Archive

Wealth and Income Distribution: New Theories Needed for a New Era

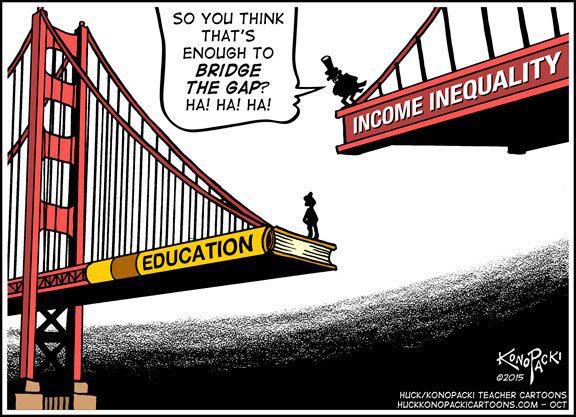

Growth theories traditionally focus on the Kaldor-Kuznets stylised facts. Ravi Kanbur and Nobelist Joe Stiglitz argue that these no longer hold; new theory is needed. The new models need to drop competitive marginal productivity theories of factor returns in favour of rent-generating mechanism and wealth inequality by focusing on the ‘rules of the game.’ They also must model interactions among physical, financial, and human capital that influence the level and evolution of inequality. A third key component will be to capture mechanisms that transmit inequality from generation to generation.

Six decades ago, Nicholas Kaldor (1957) put forward a set of stylized facts on growth and distribution for mature industrial economies. The first and most prominent of these was the constancy of the share of capital relative to that of wealth in national income. At about the same time, Simon Kuznets (1955) put forward a second set of stylized facts — that while the interpersonal inequality of income distribution might increase in the early stages of development, it declines as industrialized economies mature.

These empirical formulations brought forth a generation of growth and development theories whose object was to explain the stylised facts. Kaldor himself presented a growth model which claimed to produce outcomes consistent with constancy of factor shares, as did Robert Solow. Kuznets also developed a model of rural-urban transition consistent with his prediction, as did many others (Kanbur 2012).

Kaldor-Kuznets Facts No Longer Hold

However, the Kaldor-Kuznets stylized facts no longer hold for advanced economies. The share of capital as conventionally measured has been on the rise, as has interpersonal inequality of income and wealth. Of course, there are variations and subtleties of data and interpretation, and the pattern is not uniform. But these are the stylized facts of our time. Bringing these facts centre stage has been the achievement of research leading up to Piketty (2014).

It stands to reason that theories developed to explain constancy of factor shares cannot explain a rising share of capital. The theories developed to explain the earlier stylized facts cannot very easily explain the new trends, or the turnaround. At the same time, rising inequality has opened once again a set of questions on the normative significance of inequality of outcomes versus inequality of opportunity. New theoretical developments are needed for positive and normative analysis in this new era.

What sort of new theories? In the realm of positive analysis, Piketty has himself put forward a theory based on the empirical observation that the rate of return to capital, r, systematically exceeds the rate of growth, g; the famous r > g relation. Much of the commentary on Piketty’s facts and theorizing has tried to make the stylized fact of rising share of capital consistent with a standard production function F (K, L) with capital ‘K’ and labour ‘L’. But in this framework a rising share of capital can be consistent with the other stylised fact of rising capital-output ratio only if the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour is greater than unity, which is not consistent with the broad empirical findings (Stiglitz, 2014a). Further, what Piketty and others measure as wealth ‘W’ is a measure of control over resources, not a measure of capital K, in the sense that that is used in the context of a production function.

Differences between K and W

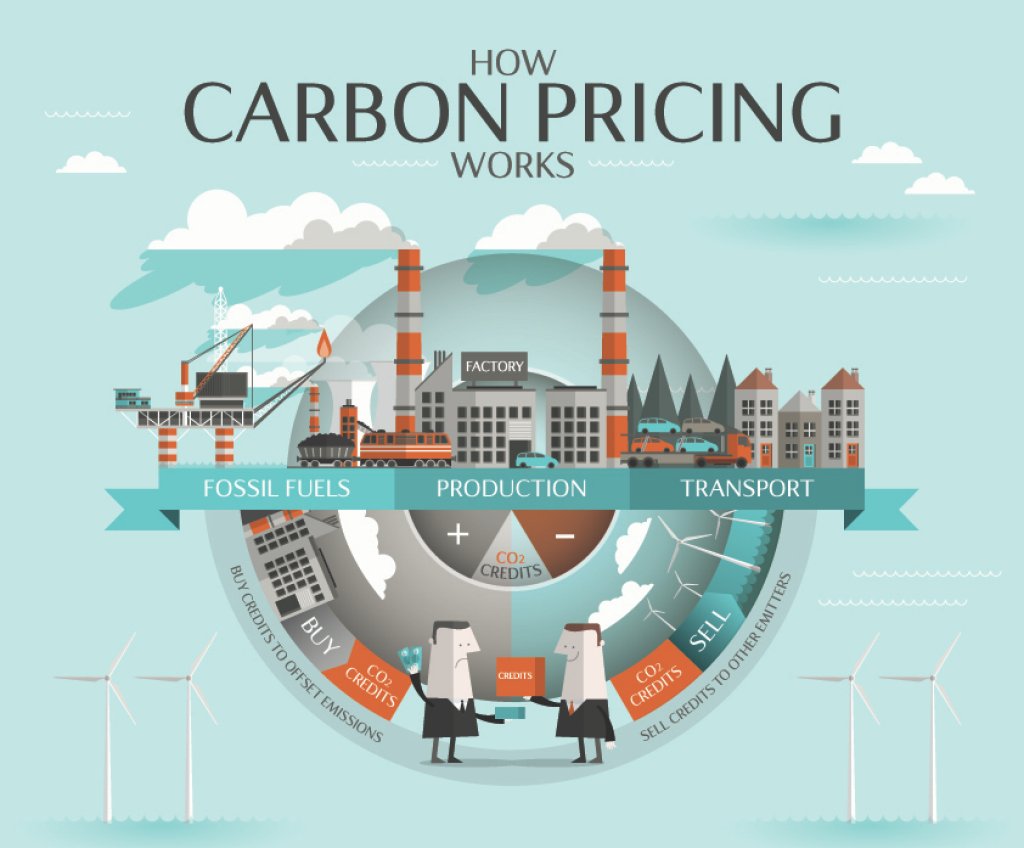

There is a fundamental distinction between capital K, thought of as physical inputs to production, and wealth W, thought of as including land and the capitalized value of other rents which give command over purchasing power. This distinction will be crucial in any theorizing to explain the new stylized facts. ‘K’ can be going down even as ‘W’ increases; and some increases in W may actually lower economic productivity. In particular, new theories explaining the evolution of inequality will have to address directly changes in rents and their capitalized value (Stiglitz 2014). Two examples will illustrate what we have in mind.

- Consider first the case of all sea-front property on the French Riviera.

As demand for these properties rises, perhaps from rich foreigners seeking a refuge for their funds, the value of sea frontage will be bid up. The current owners will get rents from their ownership of this fixed factor. Their wealth will go up and their ability to command purchasing power in the economy will rise correspondingly. But the actual physical input to production has not increased. All else constant, national output will not rise; there will only be a pure distributional effect.

- Consider the case where the government gives an implicit guarantee to bail out banks.

This contingent support to income flows from ownership of bank shares will be capitalised into the value of these shares. Of course, there is an equal and opposite contingent liability on all others in the economy, in particular on workers — the owners of human capital. Again, without any necessary impact on total output, the political economy has created rents for share owners, and the increase in their wealth will be reflected in rising inequality. One can see this without going through a conventional production function analysis. Of course, the rents once created will provide further resources for rentiers to lobby the political system to maintain and further increase rents. This will set in motion a spiral of increasing inequality, which again does not go through the production system at all — except to the extent that the associated distortions represent a downward shift in the productivity of the economy (at any level of inputs of ‘K’ and labour).

Analysing the role of land rents in increases in inequality can be done in a variant of standard neoclassical models — by expanding inputs to include land; but explaining increase in inequality as a result of an increase in other forms of rent will need a theory of rents which takes us beyond the competitive determination of factor rewards.

Differences in Inequality: Capital Income versus Labour Income

The translation from factor shares to interpersonal inequality has usually been made through the assumption that capital income is more unequally distributed than labour income. Inequality of capital ownership then translates into inequality of capital income, while inequality of income from labour is assumed to be much smaller. The assumption is made in its starkest form in models where there are owners of capital who save and workers who do not.

These stylised assumptions no longer provide a fully satisfactory explanation of income inequality because: (i) there is more widespread ownership of wealth through life cycle savings in various forms including pensions; and (ii) increasingly unequal returns to increasingly unequally distributed human capital has led to sharply rising inequality of labour income.

Sharply rising inequality of labour income focuses attention on inequality of human capital in its most general sense:

- Starting with unequal prenatal development of the foetus;

- Followed by unequal early childhood development and investments by parents;

- Unequal educational investments by parents and society; and

- Unequal returns to human capital because of discrimination at one end and use of parental connections in the job market at the other end.

Discrimination continues to play a role, not only in the determination of factor returns given the ownership of assets, including human capital; but also on the distribution of asset ownership.

- At each step, inequality of parental resources is translated into inequality of children’s outcomes.

An exploration of this type of inequality requires a different type of empirical and theoretical analysis from the conventional macro-level analysis of production functions and factor shares (Heckman and Mosso, 2014, Stiglitz, 2015).

In particular, intergenerational transmission of inequality is more than simple inheritance of physical and financial wealth. Layered upon genetic inequalities are the inequalities of parental resources. Income inequality across parents, due to inequality of income from physical and financial capital on the one hand, and inequality due to inequality of human capital on the other, is translated into inequality of financial and human capital of the next generation. Human capital inequality perpetuates itself through intergenerational transmission just as wealth inequality caused by politically created rents perpetuates itself.

Given such transmission across generations, it can be shown that the long-run, ‘dynastic’ inequality will also be higher (Kanbur and Stiglitz 2015). Although there have been advances in recent years, we still need fully developed theories of how the different mechanisms interact with each other to explain the dramatic rises in interpersonal inequality in advanced economies in the last three decades.1

High Inequality: New Realities and Old Debates

The new realities of high inequality have revived old debates on policy interventions and their ethical and economic rationale (Stiglitz 2012). Standard analysis which balances the tradeoff between efficiency and equity would suggest that taxation should now become more progressive to balance the greater inherent inequality against the incentive effects of progressive taxation (Kanbur and Tuomala,1994 ).

One counter argument is that what matters is not inequality of ‘outcome’ but inequality of ‘opportunity’. According to this argument, so long as the prospects are the same for all children, the inequality of income across parents should not matter ethically. What we should aim for is equality of opportunity, not income equality. However, when income inequality across parents translates into inequality of prospects across children, even starting in the womb, then the distinction between opportunity and income begins to fade and the case for progressive taxation is not undermined by the ‘equality of opportunity’ objective (Kanbur and Wagstaff 2015).

Concluding Remarks

Thus, the new stylised facts of our era demand new theories of income distribution.

- First, we need to break away from competitive marginal productivity theories of factor returns and model mechanisms which generate rents with consequences for wealth inequality.

This will entail a greater focus on the ‘rules of the game.’ (Stiglitz et al 2015).

- Second, we need to focus on the interaction between income from physical and financial capital and income from human capital in determining snapshot inequality, but also in determining the intergenerational transmission of inequality.

- Third, we need to further develop normative theories of equity which can address mechanisms of inequality transmission from generation to generation.2

References

Bevan, D and J E Stiglitz (1979), “Intergenerational Transfers and Inequality”, The Greek Economic Review, 1(1), August, pp. 8-26.

Heckman, J and S Mosso (2014), “The Economics of Human Development and Social Mobility”, Annual Reviews of Economics, 6: 689-733.

Kaldor, N (1957), “A Model of Economic Growth”, The Economic Journal, 67(268): 591-624.

Kanbur, R (2012), “Does Kuznets Still Matter?” in S. Kochhar (ed.), Policy-Making for Indian Planning: Essays on Contemporary Issues in Honor of Montek S. Ahluwalia, Academic Foundation Press, pp. 115-128, 2012.

Kanbur, R and J E Stiglitz (2015), “Dynastic Inequality, Mobility and Equality of Opportunity“, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 10542.

Kanbur, R and M Tuomala (1994), ‘‘Inherent Inequality and the Optimal Graduation of Marginal Tax Rates”, (with M. Tuomala), Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 96, No. 2, pp. 275-282, 1994.

Kuznets, S (1955), “Economic Growth and Income Inequality”, The American Economic Review, 45(1): 1-28.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Piketty, T, E Saez, and S Stantcheva (2011), “Taxing the 1%: Why the top tax rate could be over 80%”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Roemer, J E and A Trannoy (2014), “Equality of Opportunity”, in A B Atkinson and F Bourguignon (eds.) Handbook of Income Distribution SET Vols 2A-2B. Elsevier.

Stiglitz, J E, et. al. (2015) “Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy“, Roosevelt Institute.

Stiglitz, J E (1969), “Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, Econometrica, 37(3), July, pp. 382-397. (Presented at the December 1966 meetings of the Econometric Society, San Francisco.)

Stiglitz, J E (2012), The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, New York: W.W. Norton.

Stiglitz, J E (2014), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, paper presented to the International Economic Association World Congress, Dead Sea, June and forthcoming in Inequality and Growth: Patterns and Policy, Volume 1: Concepts and Analysis, to be published by Palgrave MacMillan.

Stiglitz, J E (2015), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals: Parts I-IV”, NBER Working Papers 21189-21192, May.

Footnotes

1 For early discussions of such transmission processes, see Stiglitz(1969) and Bevan and Stiglitz (1979).

2 Developments in this area are exemplified by Roemer and Trannoy (2014).

The Surplus Approach to Rent

Theories of rent are wide-ranging. However, whether neoclassical, Marxist, or Proudhonist, they tend to neglect evolutionary institutionalist theorising. Increasingly dominated by the income approach, rent theories need to be expanded, partly to correct existing work, partly to break persistent intellectual monopoly and oligopoly, and particularly to develop institutional theories of rent. In this paper, I attempt to do so by presenting and evaluating the surplus approach to rent, particularly R.T. Ely’s, highlighting its power and potential and stressing its critiques and contradictions. Drawing, among others, on the original writings of Ely, it is argued that, while the emphasis on property rights, land as a ‘bundle of sticks’, and rent as surplus rather than income help to advance heterodox approaches to rent, the surplus approach is severely limited in its analysis of inequalities and how they can be addressed, especially in extractivist and rentier societies. To unravel long-term inequalities that characterize rent and rentier economies, it is crucial for surplus theorists to engage stratification economics which, in turn, can drive the surplus approach to rent.

1. Rent: Beyond Income

Neoclassical economists define rent as the price paid for the use of land obtained in a competitive market (see, for example, O’Sullivan, 2012, p. 157-161). Therefore, rent is an open-market price paid for the use of land – much like interest is income for the use of capital. In this income approach, rent functions as a driver of growth. Also, rent – like price, more generally – becomes a mechanism for allocating land as a scarce resource.

The surplus approach to rent is rather different. Advanced by a wide range of classical and other economists, including the physiocrats, Smithians, Ricardians, Georgists, institutionalists, Marxists and the French Régulationists, rent is not simply the return price for the use of land; it is also surplus (Ely, 1922, 1927; Haila, 1990, 2016; Fine, 2019; Faudot, 2019). Every surplus approach offers a critique of approaches in neoclassical economics and their related policy prescriptions, but the surplus approach also provides a comprehensive and coherent alternative framework to analyse extractivism and other socio-ecological problems (Butler, 2002). In practice, the surplus approach also offers a springboard for developing practical transformative steps and policies to change the world.

Beyond these generalities, the surplus approach has many nuances. Various theorists have debated what land rent is, and what it is not. Many analysts focus on regimes of growth, particularly the French régulationnistes (See, for example, Faudot, 2019, the work of Robert Boyer, and its extensive discussion, including Vercueil, 2016; Harada & Uemura, 2019). When determining how to address inequality, they deal with the question of rent as a surplus, but how to deal with that surplus and whether to emphasise growth or inequalities, land or capital varies widely. Generally, in the surplus approach, a critical question is whether to re-invest the surplus “to expand and transform the existing economic system”, whether the surplus should be ‘wasted in luxury consumption, leading to economic decline’ (Martins, 2018, p. 41), or whether to redistribute the surplus for inclusive economic development. What proportion of land rent should be returned to the landowner? Should a landowner whose labouring activities help to improve land rent be compensated or should all land rent be given back to society?

Richard T. Ely, a pioneering institutional economist, sought to provide new answers to these questions. He did so by emphasising land, especially redefining land, reintegrating economics and law through land, and bringing in the courts as arbiter to the land rent question. Accordingly, Ely’s focus was not so much on growth, but rather on how land rent is an instrument for creating and maintaining systemic inequality and in what ways inclusive prosperity or wellbeing might be nurtured in an ecologically sound society.

These contributions are of continuing importance. Three reasons help to make the point. The first is that the Revue de la régulation1 is seeking to bring back the rent approach to the political economy of the régulation school at a time when the study of extractivism is at the crossroads on whether to give any place to ‘earlier’ rentier state analysis pioneered by Hossein Mahdavy (see, for example, Mahdavy, 1970).

The second is that the rent approach to the study of inequality has been marginalised in political economy, which is increasingly centred on labour and capital, and their growth (Obeng-Odoom, 2020a; 2021), rather than on land and its place in redistribution (Sheil, 2015; Asongu, 2016). In the USA, Piketty (2014) shows that inequality levels have reached 1910/1920 levels of between 45-50 percent wealth concentration in the hands of the top 10 percent of the population in that country (also, updates in Piketty, 2020). OXFAM (2014) reports that 85 people now have the same wealth as half of the world (3.5bn people). The attempts to explain this inequality has typically focussed on capital and labour. For example, Piketty’s contributions have largely focused on the capital-income ratio (see, for example, Piketty, 2014, p. 8, p. 18, p. 40, p. 42). In general, a careful analysis of land and property rights has largely been ignored, as Robert Rowthorn (2014) pointed out in his review of Piketty’s work for the Cambridge Journal of Economics. Much like Piketty’s work, the OXFAM report focuses on total wealth and the proportion going to the class of capitalists, while others demand attention to labour, but only make superficial or rhetorical comments about land-based inequality.

A third and final reason for the continuing importance of Ely’s contribution is that he has been overlooked as an institutionalist.

Ely gradually disappeared from American social sciences after the early twentieth century […] neoclassical thought […] made every effort to limit his place in the history of thought, granting him only a few mundane lines in the New Palgrave. (Rocca, 2020, p. 11)

Institutionalism is well developed in modern political economics, but its relationship to land and property rights especially as echoed in the work of Richard Theodore Ely, is poorly understood. The entries on ‘institutionalism’ in the Encyclopedia of Political Economy make no reference to Ely (see Waller, 2001, p. 523-528; O’Hara & Waller, 2001, p. 528-532; Hutton, 2001, p. 532-535; Hodgson, 2001, p. 535-538), although he is the “progenitor” of institutional political economy (Vaughn, 1994, p. 28), “founder of land economics” (Weimer, 1984; Malpezzi, 2009), “dean of American economists” (Vaughn, 2000, p. 239) and the founding editor of the field’s pre-eminent journal, Land Economics, initially called the Journal of Land and Public Utility Economics (Salter, 1942).

The existing work on Ely is so little that it can easily be summarised. One type is biographical, looking at the life and contribution of Ely (see, for example, Rocca, 2020). Another is laudatory of his proposals, while the third is entirely dismissive of the political proposals of Ely about war, and unions, for example (see a review in Bradizza, 2013, p. 13-16). Bradizza’s (2013) book and Rocca’s (2020) book chapter are some of the rare recent contributions on Ely seminal interventions on property rights, but these studies do not address Ely’s surplus approach to rent. It seems Ely’s work on rent has largely been forgotten.

Demonstrating the continuing importance of Ely, I draw on his original books and papers, along with existing wider analyses of his work, including reviews of his books published around the time his books were first released. In doing so, in this paper I seek to explain and evaluate Ely’s distinctive approach to rent and to reflect on its significance in modern institutional economics and political economy more widely at the time of a resurgence in extractivism and rentierism.

Like other surplus theorists, Ely rejected the income approach to rent common in neoclassical economics. However, unlike other surplus theorists, Ely recognised that landowners bear substantial costs, so not all the rents going to them should be socialised. He contended that the rent going to landlords was justified so long as they put their private property to social uses. If they failed to do so and, hence, inequality continued to increase or remained entrenched, again Ely broke ranks with other surplus theorists by refraining from the use of revolutionary political processes. Instead, he preferred evolutionary transformation in the form of changes in laws and, notably, appeal to the courts to intervene in addressing growing inequalities. This emphasis on law and rules also distinguishes Ely’s approach to land, which other surplus theorists considered as a unity. For Ely, land was not only a ‘bundle of sticks’ with diverse interests and tenures; land rent also differs based on use, type of land, and change of use and land type, along with all the typical surplus approach emphasis on, say, location and fertility (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, p. 80-81). In this sense, like Marx’s theories of rent (Munro, 2022), Ely’s surplus approach is historically specific, against absolutism, and crude determinism (Rocca, 2020, p. 4). However, unlike Marx’s theorising, Ely’s approach was evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, and his ‘bundle of sticks’ approach, far more granular. In general, Ely’s specific surplus approach created a “Golden mean”, with three defining features (Rocca, 2020, p. 3), namely: offering a critique of the status quo, providing the principles undergirding evolutionary alternatives, and providing concrete practical steps or policies for creating an inclusive society.

Ely contemplated the limits of his surplus approach. For instance, he suggested that if the courts failed, new judges could be appointed. Concurrently, commissions of enquiry could be established and used to pursue reform (Rocca, 2020, p. 9). However, he was less successful in foreseeing the tendency for property rights to entrench inequality and how that inequality itself gives power over the courts. Also, he overlooked the various ways in which the courts are stratified and racialized. The difficulties of simply appointing new judges in such a racialised environment was not carefully analyzed either. More fundamentally, Ely paradoxically endorsed the global intersections of national inequalities, and entrenched stratification.

To flesh out these arguments, the rest of the paper is divided into three sections. Rent and surplus explains Ely’s conceptualization of rent, stressing how it differs from other theorizations of rent. Rent and distribution discusses how Ely’s surplus approach to rent is applied in the analysis of property and maldistribution. Critiques and contradictions shows the limitations of Ely’s approach.

2. Rent and Surplus

Rent features prominently in Ely’s political economy. While many political economists equate rent and surplus, Ely considered some, but not all, rent to be surplus. In his article, “land income” (Ely, 1928), he clarified how his three-part contribution relates to neoclassical economics, classical economics, and institutional economics. For both neoclassical and classical economics, he offered critiques, paving the way for his attempt to make a positive contribution to institutional economics.

Neoclassical economics regards rent as a payment for the use of land, itself a gift of nature whose value is determined through the interaction of supply and demand. According to Ely, none of these is accurate (Ely, 1928, p. 409). Ely (1917, p. 20, p. 28; 1928) considered rent to be payment for more than land use. Rent reflects privilege for the use of a multiplicity of property rights in land, which is itself made up of several rights together, not a unity. Ely was one of the early exponents of the notion that property is a ‘bundle of rights’ (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, p. 80-81), not the singular view of property so commonly held in neoclassical economics. This emphasis on rights and economics also made Ely a pioneer of the economics approach to law or the law approach to economics, the combination of which is much bigger than the total of the various parts. For instance, the ‘bundle of rights’ metaphor for Ely also signified an evolutionary approach to social inclusion, not simply a meme of laws and rights (Rocca, 2020, p. 7). In Ely’s political economy of rent, therefore, the courts are clearly central in settling questions of rent and social injustice. In neoclassical economics, too, property rights need to be guaranteed by the courts of law, but in the case of Ely, “they are not absolute rights of an abstract or isolated individual but social arrangements to be justified because they serve definite social-economic ends” (Cohen, 1917, p. 388). The courts in Ely’s surplus approach do not simply favour the landlord, but they consider the social good of private property.

Ely’s approach differs from other surplus approaches, at least in three respects. Firstly, land is not a free resource of nature. Secondly, not all rent is surplus. Thirdly, although contingent rather than categorical, Ely’s proposed solution to the surplus problem is to be found in the courts. Explaining these three differences is crucial for appreciating the essence of Ely’s surplus approach. Starting with whether land is free for Ely is fundamental. Unlike in the classical economics tradition of surplus value which considers that land is a gift, neither land nor land-use is free in Ely’s surplus approach to rent. There are waiting and ripening costs to be borne by the user of land. For these reasons, land income, Ely’s preferred expression for land rent, is not simply the product of supply and demand. He recognises location advantages, the role of public investments, luck, and uncertainty in determining rent, but how they influence rent is shaped by both land-use type, land-use form, and the change between land uses, ranging from mineral land, agricultural land, urban land, and forest land, to many other types of land (Ely, 1922, p. 39-42; 1928).

The second difference between Ely’s approach and other surplus approaches relates to whether all rent is ‘surplus’ (Ely, 1914, p. 400-411). In many of the surplus approaches, rent is an extra payment received over and above what non-privileged people receive; or rent is the extra payment received over subsistence levels. Alternatively, rent could be seen as anything that is owed to labour after it has been paid an exploitation wage. There is also rent as “economic surplus”, which Ely considers the most similar to his approach. According to him, this rent or economic surplus is the “excess over and above what is required to secure the application of the requisites of production” (Ely, 1914, p. 401). What sets Ely apart is that his reading of ‘surplus’ was unlike most classicals who contended that any payment that exceeds what is socially necessary for the factor of production to be used is to be considered as rent or surplus. Karl Marx used ‘surplus value’ to denote anything in excess of what is paid to labour. Henry George, on the other hand, generally considered all land income to be unearned increment and, hence, postulated that the annualised rental value of land should be taxed away, while removing taxes on labour and capital.

Ely’s proposed solution to rent-based problems also set his approach apart from other surplus frameworks. Ely recognised that privilege and interests, even insider group-trading and information can pave the way for extraordinary advantages to accrue to individual landlords. That is, that society creates the conditions for rent. He called this influence of group characteristics a “‘group relationship’ theory of land income” (Ely, 1928, p. 421, italics added). However, he maintained that the broad-based surplus approach is problematic. It is not the privileges per se that generate the increases in value, but the public facilities. However, even these so-called ‘unearned’ incomes are earned because individual landlords incur costs. Ely points to waiting costs and ripening costs as examples (Ely, 1928, p. 409-414). Accordingly, he contended that landlords must be compensated for the cost of waiting and of deferring the use of land to a future date.

To the charge that speculative investments should be discouraged, Ely argued that such speculation is justified because often land investors need to acquire adjoining parcels of land, if they consider that other uses to which such lots could be used would hamper the realisation of the full potential of the land. So, speculation is socially necessary (Ely, 1928, p. 414-416). Ely also argued that land can suffer decrements. If rents can increase, they can also fall. In Ely’s expression, there are both “unearned increments and likewise unearned decrements” (Ely, 1928, p. 426). For all these risks, landlords should not be assumed to always benefit from “unearned income”. “It is suggestive of serious mistakes”, wrote Ely, “that the consideration of land rent and land income has not been closely connected with the consideration of costs. […] The classical view of the rent of land is that it is income without cost” (Ely, 1922, p. 33).

Still, Ely’s approach to rent is based on the surplus approach in a narrower sense. In Outlines of Land Economics, under “Definition of surplus used in this work”, Ely wrote, “The economic surplus is that which is paid over and above such a return to those who are engaged in production as will induce them to do their part fully and efficiently in the work of production” (Ely, 1922, p. 23). Of the five forms of surplus, Ely names “rent of land” as the first, the rest being interest, personal surplus, monopoly gains, and gains of conjecture (Ely, 1922, p. 26). Contrary to the classicals, Ely makes a distinction between surplus and socially useful surplus. The latter is surplus which, when taken back from rent via tax (for example), the land investors will be so demoralised that they give less than optimal contribution to land investment (Ely, 1922, p. 26-27).

Finally, Ely’s preference is to use the courts to address problems of surplus and rent. However, unlike others who were more categorical about such claims, Ely insisted that his position of rent was not cast in stone. Rent was one of the fields of research he set out in his course about, and vision of, land economics (Ely, 1917, p. 28-29). There were three aspects in these endeavours: Description, Definition, and Determination of the claims about rent. In terms of description, he argued that the field of land economics should focus on evolutionary changes in the use of the terms, to analyse the significance in the use of the term and to evaluate how rent is used both in science and in the market. In terms of Definition, he insisted on rent as power or privileged position. Both of these percolate his third charge: to offer empirical assessments of rental theories continuously (including the effects of custom and competition on rent). Reflecting the influence of the German Historical School on Ely (Rocca, 2020, p. 2), his surplus approach is historically specific, against determinism, and absolutism. These features also Ely’s approach to extractivism and distribution.

3. Rent, Extractivism, and Distribution

To examine how Ely’s surplus approach is applied to the analysis of extractivism, structural or long-term inequality, examining his book, Property and Contract in Their Relations to the Distribution of Wealth (hereafter Property and Contract, Ely, 1914) is critical because of its use of “wealth” as “weal” or “that which produced well-being” (Ely, 1914, p. 19) – a central issue in the analysis of global social problems about extractivism. Wealth, as a concept has many intertwined aspects, namely: economic wealth and social wealth. Private wealth, Ely explains, “means economic goods which yield utilities to the individual, and it may even mean something which detracts from social wealth”. Even though private wealth includes “legitimate and proper claims on others”, private wealth “is a concept which belongs primarily to a discussion of individual distribution, while social wealth is a concept which receives special emphasis in production” (Ely, 1914, p. 23). Public and social wealth may be similar (e.g., a post office), but not all public (state) wealth is social wealth.

It is from this formulation that Ely develops his approach to distribution. In Property and Contract (Ely, 1914), he sets out to build on this formulation. In doing so, he argues that distribution is more about ownership than location. While Ely’s questions such as “in whose hand do they rest as property?”, that is “who has the right to consume them, to sell them, to give them away?” (Ely, 1914, p. 1) have a Marxian ring, his question: what are the “underlying economic institutions upon which the economic structure rests” (Ely, 1914, p. 5), takes the analysis one step beyond the Marxist ‘structuralist’ perspective.

Ely’s approach to the study of inequality is based on three questions. First, what is the distribution of income and wealth among ‘the various units of the social organism?’ (Ely, 1914, p. 2). Next, what portion of this wealth produced is derived from or given back to land, labour, capital, or entrepreneurship? Then, what institutions support the present economic structure? Marxists typically leave their analysis at the second level in the enquiry, while for Ely, the third aspect constitutes the ‘fundamental’ issue: “The third line of enquiry […] is concerned with the underlying economic institutions upon which our whole economic structure rests. The fundamentals have been much neglected […]” (Ely, 1914, p. 5). On page 6, Ely also equates institutions with “foundation”. Figure 1 is a schematic presentation of Ely’s approach.

Figure 1. Ely’s approach to analysing the distribution of wealth

Figure 1 is an annotated diagram of Ely’s analysis of distribution. The institutions in the figure are the fundamentals of the system. They come in the form of collective social forces that consciously or unconsciously shape inequality. Unconscious social forces are those that are not directed at distribution per se (e.g., some laws) but end up having an impact on the question of distribution (e.g., through the unequal application of these laws). The self-conscious forces, called “social self-consciousness”, are rather different. They are aimed at affecting the question of distribution. They may come in the form of legislation, action (judicial, police, executive/government), and public opinion (through praise, criticism, punishment, and reward). Social self-consciousness can also come in the form of social and interest group activity that lobby to change the distribution of incomes and wealth. Such lobby groups can be associations, labour organisations, consumer leagues, and religious groups. There is a relationship between the social self-conscious and the unconscious social forces in the sense that the unconscious may become affected by the conscious with the effluxion of time just as the conscious may evolve into unconscious forces with time.

Individuals are not regarded as institutions in Ely’s approach, but their actions interact with institutions. Individual actions can be conscious, or individuals can unconsciously shape their proportion of wealth. Conscious actions such as planning and training may improve the individual’s proportion of income and wealth. Unconscious actions such as being disciplined, staying out of trouble, and study that is not aimed at improving the individual proportion of incomes and wealth may all contribute to a bigger stake in incomes. However, whether conscious or unconscious, such individual actions interact with institutions such as the media (Ely, 1914). Overall, it is the interaction of all these factors that shapes the distribution of income and wealth. As Ely notes:

We have the incomes which come to us partly because we work for them, in part also we have them because society has decided that we should have them, and not infrequently we have them because certain social forces, operating more or less unconsciously, have cooperated with our own efforts to secure them, or have even procured them for us without any efforts on our part. (Ely, 1914, p. 14)

Institutions, then, are the key forces for Ely. The institution of inheritance and the movement of property values are given by Ely as classic examples of what society does for us in terms of getting a proportion of the incomes and wealth. These considerations lead to the question of how institutions are formed. For Ely, they are collectively created, not individually devised. In his own words: “Passing over to an examination of the fundamentals in the existing socio-economic order, the first truth to note is that they are established not by individuals, nor by nature, but by human society” (Ely, 1914, p. 16).

While institutions are crucial in this approach, it does not mean that institutions themselves are built by individual action. Institutional analysis consciously veers away from beginning with individual characteristics, not only because it is institutions that matter but also because individual actions have been constrained/enabled/influenced by institutions over time and they are still being moulded by institutions. Of all the institutions of analysis, however, Ely centres his case on property, especially private property. In his own words: “The first fundamental institution in the distribution of wealth is the sphere of private property” (Ely, 1914, p. 58, capitalization in original quotation removed).

To illustrate this point, consider oil extractivism, rentierism, or (re)primarisation. A range of scholars and activists and scholar-activists reduce the process to mere extraction of oil in which case every extraction of oil is extractivism and hence, the demand to leave oil in the ground (Obeng-Odoom, 2014, p. 33-36). Others, notably Marxist scholars, consider extractivism as linked to the system of transnational extraction of oil (Nwoke, 1984a, 1984b; Cooney, 2016; Barkin, 2017; Cooney & Freslon, 2019). Thus, the ownership structure along with the international division of labour in which the Global South is consigned the role of raw oil production and the Global North supplies the tools needed to do the extraction and processing are all extractivist, meaning they come with little or no structural transformation in the economy, for example, through local-centred industrialisation. In this sense, colonialism was an extractivist regime because it transferred oil rents from the Global South to the Global North by disinvesting in oil and other infrastructure to ensure socio-economic transformation of oil economies. With the growing power of transnational corporations, Marxists argued that it would be impossible to bargain with them (see Nwoke, 1984b). In this respect, since it is difficult to bargain with transnational-colonial-imperial state complex for rent, Marxists advocated the nationalisation of oil resources. This highly influential position inspired many postcolonial oil economies to create national oil companies to socialise the rents from oil. Examples of such national oil companies are Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia and, until recently, Mexico (Sarbu, 2014, p. xii, p. 35). Yet, as is now well known, even when oil wells have been nationalised, oil institutions have still transferred resources into the hands of private entities.

Perhaps, the issue is not so much capital, or not solely capital, industrialisation, and state based-growth, it is also land, wider socio-ecological transformation, and inclusive change (Ely et al., 1917, p. 3-18). “Conservation policies are then land policies” (Ely et al., 1917, p. 54). “Conservation means three things: viz (1) Maintenance as far as possible; (2) Improvement where possible; (3) Justice in distribution” (Ely et al., 1917, p. 3). Ely points to a tendency for concentration through private property rights (Ely et al., 1917, p. 60-69). “Conservation is considered […] to show that it is first of all a problem of property relation” (Ely et al., 1917, p. 3). Yet, ‘property’ is a poorly understood concept. Even in property economics – supposedly the centre for the study of the economics of property – ‘property’ is confusingly regarded as a ‘thing’, often real estate and ‘possession’ of property confused with the ‘ownership’ of property (cf. Steiger, 2006; Griethuysen van, 2012). Property rights analysts add a layer of ‘rights’ to explain ‘property’ by demanding that property be regarded as a ‘bundle of rights’ exercised over a thing, often real estate and land.

Ely also uses the ‘bundle of rights’ metaphor (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, p. 80-81), but he shifts the emphasis from property relations to social relations. According to him: “the essence of property is in the relations among men arising out of their relations to things” (Ely, 1914, p. 96). For the purpose of rent theories, Ely’s focus suggests a double shift, first from individuals to property and, second, from property to society. Therefore, property, connotes class, status, and position. Property is not merely individuals having a bundle of rights, individuals exercising certain rights over things, or “the category of legal doctrines concerned with allocating rights to material resources”, as legal and new institutional economics perspectives hold (Alexander & Peñalver, 2012, p. 6). If property implies class, subclasses and inter-group differences, then so does rent: its payments could vary according to group position and its very existence is a spark for and maintains inequality and social stratification in an environment in which different groups pay different types of rent. In this sense, Ely delves into the workings of property, notably its (a) characteristics (b) mode of transfer, and (c) how it is established among various groups.

Ely refers to the ‘sphere’ of private property. This notion connotes two main features of property: its extensivity and intensivity. The extensivity of private property refers to how widespread is property which is individually owned. Intensivity refers to how many sticks are in the ‘bundle of rights’ (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, p. 80-81). Therefore, to consider property, the analyst must dig into both the breadth (extensivity) and depth (intensivity) of private property. Ely also recognises other types of tenure, namely public property (exercised by a political unit such as a city or a nation-state) and common property (exercised by a social grouping such as a community). While Ely’s attention is centred on private property, to investigate property as a driver of inequality, all types must be analysed. In doing so, the conditions under which property is held, the laws about the transfer of property (e.g., taxation or no taxation; extensive or limited transfer taxes), and the evolution of property in both its intensivity and extensivity must be studied. Property itself may be classified as ‘subjects’ (classification according to actors) and ‘objects’ (classification according to objects over which rights are exercised). Property subjects may be classified into common, private, and public property, while property objects may be human beings, land, and capital (Ely, 1914, chap. 10, book 2). It is also possible to classify property according to duration (e.g., freehold). That being said, Ely points to the crucial test of being in the propertied class: ownership as distinct from possession. Mere possession of property does not confer ‘property’ class status. According to Ely, this is why anarchists have strongly advocated that tenants in possession would rather have their possession commuted to ownership (Ely, 1914, chap. 4, book 2). Ownership confers the right of exclusivity, alienation, and appropriation (Ely, 1914, chap. 5, book 2), while possession does not necessarily confer these property rights. Applying his approach to the distribution of wealth as it relates to property and property rights in the twenty-first century illustrates the point further.

Figure 2. Key argument about the tendency under the social theory of property

The process of growing rent itself is disempowering for the poor because they are forced to move away from central areas to the margins. For some landlords, the process of concentrating property rights works through the advance of risky loans. In this process, there is much dispossession aided by both state and market rules interacting with customs and mores. Two examples of how this works are the non-application of land taxation and the removal of all taxes that constitute a brake on the private acquisition of land.

This argument and the approach on which it is based is substantially different from neoclassical or new institutional economics (mainstream economics in this paper) typically based on general equilibrium analysis and Kuznets’ ideas of inequality (see an extensive review by Asongu, 2016). For mainstream economists, inequality is not necessarily considered to be bad because it can be an incentive to hard work. Second, inequality is the result of individual effort or sloth such that the difference between the incomes and wealth can be attributed to hard work or laziness. Otherwise, in general, inequality tends towards disappearance in the form of a spatial equilibrium. The neoclassical approach to the study of wealth and income concentrates largely on the economic aspects of wealth, not its social aspects.

When land is studied, the primary assumptions are that private property motivate its owners to work hard, invest, and trade in land which in turn, will improve the social conditions of landowners and support national economic growth. However, this approach suffers conceptual bias because for most land in the Global South (e.g., Africa and the Pacific), neither of these assumptions is valid. Instead, land and property are communally held, managed, and used such that even when individual kith and kin pursue personal aspirations with ‘their land’, the use must be governed by and in pursuit of the collective good broadly defined (Anderson, 2011; Elahi & Stilwell, 2013). So, there is no congruence between neoclassical assumptions and the real land economy of customary landowners. New institutional economics (NIE), on the other hand, accepts that neoclassical economics is in error in making methodological individualist assumptions about customary land tenure, however, NIE assumes that such customary systems will ipso facto evolve to Western land tenure systems (see, for example, Yoo & Harris, 2016; The Economist, 2019) – without acknowledging counter ‘hegemonic’ forces that resist such evolution and the autonomous development of customary land tenure (Moyo & Yeros, 2005). The argument in this paper, drawing on Ely’s approach, runs against both neoclassical and new institutional economics for these reasons.

The argument in this paper is also quite distinct from Marxian analysis and claims. For Marxists, inequality is reprehensible, and under the capitalist mode of production, is persistent, and expansionary. The source of inequality, for Marxists, is the capitalistic exploitation of labour. A rich body of Marx’s work on land has recently been analysed (Munro, 2022), but in general Marxist political economy, land is of secondary importance. So, Marxists tend to seek changes in the distribution of surplus-value and the economic structure. Ely’s approach is much wider. Focused on institutions that support the economic structure, land is of particular interest. In this sense, Ely’s pursuit of just distribution is akin to that of Henry George, but his approach differs from that of George in many respects (for a review of the work of Henry George, see Gaffney, 2009; 2015). For instance, in terms of the weight Ely gives to other institutions and their relationship with property rights, in terms of how inequalities need to be addressed, and in terms of whether all rent is to be regarded as surplus. Nevertheless, Ely’s institutionalism complements other heterodox approaches rather than demolishing them. Therefore, Ely’s surplus approach to rent is one more scaffold not only to build a heterodox alternative but also to more deeply mark the terrain and intellectual apparatus of original institutional economics and political economy in general.

Critiques and Contradictions

Ely has been widely criticised. Concerns have ranged from his apparent support of propertied interests to his non-commitment to the founding ideals of the United States. Some have pointed to “his handling of legal material” as being of “a slip-shod character” (Cohen, 1917, p. 399). Others point to his overly optimistic view about the neutrality of judges (e.g., Hand, 1915). Ely himself suggested many ways to overcome such challenges, either by using existing legislation or creating new legislation. As noted by Swayze (1915, p. 825): “the right of taxation, the right of eminent domain, the right to exercise the police power, the right to control transfers, especially by way of inheritance, the right to exempt certain property from education and distress in order that a man [sic] may not be deprived of the means of doing his part in the world by working at his trade or calling”. Ely also suggested a flexible system in which new judges are appointed to overturn archaic judicial philosophies and practices (Swayze, 1915, p. 828), but these positions have been criticised. For example, “It is far better to wait until public opinion is finally settled on a disputed question, and time makes it possible to determine whether proposed changes are real reforms or not” (Swayze, 1915, p. 828). With respect to his surplus approach to rent, these criticisms need to be extended in at least two respects centred mainly on questioning his theorising of inequalities and his trust in “police power”. The surplus approach to rent locates inequalities primarily at the national level where race, gender, class, nor other identities are considered seriously. Yet, as a large body of research has shown, the rise in inequalities is not only at the national level, but can also be seen at the subnational, regional, and global levels (e.g., Bush & Szeftel, 2000; Cahill & Stilwell, 2008; Gaffney, 2009, 2015; Plack, 2009; Obeng-Odoom, 2021). Whatever the scale, inequalities have taken particular identity lines, ranging from caste, colour and class, to gender, disability, and sexuality, among others.

These inequalities and social stratification arise from different underlying institutions and historical periods, and they have entirely different geographical forms. However, they have all tended to lead to similar outcomes: Dispossession, Discrimination, and Concentration. In the United States, this privatization of land has had a distinctive racial orientation. As we see in N.D.B Connolly’s (2014) book: A World More Concrete: Real estate and the remaking of Jim Crow, the process of instituting private property was also the process of establishing white supremacy. Not only have Zoning laws, the use of state power of eminent domain, and so-called campaigns to improve housing for African-Americans in ghettoes ended up dispossessing and displacing African Americans of their land but also these forces of stratification have locked them into the rental market as renters or subprime mortgagors and associated them with undesirable features (e.g., crime, grime, drugs, and dereliction) that drive down property values, while white Americans have made millions off them in rent and mortgage payments.

While there have been black property owners, and these have collaborated with white property owners, for example, by lending each other money to pursue propertied empires, the institutions in that country have made it increasingly difficult for them to expand their property holdings for example by making it much more difficult to obtain the types of loan that white property owners can access to surge ahead (Connolly, 2014, p. 1-16). Such Jim Crow barriers matter, but as Darity and Mullen (2020) have shown recently, these processes of racialised wealth inequalities extended from the era of slavery through Jim Crow to modern multiples of discrimination and privilege. In Africa, the number of sticks in the bundle of private property rights has significantly increased. Common water is now being fenced off and being parcelled out as part of the sphere of private property, as we see in the recent book by John Anthony Allan and his colleagues: Handbook of Land and Water Grabs in Africa (2013). In Ely’s terminology, then, both the extensivity and intensivity of private property have been substantially widened, but they have concentrated wealth in private and racially privileged hands.

None of these engaged Ely’s attention in his time. It is not that Ely was unaware of persistent stratification. He was, but he thought it was deserved, often canvasing a particular type of eugenics in which so-called inferior races would be oppressed to such a level that they would be exterminated: “we have got far enough to recognize that there are certain human beings who are absolutely unfit and should be prevented from a continuation of their kind” (Ely cited Leonard, 2016, p. 74). “Negroes”, Ely noted, “are for the most part grownup children, and should be treated as such” (cited in Leonard, 2016, p. 121). Ely campaigned to exclude immigrants from opportunities because he considered them to be racially inferior (Leonard, 2016, p. 8). He campaigned against giving work to the disabled, to pave way for the worthy poor (Leonard, 2016, p. 131-132), while he deemed white people to be of the “superior classes” (cited in Leonard, 2016, p. 52).

Ely, in short, echoed the dark illiberal side of progressive institutional economists who also sought protection for women, but not equality with them (Leonard, 2016, p. 182-185). Ely, for example, deemed women to be biologically weaker and hence in need of protection (Leonard, 2016, p. 170 & 174). Accordingly, Ely’s surplus approach overlooks, even reinforces, the colour of rent, and the multiple identities of those marginalised by the extraction of rent across the uneven landscape of global political economy both in terms of analysis and proposed ways of addressing the problem.

Yet, in these processes, it is the majority poor peasants, migrants, politically marginalised, blacks, women, nomads and others of minority identities who give up or are made to give up their land and from whom community water is taken. Research published in Feminist Economics establishes that women’s land is often the first and easiest targets. Established plantations disrupt long-standing gendered roles that guarantee certain jobs for women by employing men, often from different communities, to take up women’s jobs (e.g., Daley and Pallas 2014; Poro and Neto, 2014). Mining and drilling activities surged at the height of land grabs Cooney, 2016; Barkin, 2017; Cooney & Freslon, 2019).

41Often the ‘winners’ do not control land forever, but the process can range from 50 to 99 years. People are hardly consulted, as powerful groups take unilateral decisions or government officials even in clear contravention of the law are over-excited about the social benefits the project will bring and, hence, the social theory of this private property movement is that enclosures are good for society. Jobs, technology, knowledge transfer, foreign exchange, and modernisation, development and positive social change have all been promised as a justification for these enclosures – albeit they have remained just that: promises (Obeng-Odoom, 2013a; Elhadary & Obeng-Odoom, 2012; Obeng-Odoom, 2020a). In effect, these multiple transformations have transferred rent from the Global South to the Global North, from blacks to whites, from men to women, from weaker classes, castes, and colours to more powerful groups.

The outcomes have been changing property relations in favour of the rich, wealthy, and mighty. That is, Polanyi’s (1945) “great transformation” has generated stratified hierarchical property relations characterised nearly always with the weaker groups taking the lower and more precarious position in the property ladder. In the case of real estate, indebted mortgage recipients live with the myth that they are property owners when in fact, they only possess property and hold conditional rights that can easily be terminated by the real property owners: banks, doubling as speculators, and landlords who double as bankers, supported by a wide range of professional valuers and real estate organisations (Obeng-Odoom, 2020b). In the case of agrarian relations, proletariats become converted into wage labour sometimes for 50 years, others for much longer. So, while the land will ultimately return to the land-owning communities, community members will have long passed on – especially in countries where the life expectancy is less than 70 or they become much more wretched than they were prior to the process.

By country, the top 10 appropriators as of 2012 were the USA, Malaysia, the UK, China, the United Arab Emirates, South Korea, India, Australia, and South Africa (Land Portal, 2012), while countries in Sub-Saharan Africa provide 70 percent of all land captured (World Bank, 2010). Leon’s (2015) more recent work suggests that these figures are accurate: most of the land purchased has been located in Africa and most of the centres from which the purchases have been financed are the world’s super-rich or rich cities, most notably New York, London, Singapore, Seoul, and Kuala Lumpur (Leon, 2015). Seventy-five percent of the time, the land acquired in such processes is put to the cultivation of biofuel plants, being a change of their previous use (food/non-food uses).

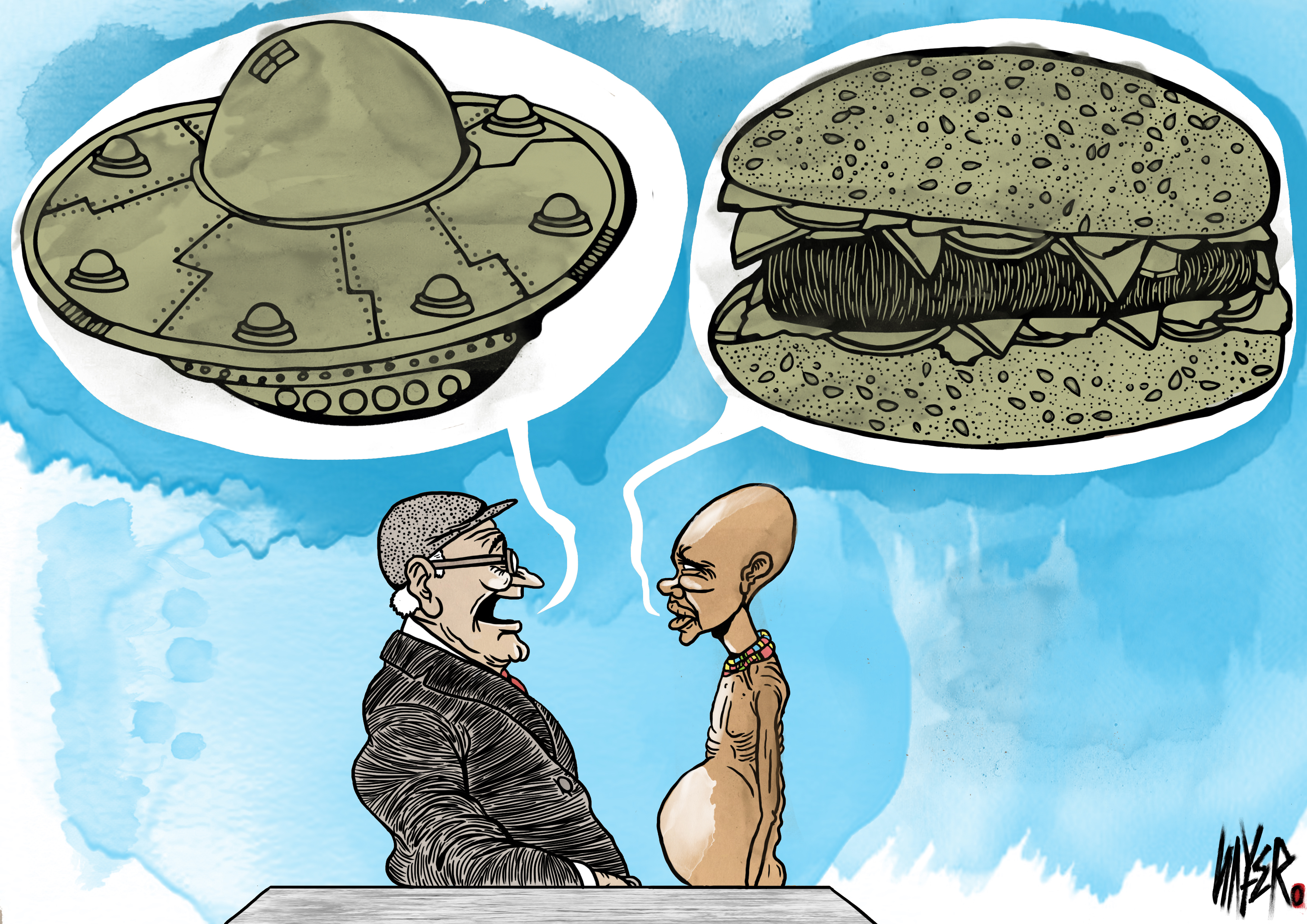

The rest is put to food cultivation, but mainly for export purposes (Borras & Franco, 2012; International Land Coalition, 2012). In turn, access to local food consumption has become insecure or expensive for those in weaker property relations. So, the increase in global food security is mainly for the so-called ‘developed regions’ for which both the number and percentage of people who are undernourished are on the decline. As shown in Table 1, such regions have consistently recorded a decline in undernourishment problems – “A state, lasting for at least one year, of inability to acquire enough food, defined as a level of food intake insufficient to meet dietary energy requirements” (FAO, IFAD & WFP, 2014, p. 50)

Africa (Sub-Sahara and North Africa), where most parcels of land have been taken up in the ongoing global process of private enclosure, is the region with the worst trends in feeding its people. While the causes of undernourishment are many and certainly not simply restricted to the loss of land, the trend in Africa is not a mere question of ‘correlation’. Rather, the reduction of land available for food production is a major contributor to the maldistribution of the burden of food insecurity which in turn, feeds into the problem of undernourishment. As noted in the Africa Agriculture Status Report, “large acquisitions by nationals and foreigners in other countries have greatly increased inequality. From the seller’s point of view, there is concern about distress sales where poor households have no alternative for meeting emergencies than to sell their land at very low prices” (AGRA, 2013, p. 36). Land taken is typically used for agribusiness. As Timothy Wise has shown in his latest book, Eating Tomorrow (Wise, 2019), such a regime of agriculture undermines ecologically sustainable agriculture with its emphasis on genetically modified seeds, excessive emphasis on the use of agro-based fertilizer and other chemicals, and the insistence on viewing agriculture as a for-profit business.

Wise’s work is revealing. Most farmers he has interviewed in Africa are opposed to agribusiness. He refers to his interviews with female farmers in Mozambique who reject agribusiness because, for the farmers, such food system only serves the interest of the West and the local landlord class (Wise, 2019, chap. 1). “Seeds of opposition”, to quote The Economist (2019, p. 32-33), were sown in Mozambique eventually. Prosavana, a corporate initiative, aimed at turning 107,000 square kilometres (a large tract of land analogous to the size of Bulgaria) into a food basket, was launched in 2009. By 2019, not much progress had been made. Rather, plans had been afoot to raise $2bn private equity funds for another agri-business in 2013. By 2019, such was the opposition that The Economist (2019, p. 32-33) described the situation as “stony ground”. Stefan Ouma (2020) has offered a more systematic, more up-to-date account. The financialisation of land and resulting dispossession and deprivation have become even more serious today. The question, then, is no longer whether such inequalities exist but what institutional forces or in the terminology of régulationists, “institutional forms” (Vercueil, 2016), drive, sustain, and mould the trends in the distribution of wealth in relation to property.

Whether the ‘police power’ intended to ensure that such privatisation and private capture of value is an effective check requires careful analysis. In his tome, Legal Foundations of Capitalism, J.-R. Commons, Ely’s student, carefully documents the changing meanings of ‘police power’ in the American and the English courts (Commons, 1924). The courts will often take a larger view of ‘value’ and the ‘economy’ than neoclassical economists would because the courts consider the economy as constituted by the interaction or transaction between two people (plaintiff and defendant), constituting electrons in motion (see Commons, 1924, p. 7-8): not individuals, atomistic individuals, whose actions are static as in neoclassical economics.

Yet, even the courts cannot ipso facto confirm what is ‘reasonable value’ and how the police power might be used, as the use depends on the particular location, time, and constitutional provisions (Commons, 1924). Nowhere is this contingent interpretation better demonstrated than in India where judicial decisions on the question of public and private space have been shifting dramatically from pro-marginalised groups interests to business interests. The state and its agencies even in the days of pro-hawker judicial decisions had always found ways around court decisions to pursue their own interest (Schindler, 2014). Elsewhere, in many cases, courts have used the police power to favour the rich. In one case, this police power was exercised in favour of investors who had been misled into investing in a private land venture in Togo, West Africa (Obeng-Odoom, 2016). Lyn Ossome has conducted a detailed analysis of police power, which seeks to answer the question: “Can the Law Secure Women’s Rights to Land in Africa?”

After considering the evidence, she notes:

There is still no conclusive evidence of the viability of customary law’s efficacy in securing women’s rights to land. Rather, contemporary land deals take place in the context of a legal, political, and economic terrain that requires constant negotiation and reinterpretation in line with the lived realities of communities and women within them. This study demonstrates that customary law is not yet exhausted as an avenue for redress. It exposes the colonial fallacies upon which the customary was based, the attempts to put it aside, and the assumptions that underlay these attempts. It also examines the problematic nature of formalisation in the contexts of land acquisitions, which in essence pits the state against itself. (Ossome, 2014, p. 172)

While this evidence relates to customary law, the research findings about constitutional law and courts follow similar patterns. John Mbaku’s (2018) research on constitutional protection of minority rights in Africa makes the point. According to him, constitutional structure and constitutional making are contingent on socio-historical context. Forcibly united under colonialism, countries such as Cameroon have tried to build constitutions, but such documents are exclusive not only in their rules, but also in their application and enforcement. The Supreme Court of Ghana might be much more inclusive both in how the Ghanaian constitution was drafted and is interpreted (Date-Bah, 2015). But both the US Supreme Court and the South African Supreme Court have been exclusive and ideologically biased against minorities. Typically, the rules of court, constitutional provisions, the complicity of judges and lawyers, and the wider political economies of the two countries combine to concentrate land in the hands of white, wealthy and powerful landlord classes (Bonica & Sen, 2020; Ngcukaitobi, 2021).

Fundamentally, whether inclusive or exclusive, long-term inequalities, social stratification, and property concentration have increased in Africa (Obeng-Odoom, 2021) and elsewhere in the world (Stilwell, 2019; Piketty, 2014, 2020; Darity & Mullen, 2020). Indeed, in the US, research (Maclean, 2017) shows that James Buchanan, the leading theorist behind the public choice school of economics, conceived of the Supreme Court as an institution to support white propertied interests, rather than as an instrument of harmonious arbitration between the landlords and ordinary members of the American society. Not only are black judges in the minority, research shows that their decisions are more likely to be overturned on appeal (e.g., Sen, 2015).

That said, this contingency does not amount to a concerted attempt by lawyers and judges to create what Marxists perceive to be a deliberate institutional framework to encourage extractivism for foreign interests (see, for example, Freslon & Cooney, 2019, p. 26-27). Nigerian courts, for instance, have tried to constrain extractivisms of various kinds when seeking to bring transnational oil companies under their jurisdiction (Obeng-Odoom, 2020a, p. 195-196).

International law itself has been complicit in creating concepts such as terra nullius which have been used to justify extractivisms and many imperial courts like those in Britain still make decisions on many occasions to favour the transnational corporations from the imperium. (For a discussion of concepts and international law, see Amin, 2020). While the Prosecutor at the International Criminal Court (ICC) has promised to prosecute land grabbers at the ICC, no such action has taken place (Surma, 2021). If it does, there is no guarantee of success. It follows that the police power is no guarantee, as suggested by Ely’s surplus approach to rent.

Conclusion: Rent and Reconstruction

Rent is central to political-economic discussion of long-term inequality and social stratification. However, rent is largely neglected in neoclassical-economic analysis of inequality. The surplus approach to rent tries to rectify this problem. The social theory of property, advanced by Ely, offers a distinctive contribution to the surplus approach to rent. Not only does it differ from other surplus approaches in terms of its analysis of how rents arise, Ely’s surplus approach is also distinctive in emphasising land as a ‘bundle of rights’ and reform, not via the socialisation of rent for wider social policy or for workers’ liberation, but through revisiting and revamping the courts (see, for example, Ely, 1940, p. 76, 80-81).

Yet, as the evidence in this paper has shown, the social trust bestowed on private property owners has long been broken and the police power offered as a check on the excesses of private property ownership is way too limited to serve as an effective constraint on the propertied class. The concentration of land-wealth has dramatically normalised, and pre-transformation property relations have been moulded in diverse, different and differentiated ways across scales and over time, particularly in the extractivist forms of accumulation.

Not all these are surprising. Ely’s surplus approach is more strongly focused on national, not multi-scalar global inequalities and global social stratification. Inherent in the social theory of property rights is structural bias against racial and other minorities. As discussed in this paper, the surplus approach also places too much categorical weight on the police power which, in practice, is clearly contingent. Marxian revolutionary alternatives are similarly uncertain. Other evolutionary surplus approach alternatives – including Georgist political economy – are a bit more certain. Drawing on multi-level state power, community, and global institutions, a Georgist alternative can more reliably socialise rent as surplus.

The trouble with all the surplus approaches is that they are either race blind or racist. At the same time, it could be analytically useful to bring Ely ‘back in’ to the debate about the social theory of property and distribution of wealth in extractivist and rentier societies, and link inequalities to institutions, notably the courts. In this way, Ely is one antidote to Buchanan in the sense that he sees institutions as one set of ways to transform society in an evolutionary inclusive way. But, like Buchanan, Ely’s theorizing also explicitly sought to subjugate minorities, especially black people.

If Ely’s theorizing can succeed in this role, therefore, then his theory has to be emptied of its problematic underpinnings which can helpfully be replaced by stratification economics, pioneered by black political economists to become the most advanced school of institutional and evolutionary political economy on inter-group inequalities, analysis of which is a story for another time (for further reading, see Darity, 2009; Darity et al., 2015; Darity, 2021). What can be stressed even now, is that the surplus approach to rent can benefit from the broad approach offered by the régulation school. This group of thought seeks an historical approach that links previous socio-economic and ecological processes to present ones (e.g., rentier processes to new extractivist processes). This school of thought also provides the canvass for an open-ended approach to uniting or amalgamating diverse forms of institutional and evolutionary alternatives. The aim is usually to question orthodoxy, more deeply understand, and more comprehensively change uneven and unequal global political economy. Clearly, one way for stratification to advance is for it to take the driving seat in the surplus approach to rent.

References

AGRA (2013), Africa Agriculture Status Report, Nairobi, AGRA.

Alexander G. S. & E. M. Peñalver (2012), An Introduction to Property Theory, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, coll. « Cambridge introductions to philosophy and law ».

Allan J. A., Keulertz M, Sojamo S & W. Jeroen (eds.) (2013), Handbook of Land and Water Grabs in Africa, Abingdon (UK) & New York (NY), Routledge, coll. « Routledge international handbooks ».

Amin G. F. (2020), Encountering Underdevelopment: International law, capital accumulation and the integration of Sub-Saharan Africa into the world system (1492-1900), Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Law, University of Helsinki, Finland.

Anderson T. (2011), « Melanesian land: The impact of markets and modernisation », Journal of Australian Political Economy, no 68, p. 86-107.

Asongu S. A. (2016), « Reinventing foreign aid for inclusive and sustainable development: Kuznets, Piketty and the great policy reversal», Journal of Economic Surveys, vol. 30, no 4, p. 736-755.

Bonica A & M. Sen (2020), The Judicial Tug of War: How Lawyers, politicians, and political incentives shape the American judiciary, New York & Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Borras S. M Jr. & J. C. Franco (2012), « Global land grabbing and trajectories of agrarian change: A preliminary analysis», Journal of Agrarian Change, vol. 12, no 1, p. 34-59.

Bradizza L (2013), Richard T. Ely’s Critique of Capitalism, New York, Palgrave MacMillan.

Broome A. (2015), « Back to Basics: The Great Recession and the narrowing of IMF policy advice», Governance, Special issue, vol. 28, no 2, p. 147-165.

Bush R. & M. Szeftel (2000), « Commentary: The Struggle for Land», Review of African Political Economy, vol. 27, no 84, p. 173-180.

Cohen M. R. (1917), « Property and Contract in Their Relation to the Distribution of Wealth. By Richard T. Ely », International Journal of Ethics, vol. 27, no 3, p. 388-389.

Commons J. R. (1924), Legal Foundations of Capitalism, New York, The Macmillan Company.

Connolly N. D. B. (2014), A World More Concrete: Real estate and the remaking of Jim Crow South Florida, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, coll. « Historical studies of Chicago Press ».

Agostina C. (2016), « The dark side of the boom: land grabbing in dependent countries in the twenty-first century », International Critical Thought, vol. 6, no 1, p. 79-100.

Barkin D. (2016), « Violence, inequality and development », Journal of Australian Political Economy, vol. 78, p. 115-131.

Boyer R. (2015), Économie politique des capitalismes. Théorie de la régulation et des crises, Paris, La Découverte, coll. « Grands Repères ».

Butler G. (2002), « Beyond eclecticism: A surplus-orientated approach to political economy », Journal of Australian Political Economy, no 50, p. 89-97.

Cahill D. & F. Stilwell (2008), « Editorial Introduction: The Australian economic boom: 1992 – ?”, Journal of Australian Political Economy, no 61, p. 5-11.

Cooney P. (2016), « Reprimarization: Implications for the environment and development in Latin America: The cases of Argentina and Brazil», Review of Radical Political Economics, vol. 48, no 4, p. 553-561.

Cooney P. & W. S. Freslon (2019), « Introduction: Environmental impacts of transnational corporations in the Global South», Research in Political Economy, vol. 33, p. 1-8.

Cotula L. (2013), « The new enclosures? Polanyi, international investment law and the global land rush », Third World Quarterly, vol. 34, no 9, p. 1605-1629.

Daley E. & S. Pallas (2014), « Women and land deals in Africa and Asia: Weighing the implications and changing the game », Feminist Economics, vol. 20, no 1, p. 178-201.

Darity W. Jr. (2009), « Stratification economics: Context versus culture and the reparations controversy », Kansas Law Review, vol. 57, p. 795-811.

Darity W. A. Jr. & K. Mullen (2020), From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the twenty-first century, Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press.

Darity W. A. Jr., Hamilton D. & J. Stewart (2015), « A tour de force in understanding intergroup inequality: An introduction to stratification economics », The Review of Black Political Economy, vol. 42, nos 1-2, p. 1-6.

Date-Bah S. (2015), Reflections on the Supreme Court of Ghana, London, Wildy Simmonds and Hill Publishing.

Elahi K. Q. & F. Stilwell (2013), « Customary land tenure, neoclassical economics and conceptual bias », Niugini Agrisaiens, vol. 5, p. 28-39.

Elhadary Y. A. E & F. Obeng-Odoom (2012), « Conventions, changes and contradictions in land governance in Africa: The story of land grabbing in Sudan and Ghana », Africa Today, vol. 59, no 2, p. 59-78.

Ely R. T. (1914), Property and Contract in Their Relations to the Distribution of Wealth, London, Macmillan and Co., Limited.

Ely R. T. (1922), Outlines of Land Economics, vol. 2, Ann Arbor, Michigan Edwards Brothers Publishers.

Ely R. T. (1928), « Land Income », Political Science Quarterly, vol. 43, no 3, p. 408-427.

Ely R. T. (1938), Ground Under Our Feet, London, New York & Toronto, Macmillan and Co., Limited.

Ely R. T. (1940), Land Economics, New York, The Macmillan Company.

Ely R. T., Hess R. H, Leith C. K. & T. N. Carver (1917), The Foundations of National Prosperity, New York, The Macmillan Company.

FAO, IFAD & WFP (2014), The State of Food Insecurity in the World, Rome? FAO.

Faudot A (2019), « Saudi Arabi and the rentier regime trap: A critical assessment of the plan Vision 2030», Resources Policy, vol. 62, p. 94-101.

Fine B (2019), « Marx’s rent theory revisited? Landed property, nature and value », Economy and Society, vol. 48, no 3, p. 450-461.

Freslon W.S. & P Cooney (2019), « Transnational Mining and Accumulation by dispossession », Research in Political Economy, vol. 33, p. 11-34.

Gaffney M. (2009), After the Crash: Designing a depression-free economy, Malden (MA), John Wiley and Sons Ltd, coll. « Studies in economic reform and social justice ».

Gaffney M. (2015), « A real-assets model of economic crises: will China crash in 2015? », American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 74, no 2, p. 325-360.

Griethuysen P. van (2012), « Bona diagnosis, bona curatio: How property economics clarifies the degrowth debate », Ecological Economics, vol. 84, p. 262-269.

Haila A. (1990), « The theory of land rent at the crossroads », Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 8, p. 275-296.

Haila A. (2016), Urban Land Rent: Singapore as a property state, Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell.

Hand L. (1915), « Review of Property in Their Relations to the Distribution of Wealth by Richard T. Ely », Harvard Law Review, vol. 29, no 1, p. 110-112.