Archive

Income Inequality and Citizenship: Quantifying the Link

Our level of income is unarguably dependent on where we live in the world. But evidencing this is tricky. This Posting presents a model that explains global income variability using one variable only – where you live. The results suggest that we might want to reassess how we think about both economic migration and global inequality of opportunity.

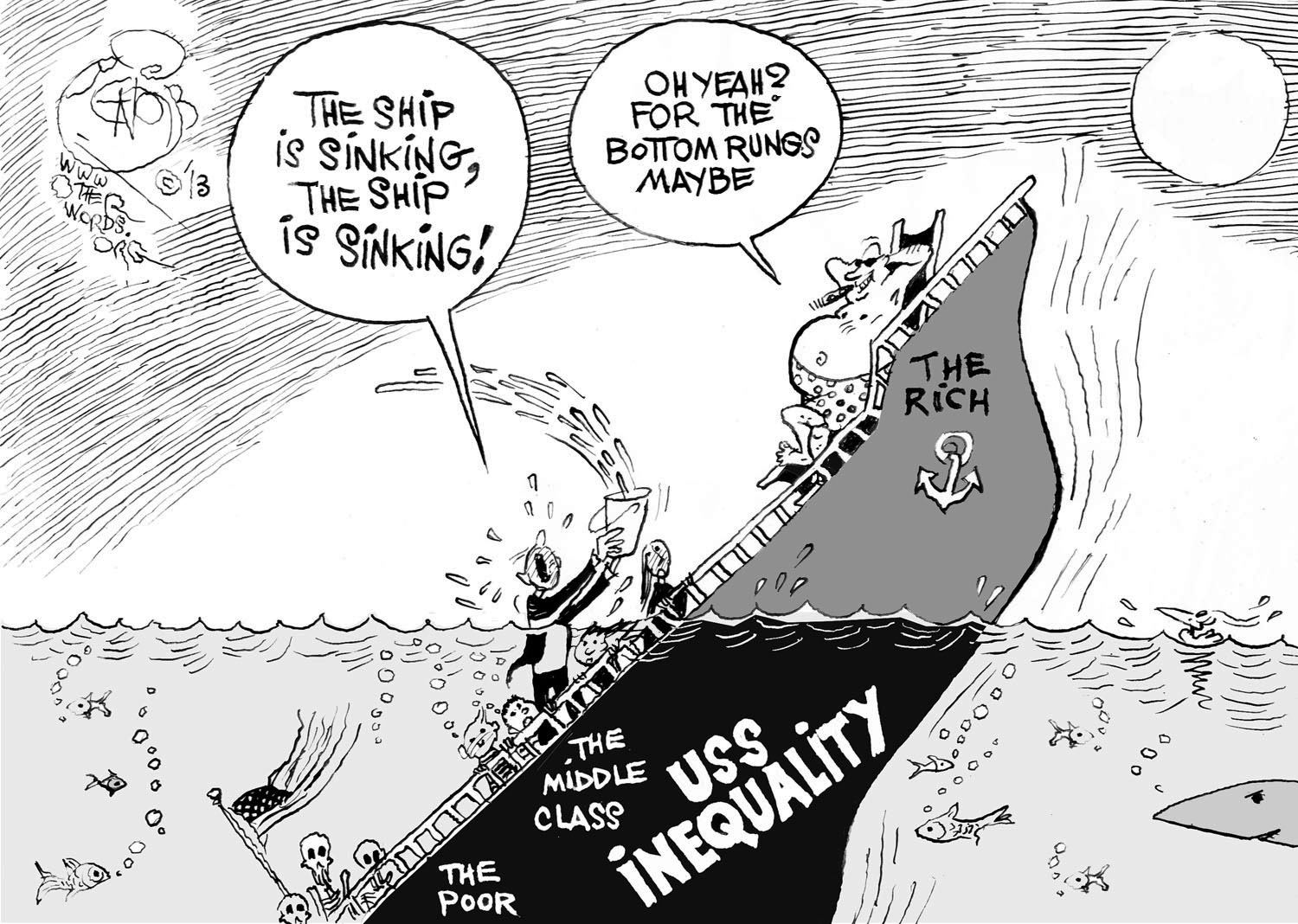

It is as obvious as it is well known that the world is unequal in terms of individuals’ incomes (e.g. Mohammed 2015). But it is unequal in a very particular way – when split into ‘inequality within countries’ and ‘inequality between countries’, the latter accounts for by far the biggest gap.

Inequality within countries measures, for instance, gaps between poor and rich Americans or between poor and rich Chinese. For simplicity, let’s call it ‘class’ inequality. But there is also another equally obvious inequality – that between rich and poor nations. More specifically, this inequality is measured as the gap between the ‘representative’ or ‘average’ individuals of any two countries, be they Morocco and Spain or Mexico and the US. For simplicity, let’s call this ‘locational’ inequality.

Inequality, as it is commonly understood in today’s world, is such that whatever measure we choose, the lion’s share of global inequality is ‘explained’ by the differences in mean incomes between countries.

This was not always the case. Although our data for the past are far more tentative than our data for today’s global income distribution, we can still state with little doubt that the dominant type of equality in the 19th century was that within countries (see Milanovic 2011).

Citizenship Premiums and Penalties

If income differences between countries are large then your income will significantly depend on where you live, or even on where you were born (97% of the world’s population remain in the countries where they were born). This is what I call a ‘citizenship premium’ (or a ‘citizenship penalty’) – a ‘rent’ that a person receives if he or she happens to be born in a rich country, or, if we use the terminology introduced by John Roemer, an ‘exogenous circumstance’ which is independent from any one individual’s effort and episodic luck (Roemer 2000).

How big is citizenship rent, how does it vary with one’s position in the income distribution, and what does it imply for global inequality of opportunity and migration?

Estimating Citizenship Rent

I estimate citizenship rent by using data collected from household surveys conducted in 118 countries in and around the year 2008 (Milanovic 2015). For each country, I have micro-level (household) data ordered into 100 percentiles, with individuals ranked by their household per capita income. This gives 11,800 country/percentiles with ‘representative’ per capita incomes expressed in dollars of equal purchasing parity, making incomes across countries comparable.

I ‘explain’ these incomes using only one variable – the country where individuals live. Of course, people living in the US will tend to have higher incomes at any given percentile of the distribution than people living in poor countries in, for instance, Africa. But how will it look for the world as a whole? In a least-square dummy variable regression, I use Congo (the poorest county in the world) as the ‘omitted country’ so that I can express the citizenship premium in every other country in terms of the income gain compared to Congo. The premium for the US is 355%, it is 329% for Sweden and 164% for Brazil. But for Yemen, another very poor country, it’s 32%.

According to this regression, we can explain more than two-thirds of the variability in incomes across country/percentiles by only one variable – the country where people live. This estimation shows that, as we thought, a lot of our income depends on where we live.

Citizenship Rent across the Distribution

But this is only an average premium that compares countries. Does citizenship rent vary along the entire income distribution? If I were to take into consideration only people belonging to the lowest part of the income distribution in each country, would the premium still be the same?

Intuition may help here. Suppose that I focus only on the incomes of the lowest decile (with rich countries more equal than poor countries). Then the gap between rich and poor countries should be greater for the very poor people than for the average individual. And this is indeed what we find – Sweden’s citizenship premium compared to Congo is now 367% versus 329% on average. But Brazil’s is 133% versus 164%. The situation at the top is exactly the opposite – Sweden’s advantaged position at the 90th percentile of the income distribution is ‘only’ 286%, but Brazil’s becomes 188%.

Implications for Migration

The existence of the citizenship premium has obvious implications for migration: people from poor countries will have the opportunity to double or triple their real incomes by moving to a rich country.

But the fact that the premium varies as a function of one’s position in the income distribution carries additional implications. If I consider moving to one of two countries that have the same average income, my decision on where to migrate – based on economic criteria alone – will also be influenced by my expectations regarding where I may end up in the recipient county’s income distribution. My decision will thus be influenced by the extent to which the recipient country’s income distribution is unequal.

Suppose that Sweden and the US have the same mean income. If I expect to end up in the bottom part of a recipient country’s distribution, then I should migrate to Sweden. The poor people in Sweden are better off compared to the mean, and the citizenship premium, evaluated at lower parts of distribution, is greater. The opposite conclusion follows if I expect to end up in the upper part of the recipient country’s distribution – I should migrate to the US.

This last result has unpleasant implications for rich countries with greater ‘in-country’ equality. More equal rich countries will tend to attract lower-skilled migrants who generally expect to be placed in the bottom part of the recipient country’s distribution. Developing a national welfare state would have the perverse effect of attracting migrants who can contribute less.

Even in this rough sketch, we also have to consider the levels of social mobility in recipient countries because more unequal countries with strong social mobility will, everything else being the same, tend to appeal to more skilled migrants.

Global Inequality of Opportunity

The mere existence of a large citizenship premium implies that there is no such a thing as global equality of opportunity because a lot of our income depends on the accident of birth.

So should we strive for global equality of opportunity or not? It is a political philosophy question that philosophers have thought much more about than economists. Some, following John Rawls in The Law of Peoples, believe that this is not an issue and that every argument for global equality of opportunity would conflict with the right of national self-determination. But other political philosophers like Thomas Pogge believe that in an interdependent world, the dominant role of chance in people’s life is not to be accepted lightly (Pogge 2008). I am not proposing a solution to this issue, yet, I believe that economists should not shy away from addressing it.1

As gaps between nations diminish, mostly thanks to the high growth rates of Asian countries, the citizenship rent will tend to reduce. But there is such a huge gap today that even a century of much higher growth in poor countries (in comparison to rich countries) will not eradicate citizenship rent.

However, it will reduce. As it does, it will also reduce overall global inequality. This might then lead us to a world not dissimilar to the mid-19th century, in which class is again more important for one’s global income position than location.

Do I hear the distant sound of Marx?

References

Milanovic, B (2011), The haves and the have-nots: a short and idiosyncratic history of global inequality, New York: Basic Books.

Milanovic, B (2015), “Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of Our Income Is Determined By Where We Live?”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 97(2): 452-460.

Mohammed, A (2015), “Deepening income inequality”, World Economic Forum report.

Pogge, T (2008), World Poverty and Human Rights, Polity Press.

Rawls, J (2001), The Law of Peoples, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J (2000), Equality of Opportunity, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shachar, A (2009), The Birthright Lottery, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Footnote

1 Legal scientists such as Ayalet Shachar have written about addressing global inequality from a legal standpoint, proposing a much more flexible and open definition of citizenship (see Shachar 2009).

Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession

Since 1988, rapid growth in Asia has lifted billions out of poverty. Incomes at the very top of the world income distribution have also grown rapidly, whereas median incomes in rich countries have grown much more slowly. This posting asks whether these developments, while reducing global income inequality overall, might undermine democracy in rich countries.

The period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Great Recession saw probably the most profound reshuffle of individual incomes on the global scale since the Industrial Revolution. This was driven by high growth rates of populous and formerly poor or very poor countries like China, Indonesia, and India; and, on the other hand, by the stagnation or decline of incomes in sub-Saharan Africa and post-communist countries as well as among poorer segments of the population in rich countries.

Anand and Segal (2008) offer a detailed review of the work on global income inequality. In Lakner and Milanovic (2013), we address some of the limitations of these earlier studies and present new results from detailed work on household survey data from about 120 countries over the period 1988–2008. Each country’s distribution is divided into ten deciles (each decile consists of 10% of the national population) according to their per capita disposable income (or consumption). In order to make incomes comparable across countries and time, they are corrected both for domestic inflation and differences in price levels between countries. It is then possible to observe not only how the position of different countries changes over time – as we usually do – but also how the position of various deciles within each country changes. For example, Japan’s top decile remained at the 99th (2nd highest from the top) world percentile, but Japan’s median decile dropped from the 91st to the 88th global percentile. Or, to take another example, the top Chinese urban decile moved from being in the 68th global percentile in 1988 to being in the 83rd global percentile in 2008, thus leapfrogging in the process some 15% of the world population – equivalent to almost a billion people.

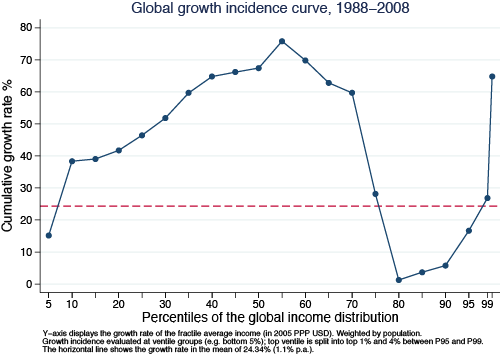

When we line up all individuals in the world, from the poorest to the richest (going from left to right on the horizontal axis in Figure 1), and display on the vertical axis the percentage increase in the real income of the equivalent group over the period 1988–2008, we generate a global growth incidence curve – the first of its kind ever, because such data at the global level were not available before. The curve has an unusual supine S shape, indicating that the largest gains were realised by the groups around the global median (50th percentile) and among the global top 1%. But after the global median, the gains rapidly decrease, becoming almost negligible around the 85th–90th global percentiles and then shooting up for the global top 1%. As a result, growth in the income of the top ventile (top 5%) accounted for 44% of the increase in global income between 1988 and 2008.

Fortunes of income deciles in different countries over time

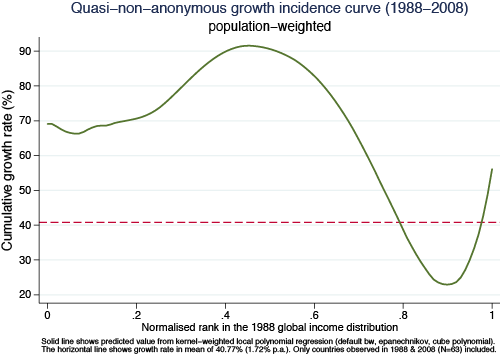

The curve in Figure 1 is drawn using a simple comparison of real income levels at given percentiles of the global income distribution in 1988 and 2008. It is ‘anonymous’ because it does not tell us what happened to the actual people who were at given global income percentiles in the initial year, 1988. In fact, the regional composition of the different global income groups changed radically over time because growth was uneven across regions. A ‘quasi non-anonymous’ growth incidence curve in Figure 2 adjusts for this – the growth rates are calculated for all individual country/deciles at the positions they held in the initial year (1988). The growth rate on the vertical axis (calculated from a non-parametric fit) thus shows how the country/deciles that were poor, middle-class, rich, etc. in 1988 performed over the next 20 years. The supine S shape still remains, although it is now slightly less dramatic.

People around the median almost doubled their real incomes. Not surprisingly, 9 out of 10 such ‘winners’ were from the ‘resurgent Asia’. For example, a person around the middle of the Chinese urban income distribution saw his or her 1988 real income multiplied by a factor of almost 3; someone in the middle of the Indonesian or Thai income distribution by a factor of 2, Indian by a factor of 1.4, etc.

It is perhaps less expected that people who gained the least were almost entirely from the ‘mature economies’ – OECD members that include also a number of former communist countries. But even when the latter are excluded, the overwhelming majority in that group of ‘losers’ are from the ‘old, conventional’ rich world. But not just anyone from the rich world. Rather, the ‘losers’ were predominantly the people who in their countries belong to the lower halves of national income distributions. Those around the median of the German income distribution have gained only 7% in real terms over 20 years; those in the US, 26%. Those in Japan lost out in real terms.

The particular supine S-shaped growth incidence curve (Figure 1) does not allow us to immediately tell whether global inequality might have gone up or down because the gains around the median (which tend to reduce inequality) may be offset by the gains of the global top 1% (which tend to increase inequality). On balance, however, it turns out that the first element dominates, and that global inequality – as measured by most conventional indicators – went down. The global Gini coefficient fell by almost 2 Gini points (from 72.2 to 70.5) during the past 20 years of globalisation. Was it then all for the better?

Probably yes, but not so simply. The striking association of large gains around the median of the global income distribution – received mostly by the Asian populations – and the stagnation of incomes among the poor or lower middle classes in rich countries, naturally opens the question of whether the two are associated. Does the growth of China and India take place on the back of the middle class in rich countries? There are many studies that, for particular types of workers, discuss the substitutability between rich countries’ low-skilled labour and Asian labour embodied in traded goods and services or outsourcing. Global income data do not allow us to establish or reject the causality. But they are quite suggestive that the two phenomena may be related.

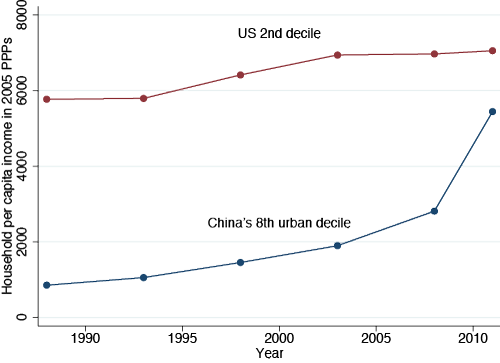

A dramatic way to see the change brought by globalisation is to compare the evolution over time of the 2nd US income decile with (say) the Chinese urban 8th decile (Figure 3). Indeed we are comparing relatively poor people in the US with relatively rich people in China, but given the income differences between the two countries, and that the two groups may be thought to be in some kind of global competition, the comparison makes sense. Here we extend the analysis to 2011, using more recent and preliminary data. While the real income of the US 2nd decile has increased by some 20% in a quarter century, the income of China’s 8th decile has been multiplied by a factor of 6.5. The absolute income gap, still significant five years ago, before the onset of the Great Recession, has narrowed substantially.

Political Implications

And even if the causality cannot be established because of many technical difficulties and an inability to define credible counterfactuals, the association between the two cannot pass unnoticed. What, then, are its implications? First, will the bottom incomes of the rich countries continue to stagnate as the rest of China, or later Indonesia, Nigeria, India, etc. follow the upward movement of Chinese workers through the ranks of the global income distribution? Does this imply that the developments that are indeed profoundly positive from the global point of view may prove to be destabilising for individual rich countries?

Second, if we take a simplistic, but effective, view that democracy is correlated with a large and vibrant middle class, its continued hollowing-out in the rich world would, combined with growth of incomes at the top, imply a movement away from democracy and towards forms of plutocracy. Could then the developing countries, with their rising middle classes, become more democratic and the US, with its shrinking middle class, less?

Third, and probably the most difficult: What would such movements, if they continue for a couple of decades, imply for global stability? The formation of a global middle class, or the already perceptible ‘homogenisation’ of the global top 1%, regardless of their nationality, may be both deemed good for world stability and interdependency, and socially bad for individual countries as the rich get ‘delinked’ from their fellow citizens.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, the movements that we witness do not only lead to an economic rebalancing of the East and West – in which both may end up with global output shares close to what they had before the Industrial Revolution – but to a contradiction between the current world order, where political power is concentrated at the level of the nation-state, and the economic forces of globalization which have gone far beyond it.

References

Anand, Sudhir and Paul Segal (2008), “What Do We Know about Global Income Inequality?”, Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1): 57–94.

Lakner, Christoph and Branko Milanovic (2013), “Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession”, World Bank Working Paper No. 6719, December.

The Post-Pandemic Brave New World

Policymakers’ choices during this disruption could shape their economies for decades to come

The pandemic struck a global economy that already was profoundly unsustainable—socially, environmentally, even intellectually.

Over the past four decades almost all advanced economies have become more polarized, with increasingly unequal income distributions. Developing economies lifted billions of people out of poverty, but in the process they, too, created their own rising inequalities and social tensions.

The global economy’s lopsided growth has brought us to the edge of catastrophic climate change.

And political upheavals in one country after another meant the world could not expect to go on as before. This pressure for change was reflected in economic policy thinking that was rapidly challenging old orthodoxies about public spending, central banking, and government intervention in the economy.

Then the coronavirus brought the most dramatic societal disruption and economic collapse in peacetime memory. Greater policy shifts took place in days or weeks than the most ambitious politicians could have dreamed of achieving in a lifetime. The enormity of the crisis made unintended radicals out of many political leaders as they intervened drastically in economic activity and took the risks of both workers and businesses onto the state’s shoulders on a massive scale.

We are now far enough past the initial onslaught to lift our gaze to the future, even if the pandemic’s course remains uncertain. It is time to consider how current policy choices will—and how they should—shape the long-term path for the world’s economies. This year’s transformation of both the economic and political landscapes—what economic risks and rewards we can realistically foresee and what is newly considered politically possible—means that things will never be the same. But how they will change is wide open, and policy choices made over the next few years will make a big difference to whether the post-COVID world favors broadly shared prosperity more than the status quo ante.

Sharpened societal contradictions

The fundamental economic fact about the pandemic is that it intensified existing societal fault lines. The preexisting policy debates about them have intensified too.

Concerns about rising inequality have been given new fuel because lockdowns entailed much greater hardship for people in jobs that could not be done from home. White-collar jobs, especially knowledge-intensive ones, already were increasingly well rewarded relative to manual jobs—in terms of pay, but also job security and predictability. Workers in most manual service jobs—hospitality and tourism, delivery, retail, and basic care—had long been getting a rougher deal, which worsened in the pandemic. Because they require physical proximity, these are the jobs most exposed to either lockdowns (when judged nonessential) or contagion (when essential). Women and the young are hit particularly hard because they are overrepresented in many of these sectors, as documented in the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook.

A second, related economic impact of the pandemic is an accentuation of the policy challenge from gig work and other irregular labor. It was already clear that in rich countries, nonconventional forms of employment and contracting were fitting ever less well with established welfare states. Informality continues to be an obstacle to developing safety nets in poorer countries (see Back to Basics in this issue of F&D). The lockdowns demonstrated the shortcomings of even well-developed state bureaucracies in reaching workers outside regular jobs. Politics and legislation often progressed at lightning speed to establish income-support programs, but the support sometimes failed to reach its target because governments could not identify the workers most in need.

Large, informal labor markets have long been a feature of poor economies. But the growth of a “precariat” of service workers—those with insecure employment and income and ill served by public services—is a principal reason why shockingly many people in the world’s richest countries have exceedingly thin financial buffers. Workers in sectors relying on low-paid and precarious work, hit disproportionately hard by the pandemic, were also less equipped to absorb such a shock to begin with.

Moreover, even unprecedented government steps to protect incomes have generally been insufficient to offset the disproportionate damage to those already worse off. As a result, the pandemic is likely not only to have reinforced chronic economic polarization, but to have intensified public awareness of it as a problem.

The economic fallout from the pandemic interacts with the underlying pressures of inequality in a third, less obvious, way. The sudden shift to remote working amounts to a steep change in business use of digital technology that is bound to affect production patterns and the distribution of economic surplus. While these effects may be hard to foresee, it is plausible that they could increase the productivity of those who already have the most “modern” jobs, intensive in cognitive skills and suitable for remote working. That could exacerbate the bifurcation of good and bad jobs.

The pandemic also played into political rifts over economic geography. Most obviously, it raised new questions over globalization—how interconnected countries can cope with contagion that spreads with travelers; with production disruptions from lockdowns in a global supply-chain manufacturing hub, as in Wuhan in January 2020; and with a sudden scramble for imported medical equipment.

Less obvious are the pandemic’s geographic effects within countries. Regional inequality has been one of the most toxic forms of economic polarization: starting about 1980, the post–World War II process of regional catch-up stagnated or even reversed as industrial jobs across national territories gave way to a concentration of knowledge services in their biggest cities. Now, while COVID-19 has spread in leading and declining cities alike, the economic disruption has temporarily changed how and where white-collar work is carried out—and could potentially be used by policymakers to alter permanently the geographic distribution of prosperity.

What is to be done?

For all these reasons, the pandemic is forcing policymakers to confront problems neglected for too long. But if things cannot go on as they were, the question remains, What policies should be implemented to change them and with what goals in mind? This is no easy question. The problems highlighted by the coronavirus crisis have defeated well-meaning attempts at improvement before.

But if things cannot go on as they were, the question remains, What policies should be implemented to change them and with what goals in mind?

But two things seem clear. The first is that the nature and quality of work are central, and any reform program must focus on creating higher-quality jobs for more people in more places. The second is that it must be big in scope and scale—something with ambition and motivational power comparable to the New Deal or the Marshall Plan.

Work must be central because it is where many of the chronic and pandemic-related economic challenges intersect: inequality, precarity, and the new informality; geographic disparity; and technological change. A much greater availability of high-quality jobs is also the main common yardstick to measure the success or otherwise of a comprehensive range of policies.

What these policies should be is, of course, the big question, and one that ought to be democratically anchored. In my recent book The Economics of Belonging, I argue for a program that

Embraces productivity growth and the technological upgrade of jobs by demanding more from employers . It is when unproductive jobs give way to more productive ones that work becomes safer, more pleasant, and better paid. In the European Nordic economies, wage egalitarianism has spurred productivity growth by making low-productivity labor uneconomical and incentivizing investment in productivity-enhancing capital. This approach can be adopted elsewhere to combat chronic low-paid, low-productivity work in lightly and rigidly regulated labor markets alike (both the United Kingdom and France have their precariats, for example) and to direct the reallocation about to take place as COVID-19 makes some activities unviable. Concretely, this means ambitious minimum wage increases and strong and strictly enforced workplace standards.

Produces a high-pressure economy with strong demand growth to give productive firms reason to expand and ensure new jobs appear as bad jobs disappear. High demand pressure is necessary to benefit those on the margins of the labor market—the young, ill-educated, and minorities—who tend to be fired first in a recession and hired last in an upturn. Concretely, this means running macroeconomic policy “hot,” calibrating monetary and fiscal policies to keep demand always slightly ahead of the economy’s capacity, to encourage companies to pull more people into the labor force and seek productivity-enhancing improvements. This is admittedly more easily done in large, rich economies, especially reserve currency issuers—which also puts the onus on their policymakers to lead global demand growth.

Lowers the cost of leaving a bad job and finding a better one . This requires a panoply of policies, including greater spending on skills, well-resourced active labor market policies, and social security reform to untie benefits from jobs. Changing jobs and upgrading skills are costly for workers, and are not undertaken if people have low buffers to live on between jobs. Direct and unconditional payments, including a basic income or negative income tax to avoid low-income traps in the benefit system, are ultimately the only way to overcome these obstacles. They are also the most effective and quickest way to improve living conditions for the worst off, especially when more targeted approaches are unable in practice to reach those most in need.

Reforms tax systems to encourage high-quality work. This means shifting taxes away from labor to encourage job-switching and hiring. The tax revenue loss must be made up elsewhere. This requires that a greater tax burden fall on capital, ideally through a net wealth tax, which is more productivity-friendly than other capital taxes. In addition, carbon taxes should be significantly increased to reallocate labor and capital in a green direction. The proceeds should be redistributed as a “carbon fee and dividend” or “carbon checks.” Finally, international corporate taxation must be fixed to level the competitive playing field between multinational and locally employing firms, and to allow governments more room for maneuver in taxing capital.

Reforms financial systems and tax rules to be less favorable to debt and more favorable to equity-type funding, which is both more conducive to productivity growth and restores an appropriate balance of risk between workers and investors. Governments should convert COVID-related rescue loans to companies that struggle to repay into tradable equity stakes.

Incentivizes a broader geographic spread of the highest-value-added jobs . The goal of policy should be to make more places host a critical mass of high-paying jobs. This is easier said than done, but at a minimum requires greater investment in transport and IT connectivity, local infrastructure, and amenities to make places attractive to live in, and policies to make financing available for new ventures in declining areas. The change to remote working provides a promising opportunity to use tax or regulatory incentives to shift good jobs from large central cities to more remote locations.

Reinterpreting the world

All of this may seem a tall order. The devil will be in the details: implementing large-scale reforms depends on solving myriad trade-offs and logistical difficulties at the micro level. But the challenge our economies face is so big that incremental policies are unlikely to achieve much—and are easy for vested interests to defeat. So any program with a hope of success must be of great scale and broad scope. Given that enormous policy changes have already happened, that no longer seems unrealistic.

The challenge our economies face is so big that incremental policies are unlikely to achieve much—and are easy for vested interests to defeat.

The old macroeconomic rules have been thrown out. Politicians who not long ago intoned about fiscal responsibility preside over record-breaking deficits, actively choosing to open the budgetary floodgates to sustain people’s incomes and companies’ liquidity.

The structure of public spending has also undergone a big shift, especially in countries with Spartan welfare states to begin with. The United Kingdom, in a matter of months, designed a European-style wage subsidy from scratch. The United States allowed people to lose their jobs, but sharply boosted unemployment benefits. And every advanced economy has put in place extraordinarily generous loan programs for businesses, in some cases taking all credit risk off banks’ hands. In many countries, the state is back in a big way, and this shift is qualitative as well as quantitative: governments are taking on risks previously borne by the private sector.

Some of these policy shifts are unprecedented. Others are an acceleration of preexisting trends. A reset of several fundamental premises for central bank policymaking had already emerged from the sluggish recovery after the global financial crisis. Central banks largely, if grudgingly, accepted mounting evidence that low interest rates are here to stay. The Federal Reserve, in particular, has embraced a greater tolerance for “running the economy hot,” no longer worrying that inflation might threaten as soon as unemployment comes down. Both shifts in thinking have helped central banks act early and comprehensively to sustain demand, cheap funding, and financial market functioning in the pandemic—a dovish shift in central bank thinking that is likely to continue.

Then there is the significant change in technology used by companies, which suggests that new remote work practices are here to stay. Surveys suggest that many companies plan to retain at least some work-from-home practices even after the pandemic. In any case, the technological and organizational know-how employers have had no choice but to accumulate at breakneck speed this year cannot be unlearned. It almost certainly will create permanent change in how people work.

And this holds not just for employers, but for consumption patterns. The pickup in online retail and substitution of online connectivity for physical travel are unlikely ever to be fully reversed, even if a vaccine eliminates the virus. A dramatic restructuring of the economy is underway.

These changes are easier to respond to in richer than in poorer economies. But there are opportunities even for lower-income economies. If nothing else, policy revolutions in rich countries will be a learning experience for the world and ought to affect the policy conditions attached to financial aid and debt relief for the poorest economies. And some developments provide direct opportunities for emerging economies: the embrace of remote working improves the prospect of attracting outsourced high-value-added service jobs.

Revolutionary questions

Ordinarily, policymakers can at most hope to tweak their governing systems. Mostly their job is to keep things running. At rare moments, however, leaders’ decisions help reset the course of their societies for a long time. This is such a moment.

Leaders now face three big questions about how they envisage their countries’ economic future.

The first is: reallocation or restoration? National economies have been knocked out of joint, leaving companies and workers uncertain about the future—whether a job viable before the pandemic will be again, whether a line of business is worth investing in or should be wound down. The nudge—or not—of policy can make a big difference to whether capital and labor shift into new activities or the allocation of economies’ resources retains its precrisis pattern. Even if COVID-19 makes some activities permanently less profitable, reallocation may not happen—or not to the necessary extent—without policies to promote it, because of the risk and uncertainty involved. Even if the existing economic model is broken, a new one will not build itself.

The second, more stirring, question is, “building back better or back to business?” There is a big difference between using the disruption to build something different and wishing to get things back on track as fast as possible. These two orientations lead to different policy considerations—roughly, whether to keep resource reallocation to the minimum necessitated by the pandemic or use the disruption to reengineer the economy more fundamentally. Building back better will demand more of businesses and people—for example, by doubling down on climate change goals or raising pay and work standards, using the dislocation to move to a different path. The alternative “back to business” approach will aim to make as minimal, quick, and painless as possible any adjustment economic agents have to undertake.

The final question is whether states are ready to once again embrace planning—using intervention to consciously shape the economy over time. Having a policy goal of sectoral reallocation, or regional convergence, or “building back better” presupposes some confidence in the ability of the state to coordinate and steer private sector behavior and a willingness to establish a desired destination. The loss of both confidence and will caused planning to fall out of fashion in the 1980s. As a result most governments today are neither used to strategic planning nor all that good at it.

Yet there are signs that planning is back. Climate change, geopolitical upheavals, rapid technological transformations, and now the pandemic have increased pressure on politicians to lead their economies to a better place, rather than simply freeing the animal spirits of the private sector. Even before COVID-19, economics and economic policy advice were becoming increasingly sympathetic to more active intervention to make economies work better.

Most leaders vow to “build back better” and to oversee a reallocation of resources to more COVID-safe, greener, and more productive activities. At least implicitly this entails a commitment to a more active and strategic state role in the economy than most have engaged in recently. Whether many states have the capability, or their leaders the temperament, to govern the economy more actively and more strategically than before, we are about to find out.

Wealth and Income Distribution: New Theories Needed for a New Era

Growth theories traditionally focus on the Kaldor-Kuznets stylised facts. Ravi Kanbur and Nobelist Joe Stiglitz argue that these no longer hold; new theory is needed. The new models need to drop competitive marginal productivity theories of factor returns in favour of rent-generating mechanism and wealth inequality by focusing on the ‘rules of the game.’ They also must model interactions among physical, financial, and human capital that influence the level and evolution of inequality. A third key component will be to capture mechanisms that transmit inequality from generation to generation.

Six decades ago, Nicholas Kaldor (1957) put forward a set of stylized facts on growth and distribution for mature industrial economies. The first and most prominent of these was the constancy of the share of capital relative to that of wealth in national income. At about the same time, Simon Kuznets (1955) put forward a second set of stylized facts — that while the interpersonal inequality of income distribution might increase in the early stages of development, it declines as industrialized economies mature.

These empirical formulations brought forth a generation of growth and development theories whose object was to explain the stylised facts. Kaldor himself presented a growth model which claimed to produce outcomes consistent with constancy of factor shares, as did Robert Solow. Kuznets also developed a model of rural-urban transition consistent with his prediction, as did many others (Kanbur 2012).

Kaldor-Kuznets Facts No Longer Hold

However, the Kaldor-Kuznets stylized facts no longer hold for advanced economies. The share of capital as conventionally measured has been on the rise, as has interpersonal inequality of income and wealth. Of course, there are variations and subtleties of data and interpretation, and the pattern is not uniform. But these are the stylized facts of our time. Bringing these facts centre stage has been the achievement of research leading up to Piketty (2014).

It stands to reason that theories developed to explain constancy of factor shares cannot explain a rising share of capital. The theories developed to explain the earlier stylized facts cannot very easily explain the new trends, or the turnaround. At the same time, rising inequality has opened once again a set of questions on the normative significance of inequality of outcomes versus inequality of opportunity. New theoretical developments are needed for positive and normative analysis in this new era.

What sort of new theories? In the realm of positive analysis, Piketty has himself put forward a theory based on the empirical observation that the rate of return to capital, r, systematically exceeds the rate of growth, g; the famous r > g relation. Much of the commentary on Piketty’s facts and theorizing has tried to make the stylized fact of rising share of capital consistent with a standard production function F (K, L) with capital ‘K’ and labour ‘L’. But in this framework a rising share of capital can be consistent with the other stylised fact of rising capital-output ratio only if the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour is greater than unity, which is not consistent with the broad empirical findings (Stiglitz, 2014a). Further, what Piketty and others measure as wealth ‘W’ is a measure of control over resources, not a measure of capital K, in the sense that that is used in the context of a production function.

Differences between K and W

There is a fundamental distinction between capital K, thought of as physical inputs to production, and wealth W, thought of as including land and the capitalized value of other rents which give command over purchasing power. This distinction will be crucial in any theorizing to explain the new stylized facts. ‘K’ can be going down even as ‘W’ increases; and some increases in W may actually lower economic productivity. In particular, new theories explaining the evolution of inequality will have to address directly changes in rents and their capitalized value (Stiglitz 2014). Two examples will illustrate what we have in mind.

As demand for these properties rises, perhaps from rich foreigners seeking a refuge for their funds, the value of sea frontage will be bid up. The current owners will get rents from their ownership of this fixed factor. Their wealth will go up and their ability to command purchasing power in the economy will rise correspondingly. But the actual physical input to production has not increased. All else constant, national output will not rise; there will only be a pure distributional effect.

This contingent support to income flows from ownership of bank shares will be capitalised into the value of these shares. Of course, there is an equal and opposite contingent liability on all others in the economy, in particular on workers — the owners of human capital. Again, without any necessary impact on total output, the political economy has created rents for share owners, and the increase in their wealth will be reflected in rising inequality. One can see this without going through a conventional production function analysis. Of course, the rents once created will provide further resources for rentiers to lobby the political system to maintain and further increase rents. This will set in motion a spiral of increasing inequality, which again does not go through the production system at all — except to the extent that the associated distortions represent a downward shift in the productivity of the economy (at any level of inputs of ‘K’ and labour).

Analysing the role of land rents in increases in inequality can be done in a variant of standard neoclassical models — by expanding inputs to include land; but explaining increase in inequality as a result of an increase in other forms of rent will need a theory of rents which takes us beyond the competitive determination of factor rewards.

Differences in Inequality: Capital Income versus Labour Income

The translation from factor shares to interpersonal inequality has usually been made through the assumption that capital income is more unequally distributed than labour income. Inequality of capital ownership then translates into inequality of capital income, while inequality of income from labour is assumed to be much smaller. The assumption is made in its starkest form in models where there are owners of capital who save and workers who do not.

These stylised assumptions no longer provide a fully satisfactory explanation of income inequality because: (i) there is more widespread ownership of wealth through life cycle savings in various forms including pensions; and (ii) increasingly unequal returns to increasingly unequally distributed human capital has led to sharply rising inequality of labour income.

Sharply rising inequality of labour income focuses attention on inequality of human capital in its most general sense:

Discrimination continues to play a role, not only in the determination of factor returns given the ownership of assets, including human capital; but also on the distribution of asset ownership.

An exploration of this type of inequality requires a different type of empirical and theoretical analysis from the conventional macro-level analysis of production functions and factor shares (Heckman and Mosso, 2014, Stiglitz, 2015).

In particular, intergenerational transmission of inequality is more than simple inheritance of physical and financial wealth. Layered upon genetic inequalities are the inequalities of parental resources. Income inequality across parents, due to inequality of income from physical and financial capital on the one hand, and inequality due to inequality of human capital on the other, is translated into inequality of financial and human capital of the next generation. Human capital inequality perpetuates itself through intergenerational transmission just as wealth inequality caused by politically created rents perpetuates itself.

Given such transmission across generations, it can be shown that the long-run, ‘dynastic’ inequality will also be higher (Kanbur and Stiglitz 2015). Although there have been advances in recent years, we still need fully developed theories of how the different mechanisms interact with each other to explain the dramatic rises in interpersonal inequality in advanced economies in the last three decades.1

High Inequality: New Realities and Old Debates

The new realities of high inequality have revived old debates on policy interventions and their ethical and economic rationale (Stiglitz 2012). Standard analysis which balances the tradeoff between efficiency and equity would suggest that taxation should now become more progressive to balance the greater inherent inequality against the incentive effects of progressive taxation (Kanbur and Tuomala,1994 ).

One counter argument is that what matters is not inequality of ‘outcome’ but inequality of ‘opportunity’. According to this argument, so long as the prospects are the same for all children, the inequality of income across parents should not matter ethically. What we should aim for is equality of opportunity, not income equality. However, when income inequality across parents translates into inequality of prospects across children, even starting in the womb, then the distinction between opportunity and income begins to fade and the case for progressive taxation is not undermined by the ‘equality of opportunity’ objective (Kanbur and Wagstaff 2015).

Concluding Remarks

Thus, the new stylised facts of our era demand new theories of income distribution.

This will entail a greater focus on the ‘rules of the game.’ (Stiglitz et al 2015).

References

Bevan, D and J E Stiglitz (1979), “Intergenerational Transfers and Inequality”, The Greek Economic Review, 1(1), August, pp. 8-26.

Heckman, J and S Mosso (2014), “The Economics of Human Development and Social Mobility”, Annual Reviews of Economics, 6: 689-733.

Kaldor, N (1957), “A Model of Economic Growth”, The Economic Journal, 67(268): 591-624.

Kanbur, R (2012), “Does Kuznets Still Matter?” in S. Kochhar (ed.), Policy-Making for Indian Planning: Essays on Contemporary Issues in Honor of Montek S. Ahluwalia, Academic Foundation Press, pp. 115-128, 2012.

Kanbur, R and J E Stiglitz (2015), “Dynastic Inequality, Mobility and Equality of Opportunity“, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 10542.

Kanbur, R and M Tuomala (1994), ‘‘Inherent Inequality and the Optimal Graduation of Marginal Tax Rates”, (with M. Tuomala), Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 96, No. 2, pp. 275-282, 1994.

Kuznets, S (1955), “Economic Growth and Income Inequality”, The American Economic Review, 45(1): 1-28.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Piketty, T, E Saez, and S Stantcheva (2011), “Taxing the 1%: Why the top tax rate could be over 80%”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Roemer, J E and A Trannoy (2014), “Equality of Opportunity”, in A B Atkinson and F Bourguignon (eds.) Handbook of Income Distribution SET Vols 2A-2B. Elsevier.

Stiglitz, J E, et. al. (2015) “Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy“, Roosevelt Institute.

Stiglitz, J E (1969), “Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, Econometrica, 37(3), July, pp. 382-397. (Presented at the December 1966 meetings of the Econometric Society, San Francisco.)

Stiglitz, J E (2012), The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, New York: W.W. Norton.

Stiglitz, J E (2014), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals”, paper presented to the International Economic Association World Congress, Dead Sea, June and forthcoming in Inequality and Growth: Patterns and Policy, Volume 1: Concepts and Analysis, to be published by Palgrave MacMillan.

Stiglitz, J E (2015), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth Among Individuals: Parts I-IV”, NBER Working Papers 21189-21192, May.

Footnotes

1 For early discussions of such transmission processes, see Stiglitz(1969) and Bevan and Stiglitz (1979).

2 Developments in this area are exemplified by Roemer and Trannoy (2014).

Source: