatively small because businessmen would not take a higher interest rate for reference when making their investment calculations.

New developmentalism views the problem differently because it is the only theory accounting for the fact developing countries have a tendency for cyclical and long-run exchange rate overvaluation in-between financial crises.

In Brazil, for example, the exchange rate remained overvalued for seven years from 2007 to 2014, during which it hovered around R$2.80 to the US dollar. Under these conditions, businesses find investment does not help them remain competitive, even if using state-of-the-art technology, and choose not to invest.

6. Economic Policy

To ensure increases in savings and investment, macroeconomic policy must not only guarantee fiscal responsibility but exchange rate responsibility as well, with an even greater focus on the latter because current account deficits are less justifiable than public deficits.

Of paramount importance is that five key prices are effectively controlled: low interest rates; competitive exchange rate; wage rates compatible with rates of profit sufficient to provoke investment; and a low rate of inflation.

The exchange rate is the most important of these five prices. Exchange rates should be maintained close to the industrial, or competitive, equilibrium. In other words, cyclical exchange rate overvaluation must be neutralised to ensure firms can access both foreign and domestic demand. Industrial policy is also necessary, but as a supplement, never a substitute, for macroeconomic policy.

In order to maintain a competitive exchange rate, the Dutch disease should be neutralised through a variable tax on commodities exports, and should also reject the three policies habitually embraced by developing countries which cause additional currency appreciation: the policy of growth through foreign debt; the use of the exchange rate as an anchor against inflation; and – the policy used to enable the former two – high interest rates.

Central banks should certainly use interest rates to combat inflation, but it should be kept low – slightly above rich country rates. Because central banks are responsible for keeping inflation in check, they are constantly tempted to keep interest rates high and the exchange rate overvalued. That is why central banks should be responsible for growth in addition to inflation. As is already the case in certain countries, exchange rate policy committees should operate similarly to existing monetary policy committees. Naturally, the government should also be able to control capital flows.

7. Where the Difficulty Lies

The theory is simple and so is the exchange rate policy that derives from it. New developmentalism explains why so many developing countries face the competitive disadvantage of long-term exchange rate overvaluation and are therefore unable to industrialize, and why middle-income industrialised countries which dismantle their mechanisms for neutralising the Dutch disease then deindustrialise, as has been the case in Brazil.

The reason countries like Brazil have followed the course they have is the pressure received from the rich world since the 1980s, when developing countries surrendered to economic liberalism and opened up their economies, thereby dismantling mechanisms which had previously prevented exchange rate overvaluation: import tariffs and subsidies for the production of manufactured goods.

New developmentalism explains the fortunes of deindustrialising middle-income countries and offers policy responses. But now that the theory is available, why don’t developing countries, Brazil included, embrace the necessary policies?

Firstly, in spite of interest from younger scholars, trained economists have enormous trouble learning and internalising new things.

Secondly, there is a short-run cost involved in shifting from a current account deficit to a surplus. The necessary one-time devaluation reduces the income of both workers and rentier capitalists.

The fact neither workers nor rentiers like devaluation is why development economists who defend the short-term interests of wage-earners, and liberal economists who basically represent the interests of rentiers and financiers, are both opposed to devaluation.

Rentiers oppose devaluation with a better reason than workers. For the latter, a depreciation will cause wages to lose purchasing power in the short run, but they will soon be rewarded with additional jobs, and later, with increased productivity and higher wages. For rentiers, the picture is different. A devaluation will similarly reduce the purchasing power of their revenues (interests, dividends, and real estate rents), but also the worth of their wealth. Devaluation will also occur only via an interest rate cut, which definitely runs counter to rentier interests. That is why – besides the neo-liberal education they receive in American and British universities – liberal economists refuse to countenance a competitive exchange rate and inevitably ‘forget’ exchange rates when discussing developing countries’ economic problems.

Faced with the macroeconomic issues caused by large current account deficits and public deficits, liberal economists merely propose fiscal adjustment. By causing recessions and unemployment, sole reliance on fiscal measures reduces interest rates and makes the national currency more competitive without devaluing it. In this way, only waged and salaried workers pay for the adjustment by way of a drop in wages.

New developmentalism’s proposals include fiscal adjustment too but alongside a simultaneous cut in interest rates and a currency devaluation. This leads to a more complete adjustment of the country’s accounts and a more equitable distribution of the cost of the adjustment.

Under conditions of ‘liberal’ adjustment, costs are entirely borne by workers, who lose their jobs and see their wages and salaries reduced. In contrast, the bill for new developmentalism-style adjustment is distributed between wage earners and rentiers.

The Surplus Approach to Rent

Theories of rent are wide-ranging. However, whether neoclassical, Marxist, or Proudhonist, they tend to neglect evolutionary institutionalist theorising. Increasingly dominated by the income approach, rent theories need to be expanded, partly to correct existing work, partly to break persistent intellectual monopoly and oligopoly, and particularly to develop institutional theories of rent. In this paper, I attempt to do so by presenting and evaluating the surplus approach to rent, particularly R.T. Ely’s, highlighting its power and potential and stressing its critiques and contradictions. Drawing, among others, on the original writings of Ely, it is argued that, while the emphasis on property rights, land as a ‘bundle of sticks’, and rent as surplus rather than income help to advance heterodox approaches to rent, the surplus approach is severely limited in its analysis of inequalities and how they can be addressed, especially in extractivist and rentier societies. To unravel long-term inequalities that characterize rent and rentier economies, it is crucial for surplus theorists to engage stratification economics which, in turn, can drive the surplus approach to rent.

1. Rent: Beyond Income

Neoclassical economists define rent as the price paid for the use of land obtained in a competitive market (see, for example, O’Sullivan, 2012, p. 157-161). Therefore, rent is an open-market price paid for the use of land – much like interest is income for the use of capital. In this income approach, rent functions as a driver of growth. Also, rent – like price, more generally – becomes a mechanism for allocating land as a scarce resource.

The surplus approach to rent is rather different. Advanced by a wide range of classical and other economists, including the physiocrats, Smithians, Ricardians, Georgists, institutionalists, Marxists and the French Régulationists, rent is not simply the return price for the use of land; it is also surplus (Ely, 1922, 1927; Haila, 1990, 2016; Fine, 2019; Faudot, 2019). Every surplus approach offers a critique of approaches in neoclassical economics and their related policy prescriptions, but the surplus approach also provides a comprehensive and coherent alternative framework to analyse extractivism and other socio-ecological problems (Butler, 2002). In practice, the surplus approach also offers a springboard for developing practical transformative steps and policies to change the world.

Beyond these generalities, the surplus approach has many nuances. Various theorists have debated what land rent is, and what it is not. Many analysts focus on regimes of growth, particularly the French régulationnistes (See, for example, Faudot, 2019, the work of Robert Boyer, and its extensive discussion, including Vercueil, 2016; Harada & Uemura, 2019). When determining how to address inequality, they deal with the question of rent as a surplus, but how to deal with that surplus and whether to emphasise growth or inequalities, land or capital varies widely. Generally, in the surplus approach, a critical question is whether to re-invest the surplus “to expand and transform the existing economic system”, whether the surplus should be ‘wasted in luxury consumption, leading to economic decline’ (Martins, 2018, p. 41), or whether to redistribute the surplus for inclusive economic development. What proportion of land rent should be returned to the landowner? Should a landowner whose labouring activities help to improve land rent be compensated or should all land rent be given back to society?

Richard T. Ely, a pioneering institutional economist, sought to provide new answers to these questions. He did so by emphasising land, especially redefining land, reintegrating economics and law through land, and bringing in the courts as arbiter to the land rent question. Accordingly, Ely’s focus was not so much on growth, but rather on how land rent is an instrument for creating and maintaining systemic inequality and in what ways inclusive prosperity or wellbeing might be nurtured in an ecologically sound society.

These contributions are of continuing importance. Three reasons help to make the point. The first is that the Revue de la régulation1 is seeking to bring back the rent approach to the political economy of the régulation school at a time when the study of extractivism is at the crossroads on whether to give any place to ‘earlier’ rentier state analysis pioneered by Hossein Mahdavy (see, for example, Mahdavy, 1970).

The second is that the rent approach to the study of inequality has been marginalised in political economy, which is increasingly centred on labour and capital, and their growth (Obeng-Odoom, 2020a; 2021), rather than on land and its place in redistribution (Sheil, 2015; Asongu, 2016). In the USA, Piketty (2014) shows that inequality levels have reached 1910/1920 levels of between 45-50 percent wealth concentration in the hands of the top 10 percent of the population in that country (also, updates in Piketty, 2020). OXFAM (2014) reports that 85 people now have the same wealth as half of the world (3.5bn people). The attempts to explain this inequality has typically focussed on capital and labour. For example, Piketty’s contributions have largely focused on the capital-income ratio (see, for example, Piketty, 2014, p. 8, p. 18, p. 40, p. 42). In general, a careful analysis of land and property rights has largely been ignored, as Robert Rowthorn (2014) pointed out in his review of Piketty’s work for the Cambridge Journal of Economics. Much like Piketty’s work, the OXFAM report focuses on total wealth and the proportion going to the class of capitalists, while others demand attention to labour, but only make superficial or rhetorical comments about land-based inequality.

A third and final reason for the continuing importance of Ely’s contribution is that he has been overlooked as an institutionalist.

Ely gradually disappeared from American social sciences after the early twentieth century […] neoclassical thought […] made every effort to limit his place in the history of thought, granting him only a few mundane lines in the New Palgrave. (Rocca, 2020, p. 11)

Institutionalism is well developed in modern political economics, but its relationship to land and property rights especially as echoed in the work of Richard Theodore Ely, is poorly understood. The entries on ‘institutionalism’ in the Encyclopedia of Political Economy make no reference to Ely (see Waller, 2001, p. 523-528; O’Hara & Waller, 2001, p. 528-532; Hutton, 2001, p. 532-535; Hodgson, 2001, p. 535-538), although he is the “progenitor” of institutional political economy (Vaughn, 1994, p. 28), “founder of land economics” (Weimer, 1984; Malpezzi, 2009), “dean of American economists” (Vaughn, 2000, p. 239) and the founding editor of the field’s pre-eminent journal, Land Economics, initially called the Journal of Land and Public Utility Economics (Salter, 1942).

The existing work on Ely is so little that it can easily be summarised. One type is biographical, looking at the life and contribution of Ely (see, for example, Rocca, 2020). Another is laudatory of his proposals, while the third is entirely dismissive of the political proposals of Ely about war, and unions, for example (see a review in Bradizza, 2013, p. 13-16). Bradizza’s (2013) book and Rocca’s (2020) book chapter are some of the rare recent contributions on Ely seminal interventions on property rights, but these studies do not address Ely’s surplus approach to rent. It seems Ely’s work on rent has largely been forgotten.

Demonstrating the continuing importance of Ely, I draw on his original books and papers, along with existing wider analyses of his work, including reviews of his books published around the time his books were first released. In doing so, in this paper I seek to explain and evaluate Ely’s distinctive approach to rent and to reflect on its significance in modern institutional economics and political economy more widely at the time of a resurgence in extractivism and rentierism.

Like other surplus theorists, Ely rejected the income approach to rent common in neoclassical economics. However, unlike other surplus theorists, Ely recognised that landowners bear substantial costs, so not all the rents going to them should be socialised. He contended that the rent going to landlords was justified so long as they put their private property to social uses. If they failed to do so and, hence, inequality continued to increase or remained entrenched, again Ely broke ranks with other surplus theorists by refraining from the use of revolutionary political processes. Instead, he preferred evolutionary transformation in the form of changes in laws and, notably, appeal to the courts to intervene in addressing growing inequalities. This emphasis on law and rules also distinguishes Ely’s approach to land, which other surplus theorists considered as a unity. For Ely, land was not only a ‘bundle of sticks’ with diverse interests and tenures; land rent also differs based on use, type of land, and change of use and land type, along with all the typical surplus approach emphasis on, say, location and fertility (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, p. 80-81). In this sense, like Marx’s theories of rent (Munro, 2022), Ely’s surplus approach is historically specific, against absolutism, and crude determinism (Rocca, 2020, p. 4). However, unlike Marx’s theorising, Ely’s approach was evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, and his ‘bundle of sticks’ approach, far more granular. In general, Ely’s specific surplus approach created a “Golden mean”, with three defining features (Rocca, 2020, p. 3), namely: offering a critique of the status quo, providing the principles undergirding evolutionary alternatives, and providing concrete practical steps or policies for creating an inclusive society.

Ely contemplated the limits of his surplus approach. For instance, he suggested that if the courts failed, new judges could be appointed. Concurrently, commissions of enquiry could be established and used to pursue reform (Rocca, 2020, p. 9). However, he was less successful in foreseeing the tendency for property rights to entrench inequality and how that inequality itself gives power over the courts. Also, he overlooked the various ways in which the courts are stratified and racialized. The difficulties of simply appointing new judges in such a racialised environment was not carefully analyzed either. More fundamentally, Ely paradoxically endorsed the global intersections of national inequalities, and entrenched stratification.

To flesh out these arguments, the rest of the paper is divided into three sections. Rent and surplus explains Ely’s conceptualization of rent, stressing how it differs from other theorizations of rent. Rent and distribution discusses how Ely’s surplus approach to rent is applied in the analysis of property and maldistribution. Critiques and contradictions shows the limitations of Ely’s approach.

2. Rent and Surplus

Rent features prominently in Ely’s political economy. While many political economists equate rent and surplus, Ely considered some, but not all, rent to be surplus. In his article, “land income” (Ely, 1928), he clarified how his three-part contribution relates to neoclassical economics, classical economics, and institutional economics. For both neoclassical and classical economics, he offered critiques, paving the way for his attempt to make a positive contribution to institutional economics.

Neoclassical economics regards rent as a payment for the use of land, itself a gift of nature whose value is determined through the interaction of supply and demand. According to Ely, none of these is accurate (Ely, 1928, p. 409). Ely (1917, p. 20, p. 28; 1928) considered rent to be payment for more than land use. Rent reflects privilege for the use of a multiplicity of property rights in land, which is itself made up of several rights together, not a unity. Ely was one of the early exponents of the notion that property is a ‘bundle of rights’ (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, p. 80-81), not the singular view of property so commonly held in neoclassical economics. This emphasis on rights and economics also made Ely a pioneer of the economics approach to law or the law approach to economics, the combination of which is much bigger than the total of the various parts. For instance, the ‘bundle of rights’ metaphor for Ely also signified an evolutionary approach to social inclusion, not simply a meme of laws and rights (Rocca, 2020, p. 7). In Ely’s political economy of rent, therefore, the courts are clearly central in settling questions of rent and social injustice. In neoclassical economics, too, property rights need to be guaranteed by the courts of law, but in the case of Ely, “they are not absolute rights of an abstract or isolated individual but social arrangements to be justified because they serve definite social-economic ends” (Cohen, 1917, p. 388). The courts in Ely’s surplus approach do not simply favour the landlord, but they consider the social good of private property.

Ely’s approach differs from other surplus approaches, at least in three respects. Firstly, land is not a free resource of nature. Secondly, not all rent is surplus. Thirdly, although contingent rather than categorical, Ely’s proposed solution to the surplus problem is to be found in the courts. Explaining these three differences is crucial for appreciating the essence of Ely’s surplus approach. Starting with whether land is free for Ely is fundamental. Unlike in the classical economics tradition of surplus value which considers that land is a gift, neither land nor land-use is free in Ely’s surplus approach to rent. There are waiting and ripening costs to be borne by the user of land. For these reasons, land income, Ely’s preferred expression for land rent, is not simply the product of supply and demand. He recognises location advantages, the role of public investments, luck, and uncertainty in determining rent, but how they influence rent is shaped by both land-use type, land-use form, and the change between land uses, ranging from mineral land, agricultural land, urban land, and forest land, to many other types of land (Ely, 1922, p. 39-42; 1928).

The second difference between Ely’s approach and other surplus approaches relates to whether all rent is ‘surplus’ (Ely, 1914, p. 400-411). In many of the surplus approaches, rent is an extra payment received over and above what non-privileged people receive; or rent is the extra payment received over subsistence levels. Alternatively, rent could be seen as anything that is owed to labour after it has been paid an exploitation wage. There is also rent as “economic surplus”, which Ely considers the most similar to his approach. According to him, this rent or economic surplus is the “excess over and above what is required to secure the application of the requisites of production” (Ely, 1914, p. 401). What sets Ely apart is that his reading of ‘surplus’ was unlike most classicals who contended that any payment that exceeds what is socially necessary for the factor of production to be used is to be considered as rent or surplus. Karl Marx used ‘surplus value’ to denote anything in excess of what is paid to labour. Henry George, on the other hand, generally considered all land income to be unearned increment and, hence, postulated that the annualised rental value of land should be taxed away, while removing taxes on labour and capital.

Ely’s proposed solution to rent-based problems also set his approach apart from other surplus frameworks. Ely recognised that privilege and interests, even insider group-trading and information can pave the way for extraordinary advantages to accrue to individual landlords. That is, that society creates the conditions for rent. He called this influence of group characteristics a “‘group relationship’ theory of land income” (Ely, 1928, p. 421, italics added). However, he maintained that the broad-based surplus approach is problematic. It is not the privileges per se that generate the increases in value, but the public facilities. However, even these so-called ‘unearned’ incomes are earned because individual landlords incur costs. Ely points to waiting costs and ripening costs as examples (Ely, 1928, p. 409-414). Accordingly, he contended that landlords must be compensated for the cost of waiting and of deferring the use of land to a future date.

To the charge that speculative investments should be discouraged, Ely argued that such speculation is justified because often land investors need to acquire adjoining parcels of land, if they consider that other uses to which such lots could be used would hamper the realisation of the full potential of the land. So, speculation is socially necessary (Ely, 1928, p. 414-416). Ely also argued that land can suffer decrements. If rents can increase, they can also fall. In Ely’s expression, there are both “unearned increments and likewise unearned decrements” (Ely, 1928, p. 426). For all these risks, landlords should not be assumed to always benefit from “unearned income”. “It is suggestive of serious mistakes”, wrote Ely, “that the consideration of land rent and land income has not been closely connected with the consideration of costs. […] The classical view of the rent of land is that it is income without cost” (Ely, 1922, p. 33).

Still, Ely’s approach to rent is based on the surplus approach in a narrower sense. In Outlines of Land Economics, under “Definition of surplus used in this work”, Ely wrote, “The economic surplus is that which is paid over and above such a return to those who are engaged in production as will induce them to do their part fully and efficiently in the work of production” (Ely, 1922, p. 23). Of the five forms of surplus, Ely names “rent of land” as the first, the rest being interest, personal surplus, monopoly gains, and gains of conjecture (Ely, 1922, p. 26). Contrary to the classicals, Ely makes a distinction between surplus and socially useful surplus. The latter is surplus which, when taken back from rent via tax (for example), the land investors will be so demoralised that they give less than optimal contribution to land investment (Ely, 1922, p. 26-27).

Finally, Ely’s preference is to use the courts to address problems of surplus and rent. However, unlike others who were more categorical about such claims, Ely insisted that his position of rent was not cast in stone. Rent was one of the fields of research he set out in his course about, and vision of, land economics (Ely, 1917, p. 28-29). There were three aspects in these endeavours: Description, Definition, and Determination of the claims about rent. In terms of description, he argued that the field of land economics should focus on evolutionary changes in the use of the terms, to analyse the significance in the use of the term and to evaluate how rent is used both in science and in the market. In terms of Definition, he insisted on rent as power or privileged position. Both of these percolate his third charge: to offer empirical assessments of rental theories continuously (including the effects of custom and competition on rent). Reflecting the influence of the German Historical School on Ely (Rocca, 2020, p. 2), his surplus approach is historically specific, against determinism, and absolutism. These features also Ely’s approach to extractivism and distribution.

3. Rent, Extractivism, and Distribution

To examine how Ely’s surplus approach is applied to the analysis of extractivism, structural or long-term inequality, examining his book, Property and Contract in Their Relations to the Distribution of Wealth (hereafter Property and Contract, Ely, 1914) is critical because of its use of “wealth” as “weal” or “that which produced well-being” (Ely, 1914, p. 19) – a central issue in the analysis of global social problems about extractivism. Wealth, as a concept has many intertwined aspects, namely: economic wealth and social wealth. Private wealth, Ely explains, “means economic goods which yield utilities to the individual, and it may even mean something which detracts from social wealth”. Even though private wealth includes “legitimate and proper claims on others”, private wealth “is a concept which belongs primarily to a discussion of individual distribution, while social wealth is a concept which receives special emphasis in production” (Ely, 1914, p. 23). Public and social wealth may be similar (e.g., a post office), but not all public (state) wealth is social wealth.

It is from this formulation that Ely develops his approach to distribution. In Property and Contract (Ely, 1914), he sets out to build on this formulation. In doing so, he argues that distribution is more about ownership than location. While Ely’s questions such as “in whose hand do they rest as property?”, that is “who has the right to consume them, to sell them, to give them away?” (Ely, 1914, p. 1) have a Marxian ring, his question: what are the “underlying economic institutions upon which the economic structure rests” (Ely, 1914, p. 5), takes the analysis one step beyond the Marxist ‘structuralist’ perspective.

Ely’s approach to the study of inequality is based on three questions. First, what is the distribution of income and wealth among ‘the various units of the social organism?’ (Ely, 1914, p. 2). Next, what portion of this wealth produced is derived from or given back to land, labour, capital, or entrepreneurship? Then, what institutions support the present economic structure? Marxists typically leave their analysis at the second level in the enquiry, while for Ely, the third aspect constitutes the ‘fundamental’ issue: “The third line of enquiry […] is concerned with the underlying economic institutions upon which our whole economic structure rests. The fundamentals have been much neglected […]” (Ely, 1914, p. 5). On page 6, Ely also equates institutions with “foundation”. Figure 1 is a schematic presentation of Ely’s approach.

Figure 1. Ely’s approach to analysing the distribution of wealth

Figure 1 is an annotated diagram of Ely’s analysis of distribution. The institutions in the figure are the fundamentals of the system. They come in the form of collective social forces that consciously or unconsciously shape inequality. Unconscious social forces are those that are not directed at distribution per se (e.g., some laws) but end up having an impact on the question of distribution (e.g., through the unequal application of these laws). The self-conscious forces, called “social self-consciousness”, are rather different. They are aimed at affecting the question of distribution. They may come in the form of legislation, action (judicial, police, executive/government), and public opinion (through praise, criticism, punishment, and reward). Social self-consciousness can also come in the form of social and interest group activity that lobby to change the distribution of incomes and wealth. Such lobby groups can be associations, labour organisations, consumer leagues, and religious groups. There is a relationship between the social self-conscious and the unconscious social forces in the sense that the unconscious may become affected by the conscious with the effluxion of time just as the conscious may evolve into unconscious forces with time.

Individuals are not regarded as institutions in Ely’s approach, but their actions interact with institutions. Individual actions can be conscious, or individuals can unconsciously shape their proportion of wealth. Conscious actions such as planning and training may improve the individual’s proportion of income and wealth. Unconscious actions such as being disciplined, staying out of trouble, and study that is not aimed at improving the individual proportion of incomes and wealth may all contribute to a bigger stake in incomes. However, whether conscious or unconscious, such individual actions interact with institutions such as the media (Ely, 1914). Overall, it is the interaction of all these factors that shapes the distribution of income and wealth. As Ely notes:

We have the incomes which come to us partly because we work for them, in part also we have them because society has decided that we should have them, and not infrequently we have them because certain social forces, operating more or less unconsciously, have cooperated with our own efforts to secure them, or have even procured them for us without any efforts on our part. (Ely, 1914, p. 14)

Institutions, then, are the key forces for Ely. The institution of inheritance and the movement of property values are given by Ely as classic examples of what society does for us in terms of getting a proportion of the incomes and wealth. These considerations lead to the question of how institutions are formed. For Ely, they are collectively created, not individually devised. In his own words: “Passing over to an examination of the fundamentals in the existing socio-economic order, the first truth to note is that they are established not by individuals, nor by nature, but by human society” (Ely, 1914, p. 16).

While institutions are crucial in this approach, it does not mean that institutions themselves are built by individual action. Institutional analysis consciously veers away from beginning with individual characteristics, not only because it is institutions that matter but also because individual actions have been constrained/enabled/influenced by institutions over time and they are still being moulded by institutions. Of all the institutions of analysis, however, Ely centres his case on property, especially private property. In his own words: “The first fundamental institution in the distribution of wealth is the sphere of private property” (Ely, 1914, p. 58, capitalization in original quotation removed).

To illustrate this point, consider oil extractivism, rentierism, or (re)primarisation. A range of scholars and activists and scholar-activists reduce the process to mere extraction of oil in which case every extraction of oil is extractivism and hence, the demand to leave oil in the ground (Obeng-Odoom, 2014, p. 33-36). Others, notably Marxist scholars, consider extractivism as linked to the system of transnational extraction of oil (Nwoke, 1984a, 1984b; Cooney, 2016; Barkin, 2017; Cooney & Freslon, 2019). Thus, the ownership structure along with the international division of labour in which the Global South is consigned the role of raw oil production and the Global North supplies the tools needed to do the extraction and processing are all extractivist, meaning they come with little or no structural transformation in the economy, for example, through local-centred industrialisation. In this sense, colonialism was an extractivist regime because it transferred oil rents from the Global South to the Global North by disinvesting in oil and other infrastructure to ensure socio-economic transformation of oil economies. With the growing power of transnational corporations, Marxists argued that it would be impossible to bargain with them (see Nwoke, 1984b). In this respect, since it is difficult to bargain with transnational-colonial-imperial state complex for rent, Marxists advocated the nationalisation of oil resources. This highly influential position inspired many postcolonial oil economies to create national oil companies to socialise the rents from oil. Examples of such national oil companies are Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia and, until recently, Mexico (Sarbu, 2014, p. xii, p. 35). Yet, as is now well known, even when oil wells have been nationalised, oil institutions have still transferred resources into the hands of private entities.

Perhaps, the issue is not so much capital, or not solely capital, industrialisation, and state based-growth, it is also land, wider socio-ecological transformation, and inclusive change (Ely et al., 1917, p. 3-18). “Conservation policies are then land policies” (Ely et al., 1917, p. 54). “Conservation means three things: viz (1) Maintenance as far as possible; (2) Improvement where possible; (3) Justice in distribution” (Ely et al., 1917, p. 3). Ely points to a tendency for concentration through private property rights (Ely et al., 1917, p. 60-69). “Conservation is considered […] to show that it is first of all a problem of property relation” (Ely et al., 1917, p. 3). Yet, ‘property’ is a poorly understood concept. Even in property economics – supposedly the centre for the study of the economics of property – ‘property’ is confusingly regarded as a ‘thing’, often real estate and ‘possession’ of property confused with the ‘ownership’ of property (cf. Steiger, 2006; Griethuysen van, 2012). Property rights analysts add a layer of ‘rights’ to explain ‘property’ by demanding that property be regarded as a ‘bundle of rights’ exercised over a thing, often real estate and land.

Ely also uses the ‘bundle of rights’ metaphor (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, p. 80-81), but he shifts the emphasis from property relations to social relations. According to him: “the essence of property is in the relations among men arising out of their relations to things” (Ely, 1914, p. 96). For the purpose of rent theories, Ely’s focus suggests a double shift, first from individuals to property and, second, from property to society. Therefore, property, connotes class, status, and position. Property is not merely individuals having a bundle of rights, individuals exercising certain rights over things, or “the category of legal doctrines concerned with allocating rights to material resources”, as legal and new institutional economics perspectives hold (Alexander & Peñalver, 2012, p. 6). If property implies class, subclasses and inter-group differences, then so does rent: its payments could vary according to group position and its very existence is a spark for and maintains inequality and social stratification in an environment in which different groups pay different types of rent. In this sense, Ely delves into the workings of property, notably its (a) characteristics (b) mode of transfer, and (c) how it is established among various groups.

Ely refers to the ‘sphere’ of private property. This notion connotes two main features of property: its extensivity and intensivity. The extensivity of private property refers to how widespread is property which is individually owned. Intensivity refers to how many sticks are in the ‘bundle of rights’ (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, p. 80-81). Therefore, to consider property, the analyst must dig into both the breadth (extensivity) and depth (intensivity) of private property. Ely also recognises other types of tenure, namely public property (exercised by a political unit such as a city or a nation-state) and common property (exercised by a social grouping such as a community). While Ely’s attention is centred on private property, to investigate property as a driver of inequality, all types must be analysed. In doing so, the conditions under which property is held, the laws about the transfer of property (e.g., taxation or no taxation; extensive or limited transfer taxes), and the evolution of property in both its intensivity and extensivity must be studied. Property itself may be classified as ‘subjects’ (classification according to actors) and ‘objects’ (classification according to objects over which rights are exercised). Property subjects may be classified into common, private, and public property, while property objects may be human beings, land, and capital (Ely, 1914, chap. 10, book 2). It is also possible to classify property according to duration (e.g., freehold). That being said, Ely points to the crucial test of being in the propertied class: ownership as distinct from possession. Mere possession of property does not confer ‘property’ class status. According to Ely, this is why anarchists have strongly advocated that tenants in possession would rather have their possession commuted to ownership (Ely, 1914, chap. 4, book 2). Ownership confers the right of exclusivity, alienation, and appropriation (Ely, 1914, chap. 5, book 2), while possession does not necessarily confer these property rights. Applying his approach to the distribution of wealth as it relates to property and property rights in the twenty-first century illustrates the point further.

Figure 2. Key argument about the tendency under the social theory of property

The process of growing rent itself is disempowering for the poor because they are forced to move away from central areas to the margins. For some landlords, the process of concentrating property rights works through the advance of risky loans. In this process, there is much dispossession aided by both state and market rules interacting with customs and mores. Two examples of how this works are the non-application of land taxation and the removal of all taxes that constitute a brake on the private acquisition of land.

This argument and the approach on which it is based is substantially different from neoclassical or new institutional economics (mainstream economics in this paper) typically based on general equilibrium analysis and Kuznets’ ideas of inequality (see an extensive review by Asongu, 2016). For mainstream economists, inequality is not necessarily considered to be bad because it can be an incentive to hard work. Second, inequality is the result of individual effort or sloth such that the difference between the incomes and wealth can be attributed to hard work or laziness. Otherwise, in general, inequality tends towards disappearance in the form of a spatial equilibrium. The neoclassical approach to the study of wealth and income concentrates largely on the economic aspects of wealth, not its social aspects.