Archive

Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession

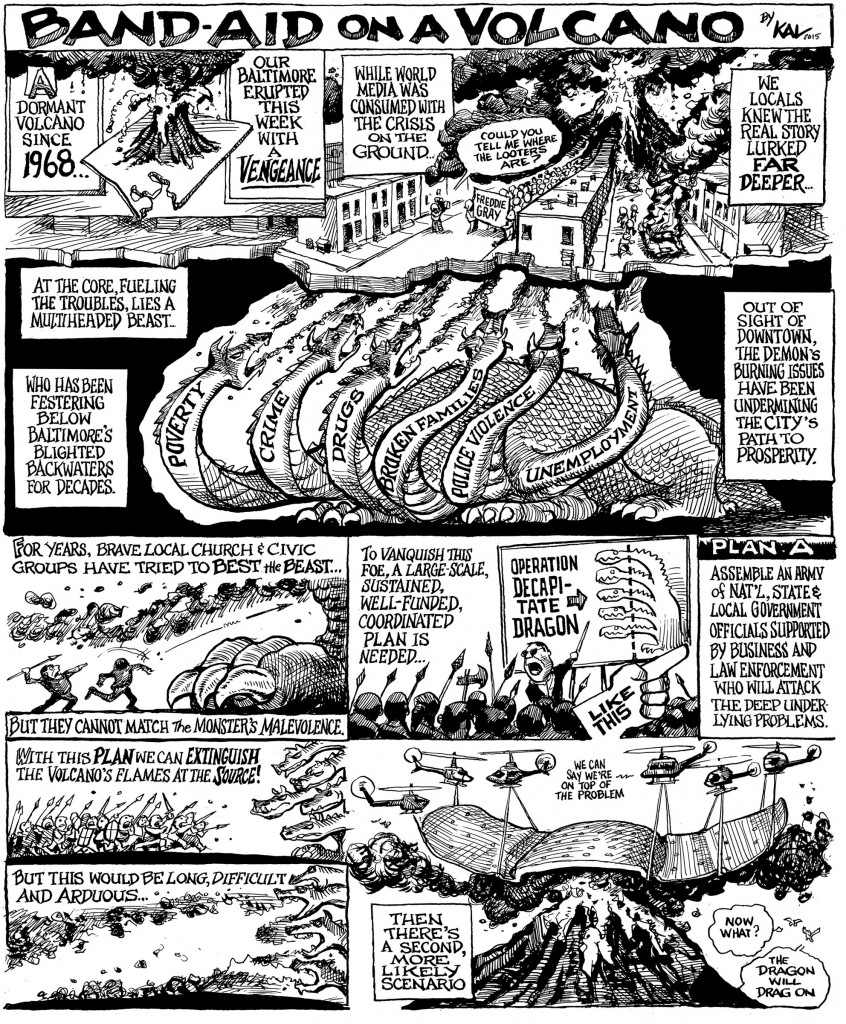

Since 1988, rapid growth in Asia has lifted billions out of poverty. Incomes at the very top of the world income distribution have also grown rapidly, whereas median incomes in rich countries have grown much more slowly. This posting asks whether these developments, while reducing global income inequality overall, might undermine democracy in rich countries.

The period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Great Recession saw probably the most profound reshuffle of individual incomes on the global scale since the Industrial Revolution. This was driven by high growth rates of populous and formerly poor or very poor countries like China, Indonesia, and India; and, on the other hand, by the stagnation or decline of incomes in sub-Saharan Africa and post-communist countries as well as among poorer segments of the population in rich countries.

Anand and Segal (2008) offer a detailed review of the work on global income inequality. In Lakner and Milanovic (2013), we address some of the limitations of these earlier studies and present new results from detailed work on household survey data from about 120 countries over the period 1988–2008. Each country’s distribution is divided into ten deciles (each decile consists of 10% of the national population) according to their per capita disposable income (or consumption). In order to make incomes comparable across countries and time, they are corrected both for domestic inflation and differences in price levels between countries. It is then possible to observe not only how the position of different countries changes over time – as we usually do – but also how the position of various deciles within each country changes. For example, Japan’s top decile remained at the 99th (2nd highest from the top) world percentile, but Japan’s median decile dropped from the 91st to the 88th global percentile. Or, to take another example, the top Chinese urban decile moved from being in the 68th global percentile in 1988 to being in the 83rd global percentile in 2008, thus leapfrogging in the process some 15% of the world population – equivalent to almost a billion people.

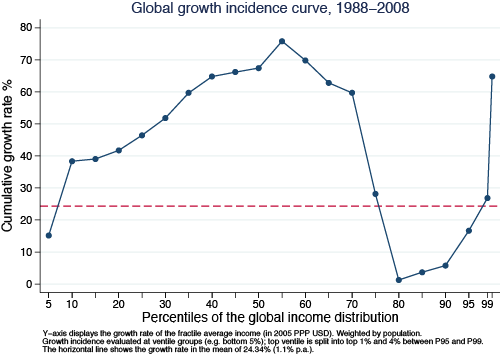

When we line up all individuals in the world, from the poorest to the richest (going from left to right on the horizontal axis in Figure 1), and display on the vertical axis the percentage increase in the real income of the equivalent group over the period 1988–2008, we generate a global growth incidence curve – the first of its kind ever, because such data at the global level were not available before. The curve has an unusual supine S shape, indicating that the largest gains were realised by the groups around the global median (50th percentile) and among the global top 1%. But after the global median, the gains rapidly decrease, becoming almost negligible around the 85th–90th global percentiles and then shooting up for the global top 1%. As a result, growth in the income of the top ventile (top 5%) accounted for 44% of the increase in global income between 1988 and 2008.

Fortunes of income deciles in different countries over time

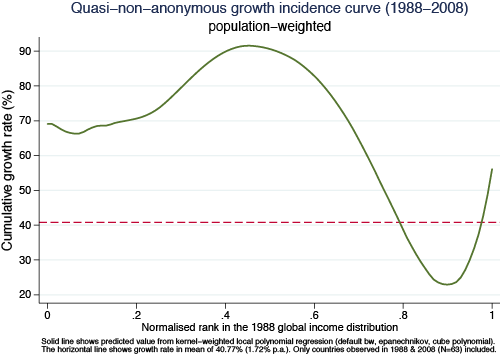

The curve in Figure 1 is drawn using a simple comparison of real income levels at given percentiles of the global income distribution in 1988 and 2008. It is ‘anonymous’ because it does not tell us what happened to the actual people who were at given global income percentiles in the initial year, 1988. In fact, the regional composition of the different global income groups changed radically over time because growth was uneven across regions. A ‘quasi non-anonymous’ growth incidence curve in Figure 2 adjusts for this – the growth rates are calculated for all individual country/deciles at the positions they held in the initial year (1988). The growth rate on the vertical axis (calculated from a non-parametric fit) thus shows how the country/deciles that were poor, middle-class, rich, etc. in 1988 performed over the next 20 years. The supine S shape still remains, although it is now slightly less dramatic.

People around the median almost doubled their real incomes. Not surprisingly, 9 out of 10 such ‘winners’ were from the ‘resurgent Asia’. For example, a person around the middle of the Chinese urban income distribution saw his or her 1988 real income multiplied by a factor of almost 3; someone in the middle of the Indonesian or Thai income distribution by a factor of 2, Indian by a factor of 1.4, etc.

It is perhaps less expected that people who gained the least were almost entirely from the ‘mature economies’ – OECD members that include also a number of former communist countries. But even when the latter are excluded, the overwhelming majority in that group of ‘losers’ are from the ‘old, conventional’ rich world. But not just anyone from the rich world. Rather, the ‘losers’ were predominantly the people who in their countries belong to the lower halves of national income distributions. Those around the median of the German income distribution have gained only 7% in real terms over 20 years; those in the US, 26%. Those in Japan lost out in real terms.

The particular supine S-shaped growth incidence curve (Figure 1) does not allow us to immediately tell whether global inequality might have gone up or down because the gains around the median (which tend to reduce inequality) may be offset by the gains of the global top 1% (which tend to increase inequality). On balance, however, it turns out that the first element dominates, and that global inequality – as measured by most conventional indicators – went down. The global Gini coefficient fell by almost 2 Gini points (from 72.2 to 70.5) during the past 20 years of globalisation. Was it then all for the better?

Probably yes, but not so simply. The striking association of large gains around the median of the global income distribution – received mostly by the Asian populations – and the stagnation of incomes among the poor or lower middle classes in rich countries, naturally opens the question of whether the two are associated. Does the growth of China and India take place on the back of the middle class in rich countries? There are many studies that, for particular types of workers, discuss the substitutability between rich countries’ low-skilled labour and Asian labour embodied in traded goods and services or outsourcing. Global income data do not allow us to establish or reject the causality. But they are quite suggestive that the two phenomena may be related.

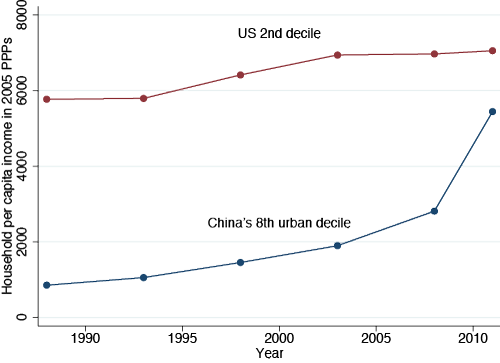

A dramatic way to see the change brought by globalisation is to compare the evolution over time of the 2nd US income decile with (say) the Chinese urban 8th decile (Figure 3). Indeed we are comparing relatively poor people in the US with relatively rich people in China, but given the income differences between the two countries, and that the two groups may be thought to be in some kind of global competition, the comparison makes sense. Here we extend the analysis to 2011, using more recent and preliminary data. While the real income of the US 2nd decile has increased by some 20% in a quarter century, the income of China’s 8th decile has been multiplied by a factor of 6.5. The absolute income gap, still significant five years ago, before the onset of the Great Recession, has narrowed substantially.

Political Implications

And even if the causality cannot be established because of many technical difficulties and an inability to define credible counterfactuals, the association between the two cannot pass unnoticed. What, then, are its implications? First, will the bottom incomes of the rich countries continue to stagnate as the rest of China, or later Indonesia, Nigeria, India, etc. follow the upward movement of Chinese workers through the ranks of the global income distribution? Does this imply that the developments that are indeed profoundly positive from the global point of view may prove to be destabilising for individual rich countries?

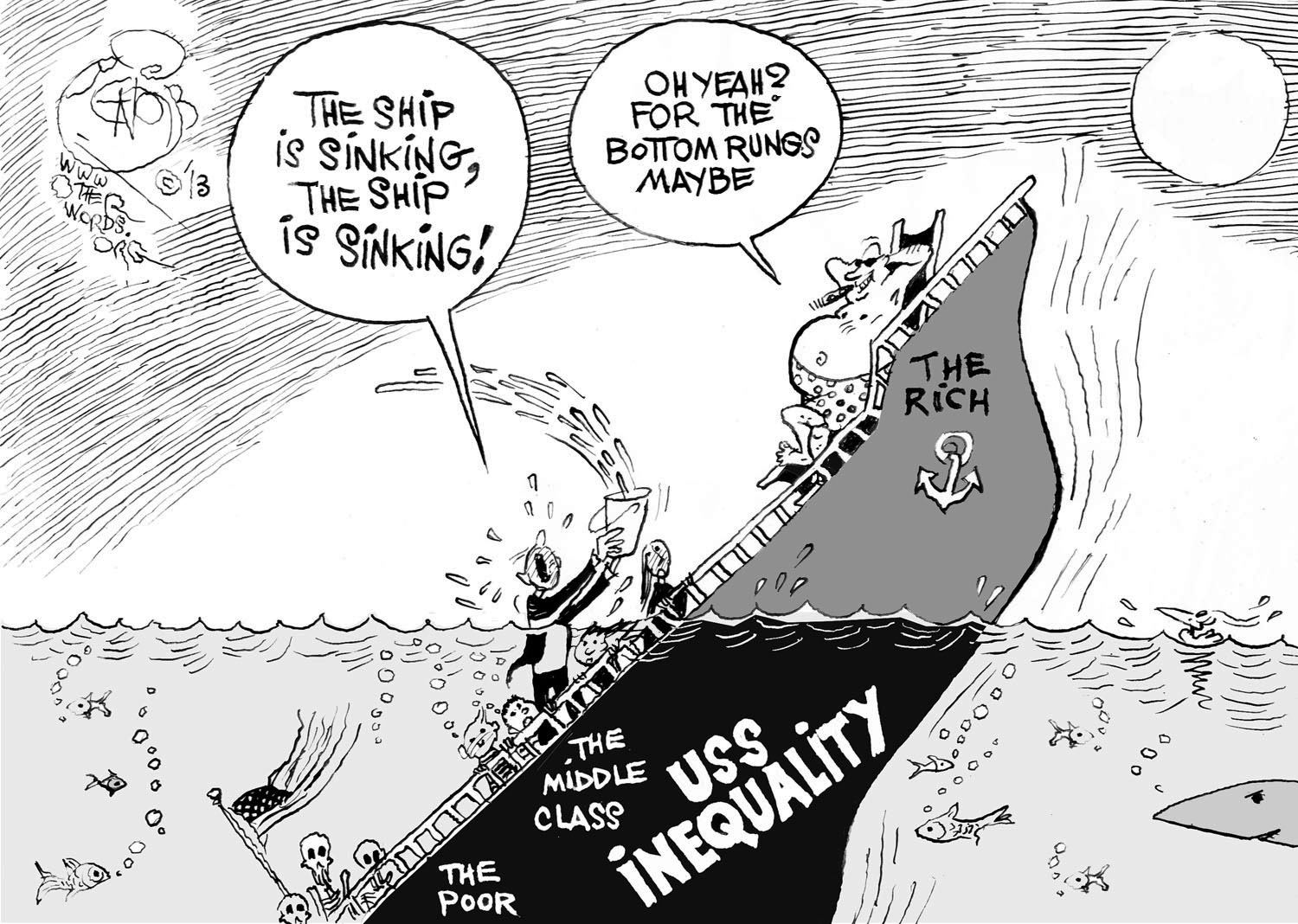

Second, if we take a simplistic, but effective, view that democracy is correlated with a large and vibrant middle class, its continued hollowing-out in the rich world would, combined with growth of incomes at the top, imply a movement away from democracy and towards forms of plutocracy. Could then the developing countries, with their rising middle classes, become more democratic and the US, with its shrinking middle class, less?

Third, and probably the most difficult: What would such movements, if they continue for a couple of decades, imply for global stability? The formation of a global middle class, or the already perceptible ‘homogenisation’ of the global top 1%, regardless of their nationality, may be both deemed good for world stability and interdependency, and socially bad for individual countries as the rich get ‘delinked’ from their fellow citizens.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, the movements that we witness do not only lead to an economic rebalancing of the East and West – in which both may end up with global output shares close to what they had before the Industrial Revolution – but to a contradiction between the current world order, where political power is concentrated at the level of the nation-state, and the economic forces of globalization which have gone far beyond it.

References

Anand, Sudhir and Paul Segal (2008), “What Do We Know about Global Income Inequality?”, Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1): 57–94.

Lakner, Christoph and Branko Milanovic (2013), “Global income distribution: from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession”, World Bank Working Paper No. 6719, December.

Can Democracy Help with Inequality?

Inequality is currently a prominent topic of debate in Western democracies. In democratic countries, we might expect rising inequality to be partially offset by an increase in political support for redistribution. This column argues that the relationship between democracy, redistribution, and inequality is more complicated than that. Elites in newly democratized countries may hold on to power in other ways, the liberalization of occupational choice may increase inequality among previously excluded groups, and the middle classes may redistribute income away from the poor as well as the rich.

There is a great deal of concern at the moment about the consequences of rising levels of inequality in North America and Western Europe. Will this lead to an oligarchisation of the political system, and imperil political and social stability? Many find such dynamics puzzling given that it is happening in democratic countries. In democratic societies, there ought to be political mechanisms that can inhibit or reverse large rises in inequality, most likely through the fiscal system. Indeed, one of the most central models in political economy, due originally to Meltzer and Richard (1981), suggests that high inequality in a democracy should lead the politically powerful (in their model the voter at the median of the income distribution) to vote for higher levels of taxes and redistribution, which would partially offset rising inequality.

But before asking about what happens in a democracy, we could start with some even more fundamental questions. Is it correct factually that democracies redistribute more income than dictatorships? When a country becomes democratic, does this tend to increase redistribution and reduce inequality? The existing scholarship on these questions, though vast, is quite contradictory. Historical studies, such as Acemoglu and Robinson (2000) and Lindert (2004), tend to suggest that democratization increases redistribution and reduces inequality. Using cross-national data, Gil et al. (2004) find no correlation between democracy as measured by the Polity score and any government spending or policy outcome. The evidence on the impact of democracy on inequality is similarly puzzling. An early survey by Sirowy and Inkeles (1990) concludes, “the existing evidence suggests that the level of political democracy as measured at one point in time tends not to be widely associated with lower levels of income inequality” (p. 151), though Rodrik (1999) finds that both the Freedom House and Polity III measures of democracy were positively correlated with average real wages in manufacturing and the share of wages in national income (in specifications that also control for productivity, GDP per capita, and a price index).

In a recent working paper (Acemoglu et al. 2013), we revisit these questions both theoretically and empirically.

Theoretical Nuances

Theoretically, we point out why the relationship between democracy, redistribution, and inequality may be more complex than the discussion above might suggest. First, democracy may be ‘captured’ or ‘constrained’. In particular, even though democracy clearly changes the distribution of de jure power in society, policy outcomes and inequality depend not just on the de jure but also the de facto distribution of power. Acemoglu and Robinson (2008) argue that, under certain circumstances, elites who see their de jure power eroded by democratization may sufficiently increase their investments in de facto power (e.g. via control of local law enforcement, mobilization of non-state armed actors, lobbying, and other means of capturing the party system) in order to continue to control the political process. If so, we would not see much impact of democratization on redistribution and inequality. Similarly, democracy may be constrained by other de jure institutions such as constitutions, conservative political parties, and judiciaries, or by de facto threats of coups, capital flight, or widespread tax evasion by the elite.

Democratization can also result in ‘inequality-increasing market opportunities’. Non-democracy may exclude a large fraction of the population from productive occupations (e.g. skilled occupations) and entrepreneurship (including lucrative contracts), as in Apartheid South Africa or the former Soviet Union. To the extent that there is significant heterogeneity within this population, the freedom to take part in economic activities on a more level playing field with the previous elite may actually increase inequality within the excluded or repressed group, and consequently the entire society.

Finally, consistent with Stigler’s ‘Director’s Law’ (1970), democracy may transfer political power to the middle class, rather than the poor. If so, redistribution may increase and inequality may be curtailed only if the middle class is in favour of such redistribution.

But what are the basic robust facts, and do they support any of these mechanisms?

Empirical Evidence

Cross-sectional (cross-national) regressions, or regressions that do not control for country fixed effects, will be heavily confounded with other factors likely to be simultaneously correlated with democracy and inequality. In our work we therefore focus on a consistent panel of countries, and investigate whether countries that become democratic redistribute more and reduce inequality relative to others. We also focus on a consistent definition of democratization based on Freedom House and Polity indices, building on the work by Papaioannou and Siourounis (2008).

One of the problems of these indices is the significant measurement error, which creates spurious movements in democracy. To minimize the influence of such measurement error, we create a dichotomous measure of democracy using information from both the Freedom House and Polity data sets, as well as other codings of democracies, to resolve ambiguous cases. This leads to a binary measure of democracy for 184 countries annually from 1960 (or post-1960 year of independence) to 2010. We also pay special attention to modeling the dynamics of our outcomes of interest – taxes as a percentage of GDP, and various measures of structural change and inequality.

Our empirical investigation uncovers a number of interesting patterns. First, we find a robust and quantitatively large effect of democracy on tax revenues as a percentage of GDP (and also on total government revenues as a percentage of GDP). The long-run effect of democracy in our preferred specification is about a 16% increase in tax revenues as a fraction of GDP. This pattern is robust to various different econometric techniques and to the inclusion of other potential determinants of taxes, such as unrest, war, and education.

Second, we find an effect of democracy on secondary school enrolment and the extent of structural transformation (e.g. an impact on the nonagricultural shares of employment and output).

Third, however, we find a much more limited effect of democracy on inequality. Even though some measures and some specifications indicate that inequality declines after democratization, there is no robust pattern in the data (certainly nothing comparable to the results on taxes and government revenue). This may reflect the poorer quality of inequality data. But we also suspect it may be related to the more complex, nuanced theoretical relationships between democracy and inequality pointed out above.

Fourth, we investigate whether there are heterogeneous effects of democracy on taxes and inequality consistent with these more nuanced theoretical relationships. The evidence here points to an inequality-increasing impact of democracy in societies with a high degree of land inequality, which we interpret as evidence of (partial) capture of democratic decision-making by landed elites. We also find that inequality increases following a democratisation in relatively nonagricultural societies, and also when the extent of disequalising economic activities is greater in the global economy as measured by US top income shares (though this effect is less robust). These correlations are consistent with the inequality-inducing effects of access to market opportunities created by democracy. We also find that democracy tends to increase inequality and taxation when the middle class are relatively richer compared to the rich and poor. These correlations are consistent with Director’s Law, which suggests that democracy allows the middle class to redistribute from both the rich and the poor to itself.

Conclusions

These results do suggest that some of our basic intuitions about democracy are right – democracy does represent a real shift in political power away from elites that has first-order consequences for redistribution and government policy. But the impact of democracy on inequality may be more limited than one might have expected.

This might be because recent increases in inequality are ‘market-induced’ in the sense of being caused by technological change. But at the same time, our work also suggests reasons why democracy may not counteract inequality. Most importantly, this may be because, as in the Director’s Law, the middle classes use democracy to redistribute to themselves. Nevertheless, since the increase in inequality in the US has been associated with a significant surge in the share of income accruing to the very rich, compared to both the middle class and the poor, Director’s Law-type mechanisms seem unlikely to be able to explain why policy has not changed to counteract this. Clearly other political mechanisms must be at work, the nature of which requires a great deal of research.

References

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson (2000), “Why Did the West Extend the Franchise?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115: 1167–1199.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson (2008), “Persistence of Power, Elites and Institutions”, The American Economic Review, 98: 267–291.

Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A Robinson (2013), “Democracy, Redistribution and Inequality”, NBER Working Paper 19746.

Gil, Ricard, Casey B Mulligan, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin (2004), “Do Democracies have different Public Policies than Nondemocracies?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18: 51–74.

Lindert, Peter H (2004), Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth since the Eighteenth Century, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Meltzer, Allan M and Scott F Richard (1981), “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government”, Journal of Political Economy, 89: 914–927.

Papaioannou, Elias and Gregorios Siourounis (2008), “Democratisation and Growth”, Economic Journal, 118(532): 1520–1551.

Rodrik, Dani (1999), “Democracies Pay Higher Wages”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114: 707–738.

Sirowy, Larry and Alex Inkeles (1990), “The Effects of Democracy on Economic Growth and Inequality: A Review”, Studies in Comparative International Development, 25: 126–157.

Stigler, George J (1970), “Director’s Law of public income redistribution”, Journal of Law and Economics, 13: 1–10.

Economics Can’t Avoid Distributional Issues

Economics can’t avoid distributional issues—it must make room for insights from other disciplines

We live in an age of material abundance and social disquietude. A quarter millennium of industrial revolution has produced an awesome increase in prosperity: almost 8 billion people and enough wealth for every one of them to live lives of unprecedented comfort. The problem, of course, is in the distribution.

The rise of economic inequality in the developed world is weighing on growth and straining the fabric of liberal democracy. And economists, who exert a profound influence on public policymaking, have an important role to play in analyzing the inequities of distribution, exploring the consequences, and shaping remedies. The past half century has provided a mountain of data. And in the past decade, particularly among younger economists, there has been a clear surge of interest and engagement.

Just as economists learned to incorporate the growth of knowledge into their understanding of the world, just as they have—for the most part—accepted the need to wrestle with the imperfections of financial markets, so too they now are grappling in earnest with the complexities of distributional questions.

Yet as a careful observer of the discipline of economics—albeit as an outsider looking in through the windows—engagement with these questions seems to me still constrained by a number of factors. Many economists have enduring doubts about the importance of distributional issues. Many are reluctant to become engaged in what they see as normative questions. And intertwined with these doubts and misgivings is the discipline’s disregard for other forms of knowledge, and its lack of diversity.

The field’s long-standing indifference to the distribution of prosperity has come at the particular expense of minorities, and it is no great leap to suggest that a more diverse profession might reach different conclusions. To be sure, this is a premise that offends some economists. Milton Friedman famously insisted that the political views of good economists could not be discerned in their academic work. He lacked the self-awareness to see that his interests, methods, and conclusions were all informed by his life experience—and in this respect, Friedman was just like everyone else.

In some cases, greater diversity may yield greater clarity. In other cases, greater diversity may result in greater confusion, as new voices challenge old certitudes. But that is a kind of clarity too: it will tell us what we don’t know.

Equity vs Efficiency

Inequality is an economic issue. A growing body of research illuminates its importance. The distribution of wealth and income has a meaningful influence on the distribution of opportunity, on the mechanics of the business cycle, and on the pace of innovation. Inequality also distorts public policy, increasing the power of rent-collecting elites and of those seeking aid, while attenuating the sense of shared purpose necessary for public investment in education, infrastructure, and research.

For decades, mainstream economists argued that efforts to address inequality through redistributive policies would come at the expense of growth—what Arthur Okun called “The Big Tradeoff.” But one silver lining to the rise of inequality over the past half century has been the opportunity to study the real-world impact. A number of recent studies, including work by Jonathan D. Ostry and his colleagues at the IMF (Ostry, Loungani, and Berg 2019), find that high levels of inequality actually impede growth.

Yet even among economists who regard this evidence as compelling, one encounters hesitation about incorporating distributional considerations into the advice professors give to policymakers. Economists have long conceived of their role in public policy debates as being “the partisan advocate for efficiency,” in the words of Charles Schultze, an advisor to Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Jimmy Carter. One reason is that in championing efficiency, economists think of themselves as representing the interests of the common man and woman. “Without economists in the room, it’s like a free-for-all where everybody is going for their narrow self-interest and there is no voice for efficiency. And what ‘efficiency’ really means is ‘every American citizen,’” said Michael Greenstone, a University of Chicago economist who worked in the Obama administration. The evidence of the past half century strongly suggests that simply advocating for efficiency does not produce the best outcomes for those ordinary men and women. But there is real value in the role, there isn’t anyone else likely to perform it, and therefore it’s reasonable to have some hesitation about the consequences of a diluted focus.

The field’s long-standing indifference to the distribution of prosperity has come at the particular expense of minorities.

Furthermore, many economists profess a reluctance to meddle in what they regard as a political debate about the distribution of economic output. Quite often, the result is that economists finesse the question of distribution by noting that the benefits of more efficient policy could be distributed equitably, whatever that means, but the details should be worked out by the politicians. Paul Romer, a Nobel laureate in economics, argued in a recent essay (Romer 2020) that economists should just “say ‘No’ when government officials look to economists for an answer to a normative question.”

I recognize the appeal of Romer’s advice. Overconfidence is a common attribute in disciplines that reach for practical conclusions. Perhaps it is even a necessary one: after all, choices must be made. But there is an obvious attraction in limiting the scope of the potential damage.

The problem is that normative judgments can’t be avoided.

In the 1980s, for example, most mainstream economists favored the elimination of minimum wage laws. In 1987, my predecessors at the New York Times editorialized in favor of eliminating minimum wage laws, citing “a virtual consensus among economists that the minimum wage is an idea whose time has passed.” This was purely a judgment about economic efficiency. Economists did not pretend to weigh other arguments for minimum wages. But by advocating for a change in policy on the basis of efficiency, they implicitly devalued those arguments. (And, as it happened, even the efficiency argument was wrong. A few years later, two economists took the radical step of gathering evidence and reached a different conclusion. American workers are still suffering the consequences.)

Even economists who embrace in good faith the argument for avoiding distributional advice—especially economists who embrace this argument in good faith—must recognize that, in practice, they are facilitating the exclusion of distributional issues from public debate. A genuine concern about distributional issues requires distribution to be treated as a primary goal of policy, not as a by-product that requires remediation.

It is particularly problematic for economists to advocate for a policy as broadly beneficial if there is no mechanism for a broad distribution of benefits. Economists have often advocated for trade deals by calculating net benefits and deferring questions of distribution. But the second act seldom happens. “The argument was always that the winners could compensate the losers,” the economist Joseph Stiglitz, also a Nobel laureate, told me a few years ago. “But the winners never do.” Huffy, for example, built about 2 million bikes a year in the town of Celina, Ohio, until it moved production to China in 1998 to meet Walmart’s demand for cheaper bikes. There is now a Walmart where the Huffy workers once parked their cars, and everyone in Celina—and everyone in towns across the United States—can buy cheaper bicycles. But the workers lost their jobs, and promises of help went largely unkept. Advocacy for the interest of “the people,” in the abstract, often ends up looking a lot like cruel indifference to actual people.

Cross-pollination

The assertion here is not that economists should aspire to provide comprehensive guidance on the optimal distribution of economic output. They can’t. Cross-pollination with other disciplines has enriched economics, as in the incorporation of insights from psychology; from the work of demographers who look at the spatial dimension of economic activity; and from the examination of the evolution of economic ideas through time. But the goal ought not to be the creation of some hybrid super social science.

Rather, the need is to leave space for other perspectives. Economists can provide better guidance to policymakers by emphasizing the importance of distribution—and the importance of considering other kinds of knowledge.

Cross-pollination with other disciplines has enriched economics. But the goal ought not to be the creation of some hybrid super social science.

A disturbing body of psychological research, for example, documents that economic inequality mimics the effects of absolute poverty on physical and mental health. This isn’t an insight that fits easily into economic models, nor does it need to. The key question is how to make sure that information is incorporated into decision-making alongside economic analysis.

There’s an old saying that there are two kinds of scientists: those trying to understand the world and those trying to change it. The nature of economics places it solidly in the second category, but economists don’t always seem to recognize the implications. Treating distributional issues as segregable is politically naive and therefore tends to limit the beneficial influence of economic ideas. The development economist Gustav Ranis observed that economists struggled to influence policy in many developing nations because they had their priorities backward. Economists emphasized efficiency as the most important goal of public policy while regarding political stability and distributional equity as benefits of the resulting growth. Ranis argued that the list should be reversed. People must agree that policies are equitable and conducive to stability before they are likely to support measures to increase efficiency.

That’s a powerful truth: no matter how well you think you understand the world, you still need to persuade others to listen.

References:

Boushey, Heather. 2019. Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We Can Do about It. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ostry, Jonathan D., Prakash Loungani, and Andrew Berg. 2019. Confronting Inequality: How Societies Can Choose Inclusive Growth. New York: Columbia University Press.

Payne, Keith B. 2017. The Broken Ladder: How Inequality Affects the Way We Think, Live, and Die. New York: Viking Penguin.

Romer, Paul. 2020. “The Dismal Kingdom: Do Economists Have Too Much Power?” Foreign Affairs (March/April).

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF and its Executive Board, or IMF policy.

The Inequality Paradox: Rising Inequalities Nationally, Diminishing Inequality Worldwide

Workers in emerging economies benefitted from globalization and workers in rich countries, on balance, did not. Overturning globalization, however, will neither work nor bring a real improvement to the Western middle classes.

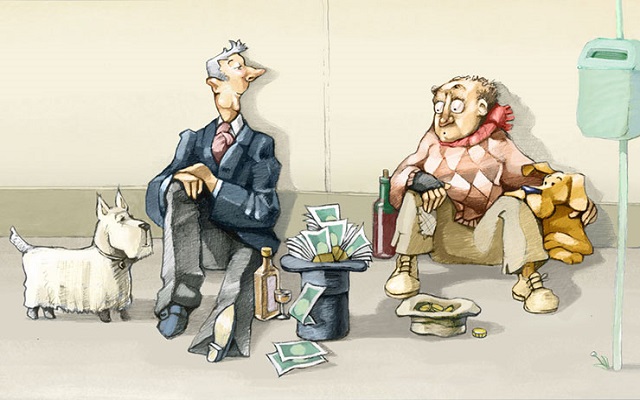

The reason why this article on inequality is being published and the reason why you are reading it is because income and wealth inequalities have risen, often dramatically, in most countries in the world over the past 40 years.

This is a well-known fact which is nevertheless worth emphasizing because the United States is often mistakenly singled out, and the impression is created that such increases were small or non-existent everywhere else. While US inequality did rise substantially—from 34 Gini points at the trough of inequality in 1979 to 41 Gini points in 20161—it was hardly unique.2 Out of seventeen OECD countries for which comparable data are available, fifteen saw an increased inequality in disposable income (that is, income that people receive after social transfers and direct taxes) between the mid-1980s and 2013-15.3

There are some unusual suspects in this group. Israel, which used to be a semi-socialist country, is now as unequal as the United States. Sweden, which some people still see as a paradise of welfare and equality, had the greatest increase of all countries. Denmark, held by Bernie Sanders as the model the United States should emulate, also registered an increase (3 Gini points). Germany, another powerhouse of worker codetermination and collective bargaining, experienced the same increase as Denmark.

And not only did disposable income inequality rise; inequality of market incomes, that is incomes before taxes and transfers, went up by even more. Since market income is composed of wages and property incomes unaffected by direct taxes and social transfers (such as public pensions and welfare), the rise in market income inequality shows that all rich countries were exposed to the same forces of globalization and technological change that tended to push inequality up. At the disposable income level, although inequality went up in all seventeen advanced countries considered here, in some countries it went up less than in others due to differences in economic policy.

A comparison between the United States and Germany is instructive in that regard. The top line in figure 1 shows inequality of market incomes. As can be seen, inequality increased steeply in both countries. Actually, it increased even more steeply in Germany and has recently been at the level of about 55 Gini points in both countries. The bottom line shows what happens to disposable income inequality once social transfers and direct taxes kick in. In both countries, disposable income inequality is less than market income inequality as transfers and taxes help the poor and the middle class.

But the inequality-reducing effect of transfers and taxes is much weaker in the United States. Moreover, until the mid-1990s, their effect was “accommodating” as inequality in both disposable and market incomes went up by about the same amount (shown in parallel upward movements of the two lines in figure 1). In Germany, however, taxes and transfers are more redistributionist, and inequality in disposable income increased significantly less than in market incomes (the bottom line in the figure went up by very little despite the steep rise in the top line).

Why did it happen? In the United States, economic policies until the late 1990s (tax rates, progressiveness of social transfers and the like) remained about the same as they had been when market income inequality was much lower (in the 1970s and 1980s). In other words, policy sometimes accommodated higher inequality rather than offset it. In the case of Germany, policies were deployed to partially curb the rise in market income inequality, and consequently, the bottom line rose much less than the top line.

Thus we come to our first conclusion: While all rich countries were exposed to the same forces of globalization and technological change that tended to push inequality up, and while almost all failed to offset these forces fully, there was still a role for policy. In some cases, policies continued as in the past when the underlying forces of inequality (“the winds of globalization”) were much more benign; in others, pro-poor policies were used to offset them. We shall come back to this conclusion regarding the role of domestic policies.

Rises in inequality were not limited to rich countries. China’s inequality at the beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the late 1970s was very low; presently, it is higher than inequality in the United States. In other words, if increase in inequality in the United States is found worrying, so much more is the rise of inequality in China.

However, China has one big “attenuating” circumstance: Its inequality doubled while its real income per capita increased by more than 20 times. Obviously, it is much easier to find increases in inequality acceptable when everybody’s income goes up, and especially when it does so at a rate as high as it did in China.

That was not the case in Russia where, during the Yeltsin years, real income plummeted (even more than during the Great Depression in the United States), and yet inequality increased vertiginously. Russia became the country where the total combined wealth of billionaires was, measured in terms of country’s GDP, the highest in the world.4 Such an increase in inequality, combined with a much lower overall real income, meant impoverishment for many. The humiliation of the many along with huge wealth for the few is what has led to a rejection of the Yeltsin years and an acceptance of Putin’s form of oligarchy.

In India too, inequality increased after the liberalization reforms of 1991. However, similarly to China, higher inequality was accompanied by higher incomes and was thus socially more bearable. Even, and somewhat incredibly, in post-apartheid South Africa (which at the close of the apartheid era was among the most unequal countries in the world), income inequality increased even further. It is a big political issue, as shown by the weakening power of ANC and the increasing prominence of the extreme left-wing Economic Freedom Fighters.

It is thus not surprising that income inequality had become such an important political issue (Barack Obama called it “the defining issue of our times”). If income differences between people increase, if governments are not seen as able or willing to do much, if many high incomes are the product of monopoly rents or corruption, if the middle class is shrinking, one can hardly be surprised at the political salience of inequality.

But what is, at first sight, paradoxical is that such rising inequalities within nations are accompanied by decreasing global inequality—that is, if we look at inequality across all citizens of the world (more than 7 billion of them) and not merely at inequalities within each nation-state as we have done so far. There, using the same indicator of Gini coefficient, global inequality has gone down from more than 70 points in the mid-1980s to some 65 points today.5 It is still enormous, but it is lower than it used to be. Even the proverbially immensely rich global top 1 percent has seen its share of global income diminish after the global recession, from 22 percent in 2008 to 20.4 percent in 2013.6

How did it happen? The answer is simple: The reduction in global inequality was driven by high income growth in heretofore very poor countries like China, India, Vietnam, and Indonesia where almost everybody had seen their incomes increase at a fast clip—much faster than in the rich world. Thus a sort of “global middle class” has been created.

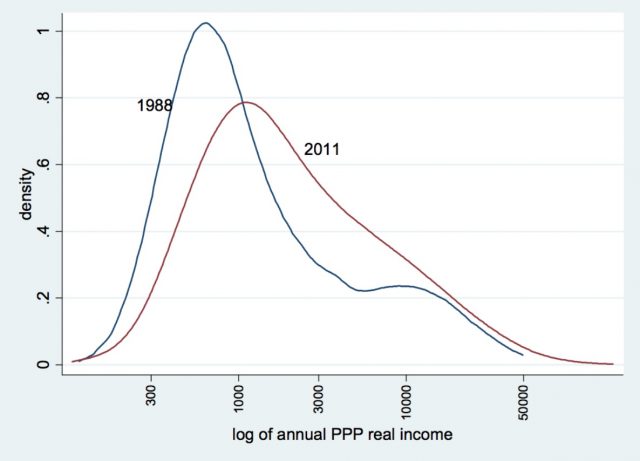

Figure 2 shows this phenomenon through the thickening of the distribution around the middle: There are simply more people in the world with incomes that are around the world median. These are indeed not the people that, in Western perception, would be considered a “middle class” since their incomes are much lower than typical Western middle class incomes, but from the global point of view they are indeed a (large) group sitting right in the middle of the global income distribution and, if the trends continue, likely to move upward. The slowdown of growth (and several years of negative growth) that affected the rich West in the wake of the global recession further helped the convergence of Asian incomes and reduced global income inequality.

Two things are remarkable in the current decline of global income inequality: For the first time in the past 200 years, inequality among world citizens has decreased; and this decrease has taken place while within-national inequalities almost everywhere have gone up. These two facts, translated in terms of winners and losers, mean that workers and the middle classes in emerging economies did well, and workers and the middle classes in the rich world did poorly. Simplifying things a bit, we can say that workers in emerging economies benefitted from globalization and workers in rich countries, on balance, did not. Is there a conflict of interest between the two groups?

The answer is “yes.” And the reason is, I think, obvious. So long as national economies were not fully integrated, and especially so long as several billion workers in China, India, Russia, and elsewhere were not fully part of a global capitalist economy, very different wages for the same kind of labor could be maintained. A French worker was not in direct competition with a Chinese worker. But with globalization, if these two workers produce the same product or have approximately the same skill, they now enter into competition. Whom, if he can choose, is the capitalist going to hire? The answer is obvious: a cheaper worker.

Now, not all workers are in mutual competition: Some are producing so-called non-tradables that cannot be exported or imported (domestic services, legal advice, many medical procedures, etc.), skills of some are complementary to the skills of porer workers (a cheaper Indian accountant would increase the income of a Western self-employed worker), and some are directly competing (Indian and Western accountant, or American and Chinese steelmakers).

What should countries do then? It does not seem that the emerging economies need to do much since, given their wage rates and the type of globalization that exists, things seem to be working to their advantage. This scenario, of course, will not continue forever. As China becomes richer, its wages will rise, and the cost advantage will gradually diminish. We already see the wages of unskilled workers in China rising faster than those of skilled workers, and the gap between Chinese and Western wages is now less than it used to be. But it is also true that China, while the largest country and in that sense the most important competitor of the West, will be followed by other populous and still relatively poor countries like India, Vietnam, Burma, and Ethiopia that could, down the road, present the same competition for Western labor that China does today.

So, the question of what to do poses itself much more forcefully for the rich countries. The knee-jerk answer is to shut down integration and globalization, since those developments are at the origin of the problem. But that intuitive reaction does not take into account that globalization is also at the origin of many income gains in rich countries, that it enables specialization in the areas where countries are more efficient, and that neither slamming of tariffs nor a ban on outsourcing will substantially help domestic workers or overturn the process of globalization that has gone too far. Even the most powerful countries like the United States become “small” when contrasted with the world: It might have been different in the 1950s when US Gross Domestic Product accounted for 40 percent of the world’s output, but today it is only 16 percent.7

Thus, overturning globalization will neither work nor bring a real improvement to the Western middle classes. What will? Only domestic policies whose objective is either direct compensation of those who have lost their jobs, or (much better) greater efforts in matching the new workers’ skills to the demand, and especially in improving the quality and accessibility of education for all. This has been realized to be a problem in the United States where the quality of public education, due to neglect and lack of funds, has deteriorated, and where what used to be probably the best system of public education in the world has slipped much in the rankings (as measured by students’ scores on math and sciences).

There are thus two types of domestic policies that are the remedies for the “ills” of globalization. One is the standard set of redistributionist policies, including higher taxation of the rich and greater benefits for those whose jobs are destroyed. Such policies will allow the bottom line in our figure 1 to remain more or less flat (that is, to register no increase in inequality) even if the underlying inequality (reflected in the top line) continues to go up. They are however merely reactive or palliative policies. The second set of policies that deal with education are more long-term in nature. They will help stop the increase in the top line of figure 1 (market income inequality) by improving skill levels and by better matching the supply and demand of skills. When the increase in the underlying inequality is less, the standard redistributionist policies can be more relaxed too.

But until that happens, both sets of policies should be used: greater direct help for those affected by globalization and longer-term improvements in skills.

Notes

- Calculated from Luxembourg Income Study data, based on US Current Population Survey.

- Gini index, a measure of inequality, ranges from the theoretical value of 0 when all individuals have the same income to an equally theoretical value of 100 when the entire income is received by one person. It is considered that relatively equal countries have Ginis around 30.

- See 2015 OECD report: In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All.

- Calculated from Forbes data.

- Own calculations.

- World Inequality Report 2018.

- Calculated from World Bank data; in Purchasing Power Parity dollars.

Equality, Justice and Other Nonsense

There are different conceptions of “equality”, and “justice”, but only some of these conceptions are commensurate with the institutions of individual liberty, private property, consensual contractualism and personal accountability. This essay argues that classical-liberal thinkers like Adam Smith and John Locke offered superior conceptions of equality and justice than much of the contemporary discourse does. This essay claims that the contemporary use of equality and justice is nonsensical; whereby nonsense is the absence of meaningful denotation and the intentional hiding of subjective normativity.

Sound and Fury

“I have found that words that are loaded with pathos and create a seductive euphoria are most apt to promote nonsense” – The German novelist Günter Grass was not referring neither to equality nor justice in this interview to Der Spiegel on August 20th, 2010. But the warning stands. In the contemporary discourse, both concepts are loaded with pathos. Agents of different persuasion use the seductive euphoria of these terms to promote nonsense, or even worse.

Thomas Piketty, in his 2014 Capital in the Twenty-First Century, is one example. He studies wealth and income inequality in Europe and the US since the 18th century. Piketty claims that inequality is not an accident but rather a feature of capitalism that can be reversed only through state intervention. And further, unless capitalism is reformed, the very democratic order will be threatened. The recipe for capitalism’s reform is a global tax on wealth.

There have been many criticisms of Piketty (2014) for reasons of methodology and his treatment of data, which is rather generous to himself (Sutch 2017, Acemoglu & Robinson 2015). Carlos Góes, an economist with the International Monetary Fund, did not find any empirical confirmation of Piketty’s (2014) central empirical thesis. According to him, when the rate of return on capital (r) is greater than the rate of economic growth (g), over the long term, the result is concentration of wealth. in fact, Góes even identified an opposite trend in 75% of the countries that he studied (Goes 2016).

Nonsense is, in the meaning of this essay, the absence of meaningful denotation and the intentional hiding of subjective normativity. Piketty, in reducing all economic issues to one and not defining his independent variable (capital), puts himself outside the factual, or academic, discourse.

But the most problematic failure of Piketty’s work occurs on a conceptual level. He reduces all economic problems of the past 200 years to inequality. He makes readers think that nothing else matters. Furthermore, he does not define some of his most important concepts, such as capital. Not even the conception of inequality is duly explored: Piketty seems to reduce it to a comparison of results, namely the stocks of (some) capital held by different people. Finally, he does not explore different solutions and their possible impacts on capital itself, its allocation, or distribution. He only suggests one remedy and does not even offer an economic explanation for why or how the tax on wealth reforms capitalism or strengthens the democratic order. Piketty (2014) does also not discuss the impacts of such a tax on private property, contractualism, liberty, and on productivity. To his defense: he does not need to address these issues, because he disregards them. For him, only inequality matters – the rest does not.

Piketty is an example for the nonsensical use of a concept – in this case, equality. Nonsense is, in the meaning of this essay, the absence of meaningful denotation and the intentional hiding of subjective normativity. Piketty, in reducing all economic issues to one and not defining his independent variable (capital), puts himself outside the factual, or academic, discourse. If a model cannot be assessed by a third-party observer and if data can neither be replicated, proven false, nor made plausible, then an argument cannot be convincing by its validity, but only, if anything, by its normativity. Similarly, when Piketty (2014) proposes a wealth-tax without even examining its consequences or alternatives, it becomes clear that his work reflects a personal normative agenda. He uses the concept of equality to hide his normative intentions and to give academic pedigree to his argument.

A similar discourse occurs regarding justice, or its absence. For example, Buchanan & Mathieu (1986) said that “justice is usually said to exist when a person receives that to which he or she is entitled, namely, exactly those benefits and burdens that are due the individual because of his or her particular characteristics and circumstances”. John Rawls’ (1971) theory is that justice is fairness and fairness can be achieved by redistribution. But Rawls is not a crude redistributionist. He echoes Ricardo when he bases his Theory of Justice on two principles. First Principle: Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all. Second Principle: Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both: (a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged, consistent with the just savings principle, and (b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity.

However: What is suspicious of being result-oriented thinking in Rawls’ (1971) case, is clearly normative in Buchanan & Mathieu (1986). Neither seems interested in justice, per se, but in policy-prescription. They hide personal normative agendas behind the concept of justice; they create the impression of their own idea of justice as an objective one. And they rely on the moral intuition attached to that term as well as on its apparent objectivity to legitimize the policies they advocate. In both cases, policies are being suggested without alternatives being evaluated and without the consequences of such policies being studied – at least not the consequences for the individual. Note also that both policy prescriptions heavily rely on institutions – as bureaucratic entities with regulators privileged over the individual – administering these policies. At the same time, neither reviews how institutions in their organizational sense and their structures of incentives and power might contribute in making situations unjust.

Nonsensical Discourse

When this essay claims justice and equality to be nonsense, it understands much of the contemporary discourse about it as nonsensical. Instead of evaluating the conceptions of equality or justice, result-oriented thinking and masked normativity guide the contemporary use of these terms. This might be intellectually dishonest, but it is especially perilous to the institutions – in the sense of the rules of grammar of social interaction – that protect and empower the individual: individual liberty, private property, consensual contractualism, and personal accountability.

The interesting turn of events is that classical liberalism was at the vanguard of the advocacy for equality and justice in the 18th and 19th centuries. Both concepts are central to thinkers such as John Lock, David Hume, or Adam Smith. What happened? Why were these concepts, if anything, valid then, and are invalid, nonsensical, or even destructive now?

They hide personal normative agendas behind the concept of justice; they create the impression of their own idea of justice as an objective one. And they rely on the moral intuition attached to that term as well as on its apparent objectivity to legitimize the policies they advocate.

The problem is not the concept, but the conception, i.e. the set of ideas standing behind the terms. In the past 50 years, the framework of reference for both changed radically. These concepts were appropriated by a specific political normativity. Uncovering the change helps to understand why most contemporary talk about equality and justice is nonsensical in the understanding of this paper. But it also points at how to make sense of them. Looking back at the ideas of classic liberal thinkers proposes meaningful alternatives to understanding and using justice and equality – without result-oriented thinking, hidden normativity, and political appropriation.

McIntyre (1988) cautions that:

An analysis of the concepts of justice and rationality contends that unresolved fundamental conflicts exist in our society about what justice requires, because basic disagreement exists regarding what the rational justification is for acting one way rather than another. […] Thus, no such thing exists as a rationality that is not the rationality of some tradition. Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, and Hume are four major philosophers who represent rival traditions of inquiry. Each tradition developed within a particular historical context and sought to resolve particular conflicts. Allegiance to one tradition can allow for meaningful contact with other traditions in a way that can lead to understanding, vindication, or revision of that tradition in its continuing form. Thus, only by being grounded in the history of our own and opposing traditions will we be able to restore rationality and intelligibility to our moral attitudes and commitments today.

Going back to the conceptions of justice and equality of classical liberalism is an exercise to enrich and make contemporary discourse better. It offers an alternative view that is neither result-oriented nor particularistic. It is based on liberty, private property, and voluntarism, as well as and guided by the principle of proportionality – which can be summarized by the folksy-ism: “You must not use a steam hammer to crack a nut, if a nutcracker would do (for the reference, see common law case R v Goldstein [1983] 1 WLR 151, 155).”

On Justice

Defining justice is a difficult task. Theories of justice are abundant. It seems that conceptions of justice are bound by culture, historicity, and most importantly, ethical preferences. While some define justice as the pre-established harmony of a society (Plato, Aristotle), others understand it as the product of Divine Command (Bible) or of Nature (Ancient China) or of Natural Law (Scholastics). Yet others take justice to be a human creation, for example either through despotism (Chinese Legalism) or mutual agreement (Rousseau). Then, there are conceptions in which justice only plays the role of a subordinate value, for example in Mill’s utilitarianism. There, justice is just the by-product of social utility-maximization (Fay 1996).

Theories of justice usually focus on distributive, retributive, and pragmatic issues:

- Theories of distributive justice need to answer three questions:

- What goods are to be distributed – e.g. wealth, power, opportunities, etc.?

- Between what entities are they to be distributed – e.g. present people, future people, past people, sentient beings, members of groups, objects, etc.?

- What is the proper distribution – e.g. equal by input, equal by output, equal by process, meritocratic, by property, by status, by need, or can justice even be distributed?

Typical issues in distributive justice are social justice, fairness, property rights, and welfare-maximization. Generally, distributive justice theorists do not answer the question of who has the right to enforce a favored distribution. On the other hand, theories of distributive justice do not necessarily favor a type of distribution. Rather, many of them merely observe and describe distribution patterns according to some conceptions of justice. Other yet observe how distribution changes, as individuals interact. There is also a subset of this group of theories, focusing on the re-distribution of justice. This subset asks how to remedy unjust distributions. This group of theories first tries to identify what an unjust distribution is and then resort to institutions of redistribution – as organizations and/or as grammars of social interaction – tasked with redistribution.

- Theories of retributive justice are concerned with punishment for wrongdoing, and need to answer three questions:

- Why punish?

- Who should be punished?

- What punishment should wrongdoers receive?

Utilitarian theories look at the future consequences of punishment. Some often claim that strict punishment is just because it brings disincentives to wrongdoing. Others claim that lenient punishment is just because it reinforces inclusive social values. Then, there are retributive theories that look back to particular acts of wrongdoing, and attempt to balance them with deserved punishment. Some theories belonging to the redistributionist subgroup attempt arguing for redistribution based on retributive justice, i.e. if a good is unjustly distributed, the unjust distribution is a wrongdoing which must be retributed by redistribution.

- Pragmatic theories of justice are concerned with the application of justice.

For example, which institutions guarantee justice, who is in charge of observing what is unjust, what is the relationship between justice and law, or, which theories of sentencing are there? Pragmatic theories of justice are also interested in the evolution of the conception of justice.

The Complexity of Justice

The uses of the word “justice” criticized in this essay as well as the classic liberal theories discussed in its remainder belong to the first group, distributive justice. Note, again, that this does not by necessity entail a normative desideratum of how justice ought to be distributed – let alone a distribution of justice by organizations of distribution. It merely treats justice as a good and asks how this good is factually encountered or exchanged in a community or society. John Locke (1632 – 1704) claiming justice to be a propriety of the natural rights of humans and Buchanan & Mathieu postulating justice as an entitlement belong both to the group of distributive justice, even if they want justice to do different things.

The problem is not the concept, but the conception, i.e. the set of ideas standing behind the terms. In the past 50 years, the framework of reference for both changed radically. These concepts were appropriated by a specific political normativity.

Note furthermore that all conceptions of justice are based upon assumptions. Some assumptions seem relatively easy to accept, for example the existence of things, the reality of human behavior, or the group-orientation of this behavior. However, many other assumptions prove much more difficult to defend, for example, objective social desiderata, transitive valuation of desiderata and utility, context-independence of justice, or social independence of justice. The problem with most of the difficult and with some of the easy assumptions is that they fail at the individual. They fail to conceptualize justice as something that underlies subjective valuation. While most distributive theories of justice accept that justice is a good, not all of them do conceive this good as something that could have different values depending on its scarcity, context, or the preferences of the individuals involved in the distribution of the good. Instead, most theories of distributive justice imagine justice as a context-independent objective value – a value that can be asserted either by the community, by the society, by experts, or by organizations (Primeaux et al 2003, Sandel 1998).

What does justice being a matter of individual and subjective valuation mean? Firstly, it entails that justice is dependent on the individuals involved in the distribution and exchange of justice. Secondly, it says that the value judgement of those involved will vary from individual to individual, but also from context to context.

For example, Aðaldís is the owner of a bakery in Northern Iceland; without explaining or advertising for it, she lets everyone, customer or not, use the bakery’s toilet. Regina is a first-time customer. She wants to use the washroom but thinks it improper to do so without consuming, so she orders a cup of coffee. Ada is not a customer either; she enters the bakery and uses the toilet without buying anything. If there is no further exchange between them, everyone seems to accept the situation – tacitly – as just.

But imagine a different context: here Regina complains that she feels treated badly, because, to use the washrooms, she felt compelled at buying coffee. Also, Aðaldís might feel unjustly treated by Ada. And if any of them signal their feelings to Ada, even Ada might judge having been treated unjustly, because there were no signs of the obligation to consume in order to use the toilet prior to its use; or she might feel entitled to using the washroom and perceives therefore any attempt of preventing her from doing so as unjust. In this example, however, the three have possibilities of dealing with their individual judgements of justice. These possibilities entail exchange; for example, the exchange of money, the exchange of information, and the exchange of rules.

As far as the first is concerned, Aðaldís could set a fee for using the toilet. In the second case, she could put up a sign telling the rules of washroom-use. If she does not, she thinks that non-customers using the toilet is just, or she is just indifferent to it. But Ada and Regina alike could engage in the exchange of money and information. Ada could try to reason with either Aðaldís and / or Regina. If either makes a case and the others accept it, who is to say that the solution is unjust? In any case, there are different ways of dealing with the situation and the different, maybe divergent judgements of what is unjust. But what if no conclusion is reached? What if Ada, for example, still feels treated unjustly? What if Aðaldís wants to treat Ada and Regina differently, which leads Regina to feel unjustly treated?

While the appreciation of justice is dependent on context and individual valuation, the remedies against its distributions that are perceived as unjust are not. There are institutions – grammars of social interactions – that at the same time enable different valuations of justice and ward off incursions into an individual’s valuation, if that individual has an ultimately legitimate claim to ward off the incursion. The individual with the legitimate claim in the sense of the grammar of social interactions will be better equipped to implement its valuation of justice, trumping others while doing so.

While some define justice as the pre-established harmony of a society (Plato, Aristotle), others understand it as the product of Divine Command (Bible) or of Nature (Ancient China) or of Natural Law (Scholastics). Yet others take justice to be a human creation, for example either through despotism (Chinese Legalism) or mutual agreement (Rousseau). Then, there are conceptions in which justice only plays the role of a subordinate value, for example in Mill’s utilitarianism. There, justice is just the by-product of social utility-maximization.

In the example above: Aðaldís could resort to her property rights to impose her view on justice. It could either be letting everyone use the toilet or not, charging for the use of the washroom or not, differentiating between who can use, or even banning Regina from the bakery for complaining. Because of Aðaldís’ legitimate claim to private property, one of the main aspects of the grammar for social interaction, her subjective valuation of justice can prevail, albeit only in the context of her bakery. This does not mean that the other two individuals will accept Aðaldís’ decision as just. Perhaps they will do so; but due to the context they at least have to accept the hostess’ legitimate claim to the grammar of social interaction. Despite their individual valuation of the situation, they can react to the prevailing view, for example by seeking other bakeries or by turning into regulars. Finally, as context changes, valuations change. Maybe a massive inflow of tourists leads the baker to reconsider her position.

This example shows that the ensemble of individual valuation, discourse, exchange and claims basing on the grammar of social interaction makes the situation justice-apt. The valuation of justice is subjective, but the exchange of it is intersubjective. While the valuation is context dependent, the exchange relies on the grammar of social interaction, which, in turns, takes the context into account.

Virtues and Justice

Justice being a subjectively valued good does not entail absolute relativism, as far as classical liberalism is concerned. Instead of focusing on inputs, processes, and outputs – these being all a matter for subjective valuation and intersubjective transactionalism –, classical liberalism pivots on the moral character of the individual. After all, it is the individual that seeks justice and therefore wants to act justly, at least in a given context. Most importantly, this vision of justice captures an important intuition and institution: (Some) Individuals just want to do the “right thing”. The “right thing” depends on the individual’s circumstances, possibilities, and judgement. Since it will be the individual’s character guiding the person through these situations, according to many conceptions of classical liberalism, justice is a subjectively valued good but also a virtue of the individual.

There is no confusion in the double use of the same term. While justice, as a good, is the result of a context-sensitive subjective valuation by the individual, that individual can make that judgement on the basis of the virtue of justice. It is the strength of an individual’s character that allows for the subjective valuation of the justice of a given situation.

Virtues are the traits or strengths of character of individuals. (Vices, on the other hand, are the weaknesses of character). A virtue is a disposition, well entrenched in its possessor – something that “goes all the way down”, unlike a habit – to notice, expect, value, feel, desire, choose, act, and react in certain characteristic ways. To possess a virtue is to be a certain sort of person with a certain complex mindset. Possessing a virtue is a matter of degree. To possess such a disposition fully is to possess full or perfect virtue, which is rare, and there are several ways of falling short of this ideal. Most people who can be described as virtuous, and certainly markedly better than those who can truly be described as dishonest, self-centered and greedy, still have their blind spots – little areas where they do not act for the reasons one would expect. So, someone honest or kind in most situations, and notably so in demanding ones, may nevertheless be trivially tainted by snobbery, inclined to be disingenuous about their forebears and less than kind to strangers with the wrong accent.

Practical wisdom goes hand in hand with virtue. It is the individual’s capability of recognizing the context in which to act and which virtue to privilege. Generally, given that good intentions are intentions to act well or “do the right thing”, practical wisdom is the knowledge or understanding that enables its possessor to do just that, in a (or any) given situation (for a more complete discussion of virtue ethics, virtues, and practical wisdom, refer to Snow (2010) and (2015)).

Justice was already considered a virtue by Adam Smith (1723 – 1790). The author of The Wealth of Nations as well as The Theory of Moral Sentiments can be read as a virtue-ethicist (see Schneider (2018, forthcoming), McCloskey (2006), and Griswold (1999)). In fact, in both books and in the collection of essays and lectures later named The Theory of Jurisprudence, Smith stresses five virtues, which he understands as strengths of character: love, courage, temperance, justice, and self-interested prudence (which are different from the medieval set, the Cardinal and the Christian virtues: Prudence, Justice, Fortitude or Courage, Temperance, and Faith, Hope, Love).

In Smith’s work, justice is not a social desideratum neither is it an objective outcome. It is the capability of the individual to “do the right thing” in each context and under particular constraints. In fact, whether someone acts justly, or not, is something that can only be assessed in terms of introspection and of inter-subjective scrutiny. For Smith, there is no distribution, institution, institute, process, or outcome that is just or leads to justice (as an abstract term or theory). Justice is the strength of character of the individual and it is the individual that acts justly in given situations. Smith contends that there is a long-termed convergence of the individuals’ abstract notion of justice in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). There, his theory of the impartial observer asserts some form of ethical convergence of virtues. But as the application of virtue to a specific circumstance is, as the observer is, too, a matter for the individual, there is only the long-term convergence because of actions by the individuals.

Adam Smith on Justice

In The Wealth of Nations, Smith defines natural liberty using justice (1776, 311):

“Every man, as long as he does not violate the laws of justice, is left perfectly free to pursue his own interest his own way, and to bring both his industry and capital into competition with those of any other man”.

A not careful reading could suggest, here, that Smith is thinking about a justice rulebook. But in other passages of The Wealth of Nations, he makes it clear that justice is an infinite set of permissible actions that depend only on the agent. It does not mean that the induvial is free to do anything and rationalize actions as just. But it means that it is the individual that judges which virtue to apply, and how to apply it. It is the individual that values justice in a specific context and given the different courses of action to take. Justice, for Smith, is also the individual’s commitment to the negative of his proposition on injustice, which states that improperly motivated (that is, intentionally) hurtful actions alone deserve punishment because they are the objects of a widely shared sense of resentment.

By the way, The Wealth of Nations reserves a whole book to jurisprudence – which Adam Smith confusingly calls justice, or the administration of justice – in which the improperly motivated actions are treated. In this book, he makes it clear, again, that despite the individual valuation of justice – or the failure in doing so – there are instruments like the grammar of social exchanges, that lie outside the scope of virtue to give way to a person’s legitimate claims, especially private property.

Smith sees society as seeking human socio-economic betterment through the control of actions that common experience leads to judge as hurtful rather than through collective actions designed to achieve future conjectured benefits. The latter is uncertain and fraught with unintended consequences; moreover, to his appreciation, history is full of examples of grandiose failures in the name of objective desiderata disguised as justice. The former relies on natural impulses for individuals and assemblies to pursue betterment, risking only their own resources; this framework led him to oppose slavery, colonialism, empire, mercantilism, and taxation without representation at a time when such views were unpopular.

In Smith’s work, justice is not a social desideratum neither is it an objective outcome. It is the capability of the individual to “do the right thing” in each context and under particular constraints.

Also – and as every virtue-ethicist – in Smith’s thought, the individual never acts on one virtue alone. The virtuous individual knows how to combine all the strengths of character to address the specific situation. Smith’s analogy of writing, and his use of it to contrast justice with the rest of the virtues, is one of the most important parts of The Theory of Moral Sentiments. He considers how precision and vagueness, clear rules and ambiguous ideals, both have important roles to play in moral judgment (1759, 3, VI,11):

The rules of justice may be compared to the rules of grammar; the rules of the other virtues, to the rules which critics lay down for the attainment of what is sublime and elegant in composition. The one, are precise, accurate, and indispensable. The other, are loose, vague, and indeterminate, and present us rather with a general idea of the perfection we ought to aim at, than afford us any certain and infallible directions for acquiring it. A man may learn to write grammatically by rule, with the most absolute infallibility; and so, perhaps, he may be taught to act justly. But there are no rules whose observance will infallibly lead us to the attainment of elegance or sublimity in writing; though there are some which may help us, in some measure, to correct and ascertain the vague ideas which we might otherwise have entertained of those perfections. And there are no rules by the knowledge of which we can infallibly be taught to act upon all occasions with prudence, with just magnanimity, or proper beneficence: though there are some which may enable us to correct and ascertain, in several respects, the imperfect ideas which we might otherwise have entertained of those virtues.

Adam Smith’s and the classic-liberal approach to justice is in many ways less problematic than the contemporary discourse. It is less bound by unrealistic assumptions such as an ultimate objectivity of justice, or the organizational administration of the redistribution of justice. Considering justice as a good underlying subjective valuation and as a strength of character of the agent captures important notions of how individuals act without prejudging outcomes. On the other hand, it burdens individuals with responsibility. If justice is a strength of character, every individual becomes challenged by the own idea of justice in action and is therefore held accountable in every single action. In this view, justice cannot be outsourced to society, to organizations, or to government; justice is an immediate value and motivator of the individual in action.

On Equality

This second term employed with seductive euphoria in the contemporary discourse is no less of a problem than the first. Equality, too, underwent some changes in its meaning over time. While it long ago meant equal obligation to follow the social desiderata pre-determined by nature and unveiled by the Logos (Ancient Greece), it was also understood as an isonomy of power relations among chieftains (Scotland, Iceland), clans (Mongols), aristocrats (most European monarchies and city-states) or as an equal subordination under a monarch (Qin and Tang China). Equality could furthermore be understood as an equitable value of human life (Hebrew Bible) (Siedentop 2014).

At the latest in 16th century Europe, the idea that all people – at least all men – were created equal and therefore had equal claims to political rights became widespread. There was, however, considerable discussion about the implication of the claim. One of the most intrepid theorists of equality was the classical liberal John Locke. To his mind, equality is a property of the human being and the basis of the individual’s political and judiical rights – and namely it is not an adjective to outcomes, disparities, or processes (Waldron 2002).

Justice burdens individuals with responsibility. If justice is a strength of character, every individual becomes challenged by the own idea of justice in action and is therefore held accountable in every single action. In this view, justice cannot be outsourced to society, to organizations, or to government; justice is an immediate value and motivator of the individual in action.